Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Glutathione is a remarkably functional molecule with diverse features, which include being an antioxidant, a regulator of DNA synthesis and repair, a protector of thiol groups in proteins, a stabilizer of cell membranes, and a detoxifier of xenobiotics. Glutathione exists in two states-oxidized and reduced. Under normal physiological conditions of cellular homeostasis, glutathione remains primarily in its reduced form.

- glutathione

- brain

- aging

1. Introduction

Glutathione (GSH) is a tripeptide that contains cysteine, glutamic acid, and glycine residues, which are distributed ubiquitously in every cell [1]. It serves as an endogenous antioxidant that affects many cellular functions. GSH and several enzymes combine to form the glutathione system, which plays a crucial role in the utilization and regulation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS, respectively) in organisms. Intracellular levels of GSH are maintained by direct uptake of exogenous GSH, de novo GSH synthesis, and GSH redox cycling. De novo synthesis of GSH from cysteine and glutamic acid involves catalysis by glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCL) to form gamma-glutamyl cysteine (g-GC) and the subsequent addition of glycine to g-GC by glutathione synthase (GS) [2]. During the process of GSH redox cycling, the enzyme glutathione peroxidase (GPx) oxidizes GSH to glutathione disulfide (GSSG) during detoxification of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or other organic hydroperoxides. The oxidized form, GSSG, can be converted back to GSH by glutathione reductase (GR). Conjugation of GSH by the enzyme glutathione S-transferase (GST) to xenobiotic compounds yields nontoxic products, thereby effecting their detoxification [3][4].

2. A Pivotal Role for GSH in the Regulation of Homeostasis and Metabolism in the Nervous System

During the aging process, GSH plays a vital role in neuronal defense against damage caused by oxidants like ROS and RNS. Various neurodegenerative disorders are characterized by the depletion of cellular GSH, probably due to its counteracting oxidative stress and calcium ion (Ca2+) imbalance [5]. There is marked heterogeneity in the cellular distribution of GSH in the CNS neurons of adult rats, gerbils, and rabbits. The non-neuronal elements of the CNS and the peripheral nervous system (PNS), namely the glia, ependyma, and endothelia, exhibit high levels of GSH not found in the neuronal cell bodies or granule cells. GSTs are also likely to be heterogeneously distributed in the CNS. For example, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes express µ-GST and n-GST, respectively, while pial, ependymal, and vascular elements express various quantities of both µ- and n-GST. Alpha-GST is present in both neurons and non-neuronal elements of the nervous system. The developing nervous system is exposed to various xenobiotics through the placental circulation and undergoes a dramatic change in the oxygen environment at birth [6]. Therefore, the GSH system plays an important role in the regulation of redox homeostasis and protects newborns against the hyperoxic extrauterine environment.

Mitochondria are an important source of ROS and RNS. Roughly 10 to 20% of GSH is contained in the mitochondria in neural cells and most other tissues [7]. The mitochondrial compartment contains more GSH than any other cellular compartment, yet the mitochondria do not contain the enzymes necessary for its biosynthesis [8]. Instead, mitochondria import GSH from the cytosol effectively using specific GSH transport systems [9]. The exact system used in each case depends on the substrate and the tissue. For example, the import of GSH into kidney and liver mitochondria can occur primarily using 2-oxoglutarate (2-OG; SLC25A11) or dicarboxylate (DIC; SLC25A10) as a carrier, while tricarboxylate (TTC, SLC25A1) serves as a carrier in CNS neurons and astrocytes. The 2-OG carrier (OGC) mediates the exchange of cytosolic GSH and mitochondrial dicarboxylates, including 2-OG [9].

The tripeptide structure of GSH suggest its potential role as a neuroactive molecule. All three of its amino acid residues can interfere with neuronal signaling through glutamate (Glu) receptors. Loss or improper function of Glu receptors or alteration of cerebral GSH levels can lead to neuropsychiatric symptoms or neurological abnormalities. The conformational flexibility of GSH allows for its binding to all classes of Glu receptors via its glutamyl residue due to its similarity to the natural receptor agonist, L-glutamate. The cysteine residue in GSH has neurotoxic properties in its free state, although it is not toxic in peptide form. At low concentrations, GSH is neuroprotective, but at high (millimolar; mM) concentrations, GSH may affect the redox state of glutamate receptors via its free thiol group. Similar to free glycine, the glycine residue in GSH serves as a co-agonist of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor and as the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the spinal cord [10][11]. Alterations in NMDA receptor function can alter the calcium signaling cascade and affect synaptic plasticity, leading to pathophysiological changes in the CNS.

The redox potential regulates the activity of the NMDA receptor, which normally fluctuates between fully oxidized and fully reduced states [12][13][14][15]. Redox homeostasis in the brain is very important, as the consumption of high levels of oxygen produces many harmful free radicals, including superoxide anions (O2•−), hydroxyl radicals (•OH), lipoperoxide radicals (LOO·), nitric oxide radicals (NO•), and nitrogen dioxide radicals (NO2•) [16][17]. As an antioxidant, the GSH system maintains thiols by the scavenging of free radicals and by reversible thiol-disulfide exchange reactions. Therefore, it is a putative endogenous redox modulator of the NMDA receptor activity [12][13][14][15].

Mitochondrial GSH serves as a natural antioxidant store. Selective depletion of mitochondrial but not cytoplasmic GSH from cerebellar granule neurons (CGNs) is associated with enhanced permeability of mitochondrial transition pores, increased ROS production, and increased cell death. Interestingly, different cell types in the CNS exhibit varied sensitivity to oxidative stress due to their differing levels of mitochondrial GSH [18]. For example, astrocytes are more vulnerable to oxidative and nitrosative stress than cells with higher levels of GSH [18]. Although the human brain constitutes only 2% of the total body weight, it utilizes 20% of the oxygen consumed by the body. Neurons support high levels of oxidative phosphorylation, which is expected to generate a large amount of ROS. Cells that generate such high levels of ROS require an antioxidative defense system to protect cellular structures from ROS damage [19][20]. In brain cells, the antioxidant function of GSH plays a key role in their defense against oxidative stress.

Depletion of this cellular reservoir of GSH leads to the amplification of oxidative and nitrosative cell damage, hypernitrosylation, increased levels of inflammation, disturbances in intracellular signaling pathways for p53, Janus kinases (JAK), and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB); decreased DNA synthesis and cell proliferation; activation of cytochrome c, inactivation of complex I of the electron transport chain and the apoptotic pathways; blockage of the methionine cycle; and compromised epigenetic regulation of gene expression. GSH depletion also has deleterious effects on redox homeostasis of the immune system, molecular pathways involved in oxidative and nitrosative stresses, control of energy production, and mitochondrial survival in different cell types [21]. GSH imbalance and/or deficiency in the neurons is involved in the pathogenesis of brain disorders, including AD, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), autism, bipolar disorder, Huntington’s disease (HD), multiple sclerosis (MS), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and schizophrenia [16]. Many neurological disorders are associated with impaired balance between ROS generation and activity of the antioxidant system, particularly GSH, as reviewed recently [22]. For example, impaired GSH metabolism contributes to PD pathogenesis. Abnormal mitochondrial functioning may also play a crucial role in these diseases [22].

Congenital GSH synthetase deficiency can cause mental retardation, spastic quadriplegia (also called spastic tetraparesis; a form of cerebral palsy), cerebellar dysfunction, and γ-glutamyl-cysteine synthetase deficiency, which can lead to spinocerebral degradation, ataxia, and the absence of lower-limb reflexes [23][24][25][26]. The concentration of GSH decreases in the substantia nigra, during both ontogenesis and in the degenerating dopaminergic neurons of PD patients [27][28][29][30]. GSH levels are reduced in the brains of epilepsy patients during convulsive seizures [31] and in genetically epileptic (tg/tg) transgenic mice [32]. Furthermore, the depletion of GSH in adult rats by treatment with buthionine sulfoximine leads to the development of seizures [33].

Thus, glutathione plays an important role in the onset and progression of neurological disorders and neurodegenerative diseases, and may serve as a biomarker for diagnostic screening for these disorders.

3. Glutathione Regulates Aging and Neurodegeneration

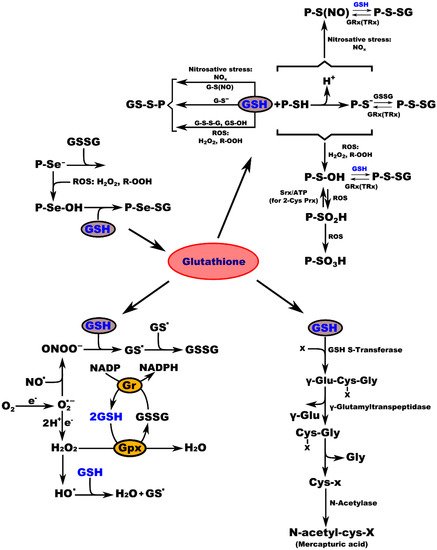

Biochemical studies of the effects of aging on the antioxidant systems highlighted the existence of age-related changes in the GSH content of the nervous system. Aging is often associated with impairments in CNS function, resulting from loss of neurons and leading to diminished cognitive performance. Free radicals, particularly oxygen radicals, play important roles in age-related changes and in the pathogenesis of several neurodegenerative diseases. Our defense against oxygen radicals relies on the enzymes of the glutathione/thioredoxin antioxidant system, which inactivate ROS and NOS, glutathione peroxidase detoxifies peroxides, including H2O2 and peroxides that are generated during the oxidation of membrane lipids. The enzymatic oxidation of GSH to the disulfide GSSG determines the extent of the reduction in the peroxide levels. To maintain the cellular balance of GSH and GSSG, GSH can be regenerated from GSSG by glutathione reductase with NADPH as a cofactor [9]. GSH provides approximately 90% of the non-protein sulfhydryl groups in the cells and maintains the thiol status of the cellular proteins (Figure 1) [34].

Figure 1. Interconnection of GSH metabolic pathways. P-protein; P-Se−-protein-selenate anion; ROS-reactive oxygen species; H2O2-hydrogen peroxide; R-OOH-hydroperoxide; P-Se-OH-protein-selenenic acid; GSH-glutathione, P-Se-SG-protein-selenate; NOx-reactive nitrogen species; G-S(NO)-S-nitroso-glutathione; G-S--glutathione-thiolate; GSSG-glutathione disulfide (oxidized glutathione); GS-OH--glutathione sulfenic acid; P-SH-protein sulfhydryl group; H+-proton; P-S−-protein-thiolate anion; P-S(NO)-protein-S-nitroso thiol; P-S-SG-protein-S-glutathione; GRx(TRx)-glutaredoxin (thioredoxin); P-S-OH-protein-sulfenic acid; Srx-sulfiredoxin; ATP-adenosine triphosphate; 2-Cys Prx-2-cysteine peroxiredoxin; P-SO2H-protein-sulfinic acid; P-SO3H-protein-sulfonic acid; O2-oxygen; O2.--superoxide radical; NO.-nitric oxide radical; ONOO−-peroxynitrite; GS.-glutathione radical; e−-electron; Gr-glutathione reductase; GPx-glutathione peroxidase; NADP-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NADPH-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; H2O-water; HO.-hydroxyl radical; x-compound with an electrophilic center that can be conjugated to GSH by glutathione S-transferase; γ-Glu-Cys-x-Gly-γ-glutamate-cysteine-x-glycine; γ-Glu-γ-glutamic acid; Cys-x-Gly-cysteine-x-glycine; Gly-glycine; Cys-x-cysteine-x; N-acetyl-cys-x-mercapturic acid-x.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/molecules27010324

References

- Noctor, G.; Queval, G.; Mhamdi, A.; Chaouch, S.; Foyer, C.H. Glutathione. Arab. Book 2011, 9, e0142.

- Lian, G.; Gnanaprakasam, J.R.; Wang, T.; Wu, R.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Shen, Y.; Yang, M.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; et al. Glutathione de novo synthesis but not recycling process coordinates with glutamine catabolism to control redox homeostasis and directs murine T cell differentiation. eLife 2018, 7, e36158.

- Circu, M.L.; Aw, T.Y. Glutathione and apoptosis. Free Radic. Res. 2008, 42, 689–706.

- Lushchak, V.I. Glutathione Homeostasis and Functions: Potential Targets for Medical Interventions. J. Amino Acids 2012, 2012, 736837.

- Belrose, J.C.; Xie, Y.F.; Gierszewski, L.J.; MacDonald, J.F.; Jackson, M.F. Loss of glutathione homeostasis associated with neuronal senescence facilitates TRPM2 channel activation in cultured hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Mol. Brain 2012, 5, 11.

- Beiswanger, C.M.; Diegmann, M.H.; Novak, R.F.; Philbert, M.A.; Graessle, T.L.; Reuhl, K.R.; Lowndes, H.E. Developmental changes in the cellular distribution of glutathione and glutathione S-transferases in the murine nervous system. Neurotoxicology 1995, 16, 425–440.

- Huang, J.; Philbert, M.A. Distribution of glutathione and glutathione-related enzyme systems in mitochondria and cytosol of cultured cerebellar astrocytes and granule cells. Brain Res. 1995, 680, 16–22.

- Griffith, O.W.; Meister, A. Origin and turnover of mitochondrial glutathione. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1985, 82, 4668–4672.

- Ribas, V.; García-Ruiz, C.; Fernández-Checa, J.C. Glutathione and mitochondria. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 151.

- Oja, S.S.; Janáky, R.; Varga, V.; Saransaari, P. Modulation of glutamate receptor functions by glutathione. Neurochem. Int. 2000, 37, 299–306.

- Shen, X.M.; Dryhurst, G. Oxidation chemistry of (−)-norepinephrine in the presence of L-cysteine. J. Med. Chem. 1996, 39, 2018–2029.

- Aizenman, E.; Lipton, S.A.; Loring, R.H. Selective modulation of NMDA responses by reduction and oxidation. Neuron 1989, 2, 1257–1263.

- Choi, Y.B.; Lipton, S.A. Redox modulation of the NMDA receptor. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2000, 57, 1535–1541.

- Gozlan, H.; Ben-Ari, Y. NMDA receptor redox sites: Are they targets for selective neuronal protection? Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1995, 16, 368–374.

- Sullivan, J.M.; Traynelis, S.F.; Chen, H.S.; Escobar, W.; Heinemann, S.F.; Lipton, S.A. Identification of two cysteine residues that are required for redox modulation of the NMDA subtype of glutamate receptor. Neuron 1994, 13, 929–936.

- Gu, F.; Chauhan, V.; Chauhan, A. Glutathione redox imbalance in brain disorders. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2015, 18, 89–95.

- Phaniendra, A.; Jestadi, D.B.; Periyasamy, L. Free radicals: Properties, sources, targets, and their implication in various diseases. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2015, 30, 11–26.

- Wilkins, H.M.; Kirchhof, D.; Manning, E.; Joseph, J.W.; Linseman, D.A. Mitochondrial glutathione transport is a key determinant of neuronal susceptibility to oxidative and nitrosative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 5091–5101.

- Dringen, R.; Hirrlinger, J. Glutathione pathways in the brain. Biol. Chem. 2003, 384, 505–516.

- Iskusnykh, I.Y.; Popova, T.N.; Agarkov, A.A.; Pinheiro de Carvalho, M.; Rjevskiy, S.G. Expression of Glutathione Peroxidase and Glutathione Reductase and Level of Free Radical Processes under Toxic Hepatitis in Rats. J. Toxicol. 2013, 2013, 870628.

- Morris, G.; Anderson, G.; Dean, O.; Berk, M.; Galecki, P.; Martin-Subero, M.; Maes, M. The glutathione system: A new drug target in neuroimmune disorders. Mol. Neurobiol. 2014, 50, 1059–1084.

- Dringen, R.; Gutterer, J.M.; Hirrlinger, J. Glutathione metabolism in brain metabolic interaction between astrocytes and neurons in the defense against reactive oxygen species. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000, 267, 4912–4916.

- Njålsson, R. Glutathione synthetase deficiency. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005, 62, 1938–1945.

- Njålsson, R.; Ristoff, E.; Carlsson, K.; Winkler, A.; Larsson, A.; Norgren, S. Genotype, enzyme activity, glutathione level, and clinical phenotype in patients with glutathione synthetase deficiency. Hum. Genet. 2005, 116, 384–389.

- Ristoff, E.; Larsson, A. Inborn errors in the metabolism of glutathione. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2007, 2, 16.

- Ristoff, E.; Mayatepek, E.; Larsson, A. Long-term clinical outcome in patients with glutathione synthetase deficiency. J. Pediatr. 2001, 139, 79–84.

- Bannon, M.J.; Goedert, M.; Williams, B. The possible relation of glutathione, melanin and 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) to Parkinson’s disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1984, 33, 2697–2698.

- Perry, T.L.; Yong, V.W. Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, progressive supranuclear palsy and glutathione metabolism in the substantia nigra of patients. Neurosci. Lett. 1986, 67, 269–274.

- Riederer, P.; Sofic, E.; Rausch, W.D.; Schmidt, B.; Reynolds, G.P.; Jellinger, K.; Youdim, M.B. Transition metals, ferritin, glutathione, and ascorbic acid in parkinsonian brains. J. Neurochem. 1989, 52, 515–520.

- Smeyne, M.; Smeyne, R.J. Glutathione metabolism and Parkinson’s disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 62, 13–25.

- Mueller, S.G.; Trabesinger, A.H.; Boesiger, P.; Wieser, H.G. Brain glutathione levels in patients with epilepsy measured by in vivo (1)H-MRS. Neurology 2001, 57, 1422–1427.

- Abbott, L.C.; Nejad, H.H.; Bottje, W.G.; Hassan, A.S. Glutathione levels in specific brain regions of genetically epileptic (tg/tg) mice. Brain Res. Bull. 1990, 25, 629–631.

- Hu, H.L.; Bennett, N.; Holton, J.L.; Nolan, C.C.; Lister, T.; Cavanagh, J.B.; Ray, D.E. Glutathione depletion increases brain susceptibility to m-dinitrobenzene neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicology 1999, 20, 83–90.

- Ravindranath, V.; Shivakumar, B.R.; Anandatheerthavarada, H.K. Low glutathione levels in brain regions of aged rats. Neurosci. Lett. 1989, 101, 187–190.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!