Industrial and service development has led researchers to focus on non-conventional materials with significant roles in innovation development and implementation. Entrepreneurs aim to develop innovative and creative strategies using good, valuable, durable, and sustainable materials that serve industrial and economic development. As result, the use of natural construction and production materials has increased interest related to the desire of developing greener and/or environmentally friendly processes. Several natural, re-emerging materials used in the past (e.g., bamboo, straw, reeds, and hemp) have been found useful again and deserving of research to fully understand their potential for different applications.

- bamboo

- materials

- mechanical properties

- mechanical engineering

- climate

- Industry 4.0

- innovation

- energy

1. Introduction

2. Innovative Industrial Use of Bamboo

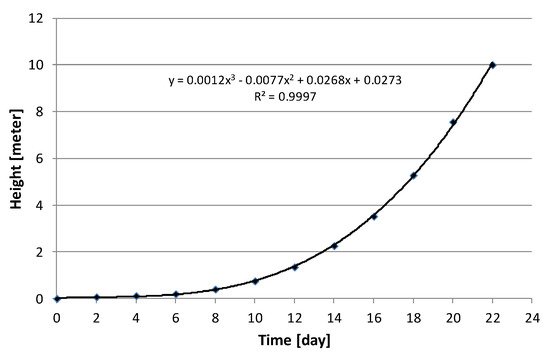

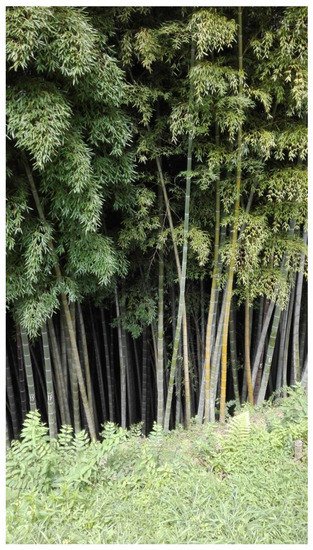

2.1. Bamboo Plant Characteristics

2.2. Current Bamboo Applications

2.3. Bamboo for Environmental Protection

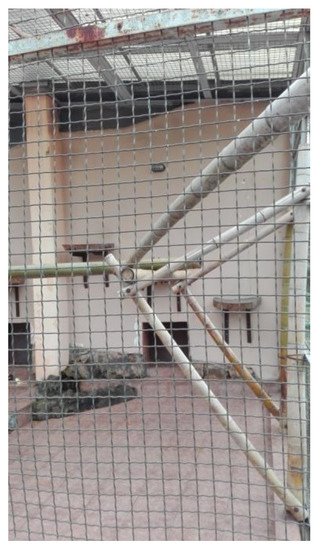

2.4. Bamboo as Material in the Construction Sector

| Properties [kN/cm2] | Spruce Wood | Steel | Bamboo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modulus of elasticity | 1100 | 21,000 | 2000 |

| Modulus of rupture | 7.2 | 20.0 | 12.1–20.9 |

| Compressive strength | 4.3 | 14.0 | 6.2–9.5 |

| Tension strength | 8.9 | 16.0 | 14.8–38.4 |

| Bending strength | 6.8 | 14.0 | 7.6–27.6 |

| Shear strength | 0.7 | 9.2 | 2.0 |

2.5. Bamboo for Energy Production

2.6. Bamboo as an Additive for Biodegradable Products

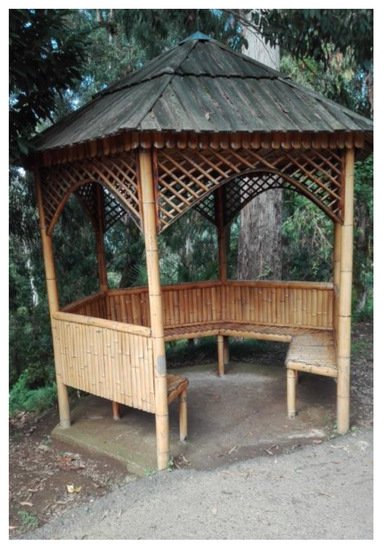

2.7. Bamboo in Gardening and Architecture

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su14041955

References

- Javadian, A.; Smith, I.F.C.; Saeidi, N.; Hebel, D.E. Mechanical Properties of Bamboo through Measurement of Culm Physical Properties for Composite Fabrication of Structural Concrete Reinforcement. Front. Mater. 2019, 6, 1–18.

- Shen, L.; Yang, J.; Zhang, R.; Shao, C.; Song, X. The benefits and barriers for promoting bamboo as a green building material in China—An integrative analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2493.

- Chaowana, K.; Wisadsatorn, S.; Chaowana, P. Bamboo as a Sustainable Building Material—Culm Characteristics and Properties. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7376.

- Bąkowska, K.; Marczewski, K.; Sawulski, J.; Sztolsztejner, A. Rola Gospodarki Kreatywnej w Polsce; Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny: Warsaw, Poland, 2020.

- Wu, S.H.; Fan, K.K. Sustainable development of traditional bamboo ferniture in Taiwan: A study on design style. J. Sci. Des. 2021, 5, 2_51–2_60.

- Rao, F.; Ji, Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yu, W. Outdoor bamboo-fiber-reinforced composite: Influence of resin content on water resistance and mechanical properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 261, 120022.

- Emamverdian, A.; Ding, Y.; Ranaei, F.; Ahmad, Z. Application of Bamboo Plants in Nine Aspects. Sci. World J. 2020, 2020, 7284203.

- Zhang, H.; Zhong, J.; Liu, Z.; Mai, J.; Liu, H.; Mai, X. Dyed bamboo composite materials with excellent anti-microbial corrosion. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2021, 4, 294–305.

- Colombo, L.A.; Pansera, M.; Owen, R. The discourse of eco-innovation in the European Union: An analysis of the Eco-Innovation Action Plan and Horizon 2020. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 653–665.

- Borowski, P.F. Innovation strategy on the example of companies using bamboo. J. Innov. Entrep. 2021, 10, 3.

- Kumar, A.; Behura, A.K.; Rajak, D.K.; Behera, A.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, R. Fundamental Concepts of Bamboo: Classifications, Properties and Applications. Bamboo Fiber Compos. 2021, 39–62.

- Gui, Y.; Wang, S.; Quan, L.; Zhou, C.; Long, S.; Zheng, H.; Jin, L.; Zhang, X.; Ma, N.; Fan, L. Genome size and sequence composition of moso bamboo: A comparative study. Sci. China Ser. C 2007, 50, 700–705.

- Shao, Z.; Huang, S.; Wu, F.; Zhou, L.; Clement, A. A study on the difference of structure and strength between internodes and nodes of bamboo. J. Bamboo Res. 2008, 27, 48–52.

- Chung, M.J.; Wang, S.Y. Physical and mechanical properties of composites made from bamboo and woody wastes in Taiwan. J. Wood Sci. 2019, 65, 1–10.

- Tamang, D.K.; Dhakal, D.; Shrestha, D.G. Bamboo resources of Sikkim Himalaya: Diversity, distribution and utilization. J. For. Res. 2014, 25, 929–934.

- Borowski, P. Bamboo as an innovative material for many branches of world industry. Ann. WULS SGGW For. Wood Technol. 2019, 107, 13–18.

- Liese, W. Research on bamboo. Wood Sci. Technol. 1987, 21, 189–209.

- Grosser, D.; Liese, W. On the anatomy of Asian bamboos, with special reference to their vascular bundles. Wood Sci. Technol. 1971, 5, 290–312.

- Bucur, V. Traditional and new materials for the reeds of woodwind musical instruments. Wood Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 1157–1187.

- Dixon, P.G.; Gibson, L.J. The structure and mechanics of Moso bamboo material. J. R. Soc. Interface 2014, 11, 20140321.

- Marsh, J.; Smith, N. New Bamboo Industries and Pro Poor Impacts: Lesions from China and Potential for Mekong Countries. 2012. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/010/ag131e/ag/131e25.htm (accessed on 6 January 2022).

- Atanda, J. Environmental impacts of bamboo as a substitute constructional material in Nigeria. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2015, 3, 33–39.

- Dai, Y.; Hwang, S.-H. Technique, Creativity, and Sustainability of Bamboo Craft Courses: Teaching Educational Practices for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2487.

- Lobovikov, M.; Paudel, S.; Piazza, M.; Ren, H.; Wu, J. World Bamboo Resources-A Thematic Study Prepared in the Framework of the Global Forest Resources Assessment 2005; Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2007; p. 33.

- Canavan, S.; Richardson, D.M.; Visser, V.; Le Roux, J.J.; Vorontsova, M.S.; Wilson, J.R. The global distribution of bamboos: Assessing correlates of introduction and invasion. AoB Plants 2017, 9, plw078.

- Du, H.; Mao, F.; Li, X.; Zhou, G.; Xu, X.; Han, N.; Sun, S.; Gao, G.; Cui, L.; Li, Y.; et al. Mapping global bamboo forest distribution using multisource remote sensing data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2018, 11, 1458–1471.

- Liu, W.; Hui, C.; Wang, F.; Wang, M.; Liu, G. Review of the resources and utilization of bamboo in China. Bamboo Curr. Future Prospects 2018, 133–142.

- Terefe, R.; Jian, L.; Kunyong, Y. Role of bamboo forest for mitigation and adaptation to climate change challenges in China. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 2019, 24, 1–7.

- Yasin, I.; Priyanto, A. Analysis of bamboo mechanical properties as construction eco-friendly materials to minimizing global warming effect. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 535, 012001.

- Kang, F.; Li, X.; Du, H.; Mao, F.; Zhou, G.; Xu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Ji, J.; Wang, J. Spatiotemporal Evolution of the Carbon Fluxes from Bamboo Forests and their Response to Climate Change Based on a BEPS Model in China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 366.

- Guo, Z.; Hu, H.; Li, P.; Li, N.; Fang, J. Spatio-temporal changes in biomass carbon sinks in China’s forests from 1977 to 2008. Sci. China Life Sci. 2013, 56, 661–671.

- Xu, B.; Guo, Z.; Piao, S.; Fang, J. Biomass carbon stocks in China’s forests between 2000 and 2050: A prediction based on forest biomass-age relationships. Sci. China Life Sci. 2010, 53, 776–783.

- Laidler, K. The Bear’s Necessity. 2003. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2003/mar/20/research.science (accessed on 6 January 2022).

- Available online: https://bamcore.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Carbon-Farming-with-Timber-Bamboo.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2022).

- Ban, Y.; Zhi, W.; Fei, M.; Liu, W.; Yu, D.; Fu, T.; Qiu, R. Preparation and Performance of Cement Mortar Reinforced by Modified Bamboo Fibers. Polymers 2020, 12, 2650.

- Frías-Rojas, M.; Sánchez-de-Rojas-Gómez, M.I.; Medina-Martínez, C.; Villar-Cociña, E. New Trends for Nonconventional Cement-Based Materials: Industrial and Agricultural Waste. In Sustainable and Nonconventional Construction Materials Using Inorganic Bonded Fiber Composites; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2017; pp. 165–183.

- Gutu, T.A. Study on the mechanical strength properties of bamboo to enhance its diversification on its utilization. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2013, 2, 314–319.

- Available online: https://www.azom.com/properties.aspx?ArticleID=965 (accessed on 6 January 2022).

- Mousavi, S.R.; Zamani, M.H.; Estaji, S.; Tayouri, M.I.; Arjmand, M.; Jafari, S.H.; Nouranian, S.; Khonakdar, H.A. Mechanical properties of bamboo fiber-reinforced polymer composites: A review of recent case studies. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 3143–3167.

- Shu, B.; Xiao, Z.; Hong, L.; Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Fu, N.; Lu, X. Review on the application of bamboo-based materials in construction engineering. J. Renew. Mater. 2020, 8, 1215–1242.

- Mahamat, A.; Bih, N.L.; Ayeni, O.; Onwualu, P.A.; Savastano, H., Jr.; Soboyejo, W.O. Development of Sustainable and Eco-Friendly Materials from Termite Hill Soil Stabilized with Cement for Low-Cost Housing in Chad. Buildings 2021, 11, 86.

- Available online: https://www.fpl.fs.fed.us/documnts/fplgtr/fplgtr113/ch04.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2022).

- Chandrasekaran, V. Characteristics investigations of dry bamboo ash fractional replaced cement with in M25 grade concrete. Ann. Chim. Sci. Matér. 2021, 45, 153–159.

- Onikeku, O.; Shitote, S.M.; Mwero, J.; Adedeji, A. Evaluation of characteristics of concrete mixed with bamboo leaf ash. Open Constr. Build. Technol. J. 2019, 13, 67–80.

- Li, Z.; Chen, C.; Mi, R.; Gan, W.; Dai, J.; Jiao, M.; Xie, H.; Yao, Y.; Xiao, S.; Hu, L. A strong, tough, and scalable structural material from fast-growing bamboo. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1906308.

- Le, T.M.A.; Truong, H. Overview of Bamboo Biomass for Energy Production. 2014. Available online: https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:hal:wpaper:halshs-01100209 (accessed on 6 January 2022).

- Schneider, D.; Escala, M.; Supawittayayothin, K.; Tippayawong, N. Characterization of biochar from hydrothermal carbonization of bamboo. Int. J. Energy Environ. 2011, 2, 647–652.

- Daňo, M.; Viglašová, E.; Galamboš, M.; Štamberg, K.; Kujan, J. Surface Complexation Models of Pertechnetate on Biochar/Montmorillonite Composite—Batch and Dynamic Sorption Study. Materials 2020, 13, 3108.

- Zhang, X.; Sarmah, A.; Bolan, N.; He, L.; Lin, X.; Che, L.; Tang, C.; Wang, H. Effect of aging process on adsorption of diethyl phthalate in soils amended with bamboo biochar. Chemosphere 2016, 142, 28–34.

- Żelaziński, T.; Ekielski, A.; Tulska, E.; Vladut, V.; Durczak, K. Wood Dust Application for Improvement of Selected Properties of Thermoplastic Starch. Inmatech Agric. Eng. 2019, 58, 37–43.

- Zhao, D.X.; Cai, X.; Shou, G.Z.; Gu, Y.Q.; Wang, P.X. Study on the Preparation of Bamboo Plastic Composite Intend for Additive Manufacturing. In Key Engineering Materials; Wang, G., Wang, H., Zhang, X., Li, Y., Li, C., Li, Y., Eds.; Trans Tech Publications Ltd.: Freienbach, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 667, pp. 250–258.

- Khalil, H.A.; Mohamad, H.C.C.; Khairunnisa, A.R.; Owolabi, F.A.T.; Asniza, M.; Rizal, S.; Fazita, M.R.N.; Paridah, M.T.; Mustapha, A.; Tahir, P.M. Development and characterization of bamboo fiber reinforced biopolymer films. Mater. Res. Express 2018, 5, 085309.

- Junior, A.E.C.; Baretto, A.C.H.; Rossa, D.S.; Maia, F.J.N.; Lomanaco, D.; Mazzetto, S.E. Thermal and mechanical properties of biocomposites based on a cashew nut shell liquid matrix reinforced with bamboo fibers. J. Compos. Mater. 2015, 49, 2203–2215.

- Devi, S.Y.; Indran, S.; Divya, D. Futuristic Prospects of Bamboo Fiber in Textile and Apparel Industries: Fabrication and Characterization. In Bamboo Fiber Composites; Jawaid, M., Mavinkere Rangappa, S., Siengchin, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 189–213.

- Xiao, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Shan, B. Design and construction of modern bamboo bridges. J. Bridge Eng. 2010, 15, 533–541.