Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Plant Sciences

|

Others

Sesquiterpene lactones (SL), characterized by their high prevalence in the Asteraceae family, are one of the major groups of secondary metabolites found in plants. Researchers from distinct research fields, including pharmacology, medicine, and agriculture, are interested in their biological potential. With new SL discovered in the last years, new biological activities have been tested, different action mechanisms (synergistic and/or antagonistic effects), as well as molecular structure–activity relationships described.

- anti-inflammatory action

- immune response

- sesquiterpene lactones

1. Introduction

Inflammation could generally be defined as a protective response by an organism triggered by pathogens or endogenous stress signals [1]. Immune cells, mostly myeloid cells, can specifically recognize pathogen-associated molecular pattern molecules (PAMPs) or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), and initiate mechanisms to eliminate the initial trigger, after which, the inflammatory process must be adequately resolved. When allowed to continue unchecked, inflammation may result in autoimmune or autoinflammatory disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, or even cancer.

The immune system is a complex network of protein and cells interactions in differentiated organs and tissues, with the goal to protect the organism from diseases and substances identified as “non-self”. This system comprises a diversity of different cell types and proteins. Each performs a specific mission, collaborating in a magnificent way to the recognition and reaction against “non-self” [2]. Despite all elements of the immune system interacting with each other, two types of immune responses can be considered: the innate immune response and the acquired immune response [3]. Innate immune responses are carried out by cells that do not need previous activation to reach their maximum response. These cells include neutrophils, monocytes/macrophages [4], eosinophils, and basophils [5][6]. Neutrophils are the main mediators of a rapid innate host defense against most bacterial and fungal pathogens, while natural killer (NK) cells are important in the early stages against intracellular pathogens, particularly killing virally infected cells [7]. These immune cells have granules and are the most abundant of all white blood cells in humans, killing microorganisms by microbicidal agents present in its granules and others produced during activation [8]. Monocytes/macrophages are white blood cells of the immune system, present in the bloodstream and tissues, respectively, which engulf and digest microbes, cellular debris, and other foreign substances that affect the health of a high number of organisms. This process, common to neutrophils, is named phagocytosis, and acts to defend the host against infection and injury [9]. Most macrophages are located at strategic points in the host organism where microbial invasion or accumulation of foreign substances are likely to occur [10]. The basophils and eosinophils correspond to a low percentage of white blood cells, having a role more specific in allergic reactions and parasitic infections [5][6]. In fact, it was suggested that eosinophils and basophils may mainly act as regulatory cells in immune responses, in the context of allergy or parasitic infections, rather than effector white blood cells, such as neutrophiles and monocytes/macrophytes [11][12].

Unlike innate immune responses, the adaptive responses are highly specific to the particular pathogens/antigens that induce them. The acquired immune system is already present at birth; immune memory formation only occurs after exposure of adaptive cells to the specific antigen. This exposure occurs throughout life, but the first three years of life is a critical period where most naive lymphocytes (B and T lymphocytes) are activated, greatly enhancing immune memory formation [13]. In autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis, due to the persistence of autoantigen, autoreactive T and B cells will be activated and maintained.

Mechanisms involving the entire inflammatory process, as well an individual’s immunomodulation response capacity, are not completely understood, but highlight extremely important cellular players, as well as multiple regulatory levels. Currently, there are a considerable number of anti-inflammatory medicines, with different therapeutic strategies that may be summarized as: (i) reducing the activity of specific cytokines or their receptors (e.g., P2 × 7 receptor inhibitors in certain viral infections [14]; cytokine suppressive anti-inflammatory drugs (CSAIDs) inhibiting NF-κB and p38 MAPK signaling to avoid pre-term birth); (ii) blocking lymphocyte trafficking into tissues (e.g., vedolizumab, an anti-α4β7 integrin, for treating Crohn’s disease [15]); (iii) prevent the binding of monocyte-lymphocyte costimulatory molecules; and (iv) deplete B lymphocytes (monoclonal antibodies against CD20, rituximab, for non-Hodgkin lymphoma [16][17]). Prolonged exposure to anti-inflammatory drugs, such as glucocorticoids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, has been described as having considerable side effects, such as susceptibility to secondary infections. The pharmaceutical companies still search for the development of more effective and less toxic anti-inflammatory agents, addressing other molecular responses, to treat either acute inflammation or chronic inflammatory diseases.

Nature is a rich source for compounds with anti-inflammatory properties. This recognition is nowadays underlined by the significant number (~25%) of FDA-approved natural anti-inflammatory drugs, which are natural product derivatives [18]. From all secondary metabolites that can be found in plants, the sesquiterpene lactones (SL) group is one of the most prevalent and biologically significant, comprising over 5000 known compounds [19]. With new SL discovered in the last years, new biological activities have been tested, as well as different mechanisms of action (synergistic and/or antagonistic) and structure–activity relationships. SL exhibited a wide range of biological activities with impacts in human health, ranging from antitumor, antimicrobial, antioxidant, hepatoprotective, among many others, reported within a large list of published manuscripts.

2. Sesquiterpene Lactones and Their Structure–Activity Relationships

Sesquiterpene lactones (SL) are a major group of secondary metabolites found in plants [19] and could generally be included in the Cactaceae, Solanaceae, Araceae, and Euphorbiaceae families, with a high prevalence in Asteraceae, where they can be found all over [19].

The medicinal properties of SL have been used since immemorial times, initially without the specific knowledge of what were SL. In folk medicine, it was usually used as part of the plants to treat numerous diseases [19]; for example, using boiled leaves of the plant Artemisia douglasiana in the treatment of gastric ulcers. These leaves present dehydroleucodine—SL with proven effects in the treatment of peptic gastric ulcers [20]. SL biological activities are associated with adjuvant treatments for a wide range of diseases, such as cancer and cardiovascular diseases, and neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s [21][22], as well as malaria, diarrheal, viral infections (influenza, herpes simplex virus, SARS-CoV-2)) [23], bacterial infections, migraines, and rheumatoid arthritis. They are even used to treat insect bites, presenting analgesic and sedative effects [24][25][26].

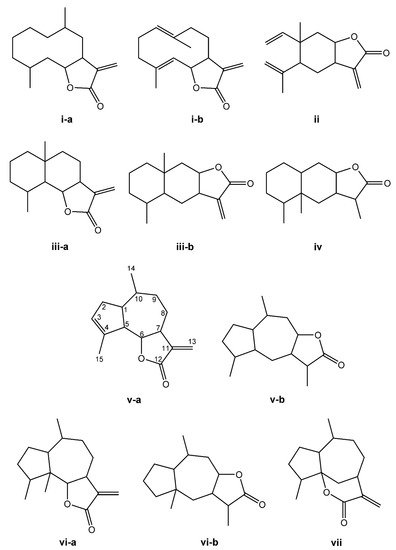

The SL are derived from two main precursors—isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) [27]. These precursors can be generated in plants via either the mevalonate pathway (MVA), which occurs within the cytosol, or the 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol (MEP) pathway, occurring in the chloroplasts [28][29]. IPP and DMAPP are converted into farnesyl diphosphate (FPP) by the enzyme farnesyl diphosphate synthase [27]. FPP is considered a common precursor for SL, but can be further converted into sterols, triterpenes, or used for prenylation of proteins. This terpene subclass can be organized based on a carbon-cyclic skeleton (Figure 1), as follows: (i) germacranolides (with a ten-membered ring); (ii) elemanolides (with a six-membered ring); (iii) eudesmanolides and (iv) eremophilanolides (both with six-membered rings); and (v) guaianolides; (vi) pseudoguaianolides; (vii) hypocretenolides (with five- and seven-membered rings, with a methyl group at the C-4 or C-5 position) [30][31].

Figure 1. Structures of the main sesquiterpene lactone-type skeletons: germacranolide isomers (i-a,i-b); elemanolide (ii); eudesmanolide isomers (iii-a,iii-b); eremophilanolide (iv); guaianolide isomers (v-a,v-b); pseudoguaianolide isomers (vi-a,vi-b); and hypocretenolide (vii).

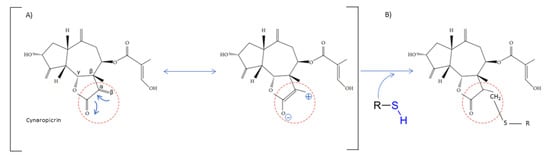

The chemical structure shares an oxygen-containing ring structure with a carbonyl function and structure–activity relationship (SAR) profile studies, attributed to the α-methylene-γ-lactone group (αM γL) and a wide range of SL biological effects, as it exerts activity by means of alkylation of thiol groups, commonly found in proteins (Figure 2) [32], demonstrated to be crucial for SL inhibitory effects upon different molecular processes. After 1991, interest in SL structure–activity relationships regained with the advent of novel methods, namely comparative molecular field analyses, quantitative fractional accessible molecular surface areas, self-organizing maps, and molecular descriptors, clearly associated to an increase in publications related to SL structure–activity relationships. According to Choodej et al., costunolide and eudesmanolide-type sesquiterpene derivatives, when synthesized with no αM γL moiety in their structures, do not show any detectable activity in terms of decreasing TNF-α, even at high concentrations (50 µmol/L) [33], in comparation to original costunolide with an IC50 value of 2.05 µmol/L [33], showing the essential role of αM γL moiety for the anti-inflammatory effect on TNF-α secretion in activated macrophages. Cynaropicrin also known to inhibit TNF-α and NO production in a dose-dependent manner [34], when treated with SH compounds (i.e., L-cysteine, dithiothreitol, and 2-mercaptoethanol) loses the inhibitory effect upon TNF-α and NO, suggesting that cynaropicrin anti-inflammatory activity is mediated by conjugation with SH-groups of target proteins [35] (Figure 2). More than 300 mM of cysteine (15-fold as a molar ratio between cynaropicrin and L-cysteine) attenuates the suppressive effect of cynaropicrin up to 90%, not only suggesting that a high molar ratio is required to completely abrogate the cynaropicrin effect, but also that the binding affinity between cynaropicrin and the target protein might be higher than that between cynaropicrin and L-cysteine [34].

Figure 2. Cynaropicrin chemical structure, with the reactive center, α-methylene-γ-lactone moiety (αM γL). The reactive centers of SL are evidentiated with red circles. (A) Michael reaction between α-methylene-γ-lactone moiety (αM γL). (B) Reaction with a sulfhydryl group.

SAR profile studies have also demonstrated that SL αM γL moiety combined with a C4-C5 epoxide ring can interact with the sulfhydryl groups through the αM γL [36], as well as with the hydroxyl and amine groups through the epoxide ring. The use of a prodrug approach, by addition of an amine group into the αM γL moiety, leads to amino-derivatives with similar biological activities, increased solubility, and improves the selectivity by reducing unspecific binding to biological thiols via the Michael-type addition to the αM γL moiety. Similar approaches were successfully applied to several SL, namely helenalin, costunolide, and parthenolide [37]. The SAR studies also demonstrated that an ester group at C-8 might be more important than the αM γL moiety for SL cytotoxicity, as it was demonstrated with 11,13-β-dihydro-lactucopicrin, lacking the αM γL moiety, but carrying an ester group at C-8, was more cytotoxic to nasopharyngeal and liver cancer cells than lactucin (the same structure but with an αM γL moiety and no ester at the C-8 position) [38].

SL carbon-cyclic skeleton molecular geometry organizations also imprint different biological activities as the structural and chemical natures also change. The germacranolides, with ten-membered rings, more easily adapt to different conformation structures and therefore turn out to be more available to interact with different biological targets, comparatively to eudesmanolides (with six-membered rings), which are more restricted in their bioactivities. The example of heliangolides, containing furane rings, have been described as more effective than guaianolides, on account to their greater conformational flexibility. Studies of structurally-related pseudoguaianolides showed that the β-OH isomer (parthenin) at C-1 is more active against ethyl phenylpropiolate-induced mouse ear edema than the α-OH equivalent (hymenin) [39].

The different studies developed over the last years using SL-derivative strategies, demonstrated the importance of different SL reactive centers, their impacts upon interaction with biological targets, as well as their capacity to potentiate their clinical relevance, namely increasing aqueous solubility, diminishing toxicity, acquiring better pharmacokinetics, among many other important features [40].

3. Sesquiterpene Lactones in Medicine: Immunoregulatory Response and Anti-Inflammatory Activities

In 2010, the SL in clinical trials were artemisinin, thapsigargin, and parthenolide [41]. Ten years later, in 2020, some SL isolated from the Asteraceae species, were already commercially available, such as artemisinin and parthenolide [41][42]. Moreover, the SL alantolactone, arglabin, costunolide, cynaropicrin, helenalin, inuviscolide, lactucin, parthenolide, thapsigargin, and tomentosin are use in in vivo studies, preclinical, and few in clinical studies. These SL show promising anti-inflammatory effects and their immunoregulatory effects deserve attention, aside from their many biological activities [43]. The cellular and molecular activities of SL will be described in detail below.

Immunomodulatory Effects of Sesquiterpene Lactones at the Cellular Level

Stimulation of immune cells lead to active inflammation through cytokine-mediated actions. Table 1 summarizes the direct activities that have been described so far, of different SL on immune cells (and key cytokines) involved in innate and acquired immune responses. Artemether, an artemisinin derivative, was found to significantly suppress the proliferation, IL-2, and interferon-γ (IFN- γ) production by T cells triggered by T cell receptor engagement [44]. Artemether significantly inhibited the T cell receptor engagement-triggered MAPK signaling pathway, including phosphorylation of ERK1/2, JNK, and p38. The authors further dissected that artemether majorly affecting the function of T cells, rather than the antigen presenting cells to exert the immunosuppressive effects [44]. Cynaropicrin presented equivalent effects upon T cell proliferation from splenocytes, as demonstrated by Cho et al. The authors studied cynaropicrin anti-mitogenic effects upon T- and B lymphocytes treated with concanavalin A, phytohemagglutinin, and lipopolysaccharide. In all cases, there was a decrease in T cell proliferation (either CD4+ or CD8+), known to play a crucial role in chronic inflammatory processes though activation of inflammatory mast cells, eosinophils, neutrophils, and macrophages, resulting in a massive production of chemical mediators and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Schepetkin et al. (2018) tested thirteen SL in regard to reduction of T cell activation [45]. The authors concluded that five SL, the arglabin, grosheimin, agracin, parthenolide, and estafiatin, could inhibit T lymphocytes receptors, therefore having immunotherapeutic properties (Table 1). Recently, the effects of 7-hydroxyfrullanoide in inhibiting CD4+ T cells and peritoneal macrophage responses were investigated. The 7-hydroxyfrullanoide reduced IL-2 and simultaneously induced Ca2+ (an intracellular chelator, which lowers lactate and rescues CD4+ T cell cycling) [46]. Moreover, intraperitoneal administration of 7-hydroxyfrullanoide lowers serum inflammatory cytokines IFN- γ, IL-6, reduces the effects of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis, and emphasizes the anti-inflammatory potential of 7-hydroxyfrullanoide in lowering immune responses [46].

Table 1. SL described as having regulatory functions upon the immune system, highlighting immunoregulatory actions within acquired and innate responses.

| Sesquiterpene Lactone | Action | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Acquired Immune Response | ||

| Reduction of T cells production | ||

| Arglabin Grosheimin Agracin Parthenolide Estafiatin |

↓ TCR | [45] |

| Artemether (an artemisinin derivative) | ↓ IL-2, interferon-γ (IFN- γ), TCR ↓ phosphorylation of ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 |

[44] |

| 7-hydroxyfrullanoide | ↓ IL-2, ↑↑ Ca2+ ⇒ ↓ CD4+ ↓ IL-6, IFN- γ |

[46] |

| Cynaropicrin | ↓ proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ T- and B- lymphocytes | [34] |

| Deoxyelephantopin Isodeoxyelephantopin |

↓ lymphocytes | [47] |

| Innate Immune Response | ||

| Macrophage Inhibition | ||

| Tagitinin C, F and A | ↑ neutrophils apoptosis, ↓ IL-6, ↓ IL-8, ↓ TNF-α | [48] |

| Neutrophils Inhibition | ||

| Diacethylpiptocarphol Hirsutinolides |

↓ neutrophil infiltration | [49] |

| Lychnopholide Eremantholide C Goyazensolide |

↓ neutrophil infiltration, ↓ TNF-α | [50] |

| Budlein A | ↓ Neutrophil recruitment, ↓ Il-1β and TNF-α mRNA | [51] |

| Alantolactone | ↓ TNF-α, ↓ IL-6 and ↓IL-17A, | [52] |

| Costunolide | ↓ Neutrophil recruitment, | [51] |

| Eosinophils Reduction | ||

| Alantolactone Costunolide Dehydrocostuslactone |

↓ Th2 cytokines (IL-4 and IL-3) | [53] |

| Damsin Neoambrosin |

Eosinophils | [54] [55] |

Abe et al. (2015) reports a role of the SL tagitinins isolated of Tithonia diversifolia in activation and survival of human neutrophils [48]. Tagitinins C, F, and A decrease IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α production by human neutrophils (Table 1), but only tagitinin F did so safely, without inducing neutrophil apoptosis. Aerial parts of Inula hupehensis Ling. have a diversity of SL (eudesmanolides, germacranolides, and xanthanolide), all with an inhibitory effect against LPS-induced nitric oxide (NO) production in macrophages [56][57] (Table 1). Moreover, Lee et al. (2018) reports in rats that the alantolactone, costunolide, and dehydrocostus lactone isolated from Saussurea costus (Falc.) Lipsch have roles in allergic asthma, by reducing the number of immune cells, particularly eosinophils, underlying SL role in allergic immunity [53] (Table 1). Moreover, in rats, the inhibitory effects of SL isolated from Eupatorium chinense L. on IgE-mediated degranulation of basophils, was reported [58]. These immune cells keep their specific secretory immune products in granules and may release them by exocytosis during an inflammatory response [59]. Therefore, the inhibition of their degranulation reduces the immune response of these cells. The effectiveness of some rich extracts of SL, e.g., Vernonia scorpioides L. ethanolic extracts, containing diacethylpiptocarphol and hirsutinolides, were tested when applied topically in acute and chronic cutaneous inflammation models in mice. The results demonstrated that topical application of ethanolic extract of Vernonia scorpioides L. reduced edema and induced myeloperoxidase activity to a comparable value to the reference drug dexamethasone, a corticosteroid [49], meaning a reduction of neutrophil infiltration. Recently, an in vivo study using lychnopholide, eremantholide C, and goyazensolide, three sesquiterpene lactones extracted from Lychnophora species, were assessed regarding their anti-inflammatory actions, using a monosodium urate (MSU) crystal-induced arthritis C57BL/6 mice animal model. The tested SL exerted anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting neutrophil migration and blocking the release of TNF-α [50]. Budlein A, a SL from Viguiera robusta, presented an in vivo response in a model of acute gout arthritis in mice. Budlein A reduced neutrophil recruitment, phagocytosis of MSU crystals by neutrophils, and Il-1β and TNF-α mRNA expression in the knee joints. In vitro, budlein A decreased TNF-α production, which might be related to the inhibition of NF-κB activation. Furthermore, budlein A reduced the IL-1β maturation, possibly by targeting inflammasome assembly in macrophages [51]. Similar results were recently obtained with alantolactone in a collagen-induced arthritis DBA/1 mouse model. Alantolactone at 50 mg/kg attenuates rheumatoid arthritis symptoms, including high arthritis scores, infiltrating inflammatory cells, synovial hyperplasia, bone erosion, and levels of the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-17A, but not IL-10 in paw tissues. The number of splenic Th17 cells and the capability of native CD4+ T cells to differentiate into the Th17 subset (one of the rheumatoid arthritis pathogenic pathways), by downregulating STAT3/RORγt signaling by as early as 24 h of treatment, was also achieved by alantolactone treatment [52]. Alantolactone therapeutic effects underlie the suppression of inflammatory cytokines and the modulation of immune response.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/molecules27031142

References

- Netea, M.G.; Balkwill, F.; Chonchol, M.; Cominelli, F.; Donath, M.Y.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Golenbock, D.; Gresnigt, M.S.; Heneka, M.T.; Hoffman, H.M.; et al. A guiding map for inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 826–831.

- Nicholson, L.B. The immune system. Essays Biochem. 2016, 60, 275–301.

- Iwasaki, A.; Medzhitov, R. Regulation of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Science 2010, 327, 291–295.

- Huber-Lang, M.; Lambris, J.D.; Ward, P.A. Innate immune responses to trauma. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 327–341.

- Kensuke Miyake, K.; Karasuyama, H. Emerging roles of basophils in allergic inflammation. Allergol. Int. 2017, 66, 382–391.

- Nagata, M.; Nakagome, K.; Soma, T. Mechanisms of eosinophilic inflammation. Asia Pac. Allergy 2020, 10, e14.

- Malech, H.L.; DeLeo, F.R.; Quinn, M.T. The Role of Neutrophils in the Immune System: An Overview. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1124, 3–10.

- Borregaard, N. Neutrophils, from Marrow to Microbes. Immunity 2010, 24, 657–670.

- Mosser, D.M.; Edwards, J.P. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 958–969.

- Hulsmans, M.; Clauss, S.; Xiao, L.; Aguirre, A.D.; King, K.R.; Hanley, A.; Hucker, W.J.; Wülfers, E.M.; Seemann, G.; Courties, G.; et al. Macrophages Facilitate Electrical Conduction in the Heart. Cell 2017, 169, 510–522.

- Nourshargh, S.; Alon, R. Leukocyte Migration into Inflamed Tissues. Immunity 2014, 41, 694–707.

- Chirumbolo, S.; Bjørklund, G.; Sboarina, A.; Vella, A. The role of basophils as innate immune regulatory cells in allergy and immunotherapy. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2018, 14, 815–831.

- Holgate, S.T. Innate and adaptive immune responses in asthma. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 673–683.

- Savio, L.E.B.; de Andrade Mello, P.; da Silva, C.G.; Coutinho-Silva, R. The P2X7 Receptor in Inflammatory Diseases: Angel or Demon? Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 52.

- Veny, M.; Fernández-Clotet, A.; Panés, J. Controlling leukocyte trafficking in IBD. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 159, 105050.

- Plosker, G.L.; Figgitt, D.P. Rituximab. Drugs 2003, 63, 803–843.

- Dinarello, C.A. Anti-inflammatory Agents: Present and Future. Cell 2010, 140, 935–950.

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Nearly Four Decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 770–803.

- Chadwick, M.; Trewin, H.; Gawthrop, F.; Wagstaff, C. Sesquiterpenoids lactones: Benefits to plants and people. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 12780–12805.

- Repetto, M.; María, A.; Guzmán, J.; Giordano, O.; Llesuy, S. Protective effect of Artemisia douglasiana Besser extracts in gastric mucosal injury. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2003, 55, 551–557.

- Robles, M.; Wang, N.; Kim, R.; Choi, B.H. Cytotoxic effects of repin, a principal sesquiterpene lactone of Russian knapweed. J. Neurosci. Res. 1997, 47, 90–97.

- Ma, C.; Meng, C.-W.; Zhou, Q.-M.; Peng, C.; Liu, F.; Zhang, J.-W.; Zhou, F.; Xiong, L. New sesquiterpenoids from the stems of Dendrobium nobile and their neuroprotective activities. Fitoterapia 2019, 138, 104351.

- Manayi, A.; Nabavi, S.M.; Khayatkashani, M.; Habtemariam, S.; Khayat Kashani, H.R. Arglabin could target inflammasome-induced ARDS and cytokine storm associated with COVID-19. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 8221–8225.

- Abood, S.; Eichelbaum, S.; Mustafi, S.; Veisaga, M.-L.; López, L.A.; Barbieri, M. Biomedical Properties and Origins of Sesquiterpene Lactones, with a Focus on Dehydroleucodine. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017, 12, 1934578X1701200638.

- Fuzimoto, A.D. An overview of the anti-SARS-CoV-2 properties of Artemisia annua, its antiviral action, protein-associated mechanisms, and repurposing for COVID-19 treatment. J. Integr. Med. 2021, 19, 375–388.

- Treml, J.; Gazdová, M.; Šmejkal, K.; Šudomová, M.; Kubatka, P.; Hassan, S.T.S. Natural Products-Derived Chemicals: Breaking Barriers to Novel Anti-HSV Drug Development. Viruses 2020, 12, 154.

- Chang, W.-C.; Song, H.; Liu, H.w.; Liu, P. Current development in isoprenoid precursor biosynthesis and regulation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2013, 17, 571–579.

- Nagegowda, D.A. Plant volatile terpenoid metabolism: Biosynthetic genes, transcriptional regulation and subcellular compartmentation. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 2965–2973.

- Bach, T.J.; Rohmer, M. Isoprenoid Synthesis in Plants and Microorganisms: New Concepts and Experimental Approaches; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012.

- Fernandes, M.B.; Scotti, M.T.; Ferreira, M.J.P.; Emerenciano, V.P. Use of self-organizing maps and molecular descriptors to predict the cytotoxic activity of sesquiterpene lactones. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 43, 2197–2205.

- Ghantous, A.; Gali-Muhtasib, H.; Vuorela, H.; Saliba, N.A.; Darwiche, N. What made sesquiterpene lactones reach cancer clinical trials? Drug Discov. Today 2010, 15, 668–678.

- Kupchan, S.M.; Eakin, M.A.; Thomas, A.M. Tumor inhibitors. 69. Structure-cytotoxicity relationships among the sesquiterpene lactones. J. Med. Chem. 1971, 14, 1147–1152.

- Choodej, S.; Pudhom, K.; Mitsunaga, T. Inhibition of TNF-α-Induced Inflammation by Sesquiterpene Lactones from Saussurea lappa and Semi-Synthetic Analogues. Planta Med. 2018, 84, 329–335.

- Cho, J.Y.; Baik, K.U.; Jung, J.H.; Park, M.H. In vitro anti-inflammatory effects of cynaropicrin, a sesquiterpene lactone, from Saussurea lappa. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000, 398, 399–407.

- Yang, Y.I.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, K.T.; Choi, J.H. Costunolide induces apoptosis in platinum-resistant human ovarian cancer cells by generating reactive oxygen species. Gynecol. Oncol. 2011, 123, 588–596.

- Schmidt, T.J. Structure-Activity Relationships of Sesquiterpene Lactones. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Attaur, R., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 33, pp. 309–392.

- Woods, J.R.; Mo, H.; Bieberich, A.A.; Alavanja, T.; Colby, D.A. Amino -derivatives of the sesquiterpene lactone class of natural products as prodrugs. MedChemComm 2013, 4, 27–33.

- Ren, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, X.; Ye, Y. Discovery, Structural Determination and Anticancer Activities of Lactucinlike Guaianolides. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2005, 2, 444–450.

- Recio, M.C.; Giner, R.M.; Uriburu, L.; Máñez, S.; Cerdá, M.; De La Fuente, J.R.; Ríos, J.L. In vivo activity of pseudoguaianolide sesquiterpene lactones in acute and chronic inflammation. Life Sci. 2000, 66, 2509–2518.

- Wang, J.; Su, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhai, S.; Sheng, R.; Wu, W.; Guo, R. Structure-activity relationship and synthetic methodologies of α-santonin derivatives with diverse bioactivities: A mini-review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 175, 215–233.

- Ghantous, A.; Sinjab, A.; Herceg, Z.; Darwiche, N. Parthenolide: From plant shoots to cancer roots. Drug Discov. Today 2013, 18, 894–905.

- Aguiar, A.C.C.; RochaI, E.M.M.; SouzaI, N.B.; FrançaI, T.C.C.; Krettli, A.U. New approaches in antimalarial drug discovery and development—A Review. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2012, 107, 831–845.

- Moujir, L.; Callies, O.; Sousa, P.; Sharopov, F.; Seca, A.M. Applications of Sesquiterpene Lactones: A Review of Some Potential Success Cases. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3001.

- Wang, J.X.; Tang, W.; Shi, L.P.; Wan, J.; Zhou, R.; Ni, J.; Fu, Y.F.; Yang, Y.F.; Li, Y.; Zuo, J.P. Investigation of the immunosuppressive activity of artemether on T-cell activation and proliferation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 150, 652–661.

- Schepetkin, I.A.; Kirpotina, L.N.; Mitchell, P.T.; Kishkentaeva, A.S.; Shaimerdenova, Z.R.; Atazhanova, G.A.; Adekenov, S.M.; Quinn, M.T. The natural sesquiterpene lactones arglabin, grosheimin, agracin, parthenolide, and estafiatin inhibit T cell receptor (TCR) activation. Phytochemistry 2018, 146, 36–46.

- Pathak, S.; Gokhroo, A.; Kumar Dubey, A.; Majumdar, S.; Gupta, S.; Almeida, A.; Mahajan, G.B.; Kate, A.; Mishra, P.; Sharma, R.; et al. 7-Hydroxy Frullanolide, a sesquiterpene lactone, increases intracellular calcium amounts, lowers CD4+ T cell and macrophage responses, and ameliorates DSS-induced colitis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 97, 107655.

- Geetha, B.S.; Nair, M.S.; Latha, P.G.; Remani, P. Sesquiterpene lactones isolated from Elephantopus scaber L. inhibits human lymphocyte proliferation and the growth of tumour cell lines and induces apoptosis in vitro. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 721285.

- Abe, A.; Oliveira, C.E.; Dalboni, T.M.; Chagas-Paula, D.A.; Rocha, B.A.; Oliveira, R.B.; Gasparoto, T.H.; Costa, F.B.; Campanellia, A.P. Anti-inflammatory sesquiterpene lactones from Tithonia diversifolia trigger different effects on human neutrophils. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2015, 25, 111–116.

- Rauh, L.K.; Horinouchi, C.D.; Loddi, A.M.; Pietrovski, E.F.; Neris, R.; Souza-Fonseca-Guimarães, F.; Buchi, D.F.; Biavatti, M.W.; Otuki, M.F.; Cabrini, D.A. Effectiveness of Vernonia scorpioides ethanolic extract against skin inflammatory processes. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 138, 390–397.

- Bernardes, A.C.F.P.F.; Matosinhos, R.C.; de Paula Michel Araújo, M.C.; Barros, C.H.; de Oliveira Aguiar Soares, R.D.; Costa, D.C.; Sachs, D.; Saúde-Guimarães, D.A. Sesquiterpene lactones from Lychnophora species: Antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant pathways to treat acute gout. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 269, 113738.

- Fattori, V.; Zarpelon, A.C.; Staurengo-Ferrari, L.; Borghi, S.M.; Zaninelli, T.H.; Da Costa, F.B.; Alves-Filho, J.C.; Cunha, T.M.; Cunha, F.Q.; Casagrande, R.; et al. Budlein A, a Sesquiterpene Lactone from Viguiera robusta, Alleviates Pain and Inflammation in a Model of Acute Gout Arthritis in Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1076.

- Chen, H.-L.; Lin, S.C.; Li, S.; Tang, K.-T.; Lin, C.-C. Alantolactone alleviates collagen-induced arthritis and inhibits Th17 cell differentiation through modulation of STAT3 signalling. Pharm. Biol. 2021, 59, 134–145.

- Lee, B.K.; Park, S.J.; Nam, S.Y.; Kang, S.; Hwang, J.; Lee, S.J.; Im, D.S. Anti-allergic effects of sesquiterpene lactones from Saussurea costus (Falc.) Lipsch. determined using in vivo and in vitro experiments. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 213, 256–261.

- Butturini, E.; Prati, A.C.; Boriero, D.; Mariotto, S. Natural Sesquiterpene Lactones Enhance Chemosensitivity of Tumor Cells through Redox Regulation of STAT3 Signaling. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 4568964.

- Jeon, W.J.; Kim, K.M.; Kim, E.J.; Jang, W.G. Costunolide increases osteoblast differentiation via ATF4-dependent HO-1 expression in C3H10T1/2 cells. Life Sci. 2017, 178, 94–99.

- Qin, J.J.; Zhu, J.X.; Zeng, Q.; Cheng, X.R.; Zhang, S.D.; Jin, H.Z.; Zhang, W.D. Sesquiterpene lactones from Inula hupehensis inhibit nitric oxide production in RAW264.7 macrophages. Planta Med. 2012, 78, 1002–1009.

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, T.; Ke, C.Q.; Tang, C.; Yao, S.; Lin, L.; Ye, Y. Sesquiterpene lactone dimers from Artemisia lavandulifolia inhibit interleukin-1β production in macrophages through activating autophagy. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 105, 104451.

- Itoh, T.; Oyama, M.; Takimoto, N.; Kato, C.; Nozawa, Y.; Akao, Y.; Linuma, M. Inhibitory effects of sesquiterpene lactones isolated from Eupatorium chinense L. on IgE-mediated degranulation in rat basophilic leukemia RBL-2H3 cells and passive cutaneous anaphylaxis reaction in mice. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 3189–3197.

- Dvorak, A.M. Degranulation of Basophils and Mast Cells. In Basophil and Mast Cell Degranulation and Recovery; Dvorak, A.M., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1991; Volume 4, pp. 105–275.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!