3. Estrogenic Effects of Parabens

Despite the limited epidemiological evidence linking paraben exposure with breast cancer, recent in vitro and animal studies have shed light on the endocrine-modulating effects of parabens, suggesting that parabens may be implicated in breast carcinogenesis.

Estrogen is the primary sex hormone responsible for mammary gland development during critical life stages [

38,

39]. The pubertal surge of secretion of estrogen and progesterone from the ovaries stimulates proliferation of the myoepithelial cells within ducts [

40,

41]. In addition, estrogen induces growth and branching of mammary ducts in cooperation with other growth factors by activating the estrogen receptors (ER) located in the epithelium and stromal cells [

42,

43,

44].

The estrogenic activity of parabens has been well documented and characterized [

2,

10,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50]. Parabens have been shown to regulate ER-mediated gene expression in vitro [

2,

45,

46,

47,

48]. MP, EP, PP, BP, and BzP have an estradiol equivalence factor (EEF) of 1.25 × 10

−7, 6.48 × 10

−7, 2.39 × 10

−6, 8.09 × 10

−6, and 1.35 × 10

−5 respectively [

13]. In silico simulation has shown that MP and EP interact with the agonist-binding pocket of human ERα. MP and EP bound to Glu353 and Arg394 of human ER with binding energies of −49.35 and −53.38 kcal/mol, respectively. Both Glu353 and Arg394 are located at the ligand-binding pocket of the ER known to play a critical role in human ERα–17β-estradiol (E2) interaction [

49]. The values of the negative binding energy indicate that the binding of parabens to ERα is likely to be a spontaneous process. The stimulatory effects on the proliferation of breast cancerous MCF-7 and noncancerous MCF-10A cells in response to either a single or repetitive exposure to MP, PP, or BP were studied [

51]. While all tested parabens increased cell proliferation of MCF-7 cells, only MP and BP at low doses increased MCF-10A cells proliferation after a single exposure, but not repeated exposure. Moreover, MP, PP, and BP exposure at low doses significantly increased E2 secretion in MCF-7 cells, but they all had the opposite effect on MCF-10A cells [

51].

Table 2 summarizes the differential effects of parabens on the gene expression of ER and progesterone receptor (PR) in MCF 7 vs. MCF-10 A cells [

52]. Interesting, the effect of parabens on ERα and ERβ can be effectively blocked by ICI 182,780, the ER antagonist, in the MCF-7 cells [

52]. In contrast, co-treatment with ICI 182,780 did not attenuate the stimulatory effect of parabens on either ERα or ERβ in the MCF-10A cells [

52]. ERα and ERβ seem to play opposing roles in regulating growth and differentiation in response to estrogens in the breasts [

53,

54]. PR, an estrogen-regulated protein, is among the most important prognostic and predictive markers of response to endocrine therapies in breast cancer patients [

55]. PR acts as a critical factor in the induction, progression, and maintenance of the neoplastic phenotype of ER-positive breast cancer [

56]. Future studies are warranted to understand the biological implications of differential actions of parabens on ERs and PR in cancerous vs. noncancerous breast epithelial cells.

Table 2. Effect of 17β-estradiol (E2) and Parabens on Estrogen and Progesterone Receptors Gene and Protein Expression [

52].

The differential effect of parabens on the expression of genes related to cell cycle control and apoptosis has been investigated in MCF-7 and MCF-10A cells [

57]. As shown in

Table 3, these results further demonstrated variabilities in gene expression between cancerous and noncancerous breast epithelial cell lines in response to parabens. The discrepancy in cellular behavior between cancerous and noncancerous breast epithelia in response to parabens may suggest that parabens’ effects could be cell type-specific.

Table 3. Effect of 17-β Estradiol (E2) and Parabens on the Expression of Selected Genes in MCF-7 and MCF-10A [

57].

Global changes in gene expression profiles in response to parabens or E2 treatment have been studied in MCF-7 cells [

58]. MCF-7 cells treated for 3 days with EP, PP, and BP, but not MP, showed gene expression profiles that correlated well with those genes in response to E2 treatment and the length of the alkyl chain of parabens was crucial for the estrogen-like profiles [

58]. MCF-7 cells were also treated with 5 × 10

−4 M MP, 10

−5 M BP, or 10

−8 M E2 for 7 days and the global gene expression profiles in response to the treatments were compared [

59]. Of the 19,881 human genes investigated, 1972 genes were altered by ≥2-fold by MP, 1,292 genes were altered by ≥2-fold by BP, and 857 genes were altered ≥2-fold by E2. Only 61 genes were upregulated ≥2-fold by MP, BP and E2, while 198 genes were downregulated by ≥2-fold by all three test compounds [

59]. Therefore, the majority of genes did not follow the same pattern of regulation by all three treatments in MCF-7 cells [

59]. These results demonstrated that although parabens are estrogenic, their mimicry of E2 in global gene expression patterns is not perfect. Differences in gene expression profiles in cells in response to parabens could lead to different biological and developmental trajectories compared to the cells exposed to E2 [

59].

In vivo studies of the effects of parabens on dynamic histological changes in mammary gland development have been studied in Sprague-Dawley rats [

60]. Compared to the rats treated with the vehicle control, MP at doses that mimic human exposure levels during perinatal, prepuberty, and puberty significantly decreased amount of adipose tissue while increased expansion of the ductal tree and/or elevated amount of glandular tissue with a higher degree of branching. The authors identified puberty as the window of heightened sensitivity to MP, with increased glandular tissue and differential expression of 295 genes with significant enrichment of genes involved in DNA replication and cell cycle regulation [

60]. It is worth noting that the genes modified by MP are also well represented in the gene signature profiles of human breast cancer, suggesting a possible link between MP exposure during the critical window of breast development and a higher risk of breast cancer [

60].

In vivo studies of the effects of parabens on breast cancer initiation and progression are still scarce. In one study, MP at the levels that are commonly used in personal care products promoted the development of larger tumors than the placebo treatment in the nude mice xenografted with ER+ MCF-7 cells. Similarly, MP treatment significantly increased the volume of human patient-derived xenograft breast tumors compared to the placebo [

61]. Additional in vivo studies using different breast cancer animal models are necessary to understand the full extent of the effects of parabens on breast cancer development.

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

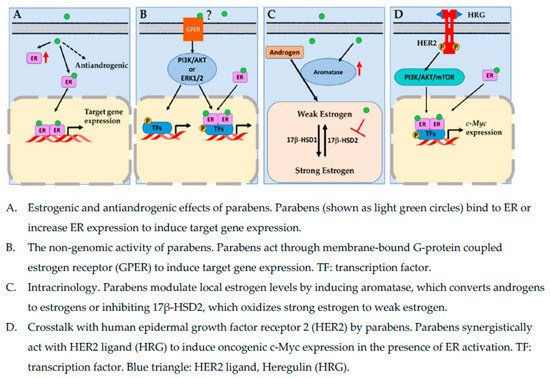

Parabens are a group of EDCs commonly found in personal care products, foods, and pharmaceuticals. Systemic exposure to parabens has been confirmed by the ubiquitous detection of parabens in human blood and urine samples. The main concerns regarding parabens use in consumer products are their potential mimicry of endogenous hormones, possible cross-talks with other signal transduction pathways, such as HER2 signaling pathway, that are pivotal in the development of breast cancer, and modulation of key enzymes involved in local estrogen metabolism. Estrogen receptor is a key transcriptional factor that drives the oncogenesis and growth of hormonally sensitive breast cells. However, the recurrence and resistance to endocrine therapy of certain types of breast cancer, indicate that underlying mechanisms of breast cancer development are likely complex, involving multiple signaling pathways. Figure 1 highlights some possible mechanisms by which parabens affect breast cancer development.

Figure 1. Molecular mechanisms by which parabens act in breast cancer cells.

Although some research findings have suggested that parabens may negatively interfere with some endocrine targets relevant to breast carcinogenesis, evidence from in vivo and epidemiological studies linking paraben exposure to breast cancer is limited. So far, most studies have focused on one single paraben and/or the direct modulating effects of parabens on sex hormone receptors. Parabens are known to have significantly lower binding affinities to estrogen receptors than their endogenous counterparts. Therefore, the direct link of the estrogenic effect of parabens to breast carcinogenesis is debatable.

Future studies investigating paraben mixtures and their cross-talks with other EDCs or signaling pathways both in vivo and in vitro are warranted. For now, cautions should be taken when individuals, including breast cancer patients or individuals with high risk of breast cancer, make the decisions on personal care products containing parabens.