Mitochondrial proteins are encoded by both nuclear and mitochondrial DNA. While some of the essential subunits of the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complexes responsible for cellular ATP production are synthesized directly in the mitochondria, most mitochondrial proteins are first translated in the cytosol and then imported into the organelle using a sophisticated transport system. These proteins are directed mainly by targeting presequences at their N-termini. These presequences need to be cleaved to allow the proper folding and assembly of the pre-proteins into functional protein complexes. In the mitochondria, the presequences are removed by several processing peptidases, including the mitochondrial processing peptidase (MPP), the inner membrane processing peptidase (IMP), the inter-membrane processing peptidase (MIP), and the mitochondrial rhomboid protease (Pcp1/PARL). Their proper functioning is essential for mitochondrial homeostasis as the disruption of any of them is lethal in yeast and severely impacts the lifespan and survival in humans.

- mitochondrial processing peptidases

- MPP

- MIP

- IMP

- mitochondrial rhomboid protease

- mitochondrial disease

1. Introduction

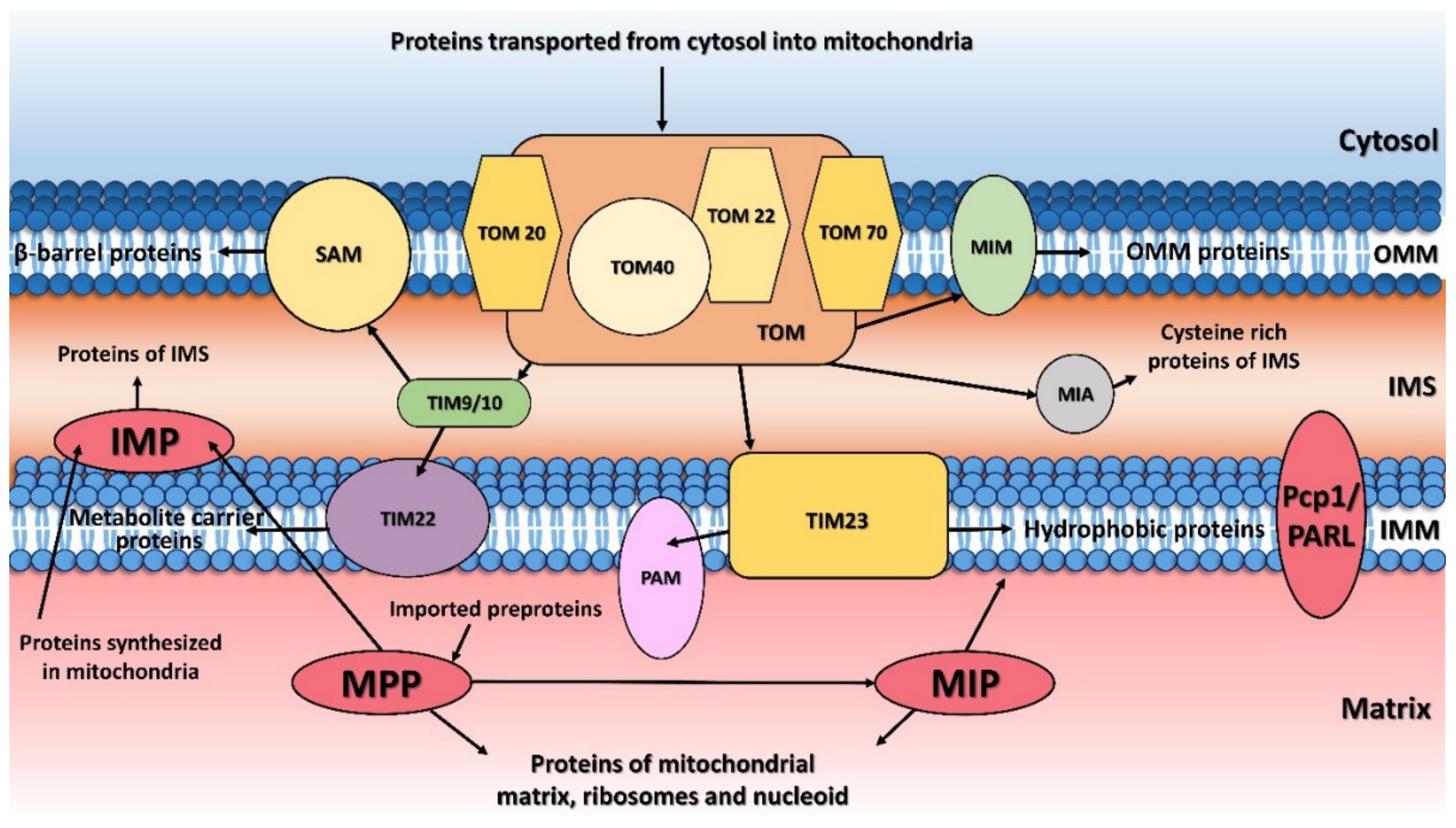

Figure 1. Protein transport and processing from cytosol to mitochondria. MTS (mitochondrial targeting sequence)-carrying pre-proteins are imported through the TOM and TIM23 complexes. Proteins containing hydrophobic sorting signal are embedded into the inner membrane (IMM), while hydrophilic proteins are sent into the mitochondrial matrix through the PAM (protein import motor) complex. Cysteine-rich proteins are imported by the TOM and MIA protein translocation systems. The precursors of β-barrel proteins are translocated through the TOM and TIM9/10 complexes and sorted and assembled by the SAM complex. Metabolite carrier precursors are imported via TOM, TIM9/10 and TIM22, and several α-helical outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) proteins are imported by the MIM complex. Pre-proteins imported into the mitochondria are processed by the mitochondrial processing peptidase (MPP) and later by the mitochondrial intermembrane peptidase (IMP) or mitochondrial intermediate peptidase (MIP). Proteins synthesized inside the mitochondria themselves are processed by IMP. Some inner membrane proteins are processed by rhomboid protease Pcp1/PARL. OMM, mitochondrial outer membrane; IMM, mitochondrial inner membrane; IMS, intermembrane space.

Figure 1. Protein transport and processing from cytosol to mitochondria. MTS (mitochondrial targeting sequence)-carrying pre-proteins are imported through the TOM and TIM23 complexes. Proteins containing hydrophobic sorting signal are embedded into the inner membrane (IMM), while hydrophilic proteins are sent into the mitochondrial matrix through the PAM (protein import motor) complex. Cysteine-rich proteins are imported by the TOM and MIA protein translocation systems. The precursors of β-barrel proteins are translocated through the TOM and TIM9/10 complexes and sorted and assembled by the SAM complex. Metabolite carrier precursors are imported via TOM, TIM9/10 and TIM22, and several α-helical outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) proteins are imported by the MIM complex. Pre-proteins imported into the mitochondria are processed by the mitochondrial processing peptidase (MPP) and later by the mitochondrial intermembrane peptidase (IMP) or mitochondrial intermediate peptidase (MIP). Proteins synthesized inside the mitochondria themselves are processed by IMP. Some inner membrane proteins are processed by rhomboid protease Pcp1/PARL. OMM, mitochondrial outer membrane; IMM, mitochondrial inner membrane; IMS, intermembrane space.2. Mitochondrial Processing Peptidase

The principal responsibility of the mitochondrial processing peptidase is to remove the N-terminal targeting presequences of proteins imported into the mitochondria (Figure 1). Although the presequences can vary in length and amino-acid composition, they have several common properties. They are all predicted to form an amphiphilic α-helix [20][21], have an overall positive charge, and have an arginine residue at position -2 or -3 from the cleavage site [22].

MPP is a hetero-dimeric protein consisting of two subunits, α and β, which are referred to as PMPCA and PMPCB in humans [11][12]. These subunits together create a large substrate-binding cavity with a Zn2+-binding site on the MPPβ subunit. The site itself is created by a conserved HxxEHx76E motif in the MPPβ subunit; the mutation of any of these residues eliminates Zn2+ binding and blocks the peptidase activity. Although the β subunit contains the entirety of the catalytic site, the cooperation of action of both MPP subunits is required for proper processing of pre-proteins. The most conserved part of all known MPPα subunits is a glycine-rich loop (GRL; residues G284GGGSFSAGGPGKGMYS300 in yeast MPPα), which is essential for substrate binding [23][24] and which moves the precursor protein towards the active site through a multistep process [25]. An electrostatic analysis of MPP complexed to a peptide substrate showed that the binding cavity was strongly negatively-charged while the substrate peptide is positively charged.

Deletion of both MPP encoding genes (MPPA and MPPB) is incompatible with the viability of S. cerevisiae under any and all growth conditions, including even anaerobic growth [26][27]. In humans, mutations in either PMPCA or PMPCB cause mitochondrial diseases that are characterized by neurological disorder with an early childhood onset and a severe neurodegenerative course [28][29][30] (Table 1).

| Processing Peptidase | Protein Variant | Disease, Symptoms | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| PMPCA | Homozygous mutation: c.1129G>A (p.Ala377Thr) Heterozygous mutations: c.287C>T (p.Ser96Leu) with c.1543G>A (p.Gly515Arg) |

SCAR2 with non- or slowly progressive cerebellar ataxia and developmental delay | [31] |

| Homozygous mutation: c.766G>A (p.Val256Met) | slowly progressive SCAR2 without intellectual disability | [32] | |

| Heterozygous mutation: c.677C>T (p.Arg223Cys) with c.853del (p.Asp285Ilefs*16) | SCAR2 with progressive cerebellar ataxia and onset in infancy | [18] | |

| Heterozygous mutations: c.1066G>A (p.Gly356Ser) with c.1129G>A (p.Ala377Thr) | SCAR2 with progressive, extensive brain atrophy, muscle weakness, visual impairment, respiratory defects | [33] | |

| Homozygous mutation: c.553C>T (p.Arg185Thr) | SCAR2 with psychomotor delay | [34] | |

| PMPCB | Heterozygous mutations: c.523C>T (p.Arg175Cys) with c.601G>C (p.Ala201Pro); c.524G>A (p.Arg175His) with c.530T>G (p.Val177Gly) Homozygous mutation: c.1265T>C (p.Ile422Thr) |

Prominent cerebellar atrophy in early childhood | [35] |

| IMMP2L | Duplication: 46,XY,dup(7)(q22.1-q31.1) | GTS/TS | [15] |

| Deletions ranged from ~49 kb to ~337 kb | Neurological disorders (ADHD, GTS/TS, OCD, ASD, Asperger′s syndrome, schizophrenia and developmental delay) | [36][37][38][39] | |

| Base pair change | Autism | [40] | |

| Copy number variation | Alzheimer′s disease | [41] | |

| Downregulation | Prostate cancer | [42] | |

| MIP | Homozygous SNV: p.K343E Heterozygous SNVs: p.L582R with p.L71Q; p.E602* with p.L306 and p.H512D with 1.4-Mb deletion of 13q12.12 |

LVNC and developmental delay, seizures, hypotonia | [43] |

| Heterozygous mutation: c.916C > T (p.Leu306Phe) with c.1970 + 2 T>A (p.Ala658Lysfs*38) | Developmental delay, hypotonia and intellectual disability | [44] | |

| Hypomethylation | Metabolic syndrome | [45] | |

| Downregulation | Prostate cancer | [42] | |

| PARL | Reduced levels | Type 2 diabetes | [19] |

| Leu262Val polymorphism | Increased plasma insulin concentration | [46] | |

| Mutation: c.230G>A (p.Ser77Asn) | Parkinson′s disease | [47] |

3. Mitochondrial Inner Membrane Peptidase

The mitochondrial inner membrane peptidase is responsible for the maturation of proteins transported into the mitochondrial inter-membrane space (Figure 1) [48][49][50][51]. These include mature proteins synthesized both within the mitochondria (e.g., yeast mitochondrially encoded subunit 2 of cytochrome c oxidase, Cox2), or nuclear-encoded proteins synthesized in the cytosol and then transported into the mitochondria (e.g., yeast cytochrome b2, Cyb2, cytochrome c1, Cyt1, and NADH cytochrome b5 reductase, Mcr1).

Structurally, IMP consists of two subunits; in humans, these are IMMP1L (inner membrane mitochondrial peptidase 1-like) and IMMP2L (inner membrane mitochondrial peptidase 2-like) [49], and in S. cerevisiae there are three subunits, Imp1, Imp2, and Som1 [50]. Although the sequence identities between the individual yeast and human IMP homologues are relatively low (between 25-37%), their tertiary structures share a number of common features. All four IMP homologues are predicted to have a membrane-anchored α-helical N-terminal domain and a catalytic C-terminal domain. The yeast Imp1 and Imp2 subunits share 31% amino-acid sequence identity and both possess catalytic activity and are bound to the inner mitochondrial membrane [52][53][54]. The catalytic domain possesses a catalytic Ser/Lys dyad, which is present in all four proteins and is structurally located in the C-terminal region [51][55]. The third yeast subunit, Som1, most likely serves to recognize substrates and was shown to physically interact with Imp1 [51][56]. Surprisingly, Som1 seems to be important for the Imp1-mediated proteolytic processing of Cox2 and Mcr1, but not for the maturation of the Cyb2 and Cyt1 cytochromes processed by the Imp2 subunit [51][56].

The currently known natural Imp1 substrates all possess a characteristic [I/V][H/D/F/M][N](↓)[D/E] amino-acid motif surrounding the cleavage site (indicated by ↓) [67]. Although the substrate specificities for Imp1 and Imp2 do not overlap, there are recognizable similarities between the protein precursors that they cleave. These include a hydrophobic residue at position -3 from the cleavage site and, for the nucleus-encoded substrates, the distances between the transmembrane segment and the cleavage site are also preserved. The accessibility of the cleavage site to the peptidase is also a prerequisite for cleavage by IMP [50].

In humans, the IMP homolog, IMMP2L has a 41% similarity to the yeast Imp2 subunit and a 90% similarity to the mouse IMMP2L [49]. It is composed of 175 amino acids with a gene of 860 kb located on chromosome 7q (AUTS1 locus), whose integrity has been shown to be critical for the development of autism spectrum disorders (ASDs). IMMP2L is expressed at a basal level in all human tissues except for the lungs and liver of adults [15][36]. Mutations associated with the gene encoding IMMP2L have been observed in several neurodegenerative diseases, including Gills de la Tourette syndrome or Tourette′s syndrome (GTS/TS), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), ASD, and schizophrenia [36][37][39][57][58] (see Table 1 above).

4. Mitochondrial Intermediate Peptidase

The mitochondrial intermediate peptidase is important for the maturation of a subgroup of precursor proteins imported into the mitochondrial matrix or embedded into the mitochondrial inner membrane [59]. These pre-proteins are first processed by MPP and only afterwards by MIP, which cleaves an additional octapeptide following MPP cleavage. The cleavage site targeted by MIP is characterized by an RX(↓)(F/L/I)XX(T/S/G)XXXX(↓) motif [48] and is located at the C-terminus of a leader peptide (↓). Active MIP is a soluble monomer of 75 kDa in yeast and 81 kDa in humans. Its proteolytic activity is stimulated by manganese, magnesium and calcium ions while 1 mM Co2+, Fe2+ or Zn2+ completely inhibits it. Unlike MPP, MIP is also sensitive to N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) and other sulfhydryl reagents [60].

Positioning at the substrate N-terminus and a large hydrophobic residue (phenylalanine, leucine and isoleucine) at position -8 from the cleavage site are both essential features for cleavage by MIP; this type of substrate specificity is not shared by any other known peptidase [48].

In S. cerevisiae, mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is severely affected when mip1 is missing. Branda et al. [48] showed that at least three vital components of the yeast mitochondrial gene expression machinery—mitochondrial small ribosomal subunit protein MrpS28, single-stranded DNA-binding protein Rim1, and elongation factor Tuf1—are processed by MIP. These proteins are essential for maintaining mitochondrial protein synthesis and mitochondrial DNA replication, which explains why the loss of mip1 impairs the mitochondrially encoded OXPHOS subunits. MIP1 disruption also results in the failure of at least two yeast nuclear-encoded respiratory chain components, the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 4 (Cox4) and the Rieske iron-sulfur protein of cytochrome bc1 catalytic subunit, to be cleaved [59].

In humans, MIP is encoded by the MIPEP gene, which contains 19 exons and is located on chromosome 13q12.12 [61]. MIPEP is expressed at high levels in energy-dependent tissues, such as the heart, brain, skeletal muscles, and pancreas [61][62][63]. Previously, some patients were reported with mutations in MIPEP which may have been linked to their diagnoses, but the first study showing that MIPEP is truly involved in a human disease was published in 2016 by Eldomery et al. [43] (see Table 1 above). They identified several single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in the MIPEP gene that caused a loss of MIP function in four unrelated patients suffering from an oxidative phosphorylation deficiency. Further studies in human fibroblasts showed that MIP has an important role in OXPHOS function since its loss impaired the processing of several OXPHOS subunits, including the OXPHOS complexes I, IV and V [44].

5. Mitochondrial Rhomboid Protease

6. Conclusions

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms23031297

References

- Chacinska, A.; Koehler, C.M.; Milenkovic, D.; Lithgow, T.; Pfanner, N. Importing Mitochondrial Proteins: Machineries and Mechanisms. Cell 2009, 138, 628–644.

- Wiedemann, N.; Pfanner, N. Mitochondrial Machineries for Protein Import and Assembly. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 685–714.

- Kulawiak, B.; Höpker, J.; Gebert, M.; Guiard, B.; Wiedemann, N.; Gebert, N. The mitochondrial protein import machinery has multiple connections to the respiratory chain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Bioenerg. 2013, 1827, 612–626.

- Shiota, T.; Imai, K.; Qiu, J.; Hewitt, V.L.; Tan, K.; Shen, H.-H.; Sakiyama, N.; Fukasawa, Y.; Hayat, S.; Kamiya, M.; et al. Molecular architecture of the active mitochondrial protein gate. Science 2015, 349, 1544–1548.

- Straub, S.P.; Stiller, S.B.; Wiedemann, N.; Pfanner, N. Dynamic organization of the mitochondrial protein import machinery. Biol. Chem. 2016, 397, 1097–1114.

- Moulin, C.; Caumont-Sarcos, A.; Ieva, R. Mitochondrial presequence import: Multiple regulatory knobs fine-tune mitochondrial biogenesis and homeostasis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Bioenerg. 2019, 1866, 930–944.

- Nicolas, E.; Tricarico, R.; Savage, M.; Golemis, E.A.; Hall, M.J. Disease-Associated Genetic Variation in Human Mitochondrial Protein Import. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 104, 784–801.

- Priesnitz, C.; Becker, T. Pathways to balance mitochondrial translation and protein import. Genes Dev. 2018, 32, 1285–1296.

- Poveda-Huertes, D.; Mulica, P.; Vögtle, F.N. The versatility of the mitochondrial presequence processing machinery: Cleavage, quality control and turnover. Cell Tissue Res. 2017, 367, 73–81.

- Becker, T.; Vögtle, F.-N.; Stojanovski, D.; Meisinger, C. Sorting and assembly of mitochondrial outer membrane proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Bioenerg. 2008, 1777, 557–563.

- Gakh, O.; Cavadini, P.; Isaya, G. Mitochondrial processing peptidases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Bioenerg. 2002, 1592, 63–77.

- Kutejová, E.; Kučera, T.; Matušková, A.; Janata, J. Mitochondrial Processing Peptidase. In Handbook of Proteolytic Enzymes, 3rd ed.; Neil, D., Rawlings, G.S., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 1435–1442.

- Spinazzi, M.; De Strooper, B. PARL: The mitochondrial rhomboid protease. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 60, 19–28.

- Petek, E.; Schwarzbraun, T.; Noor, A.; Patel, M.; Nakabayashi, K.; Choufani, S.; Windpassinger, C.; Stamenkovic, M.; Robertson, M.M.; Aschauer, H.N.; et al. Molecular and genomic studies of IMMP2L and mutation screening in autism and Tourette syndrome. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2006, 277, 71–81.

- Petek, E.; Windpassinger, C.; Vincent, J.B.; Cheung, J.; Boright, A.P.; Scherer, S.; Kroisel, P.M.; Wagner, K. Disruption of a Novel Gene (IMMP2L) by a Breakpoint in 7q31 Associated with Tourette Syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001, 68, 848–858.

- Whatley, S.A.; Curti, D.; Marchbanks, R.M. Mitochondrial involvement in schizophrenia and other functional psychoses. Neurochem. Res. 1996, 21, 995–1004.

- Santos, R.; Lefevre, S.D.; Sliwa, D.; Seguin, A.; Camadro, J.-M.; Lesuisse, E. Friedreich Ataxia: Molecular Mechanisms, Redox Considerations, and Therapeutic Opportunities. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010, 13, 651–690.

- Takahashi, Y.; Kubota, M.; Kosaki, R.; Kosaki, K.; Ishiguro, A. A severe form of autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia associated with novel PMPCA variants. Brain Dev. 2021, 43, 464–469.

- Civitarese, A.E.; MacLean, P.; Carling, S.; Kerr-Bayles, L.; McMillan, R.P.; Pierce, A.; Becker, T.C.; Moro, C.; Finlayson, J.; Lefort, N.; et al. Regulation of Skeletal Muscle Oxidative Capacity and Insulin Signaling by the Mitochondrial Rhomboid Protease PARL. Cell Metab. 2010, 11, 412–426.

- Roise, D.; Schatz, G. Mitochondrial presequences. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 4509–4511.

- Roise, D.; Theiler, F.; Horvath, S.J.; Tomich, J.M.; Richards, J.H.; Allison, D.S.; Schatz, G. Amphiphilicity is essential for mitochondrial presequence function. EMBO J. 1988, 7, 649–653.

- Gavel, Y.; Von Heijne, G. Cleavage-site motifs in mitochondrial targeting peptides. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 1990, 4, 33–37.

- Dvořáková-Holá, K.; Matušková, A.; Kubala, M.; Otyepka, M.; Kucera, T.; Večeř, J.; Herman, P.; Parkhomenko, N.; Kutejova, E.; Janata, J. Glycine-Rich Loop of Mitochondrial Processing Peptidase α-Subunit Is Responsible for Substrate Recognition by a Mechanism Analogous to Mitochondrial Receptor Tom20. J. Mol. Biol. 2010, 396, 1197–1210.

- Nagao, Y.; Kitada, S.; Kojima, K.; Toh, H.; Kuhara, S.; Ogishima, T.; Ito, A. Glycine-rich Region of Mitochondrial Processing Peptidase α-Subunit Is Essential for Binding and Cleavage of the Precursor Proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 34552–34556.

- Kučera, T.; Otyepka, M.; Matušková, A.; Samad, A.; Kutejová, E.; Janata, J. A Computational Study of the Glycine-Rich Loop of Mitochondrial Processing Peptidase. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74518.

- Pollock, R.A.; Hartl, F.U.; Cheng, M.Y.; Ostermann, J.; Horwich, A.; Neupert, W. The processing peptidase of yeast mitochondria: The two co-operating components MPP and PEP are structurally related. EMBO J. 1988, 7, 3493–3500.

- Witte, C.; Jensen, R.E.; Yaffe, M.P.; Schatz, G. MAS1, a gene essential for yeast mitochondrial assembly, encodes a subunit of the mitochondrial processing protease. EMBO J. 1988, 7, 1439–1447.

- Lightowlers, R.N.; Taylor, R.W.; Turnbull, D.M. Mutations causing mitochondrial disease: What is new and what challenges remain? Science 2015, 349, 1494–1499.

- Park, C.B.; Larsson, N.-G. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in disease and aging. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 193, 809–818.

- Shoubridge, E.A. Nuclear genetic defects of oxidative phosphorylation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001, 10, 2277–2284.

- Jobling, R.K.; Assoum, M.; Gakh, O.; Blaser, S.; Raiman, J.A.; Mignot, C.; Roze, E.; Durr, A.; Brice, A.; Lévy, N.; et al. PMPCAmutations cause abnormal mitochondrial protein processing in patients with non-progressive cerebellar ataxia. Brain 2015, 138, 1505–1517.

- Choquet, K.; Zurita-Rendón, O.; La Piana, R.; Yang, S.; Dicaire, M.-J.; Boycott, K.M.; Majewski, J.; Shoubridge, E.A.; Brais, B.; Tétreault, M.; et al. Autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia caused by a homozygous mutation in PMPCA. Brain 2015, 139, e19.

- Joshi, M.; Anselm, I.; Shi, J.; Bale, T.A.; Towne, M.; Schmitz-Abe, K.; Crowley, L.; Giani, F.C.; Kazerounian, S.; Markianos, K.; et al. Mutations in the substrate binding glycine-rich loop of the mitochondrial processing peptidase-α protein (PMPCA) cause a severe mitochondrial disease. Mol. Case Stud. 2016, 2, a000786.

- Rubegni, A.; Pasquariello, R.; Dosi, C.; Astrea, G.; Canapicchi, R.; Santorelli, F.M.; Nesti, C. Teaching NeuroImages: Leigh-like features expand the picture of PMPCA-related disorders. Neurologist 2019, 92, e168–e169.

- Vögtle, F.-N.; Brändl, B.; Larson, A.; Pendziwiat, M.; Friederich, M.W.; White, S.M.; Basinger, A.; Kücükköse, C.; Muhle, H.; Jähn, J.A.; et al. Mutations in PMPCB Encoding the Catalytic Subunit of the Mitochondrial Presequence Protease Cause Neurodegeneration in Early Childhood. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 102, 557–573.

- Bertelsen, B.; Melchior, L.; Jensen, L.R.; Groth, C.; Glenthøj, B.; Rizzo, R.; Debes, N.M.; Skov, L.; Brøndum-Nielsen, K.; Paschou, P.; et al. Intragenic deletions affecting two alternative transcripts of the IMMP2L gene in patients with Tourette syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2014, 22, 1283–1289.

- Gimelli, S.; Capra, V.; Di Rocco, M.; Leoni, M.; Mirabelli-Badenier, M.; Schiaffino, M.C.; Fiorio, P.; Cuoco, C.; Gimelli, G.; Tassano, E. Interstitial 7q31.1 copy number variations disrupting IMMP2L gene are associated with a wide spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders. Mol. Cytogenet. 2014, 7, 54.

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zarrei, M.; Tong, W.; Dong, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yang, X.; Macdonald, J.R.; Uddin, M.; et al. Association of IMMP2L deletions with autism spectrum disorder: A trio family study and meta-analysis. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2018, 177, 93–100.

- Elia, J.; Gai, X.; Xie, H.M.; Perin, J.; Geiger, E.; Glessner, J.; D’Arcy, M.; DeBerardinis, R.; Frackelton, E.; Kim, C.; et al. Rare structural variants found in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder are preferentially associated with neurodevelopmental genes. Mol. Psychiatry 2009, 15, 637–646, Corrigendum in Mol. Psychiatry 2010, 15, 637–646.

- Liang, S.; Wang, X.-L.; Zou, M.-Y.; Wang, H.; Zhou, X.; Sun, C.-H.; Xia, W.; Wu, L.-J.; Fujisawa, T.X.; Tomoda, A. Family-based association study of ZNF533, DOCK4 and IMMP2L gene polymorphisms linked to autism in a northeastern Chinese Han population. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2014, 15, 264–271.

- Swaminathan, S.; Shen, L.; Kim, S.; Inlow, M.; West, J.D.; Faber, K.M.; Foroud, T.; Mayeux, R.; Saykin, A.J. Analysis of Copy Number Variation in Alzheimer’s Disease: The NIALOAD/NCRAD Family Study. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2012, 9, 801–814.

- Hsiao, C.-P.; Wang, D.; Kaushal, A.; Saligan, L. Mitochondria-Related Gene Expression Changes Are Associated With Fatigue in Patients With Nonmetastatic Prostate Cancer Receiving External Beam Radiation Therapy. Cancer Nurs. 2013, 36, 189–197.

- Eldomery, M.K.; Akdemir, Z.C.; Vögtle, F.-N.; Charng, W.-L.; Mulica, P.; Rosenfeld, J.A.; Gambin, T.; Gu, S.; Burrage, L.C.; Al Shamsi, A.; et al. MIPEP recessive variants cause a syndrome of left ventricular non-compaction, hypotonia, and infantile death. Genome Med. 2016, 8, 106.

- Pulman, J.; Ruzzenente, B.; Horak, M.; Barcia, G.; Boddaert, N.; Munnich, A.; Rötig, A.; Metodiev, M.D. Variants in the MIPEP gene presenting with complex neurological phenotype without cardiomyopathy, impair OXPHOS protein maturation and lead to a reduced OXPHOS abundance in patient cells. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2021, 134, 267–273.

- Chitrala, K.N.; Hernandez, D.G.; Nalls, M.A.; Mode, N.A.; Zonderman, A.B.; Ezike, N.; Evans, M.K. Race-specific alterations in DNA methylation among middle-aged African Americans and Whites with metabolic syndrome. Epigenetics 2020, 15, 462–482.

- Hatunic, M.; Stapleton, M.; Hand, E.; DeLong, C.; Crowley, V.; Nolan, J. The Leu262Val polymorphism of presenilin associated rhomboid like protein (PARL) is associated with earlier onset of type 2 diabetes and increased urinary microalbumin creatinine ratio in an Irish case–control population. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr. 2009, 83, 316–319.

- Shi, G.; Lee, J.R.; Grimes, D.A.; Racacho, L.; Ye, D.; Yang, H.; Ross, O.A.; Farrer, M.; McQuibban, G.A.; Bulman, D.E. Functional alteration of PARL contributes to mitochondrial dysregulation in Parkinson’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 1966–1974.

- Branda, S.S.; Isaya, G. Prediction and Identification of New Natural Substrates of the Yeast Mitochondrial Intermediate Peptidase. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 27366–27373.

- Burri, L.; Strahm, Y.; Hawkins, C.J.; Gentle, I.E.; Puryer, M.A.; Verhagen, A.; Callus, B.; Vaux, D.; Lithgow, T. Mature DIABLO/Smac Is Produced by the IMP Protease Complex on the Mitochondrial Inner Membrane. Mol. Biol. Cell 2005, 16, 2926–2933.

- Esser, K.; Jan, P.-S.; Pratje, E.; Michaelis, G. The mitochondrial IMP peptidase of yeast: Functional analysis of domains and identification of Gut2 as a new natural substrate. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2004, 271, 616–626.

- Jan, P.-S.; Esser, K.; Pratje, E.; Michaelis, G. Som1, a third component of the yeast mitochondrial inner membrane peptidase complex that contains Imp1 and Imp2. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2000, 263, 483–491.

- Nunnari, J.; Fox, T.D.; Walter, P. A Mitochondrial Protease with Two Catalytic Subunits of Nonoverlapping Specificities. Science 1993, 262, 1997–2004.

- Schneider, A.; Behrens, M.; Scherer, P.; Pratje, E.; Michaelis, G.; Schatz, G. Inner membrane protease I, an enzyme mediating intramitochondrial protein sorting in yeast. EMBO J. 1991, 10, 247–254.

- Schneider, A.; Oppliger, W.; Jenö, P. Purified inner membrane protease I of yeast mitochondria is a heterodimer. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 8635–8638.

- Daum, G.; Gasser, S.; Schatz, G. Import of proteins into mitochondria. Energy-dependent, two-step processing of the intermembrane space enzyme cytochrome b2 by isolated yeast mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 1982, 257, 13075–13080.

- Esser, K.; Pratje, E.; Michaelis, G. SOM 1, a small new gene required for mitochondrial inner membrane peptidase function inSaccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Genet. Genom. 1996, 252, 437–445.

- Girirajan, S.; Brkanac, Z.; Coe, B.P.; Baker, C.; Vives, L.; Vu, T.H.; Shafer, N.; Bernier, R.; Ferrero, G.B.; Silengo, M.; et al. Relative Burden of Large CNVs on a Range of Neurodevelopmental Phenotypes. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002334.

- Goes, F.S.; McGrath, J.A.; Avramopoulos, D.; Wolyniec, P.; Pirooznia, M.; Ruczinski, I.; Nestadt, G.; Kenny, E.E.; Vacic, V.; Peters, I.; et al. Genome-wide association study of schizophrenia in Ashkenazi Jews. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2015, 168, 649–659.

- Isaya, G.; Miklos, D.; A Rollins, R. MIP1, a new yeast gene homologous to the rat mitochondrial intermediate peptidase gene, is required for oxidative metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994, 14, 5603–5616.

- Kalousek, F.; Isaya, G.; Rosenberg, L. Rat liver mitochondrial intermediate peptidase (MIP): Purification and initial characterization. EMBO J. 1992, 11, 2803–2809.

- Chew, A.; Buck, E.A.; Peretz, S.; Sirugo, G.; Rinaldo, P.; Isaya, G. Cloning, Expression, and Chromosomal Assignment of the Human Mitochondrial Intermediate Peptidase Gene (MIPEP). Genomics 1997, 40, 493–496.

- Chew, A.; Sirugob, G.; AlsobrookIIc, J.P.; Isaya, G. Functional and Genomic Analysis of the Human Mitochondrial Intermediate Peptidase, a Putative Protein Partner of Frataxin. Genomics 2000, 65, 104–112.

- Meyers, D.E.; Basha, H.I.; Koenig, M.K. Mitochondrial cardiomyopathy: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Tex. Hear. Inst. J. 2013, 40, 385–394.

- Freeman, M. Rhomboid Proteases and their Biological Functions. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2008, 42, 191–210.

- Voos, W. Chaperone–protease networks in mitochondrial protein homeostasis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1833, 388–399.

- Jeyaraju, D.V.; McBride, H.M.; Hill, R.B.; Pellegrini, L. Structural and mechanistic basis of Parl activity and regulation. Cell Death Differ. 2011, 18, 1531–1539.

- Koonin, E.V. Horizontal gene transfer: The path to maturity. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 50, 725–727.

- Sík, A.; Passer, B.J.; Koonin, E.V.; Pellegrini, L. Self-regulated Cleavage of the Mitochondrial Intramembrane-cleaving Protease PARL Yields Pβ, a Nuclear-targeted Peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 15323–15329.

- Jeyaraju, D.V.; Xu, L.; Letellier, M.-C.; Bandaru, S.; Zunino, R.; Berg, E.A.; McBride, H.M.; Pellegrini, L. Phosphorylation and cleavage of presenilin-associated rhomboid-like protein (PARL) promotes changes in mitochondrial morphology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 18562–18567.

- Lysyk, L.; Brassard, R.; Touret, N.; Lemieux, M.J. PARL Protease: A Glimpse at Intramembrane Proteolysis in the Inner Mitochondrial Membrane. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432, 5052–5062.

- Esser, K.; Tursun, B.; Ingenhoven, M.; Michaelis, G.; Pratje, E. A Novel Two-step Mechanism for Removal of a Mitochondrial Signal Sequence Involves the mAAA Complex and the Putative Rhomboid Protease Pcp1. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 323, 835–843.

- McQuibban, G.A.; Saurya, S.; Freeman, M. Mitochondrial membrane remodelling regulated by a conserved rhomboid protease. Nature 2003, 423, 537–541.

- Saita, S.; Nolte, H.; Fiedler, K.U.; Kashkar, H.; Venne, A.S.; Zahedi, R.; Krüger, M.; Langer, T. PARL mediates Smac proteolytic maturation in mitochondria to promote apoptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 318–328.

- Ishihara, N.; Mihara, K. PARL paves the way to apoptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 263–265.

- Saita, S.; Tatsuta, T.; Lampe, P.A.; König, T.; Ohba, Y.; Langer, T. PARL partitions the lipid transfer protein STARD7 between the cytosol and mitochondria. EMBO J. 2018, 37, e97909.

- Fawcett, K.A.; Wareham, N.J.; Luan, J.; Syddall, H.; Cooper, C.; O’Rahilly, S.; Day, I.N.M.; Sandhu, M.S.; Barroso, I. PARL Leu262Val is not associated with fasting insulin levels in UK populations. Diabetologia 2006, 49, 2649–2652.

- Heinitz, S.; Klein, C.; Djarmati, A. The p.S77N presenilin-associated rhomboid-like protein mutation is not a frequent cause of early-onset Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2011, 26, 2441–2442.

- Wüst, R.; Maurer, B.; Hauser, K.; Woitalla, D.; Sharma, M.; Krüger, R. Mutation analyses and association studies to assess the role of the presenilin-associated rhomboid-like gene in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2016, 39, 217.e13–217.e15.

- Kücükköse, C.; Taskin, A.A.; Marada, A.; Brummer, T.; Dennerlein, S.; Vögtle, F. Functional coupling of presequence processing and degradation in human mitochondria. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 600–613.