Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Agriculture, Dairy & Animal Science

Free-roaming dogs (FRDs) are a worldwide problem, particularly in developing countries. Dogs that are allowed to roam unsupervised cause an array of problems such as vehicle accidents, dog fights, disease transmission, attacks on wildlife, attacks on other domestic animals and humans, uncontrolled reproduction, and the contamination of public areas with fecal matter and garbage.

- free-roaming dogs

- dog population management

- Chile

- responsible dog ownership

1. Introduction

Free-roaming dogs (FRDs) are a worldwide problem, particularly in developing countries [1][2][3][4]. Dogs that are allowed to roam unsupervised cause an array of problems such as vehicle accidents, dog fights, disease transmission, attacks on wildlife, attacks on other domestic animals and humans, uncontrolled reproduction, and the contamination of public areas with fecal matter and garbage [1][2][3][5][6][7].

There are a number of international guidelines from organizations such as the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE, Paris, France) [8] and the International Coalition for Animal Management (ICAM, Cambridge, UK) [9], as well as a number of published articles that offer detailed recommendations for dog population management (DPM) in countries facing the socioeconomic, environmental, political, religious, and human and animal health impacts of FRDs [1][2][3]. The responsibilities of government and non-government organizations (NGOs) are well-delineated in these recommendations and the guidelines provide clear steps towards the formation of advisory groups, pre- and post-data collection, a regulatory framework, and recommendations for a number of program elements, including baseline data collection, to gain a clear appreciation of the local need. This includes a dog population estimate, as well as education, legislation, reproduction control, identification, and registration. These documents also include a monitoring and evaluation framework, as without it there is no ability to measure performance and accountability.

It is important to note that although these guidelines exist, there is no “one size fits all” formula to follow to solve the FRD issue. Countries and communities are all unique and require a tailored approach depending on the local situation. Sadly, many countries spend years investing in DPM programs, resulting in disappointing results, often because the approach is generic or unrelated to the issues in situ or because the execution is scattered and uncoordinated [6].

While FRDs in Chile have been identified as a national, sociocultural, and animal welfare issue for decades [10][11], the release of the responsible pet ownership law and a complementary national pet/companion animal plan has only occurred within the last five years.

Chile, a country in South America with 17,574,003 inhabitants [12], has gained national and international attention over the last few decades because of the various economic, animal welfare, environmental, and social problems caused by FRDs. This is somewhat scandalous because Chile is considered one of South America’s most prosperous nations, with stable long-term economic growth [13]. It is a country known for its beautiful landscapes that are home to endemic wildlife species [14] and whose survival is threatened by dog attacks and/or diseases transmitted by FRDs [15][16][17]. Chile is also a country dependent upon agriculture, with livestock production being one of its main industries [18]. There are almost four million sheep in the country, with 64% of those originating from large herds in Patagonia, while the remainder are from smaller herds of 50 to 500 from the south-central part of the country [19]. For many of these flocks, dog attacks are the number one threat to production and a problem that has driven many small producers out of the industry [20].

Although Chile does not have canine rabies, a host of canine zoonoses [7][21][22] and dog bites [23] have had significant public health impacts. Dogs have also made their mark in online tourism blogs with a surprising number of articles, comments, and stories written by visitors to the country remarking on the astonishing number of dogs seen wandering every city of the country [24][25][26]. While most tourists seem to find the dogs well-fed and friendly, according to studies most Chileans consider FRDs to be a chronic and growing problem in their neighborhoods and communities [27][28].

In 2006, household surveys were done in Chile to evaluate factors influencing the quality of life of the citizens. They found that 50.4% of citizens said that conflicts associated with the presence of free-roaming dogs and cats were the number one problem that should be prioritized in their communities. In 2015, this number had dropped to 48.2%; however, in that same survey, 63% of respondents stated that FRDs constituted a serious or very serious problem. Then, in 2018, the survey was repeated and the majority of respondents said that FRDs and other animals were the most serious problem in their neighborhoods, surpassing even that of crime [29].

2. The Background of the Responsible Pet Ownership Law

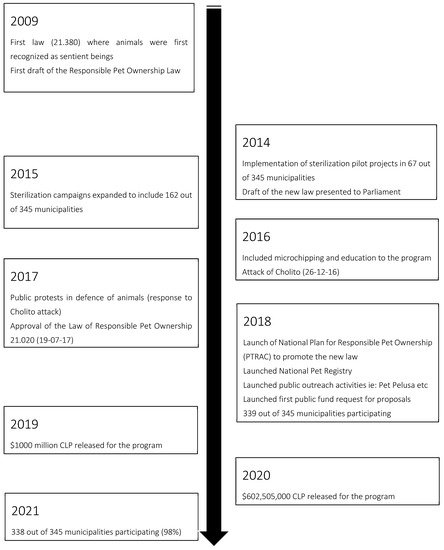

The first draft of the responsible pet ownership bill dates back to 2009 and primarily describes the liability for damages caused by potentially dangerous animals. The bill remained in Congress for years, during which time the scope was amplified to include content related to general pet ownership. In the meantime, in 2014 the government released funds for a pilot sterilization program in 67 (19%) municipalities and then, in 2015, in a further 162 (46.9%) out of a total of 345 municipalities in the country. In 2016, the program expanded to include the microchipping of pets and public outreach about the responsible ownership (RO) of cats and dogs [29]. Then, in December of 2016 while the 2009 bill was still in parliament, the year closed with the brutal attack and presumed death of the now locally famous street dog “Cholito” [30]. The attack occurred in the Patronato neighborhood in the city of Santiago by two individuals with sticks and was filmed by a passerby; the video was subsequently uploaded to the internet, provoking a massive protest by indignant and outraged Chileans demanding that companion animals be offered more protection under the law against abuse, neglect, and mistreatment. The movement termed #justiceforcholito accelerated the promulgation of the Responsible Pet Ownership Law 21.020, also called the “Cholito Law”, which was finally approved in July 2017 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Timeline of important landmark events in the formation and implementation of the National Program for the Responsible Ownership of Companion Animals (PTRAC in Spanish: Programa Tenencia responsible para Animales de Compañía) between 2009 and 2021.

The Cholito Law, or the Responsible Pet Ownership Law (Law 21.020), complements the 2009 “Law on the Protection”of Animals” (Law 20.380) which, although it originally did state that animals are sentient beings and deserving of protection, was deficient in details about how to comply with the law and also continued to consider animals as personal property. The new law (Law 21.020), aims to generate a social and cultural change in the way that citizens interact with companion animals and describes a set of obligations that a person agrees to when he or she decides to keep a pet; that is, to provide it with food, a home, and to treat the pet in an appropriate manner, as well as providing them with veterinary care and not subjecting them to suffering or abandonment in addition to respecting public health and safety regulations [31]. The new legal framework includes three main pillars of action: appropriate animal health care through free municipal-run sterilization campaigns and an increased access to veterinary services; pet identification and registration; and the education of the public about responsible pet ownership.

In 2018, following the release of Law 21.020, the government launched the National Program for Responsible Ownership of Companion Animals (PTRAC in Spanish: Programa Tenencia Responsable para Animales de Compañía), hereafter referred to as PTRAC. Municipalities and NGOs working in the field of veterinary medicine, welfare, and/or responsible pet ownership, and who registered in a National Registry, were permitted to apply for public funds to implement the PTRAC [29]. From 2014 to 2021, CLP 30,193,511,206 (approximately USD 38 million) was allocated to the municipalities [32] to implement PTRAC and 338 of 345 municipalities participated, corresponding to 98% of the total number of districts in the country. Additionally, from 2018 to 2021 inclusively, NGOs have been awarded CLP 2,155,838,605 (approximately USD 3 million) [32] to assist with the implementation of PTRAC. A total of more than 2300 municipal and NGO projects have been financed nationwide.

3. The Overview of the Chilean National Program for the Responsible Ownership of Companion Animals

3.1. Objectives and Indicators

The overarching goal of the PTRAC was centered around the conflict between people, companion animals, and animal welfare. The main objective was to contribute to a better quality of life for all the citizens of Chile by promoting the appropriate coexistence between people and animals, as well as having people live responsibly with companion animals [29]. Many of the specific objectives were detailed in the PTRAC, such as the to improvement of animal health and welfare, increasing animal rights, reducing dog-related public health risks, and increasing RO. However, some of the main program activities, such as the sterilization campaigns which were the backbone of the program, did not have clear goals in communities where they were executed, nor did they have justification for the implementation of the campaigns.

In order to measure the progress of the program and evaluate for success, seven indicators were created that were related to program performance:

-

The average age of sterilizations

-

The percentage of the coverage of animals accessing veterinary services through, exclusively, municipal clinics for the first time

-

The percentage of the coverage of municipalities

-

The rate of change of the number of illnesses that animals present

-

The percentage of municipalities that continued the program after national funding with their own resources

-

The rate of change in the number of infractions of the Responsible Ownership Law

-

The rate of change of dogs that are free-roaming

These indicators, however, have no associated timelines to assess temporal progress or clear indications of what the expected outcome was. While the main goal was to improve the quality of life of the Chilean public, there are no human-related indicators to specifically address this goal; rather, the indicators are focused on indices related to veterinary care, coverage, fines, or the number of FRDs, for example [29].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ani12030228

References

- Taylor, L.H.; Wallace, R.M.; Balaram, D.; Lindenmayer, J.M.; Eckery, D.C.; Mutonono-Watkiss, B.; Parravani, E.; Nel, L.H. The Role of Dog Population Management in Rabies Elimination—A Review of Current Approaches and Future Opportunities. Front. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 109.

- Jackman, J.; Rowan, A. Free-Roaming Dogs in Developing Countries: The Benefits of Capture, Neuter, and Return Programs. In The State of the Animals; Salem, D.J., Rowan, A.N., Eds.; Humane Society Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; pp. 55–78.

- Dalla Villa, P.; Kahn, S.; Stuardo, L.; Iannetti, L.; Di Nardo, A.; Serpell, J.A. Free-Roaming Dog Control among OIE-Member Countries. Prev. Vet. Med. 2010, 97, 58–63.

- Sudarshan, M.K.; Madhusudana, S.N.; Mahendra, B.J.; Rao, N.S.; Narayana, D.A.; Rahman, S.A.; Meslin, F.X.; Lobo, D.; Ravikumar, K. Assessing the burden of human rabies in India: Results of a national multi-center epidemiological survey. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 11, 29–35.

- Acosta-Jamett, G.; Cleaveland, S.; Cunningham, A.A.; Bronsvoort, B.M.D. Demography of Domestic Dogs in Rural and Urban Areas of the Coquimbo Region of Chile and Implications for Disease Transmission. Prev. Vet. Med. 2010, 94, 272–281.

- Barnard, S.; Chincarini, M.; Tommaso, L.; Giulio, F.; Messori, S.; Ferri, N. Free-Roaming Dogs Control Activities in One Italian Province (2000–2013): Is the Implemented Approach Effective? Maced. Vet. Rev. 2015, 38, 149–158.

- Garde, E.; Acosta-Jamett, G.; Bronsvoort, B.M. Review of the Risks of Some Canine Zoonoses from Free-Roaming Dogs in the Post-Disaster Setting of Latin America. Animals 2013, 3, 855–865.

- OIE-World Organisation for Animal Health. Stray Dog Population Control. In OIE-Terrestrial Animal Health Code; OIE: Paris, France, 2010; Chapter 7.7; p. 17. Available online: https://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahc/2018/en_chapitre_aw_stray_dog.htm (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- International Companion Animal Management Coalition. Humane Dog Population Management. 2019. Available online: https://www.icam-coalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/2019-ICAM-DPM-guidance-Interactive-updated-15-Oct-2019.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- Acuña, P. Demografía Canina y Felina En El Gran Santiago 1997. In Veterinary Medicine (Memoria de titulación, Escuela de Ciencias Veterinarias y Pecuarias); Universidad de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 1998.

- Garcia, H. Estimación Demográfica de La Población Canina En La Ciudad de Valdivia. In Veterinary Medicine (Memoria de titulación, Escuela de Medicina Veterinaria); Universidad Austral de Chile: Valdivia, Chile, 1995.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. Síntesis de Resultados Censo, 2017; Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas: Santiago, Chile, 2018; p. 27.

- World, B.; International Finance Corporation, M.I.G.A. The Republic of Chile Systematic Country Diagnostic: Transitioning to a Prosperous Society; Systematic Country Diagnostics; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- Cofre, H.; Marquet, P.A. Conservation Status, Rarity, and Geographic Priorities for Conservation of Chilean Mammals: An Assessment. Biol. Conserv. 1999, 88, 53–68.

- Silva-Rodriguez, E.A.; Sieving, K.E. Influence of Care of Domestic Carnivores on Their Predation on Vertebrates. Conserv. Biol. 2011, 25, 808–815.

- Silva-Rodriguez, E.A.; Verdugo, C.; Aleuy, O.A.; Sanderson, J.G.; Ortega-Solis, G.R.; Osorio-Zuniga, F.; Gonzalez-Acuna, D. Evaluating Mortality Sources for the Pudu (Pudu Puda) in Chile: Implications for the Conservation of a Threatened Deer. Oryx 2009, 44, 97–103.

- Sepúlveda, M.A.; Singer, R.S.; Silva-Rodríguez, E.; Stowhas, P.; Pelican, K. Domestic Dogs in Rural Communities around Protected Areas: Conservation Problem or Conflict Solution? PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86152.

- Panorama de La Agricultura Chilena—2019/Chilean Agriculture Overview. Available online: https://www.odepa.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/panorama2019Final.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Gallo, C.; Tarumán, J.; Larrondo, C. Main Factors Affecting Animal Welfare and Meat Quality in Lambs for Slaughter in Chile. Animals 2018, 8, 165.

- Montecino-Latorre, D.; San Martín, W. Evidence Supporting That Human-Subsidized Free-Ranging Dogs Are the Main Cause of Animal Losses in Small-Scale Farms in Chile. Ambio 2019, 48, 240–250.

- López, J.; Abarca, K.; Cerda, J.; Valenzuela, B.; Lorca, L.; Olea, A.; Aguilera, X. Surveillance System for Infectious Diseases of Pets, Santiago, Chile. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 1674–1676.

- Acosta-Jamett, G.; Cleaveland, S.; Bronsvoort, B.M.; Cunningham, A.A.; Bradshaw, H.; Craig, P.S. Echinococcus Granulosus Infection in Domestic Dogs in Urban and Rural Areas of the Coquimbo Region, North-Central Chile. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 169, 117–122.

- Barrios, C.L.; Bustos-López, C.; Pavletic, C.; Parra, A.; Vidal, M.; Bowen, J.; Fatjó, J. Epidemiology of Dog Bite Incidents in Chile: Factors Related to the Patterns of Human-Dog Relationship. Anim. Open Access J. MDPI 2021, 11, 96.

- Kurdyuk, K. The Plight of Chilean Strays. Chile Today, 2019. Available online: https://chiletoday.cl/the-plight-of-chilean-strays/ (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Mujica, A. Why Chile Has so Many Street Dogs. Chile Today, 2018. Available online: https://www.todayinchile.cl/chile-street-dogs/ (accessed on 11 December 2021).

- Turtle, M. It’s a Dog’s Life. Time Travel Turtle, 2019. Available online: https://www.timetravelturtle.com/street-dogs-santiago-chile/ (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Alejandra Pamela, S.P. Análisis de un Problema Público no Abordado el Caso de los Perros Vagabundos y Callejeros en Chile. Masters’s Thesis, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile, 2013.

- Villatoro, F.J.; Naughton-Treves, L.; Sepúlveda, M.A.; Stowhas, P.; Mardones, F.O.; Silva-Rodríguez, E.A. When Free-Ranging Dogs Threaten Wildlife: Public Attitudes toward Management Strategies in Southern Chile. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 229, 67–75.

- Subsecretaría de Desarrollo Regional y Administrativo (SUBDERE). Ministerio del Interior y Seguridad Pública Informe Final Evaluación Programas Gubernamentales (EPG) Programa Tenence Responsable de Animales de Compañía; Subsecretaría de Desarrollo Regional y Administrativo (SUBDERE): Santiago, Chile, 2019; p. 198.

- Social Media Outcry after the Death of Cholito. My Animals, 2018. Available online: https://myanimals.com/animals/social-media-outcry-death-cholito/ (accessed on 2 January 2021).

- Evens, M.I.V. Las Modificaciones que Introduce la Ley 21.020/2017, de 2 Agosto en el Delito de Maltrato Animal al Código Penal Chileno ¿son Suficientes Para Garantizar la Protección a Los Animales? Masters’s Thesis, Universidad de Valparaíso, Valparaíso, Chile, 2019.

- Martinez Bolzoni, M.E.; (Ministerio del Interior, Subsecretaria de Desarrollo Regional y Administrativo, Santiago, Chile). Subsecretaría de Desarrollo Regional y Administrativo Solicitud de Información 1637 No. AB002T-0002683- Ley No. 20.285 (E9948/2021), 2021.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!