Midlife Black women suffer disproportionately from cardiovascular disease (CVD) and stroke in comparison to White women of similar age and demographic. Risks factors for CVD and stroke are largely considered to be modifiable yet, CVD prevention and awareness campaigns have been less effective among Black women. Decreased awareness of personal CVD risk is associated with delays in the presentation of women to the emergency room or health care providers for symptoms of myocardial infarction. The Midlife Black Women’s Stress and Wellness (B-SWELL) program was co-designed with the community to increase awareness about CVD risk factors, stress, and healthy lifestyle behaviors among midlife Black women.

- women’s health services

- cardiovascular diseases

- community based participatory research

- African American women

1. Introduction

Life’s Simple 7

2. Phase 1

2.1. Partnership and Recruitment

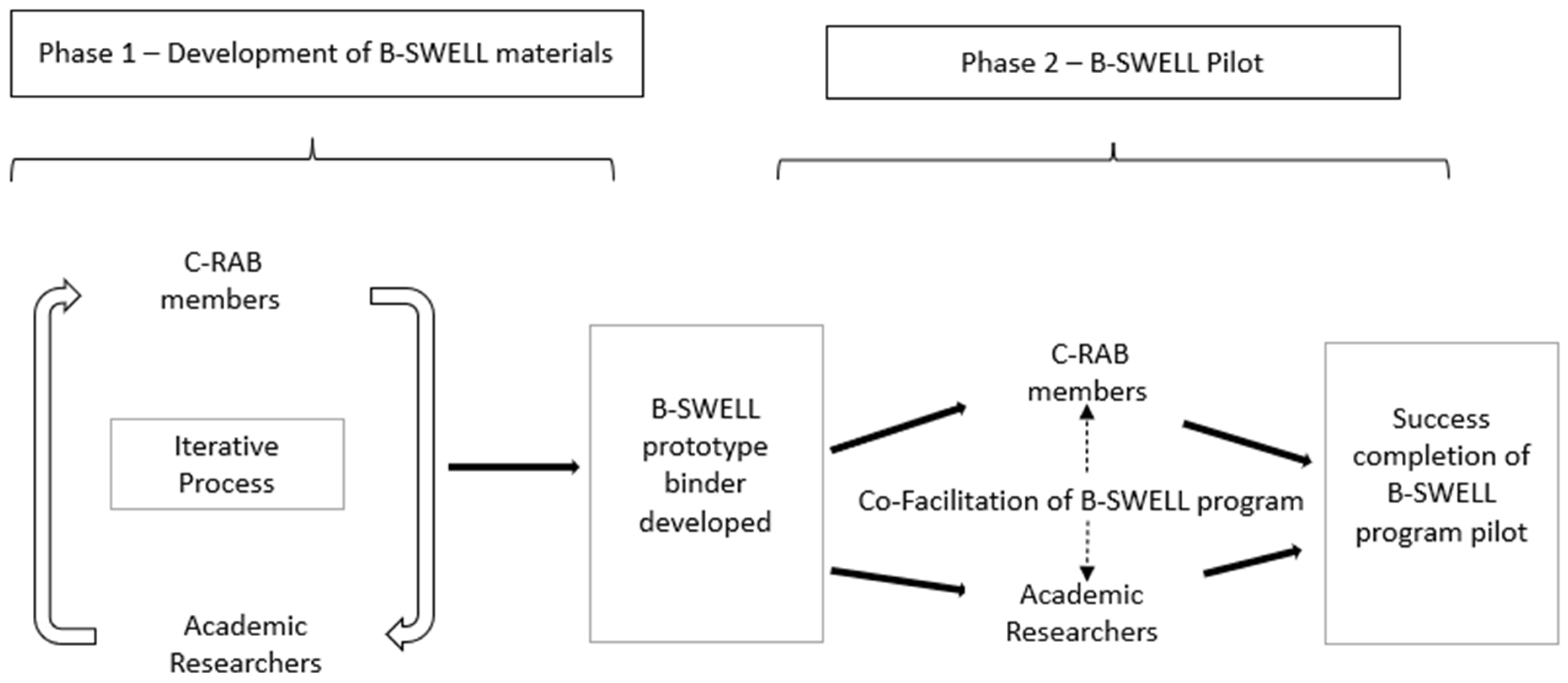

During phase 1, the PI worked closely with a community research advisory board (C-RAB) working group to develop the B-SWELL materials (Figure 1). This iterative process would span one year. In this way, trust was established and the C-RAB members gained familiarity with this study’s purpose and expected outcomes. An initial outline for each module and its content was developed by the principal investigator (PI). Following development, the content was passed along to the C-RAB working group. Each member of the working group reviewed the materials, providing critique and recommendations for improvement or further development. Feedback focused on the informational content of the B-SWELL materials, clarity of the content, and cultural relevancy. Updates were provided intermittently to the larger C-RAB group to solicit feedback and discussion. This cyclical process was successful in the development and refinement of the B-SWELL content and materials.

2.2. B-SWELL Materials

3. Phase 2

B-SWELL Pilot

| Questions for Post-Session Self-Evaluation |

|---|

|

4. Community Participatory Research Methods and Relationship between the PI and the C-RAB

5. Conclusions

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijerph19031356

References

- Williams, R.A. Cardiovascular Disease in African American Women: A Health Care Disparities Issue. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2009, 101, 536–540.

- Thorpe, R.J., Jr.; Wynn, A.J.; Walker, J.L.; Smolen, J.R.; Cary, M.P.; Szanton, S.L.; Whitfield, K.E. Relationship Between Chronic Conditions and Disability in African American Men and Women. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2016, 108, 90–98.

- Mosca, L.; Hammond, G.; Mochari-Greenberger, H.; Towfighi, A.; Albert, M.A. Fifteen-Year Trends in Awareness of Heart Disease in Women: Results of a 2012 American Heart Association National Survey. Circulation 2013, 127, 1254–1263.

- Cushman, M.; Shay, C.M.; Howard, V.J.; Jiménez, M.C.; Lewey, J.; McSweeney, J.C.; Newby, L.K.; Poudel, R.; Reynolds, H.R.; Rexrode, K.M.; et al. Ten-Year Differences in Women’s Awareness Related to Coronary Heart Disease: Results of the 2019 American Heart Association National Survey: A Special Report from The American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e239–e248.

- Robertson, R.M. Women and Cardiovascular Disease: The Risks of Misperception and The Need for Action. Circulation 2001, 103, 2318–2320.

- Bairey Merz, C.N.; Andersen, H.; Sprague, E.; Burns, A.; Keida, M.; Walsh, M.N.; Greenberger, P.; Campbell, S.; Pollin, I.; McCullough, C.; et al. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs Regarding Cardiovascular Disease in Women: The Women’s Heart Alliance. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 123–132.

- Conrad, P.; Barker, K.K. The Social Construction of Illness: Key Insights and Policy Implications. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2010, 51, S67–S79.

- Noonan, A.S.; Velasco-Mondragon, H.E.; Wagner, F.A. Improving the Health of African Americans in the USA: An Overdue Opportunity for Social Justice. Public Health Rev. 2016, 37, 1–20.

- Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Hong, Y.; Labarthe, D.; Mozaffarian, D.; Appel, L.J.; Van Horn, L.; Greenlund, K.; Daniels, S.; Nichol, G.; Tomaselli, G.F.; et al. Defining and Setting National Goals for Cardiovascular Health Promotion and Disease Reduction: The American Heart Association’s Strategic Impact Goal Through 2020 and Beyond. Circulation 2010, 121, 586–613.

- Folsom, A.R.; Shah, A.M.; Lutsey, P.L.; Roetker, N.S.; Alonso, A.; Avery, C.L.; Miedema, M.D.; Konety, S.; Chang, P.P.; Solomon, S.D. American Heart Association’s Life’s Simple 7: Avoiding Heart Failure and Preserving Cardiac Structure and Function. Am. J. Med. 2015, 128, 970–976.

- Kulshreshtha, A.; Vaccarino, V.; Judd, S.E.; Howard, V.J.; McClellan, W.M.; Muntner, P.; Hong, Y.; Safford, M.M.; Goyal, A.; Cushman, M. Life’s Simple 7 and Risk of Incident Stroke: The Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke Study. Stroke 2013, 44, 1909–1914.

- Han, L.; You, D.; Ma, W.; Astell-Burt, T.; Feng, X.; Duan, S.; Qi, L. National Trends in American Heart Association Revised Life’s Simple 7 Metrics Associated with Risk of Mortality Among US Adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1913131.

- Ogunmoroti, O.; Allen, N.B.; Cushman, M.; Michos, E.D.; Rundek, T.; Rana, J.S.; Blankstein, R.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Blaha, M.J.; Veledar, E.; et al. Association between Life’s Simple 7 and Noncardiovascular Disease: The Multi—Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e003954.

- Balazs, C.L.; Morello-Frosch, R. The Three Rs: How Community-Based Participatory Research Strengthens the Rigor, Relevance, and Reach of Science. Environ. Justice 2013, 6, 9–16.

- Kidd, S.A.; Kral, M.J. Practicing Participatory Action Research. J. Couns. Psychol. 2005, 52, 187–195.

- Jones, H.J.; Norwood, C.R.; Bankston, K. Leveraging Community Engagement to Develop Culturally Tailored Stress Management Interventions in Midlife Black Women. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2019, 57, 32–38.

- Baum, F.; MacDougall, C.; Smith, D. Participatory Action Research. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 854–857.