Plant xyloglucan:xyloglucosyl transferases, known as xyloglucan endo-transglycosylases (XETs) are the key players that underlie plant cell wall dynamics and mechanics. These fundamental roles are central for the assembly and modifications of cell walls during embryogenesis, vegetative and reproductive growth, and adaptations to living environments under biotic and abiotic (environmental) stresses. Xyloglucan:xyloglucosyl transferases or xyloglucan endo-transglycosylases (XET), classified under EC 2.4.1.207, transfer the glycosyl groups from one glycoside to another. These enzymes were discovered in 1992 independently in bean epicotyls, nasturtium seeds, and pea, tomato and other plant extracts, and since their discovery, significant knowledge has been accumulated on their mode of action.

- xyloglucosyl transferases

- evolutionary history

- glycoside hydrolase family 16

- mechanism of catalysis

- molecular modelling and dynamics

- transglycosylation reactions

- substrate binding

1. Nomenclatureand classification

2. Catalytic mechanism

3. Structural properties, evolutionary relationships, enzyme activity methods

4. Substrate specificity of transfer reactions with xyloglucan and other than xyloglucan-derived donors and acceptors

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms23031656

References

- Webb, E.C. Enzyme Nomenclature 1992: Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology on the Nomenclature and Classification of Enzymes; Academic Press Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Publishers: San Diego, CA, USA, 1992; ISBN 0-12-227164-5.

- Placzek, S.; Schomburg, I.; Chang, A.; Jeske, L.; Ulbrich, M.; Tillack, J.; Schomburg, D. BRENDA in 2017: New perspectives and new tools in BRENDA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D380–D388.

- Nishitani, K.; Tominaga, R. Endo-xyloglucan transferase, a novel class of glycosyltransferase that catalyzes transfer of a segment of xyloglucan molecule to another xyloglucan molecule. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 21058–21064.

- Farkaš, V.; Sulová, Z.; Stratilová, E.; Hanna, R.; Maclachlan, G. Cleavage of xyloglucan by nasturtium seed xyloglucanase and transglycosylation to xyloglucan subunit oligosaccharides. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1992, 298, 365–370.

- Fry, S.; Smith, R.; Renwick, K.; Martin, D.; Hodge, S.; Matthews, K. Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase, a new wall-loosening enzyme activity from plants. Biochem. J. 1992, 282, 821–828.

- Rose, J.K.C.; Braam, J.; Fry, S.C.; Nishitani, K. The XTH family of enzymes involved in xyloglucan endotransglucosylation and endohydrolysis: Current perspectives and a new unifying nomenclature. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002, 43, 1421–1435.

- Atkinson, R.G.; Johnston, S.L.; Yauk, Y.K.; Sharma, N.N.; Schröder, R. Analysis of xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase (XTH) gene families in kiwifruit and apple. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2009, 51, 149–157.

- Lombard, V.; Golaconda Ramulu, H.; Drula, E.; Coutinho, P.M.; Henrissat, B. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D490–D495.

- CAZypedia Consortium. Ten years of CAZypedia: A living encyclopedia of carbohydrate-active enzymes. Glycobiology 2018, 28, 3–8.

- Viborg, A.H.; Terrapon, N.; Lombard, V.; Michel, G.; Gurvan, M.; Czjzek, M.; Henrissat, B.; Brumer, H. A subfamily roadmap for functional glycogenomics of the evolutionarily diverse Glycoside Hydrolase Family 16 (GH16). J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 15973–15986.

- Eklöf, J.M.; Brumer, H. The XTH gene family: An update on enzyme structure, function, and phylogeny in xyloglucan remodeling. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 456–466.

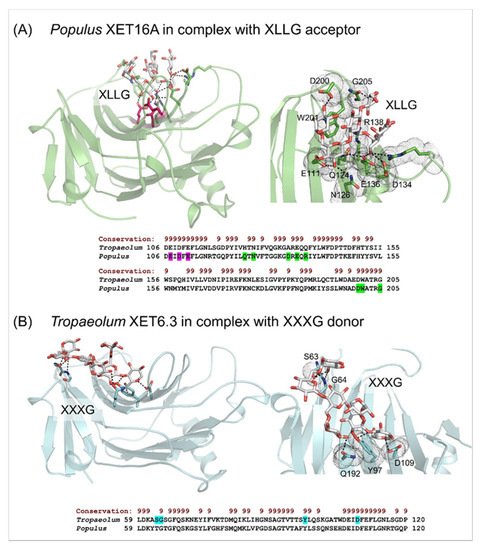

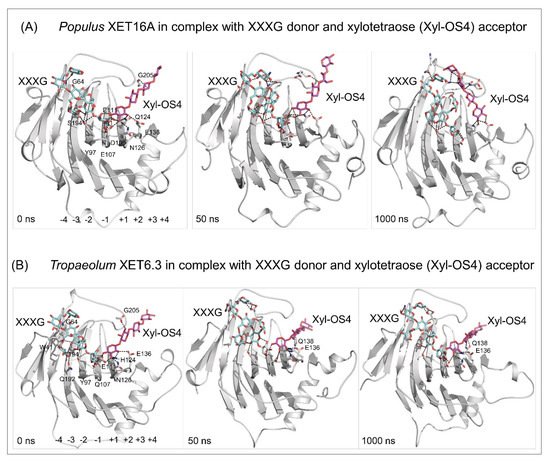

- Mark, P.; Baumann, M.J.; Eklöf, J.M.; Gullfot, F.; Michel, G.; Kallas, A.M.; Teeri, T.T.; Brumer, H.; Czjek, M. Analysis of nasturtium TmNXG1 complexes by crystallography and molecular dynamics provides detailed insight into substrate recognition by family GH16 xyloglucan endo-transglycosylases and endo-hydrolases. Proteins 2009, 75, 820–836.

- Baran, R.; Sulová, Z.; Stratilová, E.; Farkaš, V. Ping-Pong character of nasturtium-seed xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (XET) Reaction. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2000, 19, 427–440.

- Saura-Valls, M.; Faure, R.; Ragas, S.; Piens, K.; Brumer, H.; Teeri, T.T.; Cottaz, S.; Driguez, H.; Planas, A. Kinetic analysis using low-molecular mass xyloglucan oligosaccharides defines the catalytic mechanism of a Populus xyloglucan endotransglycosylase. Biochem. J. 2006, 395, 99–106.

- Hrmova, M.; Farkaš, V.; Lahnstein, J.; Fincher, G.B. A barley xyloglucan xyloglucosyl transferase covalently links xyloglucan, cellulosic substrates, and (1,3;1,4)-β-d-glucans. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 283, 27344.

- Franková, L.; Fry, S.C. Biochemistry and physiological roles of enzymes that ‘cut and paste’ plant cell-wall polysaccharides. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 3519–3550.

- Ait Mohand, F.; Farkaš, V. Screening for hetero-transglycosylating activities in extracts from nasturtium (Tropaeolum majus). Carbohydr. Res. 2006, 34, 577–581.

- Hrmova, M.; Farkaš, V.; Harvey, A.J.; Lahnstein, J.; Wischmann, B.; Kaewthai, N.; Ezcurra, I.; Teeri, T.T.; Fincher, G.B. Substrate specificity and catalytic mechanism of a xyloglucan xyloglucosyl transferase HvXET6 from barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). FEBS J. 2009, 276, 437–456.

- Shinohara, N.; Sunagawa, N.; Tamura, S.; Yokoyama, R.; Ueda, M.; Igarashi, K.; Nishitani, K. The plant cell-wall enzyme AtXTH3 catalyses covalent cross-linking between cellulose and cello-oligosaccharide. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46099.

- Stratilová, B.; Firáková, Z.; Klaudiny, J.; Šesták, S.; Kozmon, S.; Strouhalová, D.; Garajová, S.; Ait-Mohand, F.; Horváthová, Á.; Farkaš, V.; et al. Engineering the acceptor substrate specificity in the xyloglucan endotransglycosylase TmXET6.3 from nasturtium seeds (Tropaeolum majus L.). Plant Mol. Biol. 2019, 100, 181–197.

- Herburger, K.; Franková, L.; Sanhueza, D.; Roig-Sanchez, S.; Meulewaeter, F.; Hudson, A.; Thomson, A.; Laromaine, A.; Budtova, T.; Fry, S.C. Enzymically attaching oligosaccharide-linked ‘cargoes’ to cellulose and other commercial polysaccharides via stable covalent bonds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 4359–4369.

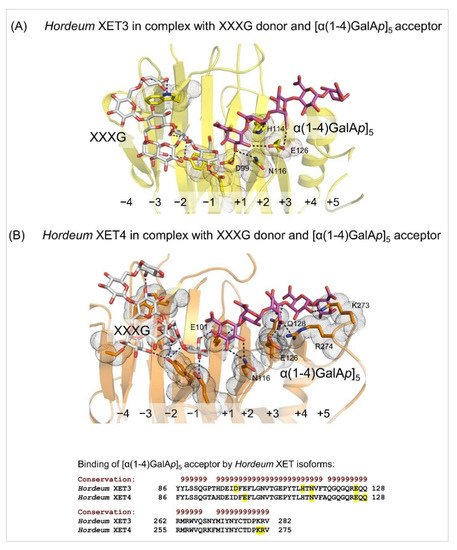

- Stratilová, B.; Šesták, S.; Mravec, J.; Garajová, S.; Pakanová, Z.; Vadinová, K.; Kučerová, D.; Kozmon, S.; Schwerdt, J.G.; Shirley, N.; et al. Another building block in the plant cell wall: Barley xyloglucan xyloglucosyl transferases link covalently xyloglucan and anionic oligosaccharides derived from pectin. Plant J. 2020, 104, 752–767.

- Stratilová, B.; Kozmon, S.; Stratilová, E.; Hrmova, M. Xyloglucan xyloglucosyl transferases and the cell wall structure: Subtle but significant. Molecules 2020, 25, 5619.

- Hrmova, M.; MacGregor, E.A.; Biely, P.; Stewart, R.J.; Fincher, G.B. Substrate binding and catalytic mechanism of a barley β-d-glucosidase/(1,4)-β-d-glucan exohydrolase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 11134–11143.

- Johansson, P.; Brumer, H.; Baumann, M.J.; Kallas, A.M.; Henriksson, H.; Denman, S.E.; Teeri, T.T.T.; Jones, T.A. Crystal structures of a poplar xyloglucan endotransglycosylase reveal details of transglycosylation acceptor binding. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 874–886.

- Hrmova, M.; Fincher, G.B. Barley β-d-glucan exohydrolases. Substrate specificity and kinetic properties. Carbohydr. Res. 1998, 305, 209–221.

- Schröder, R.; Atkinson, R.G.; Redgwell, R.J. Re-interpreting the role of endo-β-mannanases as mannan endotransglycosylase/hydrolases in the plant cell wall. Ann. Bot. 2009, 104, 197–204.

- Franková, L.; Fry, S.C. Phylogenetic variation in glycosidases and glycanases acting on plant cell wall polysaccharides, and the detection of transglycosidase and trans-β-xylanase activities. Plant J. 2011, 67, 662–681.

- Johnston, S.; Prakash, R.; Chen, N.J.; Kumagai, M.H.; Turano, H.M.; Cooney, J.M.; Atkinson, R.G.; Paull, R.E.; Cheetamun, R.; Bacic, A.; et al. An enzyme activity capable of endotransglycosylation of heteroxylan polysaccharides is present in plant primary cell walls. Planta 2013, 237, 173–187.

- Derba-Maceluch, M.; Awano, T.; Takahashi, J.; Lucenius, J.; Ratke, C.; Kontro, I.; Busse-Wicher, M.; Kosik, O.; Tanaka, R.; Winzéll, A.; et al. Suppression of xylan endotransglycosylase PtxtXyn10A affects cellulose microfibril angle in secondary wall in aspen wood. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 666–681.

- Fry, S.C.; Mohler, K.E.; Nesselrode, B.H.W.A.; Franková, L. Mixed-linkage β-glucan:xyloglucan endotransglucosylase, a novel wall-remodelling enzyme from Equisetum (horsetails) and charophytic algae. Plant J. 2008, 55, 240–252.

- Mohler, K.E.; Simmons, T.J.; Fry, S.C. Mixed-linkage glucan:xyloglucan endotransglucosylase (MXE) re-models hemicelluloses in Equisetum shoots but not in barley shoots or Equisetum callus. New Phytol. 2013, 197, 111–122.

- Simmons, T.J.; Mohler, K.E.; Holland, C.; Goubet, F.; Franková, L.; Houston, D.R.; Hudson, A.D.; Meulewaeter, F.; Fry, S.C. Hetero-trans-β-glucanase, an enzyme unique to Equisetum plants, functionalizes cellulose. Plant J. 2015, 83, 753–769.

- Baumann, M.J.; Eklöf, J.M.; Michel, G.; Kallas, A.M.; Teeri, T.T.; Czjzek, M.; Brumer, H. Structural evidence for the evolution of xyloglucanase activity from xyloglucan endo-transglycosylases: Biological implications for cell wall metabolism. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 1947–1963.

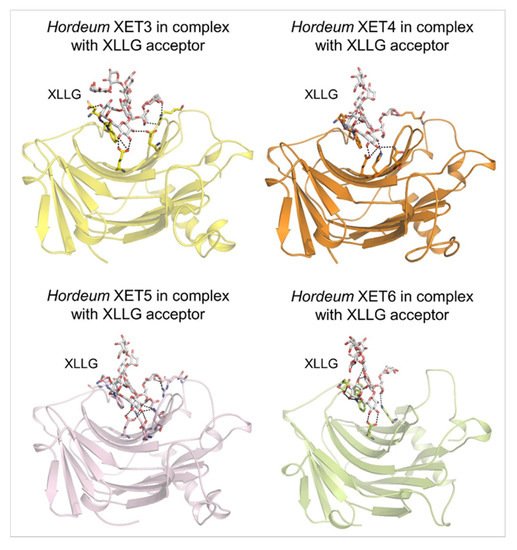

- Vaaje-Kolstad, G.; Farkaš, V.; Fincher, G.B.; Hrmova, M. Barley xyloglucan xyloglucosyl transferases bind xyloglucan-derived oligosaccharides in their acceptor-binding regions in multiple conformational states. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2010, 496, 61–68.

- Eramian, D.; Eswar, N.; Shen, M.; Sali, A. How well can the accuracy of comparative protein structure models be predicted? Prot. Sci. 2008, 17, 1881–1893.

- Pei, J.; Kim, B.-H.; Grishin, N.V. PROMALS3D: A tool for multiple protein sequence and structure alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 2295–2300.

- McGregor, N.; Yin, V.; Tung, C.C.; Van Petegem, F.; Brumer, H. Crystallographic insight into the evolutionary origins of xyloglucan endotransglycosylases and endohydrolases. Plant J. 2017, 89, 651–670.

- Kaewthai, N.; Harvey, A.J.; Hrmova, M.; Brumer, H.; Ezcurra, I.; Teeri, T.T.; Fincher, G.B. Heterologous expression of diverse barley XTH genes in the yeast Pichia pastoris. Plant Biotechnol. 2010, 27, 251–258.

- Behar, H.; Graham, S.W.; Brumer, H. Comprehensive cross-genome survey and phylogeny of glycoside hydrolase family 16 members reveals the evolutionary origin of EG 16 and XTH proteins in plant lineages. Plant J. 2018, 95, 1114–1128.

- Farkaš, V.; Ait-Mohand, F.; Stratilová, E. Sensitive detection of transglycosylating activity of xyloglucan endotransglycosylase/hydrolase (XTH) after isoelectric focusing in polyacrylamide gels. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2005, 43, 431–435.

- Fry, S.C. Novel ‘dot-blot’ assays for glycosyltransferases and glycosylhydrolases: Optimization for xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (XET) activity. Plant J. 1997, 11, 1141–1150.

- Garajová, S.; Flodrová, D.; Ait-Mohand, F.; Farkaš, V.; Stratilová, E. Characterization of two partially purified xyloglucan endotransglycosylases from parsley (Petroselinum crispum) roots. Biologia 2008, 63, 313–319.

- Vaaje-Kolstad, G.; Farkaš, V.; Hrmova, M.; Fincher, G.B. Xyloglucan xyloglucosyl transferases from barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) bind oligomeric and polymeric xyloglucan molecules in their acceptor binding sites. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1800, 674–684.

- Kosík, O.; Garajová, S.; Matulová, M.; Řehulka, P.; Stratilová, E.; Farkaš, V. Effect of the label of oligosaccharide acceptors on the kinetic parameters of nasturtium seed xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (XET). Carbohydr. Res. 2011, 346, 357–361.

- Kosík, O.; Auburn, R.P.; Russell, S.; Stratilová, E.; Garajová, S.; Hrmova, M.; Farkaš, V. Polysaccharide microarrays for high-throughput screening of transglycosylase activities in plant extracts. Glycoconj. J. 2010, 27, 79–87.

- Vissenberg, K.; Martinez-Vilchez, I.M.; Verbelen, J.P.; Miller, J.G.; Fry, S.C. In vivo colocalization of xyloglucan endotransglycosylase activity and its donor substrate in the elongation zone of Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 1229–1237.

- Nishikubo, N.; Awano, T.; Banasiak, A.; Bourquin, V.; Ibatullin, F.; Funada, R.; Brumer, H.; Teeri, T.T.; Hayashi, T.; Sundberg, B.; et al. Xyloglucan endo-transglycosylase (XET) functions in gelatinous layers of tension wood fibers in poplar—a glimpse into the mechanism of the balancing act of trees. Plant Cell Phys. 2007, 48, 843–855.

- Ibatullin, F.M.; Banasiak, A.; Baumann, M.J.; Greffe, L.; Takahashi, J.; Mellerowicz, E.J.; Brumer, H.A. Real-time fluorogenic assay for the visualization of glycoside hydrolase activity in planta. Plant Phys. 2009, 151, 1741–1750.

- Mravec, J.; Kračun, S.K.; Rydahl, M.G.; Westereng, B.; Miart, F.; Clausen, M.H.; Fangel, J.U.; Daugaard, M.; Van Cutsem, P.; De Fine Licht, H.H.; et al. Tracking developmentally regulated post-synthetic processing of homogalacturonan and chitin using reciprocal oligosaccharide probes. Development 2014, 141, 4841–4850.

- Sulová, Z.; Lednická, M.; Farkaš, V. A colorimetric assay for xyloglucan endotransglycosylase from germinating seeds. Anal. Biochem. 1995, 229, 80–85.

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, P.; Li, B.; Huang, S.-Y. HDOCK: A web server for protein-protein and protein-DNA/RNA docking based on a hybrid strategy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W365–W373.

- Morales-Quintana, L.; Carrasco-Orellana, C.; Beltrán, D.; Moya-León, M.A.; Herrera, R. Molecular insights of a xyloglucan endo-transglycosylase/hydrolase of radiata pine (PrXTH1) expressed in response to inclination: Kinetics and computational study. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 136, 155–161.

- Strohmeier, M.; Hrmova, M.; Fischer, M.; Harvey, A.J.; Fincher, J.B.; Pleiss, J. Molecular modeling of family GH16 glycoside hydrolases: Potential roles for xyloglucan transglucosylases/hydrolases in cell wall modification in the Poaceae. Prot. Sci. 2004, 13, 3200–3213.

- Holland, C.; Simmons, T.J.; Meulewaeter, F.; Hudson, A.; Fry, S.C. Three highly acidic Equisetum XTHs differ from hetero-trans-β-glucanase in donor substrate specificity and are predominantly xyloglucan homo-transglucosylases. J. Plant Physiol. 2020, 251, 153210.

- Herburger, K.; Ryan, L.M.; Popper, Z.A.; Holzinger, A. Localisation and substrate specificities of transglycanases in charophyte algae relate to development and morphology. J. Cell Sci. 2018, 131, jcs203208.

- Stratilová, B.; Řehulka, P.; Garajová, S.; Řehulková, H.; Stratilová, E.; Hrmova, M.; Kozmon, S. Structural characterization of the Pet c 1.0201 PR-10 protein isolated from roots of Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Fuss. Phytochemistry 2020, 175, 112368.

- Seven, M.; Derman, Ü.C.; Harvey, A.J. Enzymatic characterization of ancestral/group-IV clade xyloglucan endotransglycosylase/hydrolase enzymes reveals broad substrate specificities. Plant J. 2021, 106, 1060–1073.