Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Cell & Tissue Engineering

Cardiac patch implantation helps maximize the paracrine function of grafted cells and serves as a reservoir of soluble proangiogenic factors required for the neovascularization of infarcted hearts. Researchers have previously fabricated a cardiac patch, EF-HAM, composed of a human amniotic membrane (HAM) coated with aligned PLGA electrospun fibers (EF).

- angiogenesis

- electrospun fiber

- human amniotic membrane

1. Introduction

Skeletal myoblasts are an attractive cell source for cellular cardiomyoplasty because of their autologous availability, high proliferative properties, and high tolerance to ischemia [1]. The transplantation of skeletal myoblasts has demonstrated preclinical and clinical therapeutic benefits in restoring cardiac function after myocardial infarction (MI) [2][3][4]. An increase in ejection fraction, a higher degree of angiogenesis at the infarct site, and reverse ventricular remodeling have been observed in infarcted hearts following myoblast transplantation [2][5][6]. It has been suggested that the improvement in cardiac function observed following myoblast transplantation might be exerted through paracrine properties, rather than the replacement of damaged cardiac muscle with new contractile tissue [1].

Improving the survival of grafted cells helps to maximize the therapeutic paracrine effects of myoblast transplantation. Several strategies have been used to enhance the survival and engraftment efficiency of skeletal myoblasts in infarcted hearts. These strategies include transplantation of myoblast cell sheets or tissue-engineered scaffolds, genetic modification of skeletal myoblasts, and preconditioning of skeletal myoblasts prior to transplantation [7][8][9][10]. As previously reported, intramyocardial myoblast injection may trigger arrhythmic events in patients owing to the failure of skeletal myoblasts to electromechanically couple to the host myocardium, as they remain functionally isolated [11]. The use of myoblast cell sheets or tissue-engineered scaffolds may alleviate the risk of arrhythmia while facilitating cardiac functional recovery through consistent delivery of angiogenic, anti-apoptotic, and antifibrotic cytokines for a longer period of time.

Angiogenesis is indispensable for the recovery of ischemic tissue and is regarded as an effective therapeutic target for cardiac repair and regeneration. It has been reported that vessel ingrowth precedes cardiomyocyte migration during cardiac regeneration, and increased angiogenesis contributes to cardiomyocyte survival and suppresses ventricular remodeling in infarcted hearts [12][13]. Knowing that myoblast-secreted factors could contribute to the functional improvement of infarcted myocardium, cardiac patch seeded with skeletal muscle cells (SkM) could serve as an ideal reservoir of soluble proangiogenic factors for ischemic tissue repair. Therefore, understanding how the interaction between cardiac patch and SkM affects the secretion of proangiogenic factors is crucial for producing tissue-engineered cardiac patch with enhanced angiogenic potential.

2. Physical Characteristics of EF-HAM Scaffolds

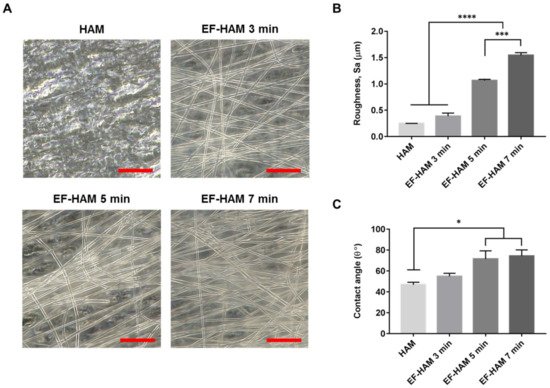

The fabrication of PLGA fibers on decellularized HAM with increasing deposition time produced EF-HAM scaffolds with thicker and denser fiber layers, as illustrated in Figure 1A. The increased deposition of PLGA fibers on HAM also resulted in higher surface roughness and water contact angle of the EF-HAM scaffolds. As shown in Figure 1B,C, EF-HAM 5 min and EF-HAM 7 min scaffolds had significantly rougher and less hydrophilic surfaces compared with HAM owing to the presence of thick PLGA fiber coating.

Figure 1. The gross appearance and characteristics of HAM and EF-HAM scaffolds. (A) PLGA fiber morphology on HAM with varying fiber densities, (B) measurements of surface roughness, and (C) water contact angle of the scaffolds. The values are represented as mean ± SEM (* p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001, or **** p < 0.0001; One-way ANOVA). Scale bar: 20 µm.

3. In Vitro Biocompatibility of EF-HAM Scaffolds

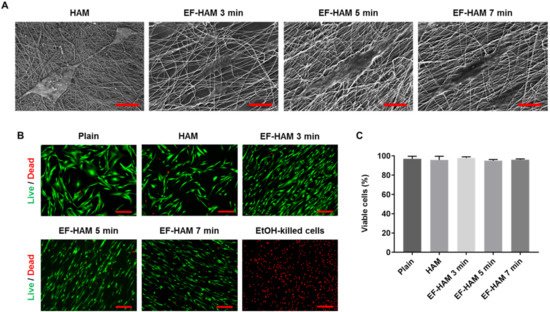

Examination with FESEM revealed that SkM adhered to and spread well on the surface of HAM and all EF-HAM scaffolds (Figure 2A). Cells growing on EF-HAM scaffolds were attached to PLGA fibers and elongated along the alignment of the fibers, whereas cells growing on HAM were attached to the exposed extracellular matrix (ECM) and repopulated the membrane in a random orientation. Live and dead cell analysis confirmed that HAM and all EF-HAM scaffolds were biocompatible and did not exhibit cytotoxic effects against SkM, as the percentage of viable cells in each group was above 95% (Figure 2B,C).

Figure 2. In vitro biocompatibility of HAM and EF-HAM scaffolds with skeletal muscle cells (SkM). (A) Electron micrographs showing good adhesion of SkM on HAM and EF-HAM scaffolds. (B) Live and dead assay images of SkM stained with Calcein AM and EthD-1 and (C) the percentage of viable cells attached to the scaffolds. The values are represented as mean ± SEM (One-way ANOVA). Scale bar: 40 µm, except for HAM (2 µm) (in Figure 2A); 200 µm (in Figure 2B).

4. CM Derived from SkM-Seeded EF-HAM 7 Min Scaffolds Contained Higher Levels of Angiopoietin-1, IL-8, and VEGF-C

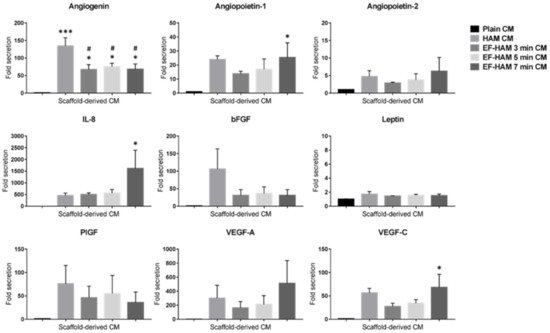

To establish the angiogenic paracrine potential SkM-seeded HAM and EF-HAM scaffolds, CM from each scaffold was collected and subjected to multiplex analysis of proangiogenic factors. Investigation of the angiogenic factors content secreted by SkM-seeded HAM and EF-HAM scaffolds revealed significantly elevated levels of several proangiogenic factors in the HAM and EF-HAM CM compared with those secreted by SkM cultured on the plain surface (plain CM) (Figure 3). The secretion level of angiogenin increased 134.5-fold in HAM CM and from 67.4-fold to 75.6-fold in different EF-HAM CM groups compared with that in plain CM. Angiogenin secretion was significantly higher in the HAM CM group than in all the EF-HAM CM groups. Notably, three specific proangiogenic factors, angiopoietin-1, IL-8, and VEGF-C, were found to be significantly elevated only in EF-HAM 7 min CM compared with plain CM. The fold-secretions of these factors against those in plain CM were 25.4-, 1611.3- and 68.5-fold, respectively. Other angiogenic factors, including angiopoietin-2, bFGF, leptin, PlGF, and VEGF-A, were present in CM derived from SkM-seeded HAM and EF-HAM scaffolds at various degrees of secretion, but the secreted levels were not significantly different when compared with plain CM.

Figure 3. Detection of multiple proangiogenic factors secreted by SkM-seeded HAM and EF-HAM scaffolds. Conditioned medium (CM) from each experimental condition was collected in serum-free culture medium for 72 h before the proangiogenic factors were measured via multiplex analysis. The values are represented as mean ± SEM (* p < 0.05 or *** p < 0.001, compared with plain CM; # p < 0.05, compared with HAM CM; One-way ANOVA).

5. CM Derived from SkM-Seeded EF-HAM Scaffolds Enhanced Endothelial Cell Viability

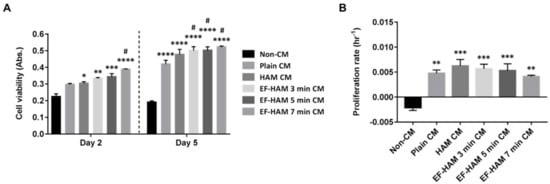

Various coordinated events involving endothelial cell functions are responsible for angiogenesis, including matrix degradation, cell migration, proliferation, and morphogenesis. The angiogenic potential of CM from SkM-seeded HAM and EF-HAM scaffolds was studied by evaluating its influence on the viability of endothelial cells. As shown in Figure 4A, HUVECs subjected to HAM CM and all three different EF-HAM CM had significantly higher cell viability than those in the non-CM control group on the 2nd day of culture. On the 5th day, all CM-treated HUVECs maintained a significantly higher cell viability than non-CM-treated cells. Meanwhile, EF-HAM 7 min CM significantly increased HUVEC viability compared with plain CM as early as the 2nd day, followed by EF-HAM 3 min CM and EF-HAM 5 min CM by the 5th day. As shown in Figure 4B, HUVECs supplemented with CM either from SkM cultured on the plain surface or SkM-seeded HAM and EF-HAM scaffolds all showed increased proliferation compared with those in the non-CM control group, whereby proliferation was negatively influenced by reduced cell viability. Neither HAM CM nor EF-HAM CM induced a higher proliferation rate in HUVECs than plain CM.

Figure 4. HUVECs grown in different EF-HAM CM showed higher viability than those grown in plain CM. (A) HUVEC viability measured using the PrestoBlue assay on the 2nd and 5th days of culture. (B) The proliferation rate of HUVECs was enhanced in the presence of CM. Two-way and one-way ANOVA were performed as shown in Figure 4A,B, respectively, as statistical tests for means and the values are represented as mean ± SEM (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, or **** p < 0.0001, compared with non-CM control; # p < 0.05, compared with plain CM).

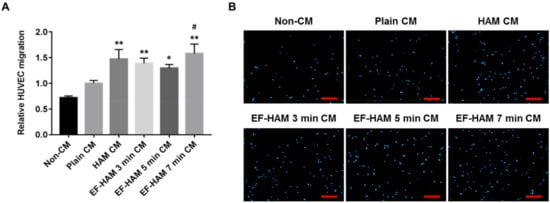

6. CM Derived from SkM-Seeded EF-HAM 7 Min Scaffolds Induced Higher Migration Capacity in HUVECs

A transwell migration assay was conducted to determine whether angiogenic paracrine factors secreted by SkM-seeded HAM and EF-HAM scaffolds could exert a chemotactic response in HUVECs. As shown in Figure 5A,B, CM secreted from HAM and all EF-HAM tissue constructs significantly enhanced the migration capacity of HUVECs relative to that of their non-CM control. Notably, only EF-HAM 7 min CM managed to elicit a higher migratory response in HUVECs at almost 60% greater capacity than plain CM.

Figure 5. EF-HAM 7 min CM induced a higher transwell migration capacity in HUVECs than plain CM. (A) Relative HUVEC migration when co-cultured with SkM-seeded HAM and EF-HAM CM compared with plain CM. (B) Representative images of migrated HUVECs, nuclear-stained with DAPI, at the bottom of transwell inserts. The values are represented as mean ± SEM (* p < 0.05 or ** p < 0.01, compared with non-CM control; # p < 0.05, compared with plain CM; One-way ANOVA). Scale bar: 200 µm.

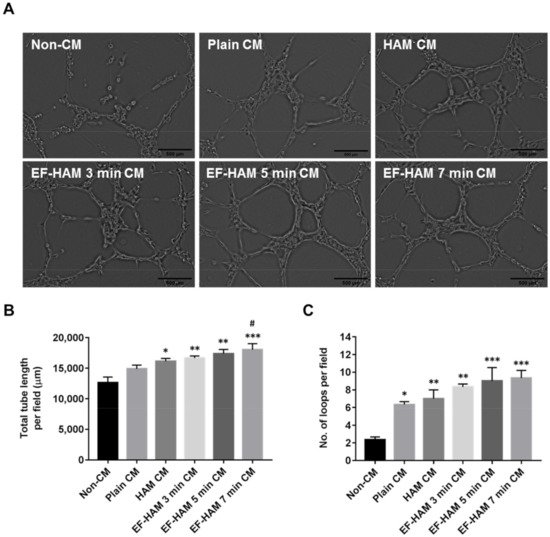

7. EF-HAM 7 Min CM Promoted Longer Tube Formation in HUVECs

To further confirm the angiogenic potential of SkM-seeded HAM and EF-HAM scaffolds, the ability of CM obtained from each scaffold to stimulate tube formation in HUVECs was evaluated using a Matrigel-based assay. Images representing the reorganization of HUVECs into capillary-like structures were recorded and analyzed using an automated tube formation quantification software against several characteristic points and elements of the endothelial cell network (Figure 6A). CM derived from SkM-seeded HAM and all EF-HAM scaffolds significantly enhanced tube formation, as they increased both the total length of tubes and the number of loops compared with the non-CM control (Figure 6B,C). Plain CM also enhanced the number of loops compared with the non-CM control but did not affect the total length of the tubes formed. Notably, only CM secreted by the SkM-seeded EF-HAM 7 min scaffolds was found to significantly increase the total length of tubes formed when compared with plain CM.

Figure 6. EF-HAM 7 min CM induced longer tube formation in HUVECs than plain CM. (A) Formation of capillary-like structures by HUVECs cultured in the presence of CM from different SkM-seeded scaffolds on Matrigel. (B) Total tube length and (C) number of loops per field were quantified to evaluate the proangiogenic effects of CM on endothelial tube formation. The values are represented as mean ± SEM (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, or *** p < 0.001, compared with non-CM control; # p < 0.05, compared with plain CM; One-way ANOVA). Scale bar: 500 µm.

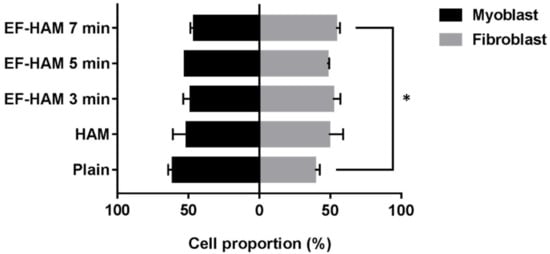

8. SkM-Seeded EF-HAM 7 Min Scaffolds Had a Higher Proportion of Skeletal Fibroblasts

Upon collection of CM from the SkM-seeded HAM and EF-HAM scaffolds, the proportion of skeletal myoblasts and fibroblasts on the scaffolds was evaluated to determine the effect of fibrous scaffold topography on the population of both cells. As illustrated in Figure 7, SkM cultured on EF-HAM 7 min scaffolds displayed a significantly higher proportion of skeletal fibroblasts (54%), whereas a greater proportion of skeletal myoblasts (61%) was observed in the SkM culture on plain surface.

Figure 7. Proportion of skeletal myoblasts and fibroblasts growing on SkM-seeded HAM and EF-HAM scaffolds at the time of CM collection. The values are represented as mean ± SEM (* p < 0.05, compared with plain; One-way ANOVA).

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms23031743

References

- Menasché, P. Skeletal myoblasts and cardiac repair. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2008, 45, 545–553.

- Dib, N.; Dinsmore, J.; Lababidi, Z.; White, B.; Moravec, S.; Campbell, A.; Rosenbaum, A.; Seyedmadani, K.; Jaber, W.A.; Rizenhour, C.S.; et al. One-Year Follow-Up of Feasibility and Safety of the First U.S., Randomized, Controlled Study Using 3-Dimensional Guided Catheter-Based Delivery of Autologous Skeletal Myoblasts for Ischemic Cardiomyopathy (CAuSMIC Study). JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2009, 2, 9–16.

- Povsic, T.J.; O’Connor, C.M.; Henry, T.; Taussig, A.; Kereiakes, D.J.; Fortuin, F.D.; Niederman, A.; Schatz, R.; Spencer, R.; Owens, D.; et al. A double-blind, randomized, controlled, multicenter study to assess the safety and cardiovascular effects of skeletal myoblast implantation by catheter delivery in patients with chronic heart failure after myocardial infarction. Am. Heart J. 2011, 162, 654–662.e1.

- Wang, B.; Zhang, L.; Cao, H.; Yang, J.; Wu, M.; Ma, Y.; Fan, H.; Zhan, Z.; Liu, Z. Myoblast transplantation improves cardiac function after myocardial infarction through attenuating inflammatory responses. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 68780–68794.

- Hagège, A.A.; Marolleau, J.P.; Vilquin, J.T.; Alhéritière, A.; Peyrard, S.; Duboc, D.; Abergel, E.; Messas, E.; Mousseaux, E.; Schwartz, K.; et al. Skeletal myoblast transplantation in ischemic heart failure: Long-term follow-up of the first phase I cohort of patients. Circulation 2006, 114, I108–I113.

- Nakamura, Y.; Asakura, Y.; Piras, B.A.; Hirai, H.; Tastad, C.T.; Verma, M.; Christ, A.J.; Zhang, J.; Yamazaki, T.; Yoshiyama, M.; et al. Increased angiogenesis and improved left ventricular function after transplantation of myoblasts lacking the MyoD gene into infarcted myocardium. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41736.

- Shudo, Y.; Miyagawa, S.; Ohkura, H.; Fukushima, S.; Saito, A.; Shiozaki, M.; Kawaguchi, N.; Matsuura, N.; Shimizu, T.; Okano, T.; et al. Addition of mesenchymal stem cells enhances the therapeutic effects of skeletal myoblast cell-sheet transplantation in a rat ischemic cardiomyopathy model. Tissue Eng. Part A 2014, 20, 728–739.

- Christman, K.L.; Fok, H.H.; Sievers, R.E.; Fang, Q.; Lee, R.J. Fibrin glue alone and skeletal myoblasts in a fibrin scaffold preserve cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Tissue Eng. 2004, 10, 403–409.

- Formigli, L.; Perna, A.M.; Meacci, E.; Cinci, L.; Margheri, M.; Nistri, S.; Tani, A.; Silvertown, J.; Orlandini, G.; Porciani, C.; et al. Paracrine effects of transplanted myoblasts and relaxin on post-infarction heart remodelling. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2007, 11, 1087–1100.

- Niagara, M.I.; Haider, H.K.; Jiang, S.; Ashraf, M. Pharmacologically preconditioned skeletal myoblasts are resistant to oxidative stress and promote angiomyogenesis via release of paracrine factors in the infarcted heart. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 545–555.

- Menasché, P.; Alfieri, O.; Janssens, S.; McKenna, W.; Reichenspurner, H.; Trinquart, L.; Vilquin, J.T.; Marolleau, J.P.; Seymour, B.; Larghero, J.; et al. The Myoblast Autologous Grafting in Ischemic Cardiomyopathy (MAGIC) trial: First randomized placebo-controlled study of myoblast transplantation. Circulation 2008, 117, 1189–1200.

- Ingason, A.B.; Goldstone, A.B.; Paulsen, M.J.; Thakore, A.D.; Truong, V.N.; Edwards, B.B.; Eskandari, A.; Bollig, T.; Steele, A.N.; Woo, Y.J. Angiogenesis precedes cardiomyocyte migration in regenerating mammalian hearts. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018, 155, 1118–1127.e1.

- Kobayashi, K.; Maeda, K.; Takefuji, M.; Kikuchi, R.; Morishita, Y.; Hirashima, M.; Murohara, T. Dynamics of angiogenesis in ischemic areas of the infarcted heart. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7156.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!