Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Engineering, Electrical & Electronic

Optical Fibre Sensors offer a novel and elegant solution to the problem of detection of ultra- low level ethanol concentration in fluids such as biofuels. A wide variety of optical methods exist for accurately determining ethanol concentration, even in the presence of potentially interfering contaminant species. Ethanol has become a key chemical, used in a growing number of modern industrial processes and consumer products. Its accurate measurement is therefore becoming an increasingly significant goal for stakeholders involved in future commercial development as well as academic research.

- ethanol sensing

- optical fibre sensors

- absorption-based sensors

- interferometric sensors

- fibre grating sensors

- plasmonic sensors

1. Introduction

Ethanol is a colourless organic chemical, which is often referred to as alcohol or ethyl alcohol. Its attractive solvent properties of being easily soluble in water and other organic compounds means that it is one of the key chemicals used in modern industrial processes and consumer products. Its uses throughout society are manifold, including as a preservative, an anti-bacterial agent, an astringent in personal care products, as an antidote, an anti-infective and rubbing alcohol in medicines, as a solvent in paints, lacquers and varnishes, as well as an ingredient in intoxicating alcohol beverages and as an additive for flavouring and preserving food [1]. Since the 1970s, interest in the use of ethanol as a renewable fuel or partial substitute for gasoline has grown significantly. It is considered widely as a renewable alternative for fossil-based chemicals such as bioplastics and an additive for ethanol fuel blends [2][3]. In addition, the traditional drinks industry produces ethanol from yeast fermentation in brewing and wine manufacture and the distillation of spirits leads to a huge range of ethanol fortified alcoholic beverages [4].

The proliferation of ethanol uses as described above also increases the demand for its measurement in other sectors such as environmental health and safety, emission control, new biofuel production processes, in pharmaceutical and industrial product development, in breath analysis and in food quality assessment [5]. Analysis of ethanol in many processes is necessarily mandated by the relevant regulating agencies, e.g., the food and drugs administration (FDA) in the USA. A variety of methods can be used to measure the concentration of ethanol in aqueous solution. Commonly used detection methods include enzymatic measurement [6], Raman spectroscopy [7], UV/NIR spectroscopy [8], dichromatic oxidation spectrophotometry [9], refractive index (RI) analysis [8], gas chromatography (GC) [10], high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [11], pycnometry [12], densimetry [12], hydrometry [12], capillary electrophoresis [13] and colorimetric methods [14]. However, the use of these methods has many disadvantages including low reproducibility, potential sample loss, long analysis time, complex offline sample preparation procedures and bulky and expensive instrumentation. Dichromatic oxidation spectrophotometry, pycnometry, hydrometry and densimetry suffer from large sample loss and require a moderate to long time for analysis [9][12][15][16]. The accuracy of the measurement is also highly dependent on the operator’s knowledge and the sample’s temperature [17]. Enzymatic methods are characteristically known for their low accuracy, reproducibility and enzyme stability. Modular Raman spectrometry necessitates precautionary measures for laser use and yield a detection limit of only 1% (v/v) ethanol [18][19]. Complicated calibration procedures are needed for near-infrared spectroscopy and, hence, it can be expensive and time consuming [20]. On the other hand, RI analysis is a relatively simple method, but the accuracy is highly dependent on temperature and can only be used for simple solvents (as opposed to complex mixtures) [21]. When compared to standard chromatography techniques such as GC and HPLC, capillary electrophoresis has lower accuracy. GC is currently considered the most reliable method for ethanol concentration measurement in clinical samples and for alcoholic drinks and is, therefore, the most widely used. Despite the benefits of chromatography techniques, they can be relatively slow (often requiring pre-concentration), complex and costly due to the large quantities of expensive organics needed [22]. Ethanol detection using stimuli-responsive hydrogels and piezoresistive pressure sensors has also been recently reported, where the ethanol concentration of a vodka product (“Wodka Gorbatschow”) with a specified value of 37.5 vol% ethanol was measured [23]. Many industries and research sectors, e.g., alcoholic beverage production and clinical/medical applications, require a simpler, more convenient and higher throughput determination of ethanol concentration [9]. The advantages and disadvantages of the commonly used ethanol detection methods are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of commonly used ethanol measurement techniques.

| Ethanol Measurement Techniques | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic method | Selectivity and sensitivity [6]. | Low accuracy, reproducibility and enzyme stability issues. Non-specific interference [24]. |

| Raman spectroscopy | Specificity and require small sample volume [19]. | Precautionary measures required for laser use and difficulty to measure low concentrations of ethanol [18][19]. |

| UV/NIR spectroscopy | Good sensitivity and less sample preparation. Non-destructive method [8]. |

Complicated calibration procedures, expensive and time consuming [20]. |

| Dichromatic oxidation spectrophotometry | Inexpensive, high accuracy and do not require skilled analysts [25]. | Sample loss and moderate time for analysis. Potassium dichromate oxidation: non-environmentally friendly due to the carcinogenicity of Chromium (Cr) (VI) [26]. |

| Refractive index (RI) analysis | Simple and easy method [21]. | Accuracy highly dependent on temperature and not suitable for complex solvent mixtures [21]. |

| Gas chromatography (GC) | High accuracy and sensitivity [10]. | Expensive instrumentation, laborious and long analysis time [27]. |

| High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) | High accuracy and reproducibility. Less time consuming in comparison to other chromatographic methods [22]. | Expensive, requiring large quantities of expensive organics. Complex to troubleshoot problems [22]. |

| Pycnometry | Simple method [12]. | Long-time analysis, susceptible to error and requires experienced technicians and, hence, is expensive [12]. |

| Densimetry | Rapid, accurate and simple method [12]. | Requires large sample volume and pre-treatment process [20]. |

| Hydrometry | Easy to use and inexpensive [12]. | Requires large amounts of samples and is susceptible to user error [25]. |

| Capillary electrophoresis | Inexpensive and quicker than HPLC [22]. | Low reproducibility issues [28]. Lower accuracy than GC and HPLC [22]. |

| Colorimetric methods | Requires small quantity of sample and is sensitive [29]. | Non-selective and requires pre-distillation of sample [29]. |

| Hydrogel-based and piezoresistive pressure sensors | Low cost, small size and inline process capability [23]. | Measurement uncertainty [23]. |

Recent advances in industrial practice including the emergence of Industry 4.0 for process automation and manufacture has meant that real-time monitoring is a crucial part of those processes. Big data is a major element of the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), which results from the generation and collection of massive data sets from sensors used in diagnosis, process monitoring, product manufacturing, health, safety, and quality control. Bulk optical sensing technology has the unique advantage of being immune to external electromagnetic interference and is potentially highly accurate, specifically in resolving very small changes in RI compared to existing commercially available technologies, but typically requires delicate alignment and coupling mechanisms, which increase sensor size, complexity and reduce stability, e.g., through susceptibility to mechanical vibration. On the other hand, optical sensors based on optical fibres are becoming a highly versatile, rugged and potentially cost-effective alternative due to their capability for being miniaturised, readily integrated with electro-optical components or electronic systems, feasible for real-time and remote sensing, and light weight, as well as having a minimised need for precise alignment and coupling [30][31].

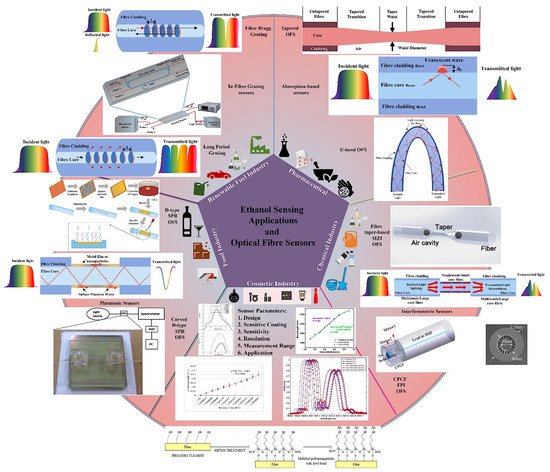

Optical fibres have been investigated for their potential use in sensing applications since the early 1980s, and several advances have been made in the fields of optical fibre chemical sensing and biosensing [32]. At that time, researchers also started exploring the concept of optical fibre-based ethanol sensors [33][34]. Wolfbies et al. (1988) used enzymatic oxidation of ethanol to create an optical fibre ethanol biosensor [34]. The sensor layer included an oxygen-sensitive fluorescing indicator that detected a drop in local oxygen partial pressure due to enzymatic oxidation. The sensor detected ethanol concentrations in the range of 50 to 500 mmol L−1, with an accuracy of ±4 mmol L−1 at 100 mmol L−1. Since then, a diverse range of mechanisms have been investigated for measuring ethanol concentration using optical fibre sensors and, in some cases, real applications have been further explored using these sensing schemes. In general, these sensors have delivered encouraging results and demonstrated great potential for ethanol sensing in a wide range of applications. Figure 1 is a graphical summary of a selection of applications for ethanol sensing and optical fibre sensing schemes utilised for ethanol sensing extracted from recent literature [35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43] and includes sensor design parameters and typical output responses. Several articles have recently outlined and reflected on the advancement of optical fibre chemical and biosensors from various perspectives [31][32][44][45][46][47][48]. There are abundant possibilities and potential for fabricating highly effective optical fibre ethanol sensors in view of the rapid development of this technology and related functional materials [31]. A comparison of their respective performance is provided, which points to their applicability for use in current and future full-scale industrial measurement systems. The continuously developing needs of real time measurement and the emergence of the internet of things (IoT) sets the background to this article, which is intended to inspire and focus further research and wider utilization of these sensors in the commercially significant industrial and medical sectors.

Figure 1. Optical fibre ethanol sensing schemes, applications of ethanol sensing and sensor parameters. Some data extracted from Refs. [35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43].

2. Current Status and Future Prospects of Optical Fibre Ethanol Sensors

Clearly, a broad variety of optical fibre ethanol sensors, based on unique structural configurations and sensitive coatings, have been reported and their efficacy has been verified experimentally in the literature. Fluorescence-based optical fibre sensors have also been reported in limited cases, including [34][49][50]. Recent developments in whispering gallery mode type sensors have also been reported for ethanol measurement in aqueous solutions for which resonant modes are supported and the light signal circulates in a dielectric ring or microbubble. The supported modes form the ‘whispering gallery’ modes, leading to an enhanced light interaction length in the surrounding medium of the bubble or ring, which facilitates high-sensitivity ethanol concentration measurement [51][52][53][54]. Although the WGM sensors are a relatively recent development and have shown great promise in terms of enhanced sensitivity, their widespread use in industrial measurement is limited by the fact that the sharp (high Q) spectral resonance peak needs to be monitored using a high-resolution OSA or similar instrument.

The diversity of sensor designs and configurations of optical fibre ethanol sensors is summarised in Table 2 and includes a summary of the advantages and disadvantages of the four main sensor categories considered in this entry.

Table 2. Summary of advantages and disadvantages of four main categories of optical fibre ethanol sensors.

| Sensor Type | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Absorption-based sensors | Easy, simple, versatile and low-cost design. Ease of implementation. Reproducibility. |

Fragility due to deformation of fibre. Low selectivity without a sensitive film. |

| Interferometric sensors | Robust and easily implemented. Multimode Interferometers: Easy design, flexible structure and reproducible. Sensitive. |

Costly, precise and delicate design procedures for most interferometric techniques. Multimode Interferometers: non-periodic spectrum and, hence, difficult signal demodulation. Hydrogel-based FPI: difficult reproducibility. |

| Fibre grating sensors | Adjustable structure design. FBG and LPG: When combined, can be used for simultaneous temperature and RI measurement. |

Require expensive interrogation systems. FBG: Fragile due to fibre etching for RI measurements and temperature crosstalk. LPG: Complicated signal demodulation. |

| Plasmonic sensors | Accuracy. High sensitivity. |

High processing requirements in terms of uniformity and thickness consistency of metal coating. |

It is clear that optical fibre ethanol sensors have undergone remarkable development in recent decades in terms of sensing performance, robust design and miniaturization. A number of optical fibre sensors have shown great potential for ethanol concentration measurement in a wide range of real-world applications. This is based primarily on their characteristics, including potential low fabrication cost, small size, design flexibility, immunity to external electromagnetic interference and capability for long-distance sensing (from the point of measurement). Current research is mainly focused on making compact and flexible sensor structures using the wide range of different designs and available fibres as well as continuously striving to improve sensing performance using various sensitive materials such as novel 2D materials, new metal nano-films and nanoparticles and deformation (e.g., etching or tapering) of the fibre. However, this can often make sensor processing and fabrication complex and, in some cases, compromises the mechanical strength required for many industrial applications. Maintaining the uniformity and thickness of metal films and other coatings requires accurate processing with excellent repeatability. The repeatability is particularly significant in cases where novel 2D materials are used in combination with metal coatings to improve sensitivity. The coating process is often necessarily complex to achieve better contact between the metal and a functionalised sensitive layer. Cross-sensitivity to temperature and other chemicals in solutions containing ethanol is also a matter of concern as it can affect the selectivity and accuracy. Based on current developments and the perceived requirements of industrial applications, particularly with the arrival of Industry 4.0 and its relation to the burgeoning developments in the context of IoT, the following have been identified as significant future directions for research in optical fibre-based ethanol concentration sensors:

-

Targeting specific applications is crucial in bringing the technology to a real-world implementation. Being a good target analyte, it is necessary to explore and realise the application-specific requirements where ethanol concentration measurement is an important parameter, e.g., in biofuel production and processing, general fuel monitoring, the food and beverage industry, the paints and varnishes industry, medical diagnostics, and in the cosmetics industry. A specific example is evident in the case of bio-ethanol production using biomasses, specifically algae. There are very stringent requirements for specific sensitivity and resolution attainment, temperature stability and selectivity for sensing purposes as well as the ability to operate in real-time, which are crucial to avoiding sample loss and long lead time offline analysis [41][55]. It is clear that optical fibre sensors have a significant role to play in providing solutions in this scenario.

-

In many cases of industrial production and/or processing, high-sensitivity/ultra-low-level ethanol sensing is a fundamental requirement. Hence, many researchers have focused on improving the sensitivity of optical fibre ethanol sensors by seeking improvements in materials, coatings as well as sensor structures. However, temperature cross-sensitivity and/or cross-sensitivity caused by other chemical species in the measurand solution are also significant issues. Some researchers have formulated techniques to mitigate temperature cross-sensitivity, including an inline C-shaped open-cavity FPI [56], a combination of FP cavity and Michelson interferometry [57], micro grooved FBG [42], a combination of FBG and LPG for simultaneous temperature and RI measurement [37] and etched FBGs [58]. Cross-sensitivity due to other chemicals can be minimised or avoided by improving the selectivity of sensors and some work has also been reported for improving selectivity by modifying POF with CNTs [59], by combining interferometric and LSPR techniques [60] and by using ethanol-selective enzymes [61]. However, these sensor systems exhibit other drawbacks such as the use of specialised essential non-commercial parts, complex interrogation methods, low mechanical strength, narrow measurement range and limited sample-by-sample measurement. It is important to state here that some of those drawbacks may be irrelevant for some applications, depending on their specific requirements. Therefore, future research is likely to be focused on achieving high sensitivity combined with high selectivity and temperature compensation of optical fibre ethanol sensors.

-

Reusability of optical fibre ethanol sensors, specifically when they are coated with novel 2D materials and/or precious metals, is becoming increasingly important. In the case of SPR chemical sensors, some reusability techniques are explored such as removing the immobilised histidine-tagged peptide (HP) layer using imidazole (IM) on Ni metal to regenerate the sensor surface [62], by cutting and polishing the sensor tip to regenerate the surface [63] and by exposing the sensor to ethanol for repeated cycles [64] to demonstrate the reproducibility of results.

-

Distributed optical fibre sensing techniques for industrial measurement have gained significant attention during the last 10 years, which has culminated in many commercial systems becoming available (e.g., Luna [65] and OZ Optics [66]). Distributed optical fibre sensors are currently being used in several industrial applications, e.g., in oil and gas exploration, and in large structure monitoring. This technology certainly has scope for future measurements covering large scale ethanol industrial production and other chemical processing applications [67]. However, interrogation of distributed optical fibre sensors is complex and the instrumentation is currently expensive. Consequently, their uses are currently confined to a few ‘high end’ applications, e.g., where very large numbers of sensing points are required and non-optical measurement is not feasible. Research in this direction in combination with real-time, robust, sensitive and selective optical fibre ethanol sensing can help realise the Industry 4.0 requirements of real-time sensing and data collection to develop a digital twin of the facilities to predict yield and future demands of ethanol in industrial production and processing.

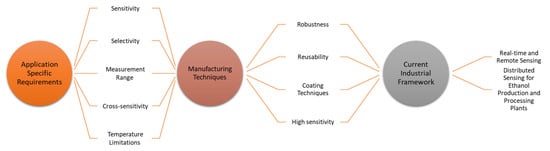

All these future directions and requirements of optical fibre ethanol sensors in the current industrial framework are interconnected. Knowing specific application needs can enhance the understanding of optical fibre ethanol sensor manufacturing techniques such as specific requirements for sensitivity, robustness, reusability, temperature limitations and coating materials and, hence, the industrial requirements for real time and remote sensing. Figure 2 explains the interconnection between the application requirements, sensor design, manufacturing techniques and the current industrial framework.

Figure 2. Interconnection of application-specific requirements, manufacturing techniques and the current industrial framework.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/s22030950

References

- Ethanol Uses, Benefits, and Chemical Safety Facts. Available online: https://www.chemicalsafetyfacts.org/ethanol/ (accessed on 25 April 2021).

- Ethanol Explained-U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Available online: https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/biofuels/ethanol.php (accessed on 25 April 2021).

- Beverage & Industrial Use-EPURE. Available online: https://www.epure.org/about-ethanol/beverage-industrial-use/ (accessed on 25 April 2021).

- Onuki, S.; Koziel, J.A.; Jenks, W.S.; Cai, L.; Grewell, D.; van Leeuwen, J.H. Taking Ethanol Quality beyond Fuel Grade: A Review. J. Inst. Brew. 2016, 122, 588–598.

- Tharsika, T.; Thanihaichelvan, M.; Haseeb, A.S.M.A.; Akbar, S.A. Highly Sensitive and Selective Ethanol Sensor Based on ZnO Nanorod on SnO2 Thin Film Fabricated by Spray Pyrolysis. Front. Mater. 2019, 6, 122.

- Fernanbes, E.N.; Reis, B.F. Automatic Flow Procedure for the Determination of Ethanol in Wine Exploiting Multicommutation and Enzymatic Reaction with Detection by Chemiluminescence. J. AOAC Int. 2004, 87, 920–926.

- Numata, Y.; Shinohara, Y.; Tanaka, H. Quantitative Analysis of Ethanol–Methanol–Water Ternary Solutions Using Raman Spectroscopy. Spectrosc. Lett. 2019, 52, 306–311.

- Castritius, S.; Kron, A.; Schäfer, T.; Rädle, M.; Harms, D. Determination of Alcohol and Extract Concentration in Beer Samples Using a Combined Method of Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy and Refractometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 12634–12641.

- Seo, H.B.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, O.K.; Ha, J.H.; Lee, H.Y.; Jung, K.H. Measurement of Ethanol Concentration Using Solvent Extraction and Dichromate Oxidation and Its Application to Bioethanol Production Process. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 36, 285–292.

- Weatherly, C.A.; Woods, R.M.; Armstrong, D.W. Rapid Analysis of Ethanol and Water in Commercial Products Using Ionic Liquid Capillary Gas Chromatography with Thermal Conductivity Detection and/or Barrier Discharge Ionization Detection. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 1832–1838.

- Castellari, M.; Sartini, E.; Spinabelli, U.; Riponi, C.; Galassi, S. Determination of Carboxylic Acids, Carbohydrates, Glycerol, Ethanol, and 5-HMF in Beer by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography and UV-Refractive Index Double Detection. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2001, 39, 235–238.

- Brereton, P.; Hasnip, S.; Bertrand, A.; Wittkowski, R.; Guillou, C. Analytical Methods for the Determination of Spirit Drinks. TrAC-Trends Anal. Chem. 2003, 22, 19–25.

- Collins, T.S.; Miller, C.A.; Altria, K.D.; Waterhouse, A.L. Development of a Rapid Method for the Analysis of Ethanol in Wines Using Capillary Electrophoresis. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1997, 48, 280–284.

- Sumbhate, S.; Sumbhate, S.V.; Nayak, S.; Goupale, D.; Tiwari, A.; Jadon, R.S. Colorimetric Method for the Estimation of Ethanol in Alcoholic-Drinks. J. Anal. Tech. 2012, 1, 1–6.

- Bennett, C. Spectrophotometric Acid Dichromate Method for the Determination of Ethyl Alcohol. Am. J. Med. Technol. 1971, 37, 217–220.

- Pilone, G. Determination of Ethanol in Wine by Titrimetric and Spectrophotometric Dichromate Method: Collaborative Study. J Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem. 1985, 68, 188–190.

- Osorio, D.; Pérez-Correa, J.R.; Agosin, E.; Cabrera, M. Soft-Sensor for on-Line Estimation of Ethanol Concentrations in Wine Stills. J. Food Eng. 2008, 87, 571–577.

- Sanford, C.L.; Mantooth, B.A.; Jones, B.T. Determination of Ethanol in Alcohol Samples Using a Modular Raman Spectrometer. J. Chem. Educ. 2001, 78, 1221–1225.

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Raman Spectroscopy-Romanian Database of Raman Spectroscopy. Available online: http://www.rdrs.ro/blog/articles/advantages-disadvantages-raman-spectroscopy/ (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Wang, M.L.; Choong, Y.M.; Su, N.W.; Lee, M.H. A Rapid Method for Determination of Ethanol in Alcoholic Beverages Using Capillary Gas Chromatography. J. Food Drug Anal. 2003, 11, 133–140.

- Gerogiannaki-Christopoulou, M.; Kyriakidis, N.v.; Athanasopoulos, P.E. New Refractive Index Method for Measurement of Alcoholic Strength of Small Volume Samples. J. AOAC Int. 2003, 86, 1232–1235.

- Disadvantages & Advantages of an HPLC. Available online: https://sciencing.com/disadvantages-advantages-hplc-5911530.html (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Erfkamp, J.; Guenther, M.; Gerlach, G. Hydrogel-Based Sensors for Ethanol Detection in Alcoholic Beverages. Sensors 2019, 19, 1199.

- Dasgupta, A. Methods of Alcohol Measurement. In Alcohol, Drugs, Genes and the Clinical Laboratory; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 155–166. ISBN 978-0-12-805455-0.

- Sriariyanun, M.; Mutrakulcharoen, P.; Tepaamorndech, S.; Cheenkachorn, K.; Rattanaporn, K. A Rapid Spectrophotometric Method for Quantitative Determination of Ethanol in Fermentation Products. Orient. J. Chem. 2019, 35, 744–750.

- Zhang, P.; Hai, H.; Sun, D.; Yuan, W.; Liu, W.; Ding, R.; Teng, M.; Ma, L.; Tian, J.; Chen, C. A High Throughput Method for Total Alcohol Determination in Fermentation Broths. BMC Biotechnol. 2019, 19, 30.

- Kuswandi, B.; Irmawati, T.; Hidayat, M.A.; Jayus; Ahmad, M. A Simple Visual Ethanol Biosensor Based on Alcohol Oxidase Immobilized onto Polyaniline Film for Halal Verification of Fermented Beverage Samples. Sensors 2014, 14, 2135–2149.

- Nowak, P.M.; Woźniakiewicz, M.; Gładysz, M.; Janus, M.; Kościelniak, P. Improving Repeatability of Capillary Electrophoresis—a Critical Comparison of Ten Different Capillary Inner Surfaces and Three Criteria of Peak Identification. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 4383–4393.

- Magrı´, A.D.; Magrı´fabrizio, A.L.; Balestrieri, M.; Sacchini, A.; Marini, D. Spectrophotometric Micro-Method for the Determination of Ethanol in Commercial Beverages. Fresenius J. Anal. Chem. 1997, 357, 985–988.

- Zhang, Y.N.; Sun, Y.; Cai, L.; Gao, Y.; Cai, Y. Optical Fiber Sensors for Measurement of Heavy Metal Ion Concentration: A Review. Measurement 2020, 158, 107742.

- Yin, M.J.; Gu, B.; An, Q.F.; Yang, C.; Guan, Y.L.; Yong, K.T. Recent Development of Fiber-Optic Chemical Sensors and Biosensors: Mechanisms, Materials, Micro/Nano-Fabrications and Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 376, 348–392.

- McDonagh, C.; Burke, C.S.; MacCraith, B.D. Optical Chemical Sensors. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 400–422.

- Walters, B.S.; Nielsen, T.J.; Arnold, M.A. Fiber-Optic Biosensor for Ethanol, Based on an Internal Enzyme Concept. Talanta 1988, 35, 151–155.

- Wolfbeis, O.S.; Posch, H.E. A Fibre Optic Ethanol Biosensor. Fresenius Z. Anal. Chem. 1988, 332, 255–257.

- Girei, S.H.; Shabaneh, A.A.; Arasu, P.T.; Painam, S.; Yaacob, M.H. Tapered Multimode Fiber Sensor for Ethanol Sensing Application. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 4th International Conference on Photonics (ICP), Melaka, Malaysia, 28–30 October 2013; pp. 275–277.

- Tian, J.; Quan, M.; Jiao, Y.; Yao, Y.; Liang, W.; Huang, Y.Y.; Xu, Y.; Lee, R.K.; Yariv, A. Fast Response Fabry-Perot Interferometer Microfluidic Refractive Index Fiber Sensor Based on Concave-Core Photonic Crystal Fiber. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 20132–20142.

- Monteiro-Silva, F.; Santos, J.L.; Manuel, J.; Martins De Almeida, M.; Coelho, L. Quantification of Ethanol Concentration in Gasoline Using Cuprous Oxide Coated Long Period Fiber Gratings. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 1493–1500.

- Sun, Y.-S.; Li, C.-J.; Hsu, J.-C. Integration of Curved D-Type Optical Fiber Sensor with Microfluidic Chip. Sensors 2016, 17, 63.

- Xi, X.; Xu, J.; Li, S.; Song, J.; Yang, W.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, S.; Han, Y.; Fan, X. An Au Nanofilm-Graphene/D-Type Fiber Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor for Highly Sensitive Specificity Bioanalysis. Sensors 2020, 20, 991.

- Zhang, Q.; Xue, C.; Yuan, Y.; Lee, J.; Sun, D.; Xiong, J. Fiber Surface Modification Technology for Fiber-Optic Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensors. Sensors 2012, 12, 2729–2741.

- Memon, S.F.; Ali, M.M.; Pembroke, J.T.; Chowdhry, B.S.; Lewis, E. Measurement of Ultralow Level Bioethanol Concentration for Production Using Evanescent Wave Based Optical Fiber Sensor. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2018, 67, 780–788.

- Alemohammad, H.; Toyserkani, E.; Pinkerton, A.J. Femtosecond Laser Micromachining of Fibre Bragg Gratings for Simultaneous Measurement of Temperature and Concentration of Liquids. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2008, 41, 185101.

- Liao, C.; Zhu, F.; Zhou, P.; Wang, Y.; Kong, H. Fiber Taper-Based Mach-Zehnder Interferometer for Ethanol Concentration Measurement. Micromachines 2019, 10, 741.

- Wang, X.D.; Wolfbeis, O.S. Fiber-Optic Chemical Sensors and Biosensors (2013–2015). Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 203–227.

- Wolfbeis, O.S. Fiber-Optic Chemical Sensors and Biosensors. Anal. Chem. 2004, 76, 3269–3284.

- Wolfbeis, O.S. Fiber-Optic Chemical Sensors and Biosensors. Anal. Chem. 2002, 74, 2663–2677.

- Wang, X.D.; Wolfbeis, O.S. Fiber-Optic Chemical Sensors and Biosensors (2008–2012). Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 487–508.

- Wang, X.D.; Wolfbeis, O.S. Fiber-Optic Chemical Sensors and Biosensors (2015–2019). Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 397–430.

- Orellana, G.; Gomez-Carneros, A.M.; de Dios, C.; Garcia-Martinez, A.A.; Moreno-Bondi, M.C. Reversible Fiber-Optic Fluorosensing of Lower Alcohols. Anal. Chem. 2002, 67, 2231–2238.

- Schartner, E.P.; Tsiminis, G.; Henderson, M.R.; Warren-Smith, S.C.; Monro, T.M. Quantification of the Fluorescence Sensing Performance of Microstructured Optical Fibers Compared to Multi-Mode Fiber Tips. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 18541–18550.

- Saetchnikov, V.A.; Tcherniavskaia, E.A.; Schweiger, G. Development of Optical Micro Resonance Based Sensor for Detection and Identification of Microparticles and Biological Agents. Photonic Mater. Devices Appl. III 2009, 7366, 73661L.

- Berneschi, S.; Farnesi, D.; Cosi, F.; Conti, G.N.; Pelli, S.; Righini, G.C.; Soria, S. High Q Silica Microbubble Resonators Fabricated by Arc Discharge. Opt. Lett. 2011, 36, 3521.

- Yu, Z.; Liu, T.; Jiang, J.; Liu, K.; Chen, W.; Zhang, X.; Lin, X.; Liu, W. High Q Silica Microbubble Resonators Fabricated by Heating a Pressurized Glass Capillary. Adv. Sens. Syst. Appl. VI 2014, 9274, 92740L.

- Eryürek, M.; Karadag, Y.; Ghafoor, M.; Bavili, N.; Cicek, K.; Kiraz, A. Optical Sensors of Bulk Refractive Index Using Optical Fiber Resonators. Opt. Sens. 2017, 10231, 10231U.

- Memon, S.F.; Lewis, E.; Ali, M.M.; Pembroke, J.T.; Chowdhry, B.S. U-Bend Evanescent Wave Plastic Optical Fibre Sensor for Minute Level Concentration Detection of Ethanol Corresponding to Biofuel Production Rate. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Sensors Applications Symposium (SAS), Glassboro, NJ, USA, 13 March 2017.

- Wu, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, A.P.; Guan, B.-O.; Tam, H.-Y. In-Line Open-Cavity Fabry–Pérot Interferometer Formed by C-Shaped Fiber Fortemperature-Insensitive Refractive Index Sensing. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 21757.

- Zhou, F.; Su, H.; Joe, H.E.; Jun, M.B.G. Temperature Insensitive Fiber Optical Refractive Index Probe with Large Dynamic Range at 1,550 Nm. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2020, 312, 112102.

- Aristilde, S.; Cordeiro, C.M.B.; Osório, J.H. Gasoline Quality Sensor Based on Tilted Fiber Bragg Gratings. Photonics 2019, 6, 51.

- Khalaf, A.L.; Arasu, P.T.; Lim, H.N.; Paiman, S.; Yusof, N.A.; Mahdi, M.A.; Yaacob, M.H. Modified Plastic Optical Fiber with CNT and Graphene Oxide Nanostructured Coatings for Ethanol Liquid Sensing. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 5509–5520.

- Muri, H.I.D.I.; Bano, A.; Hjelme, D.R. First Step towards an Interferometric and Localized Surface Plasmon Fiber Optic Sensor. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Optical Fiber Sensors, Jeju, Korea, 23 April 2017; Volume 10323, p. 1032323.

- Verma, R.; Gupta, B.D. Fiber Optic Surface Plasmon Resonance Based Ethanol Sensor. In Proceedings of the Photonic Instrumentation Engineering, San Francisco, CA, USA, 2–5 February 2014; Soskind, Y.G., Olson, C., Eds.; International Society for Optics and Photonics: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2014; Volume 8992, p. 89920A.

- Nguyen, T.T.; Bae, S.O.; Kim, D.M.; Yoon, W.J.; Park, J.-W.; An, S.S.A.; Ju, H. A Regenerative Label-Free Fiber Optic Sensor Using Surface Plasmon Resonance for Clinical Diagnosis of Fibrinogen. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 155–163.

- Xu, Y.; Xiong, M.; Yan, H. A Portable Optical Fiber Biosensor for the Detection of Zearalenone Based on the Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 336, 129752.

- Elsherif, M.; Moreddu, R.; Hassan, M.U.; Yetisen, A.K.; Butt, H. Real-Time Optical Fiber Sensors Based on Light Diffusing Microlens Arrays. Lab A Chip 2019, 19, 2060–2070.

- Luna Technologies Inc. HD-SC Temperature Sensors; Luna Technologies Inc.: Roanoke, VA, USA, 2021.

- OZ Optics Ltd. Fiber Optic Distributed Strain and Temperature Sensors (DSTS) BOTDA Module; OZ Optics Ltd.: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021.

- Lu, X.; Thomas, P.J.; Hellevang, J.O. A Review of Methods for Fibre-Optic Distributed Chemical Sensing. Sensors 2019, 19, 2876.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!