Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Cell & Tissue Engineering

The use of stem cell mobilization, or homing for regeneration based on endogenous healing mechanisms, prompted a new concept in regenerative medicine: endogenous regenerative medicine.

- endogenous regenerative medicine

- bone regeneration

- dental regeneration

- decellularized extracellular matrix

1. Introduction

Regenerative medicine, and, in particular, tissue engineering, are considered to be promising strategies for the repair of lost/damaged tissues, and aims to improve a patient’s quality of life. Approaches to tissue reconstruction are based on the use of stem cells (SCs), growth factors, signaling molecules, scaffolds and gene therapy. Stem cells, primarily mesenchymal SCs (MSCs) or progenitor cells, obtained from various tissues are attractive therapeutic agents. Their advantages are not only their rapid buildup in required amounts but also differentiation into various cell types to enable the modeling of various technologies for the reconstruction of lost or damaged tissues and organs [1][2]. Compared to regenerative potential, the SC capability of immunomodulation plays a no less important role in achieving a successful result [3]. To date, the use of SCs is considered to be the main strategy in regenerative medicine, including restorative dentistry. Based on therapeutic agents with SC expansion ex vivo, the reconstruction of the lost structures of various tissues was demonstrated in numerous preclinical and clinical studies [4]. However, tissue regeneration by SC transplantation is hindered by many factors, including immune repulsion, pathogen transfer, oncogenesis, the accumulation of genomic alterations and age-related genetic instability, problems with ex vivo manipulations with cells, time-consuming procedures, high costs and difficulties in obtaining regulatory approval [5].

An approach known as cell-free therapy has rapidly developed in regenerative medicine in the past decade, due to the growing volume of knowledge of the SC mechanisms of action. Together with an understanding of the paracrine effects of exogenously administered SCs, the molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways involved in the intrinsic potential of tissue regeneration started to be understood. This prompted the development of novel strategies to control and intensify these processes during regeneration. The use of SC mobilization/homing technology for regeneration based on endogenous healing mechanisms has become a new concept in regenerative medicine and is called endogenous regenerative technology (ERT) [6], endogenous regenerative medicine (ERM) [7][8] or autotherapies [9]. ERM/ERT is especially promising in restorative dentistry due to the large number of patients and one of its most remarkable advantages; the regeneration of merely a small amount of tissue can be very efficient for a patient [10]. Approaches using chemoattractant gradients to monitor tissue regeneration without ex vivo cultured cells are preferable to treatment techniques based on transplanted autologous or allogeneic SCs with limited potential for clinical use.

The development of regenerative approaches in ERM/ERT requires, aside from the knowledge of biological SC homing–regulating signals, requires a comprehensive idea of the characteristics of the resident SCs’ microenvironment/niche, as well as of the extracellular factors involved in SC self-maintenance, to manipulate these cells. The key function of SC niches is to maintain a constant number of slowly dividing cells to balance the proportion of quiescent and activated cells. In a niche, as it is known, SCs are under the spatio-temporal control of an enormous number of factors, including chemokines, cytokines, growth factors, ligands, insoluble transmembrane receptors, proteases, adhesion molecules (selectins and integrins) and extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules [7]. Additionally, external tensile, compressive and shear forces have a massive effect on the phenotype of cells, the properties of the ECM, and the general functions of the niche. In turn, cells in tissues affect their microenvironment by internal mechanical forces—adhesion interactions of their cytoskeleton with the ECM and adjacent cells via the niche [11]. Thus, the interaction and optimization of every niche component involved in ERM is especially important for understanding how the required cell response should be made safe and efficient for therapy [12].

An ever-increasing amount of currently emerging data indicates that the use of cell-free therapeutics leading to endogenous SC recruitment/homing has advantages for overcoming restrictions and risks associated with the use of cell-free therapy, including tumorigenesis, unwanted immune responses and transfer of pathogens. Additionally, it has significant advantages in production, storage and standardization [13][14][15]. Thus, the use of cell-free products in regenerative medicine can improve migration, proliferation, differentiation and metabolism of various resident SCs, which provide for the regulation of their spatially correct arrangement and will stimulate the endogenous regeneration of damaged tissues [16].

2. Extracellular Matrix

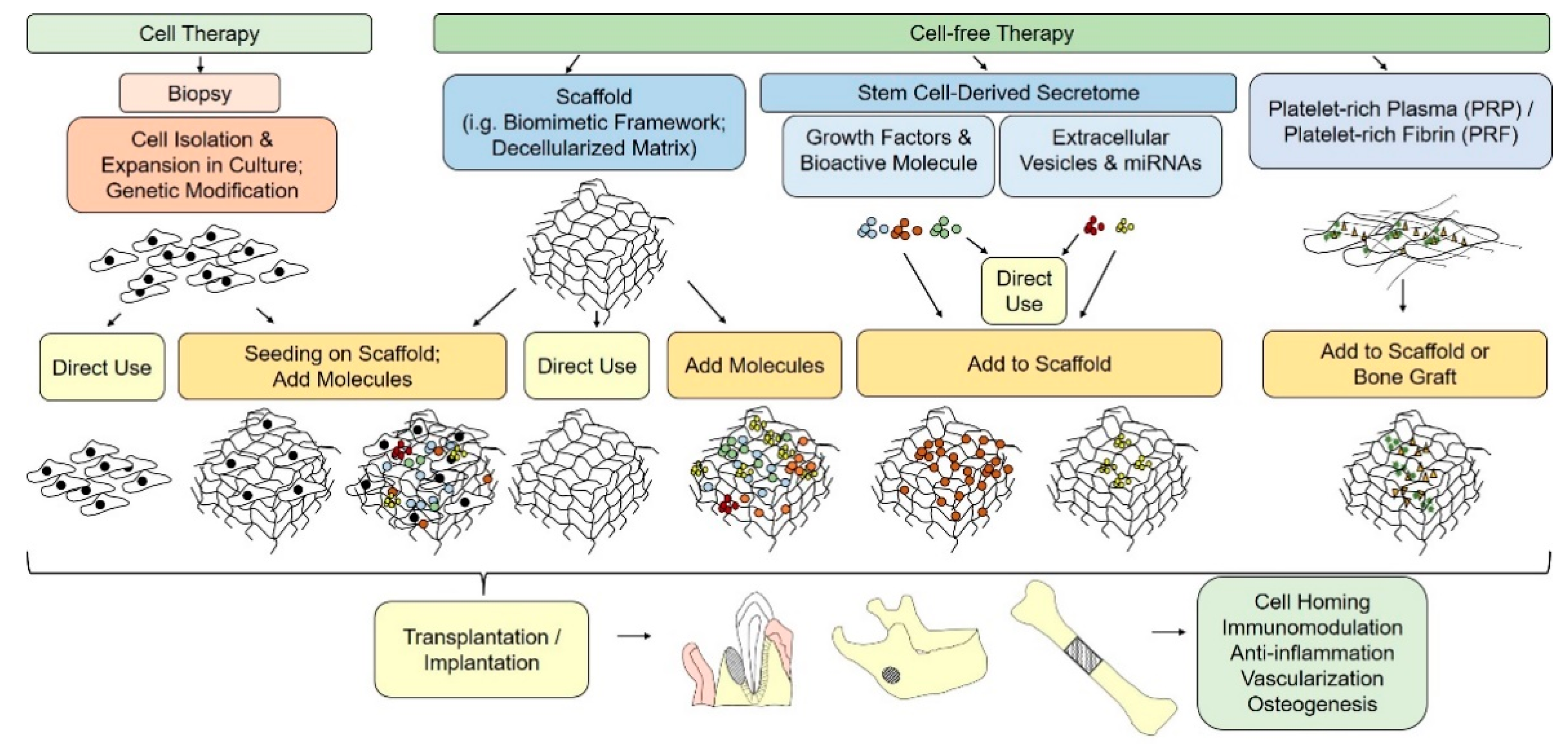

As mentioned above, the leading strategy in ERM is the use of various factors (Figure 1) that stimulate recovery mechanisms by recruiting endogenous SCs into injured areas [17].

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of cell-based and cell-free paradigms for bone tissue engineering.

It is known that, as well as growth factors and various signaling molecules, the traffic of SCs, their oriented migration, survival, self-renewal and differentiation can be regulated and enhanced by the ECM [18].

ECMs are highly specialized and dynamic three-dimensional frameworks that aid the adhesion and functioning of various cells that form the basis of tissues. ECMs consist of numerous fibrillar components such as collagens, fibronectin and elastin, and nonfibrillar molecules such as proteoglycans, hyaluronan and glycoproteins, including matrix cell proteins. They interact with one another via numerous receptors, including integrins, discoidin domain receptors (DDR), proteoglycan surface receptors and hyaluronan receptors such as CD44, RHAMM, LYVE-1 and layilin, creating a multicomponent structural network [19]. For instance, collagen, vitronectin and laminin are common partners for binding integrins. Some integrins can also bind to intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1), which are part of the SC microenvironment [20]. In addition to classical receptors, ECM molecules also interact with and regulate signal transfer via other non-traditional receptors, including growth factor receptors and Toll-like receptors (TLRs) [19]. It is known that the differential expressions of certain receptors determine the type of niche into which cells migrate. Thus, for instance, integrins β1, α5 and αV are usually expressed into adult SCs [20]. ECMs regulate the proliferation, survival, migration and differentiation of cells via matrix–cell interactions. Thus, ECM molecules interact with surface receptors of various cell types, including fibroblasts, immune cells, endothelial cells, epithelial cells and pericytes, by regulating the phenotypes and functions of these cells for tissue homeostasis maintenance.

The ECM molecular composition and structure differ in different tissues and change noticeably at the reconstitution of normal tissue, as well as in the progression of various diseases.

ECMs in tissues such as cartilage and bone differ in their composition and structure from ECM in connective tissue, as they bear significant mechanical loads. The bone contains a specialized ECM, which essentially consists of collagen I, III and V fibrils. Collagen I is a predominant protein that serves as a site for the nucleation of hydroxyapatite and the deposition of crystals on its fibrils. The main ECM components are synthesized by osteoblasts, although terminally differentiated osteoblasts called osteocytes also produce matrix components, such as small integrin-binding ligand N-linked glycoproteins (SIBLING): dentin matrix acidic phosphoprotein 1 (DMP1) and matrix extracellular phospho-glycoprotein (MEPE), involved in phosphate metabolism and bone mineralization [21]. Osteocalcin, osteopontin/bone sialoprotein, as well as small lecithin-rich proteoglycans, such as keratocan and asporin, are also involved in bone mineralization. Decorin, biglycan, asporin, osteonectin/secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC), and thrombospondin are engaged in collagen fibrillogenesis and/or bioavailability/transmission of signals from transforming growth factor (TGF)-β. The mineralized ECM imparts the tissue with rigidity and mechanical strength, and all its components contribute to correct tissue functioning [22]. The ECM acts not only as a physical framework for cells and as a store of signaling molecules, but also as the main regulator of the behavior of SCs in a niche [23][24]. For this reason, various secretory SC products as well as ECM products and ECM-based bioscaffolds are considered, at present, as a new class of biopharmaceuticals in regenerative medicine [25]. As compared with cell-based therapy, the use of biomaterials is simpler and sufficiently reliable for maintaining high levels of endogenous tissue regeneration. Therefore, a well-designed biomaterial-based niche has the potential for activating and recruiting a sufficient amount of SCs from adjacent tissues for safe, functional regeneration [8][26].

In view of the organization of various organs as three-dimensional structures, it is essential to choose for their regeneration an underlying scaffold mimicking the ECM in native tissue. The choice of scaffold materials and design impacts the therapeutic potential and the number and invasiveness of associated clinical procedures [12]. As scaffolds may change their physical and chemical properties and transfer mechanical forces in vivo in response to various internal and external stimuli, they may contribute both to regeneration and to the development of a reaction to a foreign body and fibrosis [11]. This necessitates the complete understanding of cell–scaffold interactions. To date, these interactions are known to be mediated by various adhesion molecules, including integrins and cadherins, which are of crucial importance for cell migration and localization [27]. It is noteworthy that the successful penetration of cells and their presence in the scaffold is regulated by biomaterials’ surface features and cell–matrix interactions of cells with biomaterial [28][29]. Thus, the scaffold constructions designed by tissue engineering can ensure a suitable microenvironment for resident SCs’ homing and the controlled release of biological signals, including matrix-associated growth factors (fibroblast growth factor (FGF), TGF-β, bone morpho-genetic protein (BMP)) [30][31], which aid with model physiological processes, including tissue morphogenesis and regeneration [11].

Overall, scaffolds should meet four main criteria with respect to (1) their shape (correspondence to the geometry of complex three-dimensional defects); (2) function (temporary maintenance of the functional and biomechanical conditions in the course of healing); (3) formation (contribution to regeneration); and (4) fixation (light interaction and integration with adjacent tissues) [32].

Biomimetic frameworks actively developed at present in tissue engineering are formed based on purified ECM components and synthetic or natural polymers [33]. Biomimetic designs attract the ever-increasing attention of many researchers in biomaterials, regenerative biology and regenerative medicine communities. Unfortunately, as of now, bioengineers have failed to construct the basic elements of native tissue [5][34]. However, scaffolds consisting of the main ECM components and/or structures can mimic an in vivo microenvironment occurring in the course of tissue regeneration and, therefore, can contribute to endogenous tissue reconstitution. For instance, a hierarchically structured nanohybrid framework containing a bone-like nano-hydroxyapatite (n-HA) contributes to a homogeneous distribution of n-HA after in vivo transplantation and to interfacial interactions by recruiting endogenous cells for successful bone regeneration in situ [35]. The possibility of constructing a biological activity and changing the parameters of biomaterials’ properties significantly increases the number of potential applications and improves biomaterials’ characteristics in vivo. Recent advances in the biotechnologies of the development of multiphase scaffolds, such as electrospinning and 3D bioprinting, enable the high-accuracy formation of a complex architecture comparable with native bone architecture both in the shape and structure [5]. For instance, Kankala et al. demonstrated a 3D porous scaffold using the innovative combinatorial 3D printing and freeze-drying technologies on gelatin (Gel), n-HA and poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) for bone regeneration [36].

Along with biomimetic frameworks, a strategy, which aims to use decellularized matrices that possess the advantage of a great similarity with the tissue to be replaced, is also being actively developed in tissue engineering. It is crucial to choose proper decellularization methods for obtaining decellularized matrix biomaterials [37], which will greatly affect the ultrastructure, composition and biological actions. It is commonly acknowledged that it is essential to remove cellular elements such as the cell membrane, nucleic acids and mitochondria as much as possible, but keep the functional compositions. Currently, there are many conventional methods to prepare decellularized matrix-based scaffolds. This can be accomplished using physicochemical and chemical methods, including freeze–thaw methods, ultrasonication and freeze drying, treatment with chemical detergents such as Triton X-100 and SDS, or enzymatic treatment with DNase and RNase. Triton X-100 is better for preserving the ECM architecture compared to freeze–thaw cycles [38]. The key part of the decellularization assessment is the analysis of changes produced in the dECM. Providing the presence of most ECM components after the decellularization is of key significance for maintaining its functionality. As ECM-based scaffolds produced by mammalian tissue decellularization exhibit no immune responses, and by their nature contain tissue-specific and matrix-associated factors involved in cell growth and differentiation, they are actively used in bone and dentistry regeneration [39]. In vitro, decellularized bone ECM enhances the osteogenic differentiation of rat MSCs [40], human embryonic SCs [41] and human adipose-derived SCs [42]. In vivo, dECM displayed efficient engraftment and vascularization and was able to undergo remodeling onto an immature osteoid tissue [43]. The dECMs can efficiently integrate into the defect zone and promote bone repair [44]; decellularized periodontal ligaments can reconstruct periodontal tissues by recruiting host cells and evoking their correct orientation in the ligament, which can serve as a novel approach to periodontal treatment [45]. The dECM implanted in the mouse calvarial defect model improved not only new bone formation without any further inflammatory reaction, but also the density of these formations [46].

3. Growth Factors and Signaling Molecules

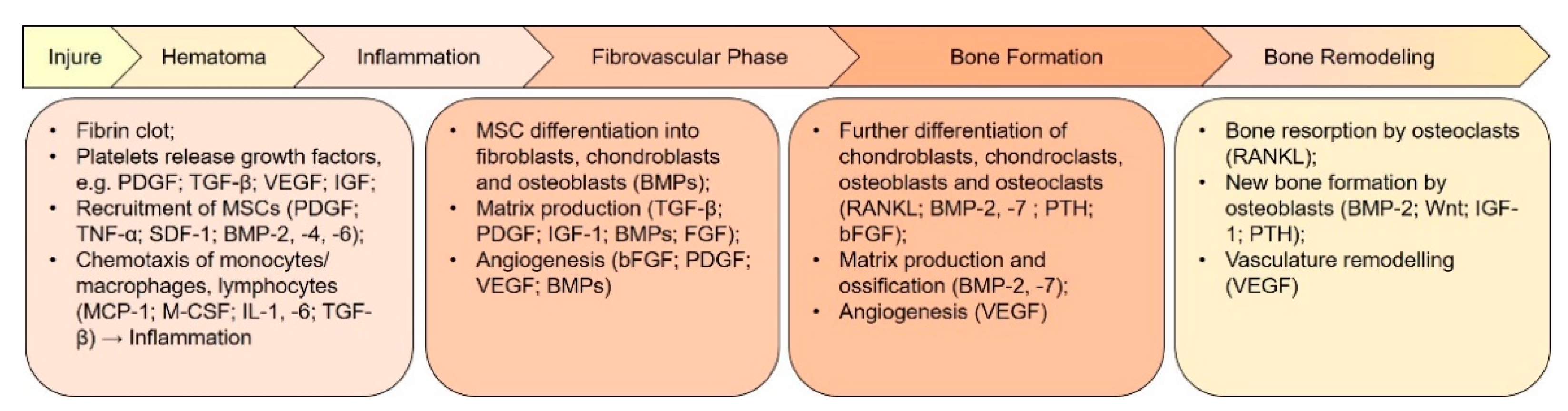

The approach using only scaffolds is often insufficient for reconstructing a biologically suitable extracellular SC microenvironment/niche. In this case, combinations of ECM molecules and growth factors are used [47]. Growth factors and signaling molecules can stimulate chemotaxis, proliferation, differentiation, ECM synthesis and angiogenesis. The biological functions of these molecular mediators widely vary, but their choice as candidates for regenerative therapy of bone and dental tissues is based on their important role in the development of these tissues and their healing [30] (Figure 2). Thus, for instance, during the early phase of bone healing, platelet activation and subsequent degranulation provide a burst of cytokines directly at the injury site. These factors cause the migration of innate immune cells to the site of damage. Recruited immune cells secrete paracrine factors (e.g., TGF, BMP, FGF, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), focal adhesion kinases) that form a favorable microenvironment at the site of damage. This microenvironment promotes the migration of both circulating and local resident populations of reparative cells, such as SCs and progenitor cells, by means of complex signal cascades [7]. As a result, the recruited MSCs begin to differentiate into fibroblasts, chondroblasts, and osteoblasts. BMP-2 and BMP-7 play an important role in the induction of MSC differentiation into osteoblasts [5]. Additionally, TGF-β/BMP, by interacting with various pathways—Wnt, MAPK, Notch, Hh, Akt/mTOR and miRNAs—activates BMP-stimulated signal transmission and induces endogenous bone regeneration [48].

Figure 2. Key growth factors and events involved in the different phases of bone regeneration. The regeneration process can be divided into several phases that overlap each other. Each phase is regulated by many cytokines and growth factors secreted by different cell types. Revascularization and angiogenesis are ongoing through the inflammatory phase until the bone formation phase. BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; bFGF, basic FGF; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1; M-CSF, macrophage colony-stimulating factor; OPG, osteoprotegerin; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; PTH, parathyroid hormone; RANKL, receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand; SDF-1, stromal cell-derived factor 1; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Promising results of preclinical and clinical research led to the subsequent introduction of various growth factors to the commercial market for regeneration of soft and hard tissues [49]. However, there are several known problems associated with growth-factor-based therapy, which should be strictly taken into account: short periods of half-decay in vivo, side effects due to the introduction of several or high doses to achieve efficient therapy, unidentified key growth factors for particular tissues and the possible denaturation of protein during manipulation [5]. The use of scaffolds with required biomolecules adsorbed on them can avoid these problems in the induction of the endogenous regeneration of bone and dental tissues. For instance, the bone ECM can be used as a scaffold for recruiting endogenous progenitors using various signaling molecules or angiogenic factors such as VEGF, proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor TNF-α and interleukin-1, as well as BMP for the stimulation of bone regeneration [47]. Several in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that the addition of various signaling molecules and growth factors, such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, stromal cell-derived factor (SDF), basic FGF (bFGF) and VEGF, to different (natural and syn-thetic) scaffolds enhances the regeneration of intracanal pulp-like tissues due to the stimulation of dentin formation, mineralization, neovascularization and innervation [50]. Decellularized dentin can be modified by platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) to provide signals for MSC recruitment from the circulation and the periodontal ligament for the regeneration of cementum and tissue similar to the periodontal ligament with oriented fibers, which ultimately restores the interface between soft and hard tissues [51].

The combination of recombinant human BMP-2 (rhBMP-2) on an absorbable collagen sponge carrier was shown to induce bone formation in a number of preclinical and clinical investigations [52]. The main issue associated with the absorbable collagen sponge is an initial burst release of rhBMP-2 into the local environment, leading to heterotrophic ossification [53]. One reason that BMP carriers are loaded with supraphysiological concentrations is likely related to the need to overcome the regulating factors of BMP inhibitors in order to achieve a therapeutic response. These inhibitors are present within the BMP signaling cascade at intracellular locations, as pseudo-receptors, and in extracellular locations [54]. In order to successfully decrease the therapeutic concentration of BMPs, novel carrier systems that maintain or enhance rhBMP-2 bioactivity must be designed and the negative feedback signaling caused by BMP antagonists must be addressed.

A particularly intriguing approach is the modification of known growth factors with so-called superaffinity domains, which allows these growth factors to achieve effects at a lower effective dose through better binding affinity to their carrier material or ECM proteins [55].

Thus, the main tendencies in acellular bone tissue engineering today are directed to the creation of an ECM-based bioscaffold, usually by including several key growth factors for mimicking the natural bone structure and developing an environment for maintaining osteogenesis, osteoconduction and/or osteoinduction [56]. Although the use of growth factors appears to be an extremely attractive strategy for establishing a microenvironment around an implanted scaffold, problems associated with its efficiency and safety remain. The targeted delivery of growth factors can be a complicated problem, because they rapidly degrade and diffuse into surrounding tissues. The potency of each cytokine in a cocktail differs from its individual action; thus, the synergistic or antagonistic effects of multiple cytokines on a given cell population must be tested under different in vivo situations [57]. Further research into the molecular pathways underlying the process of SC recruitment is required to assess the real potential of the growth factors. Studies that aim to trace in vivo SC migration in response to the local gradients of the growth factors may help find new biological signals and improve the selectivity of the existing signals [17].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms222413454

References

- Han, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Han, Y.; Chang, F.; Ding, J. Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Regenerative Medicine. Cells 2019, 8, 886.

- Shammaa, R.; El-Kadiry, A.E.H.; Abusarah, J.; Rafei, M. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Beyond Regenerative Medicine. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 72.

- Racz, G.Z.; Kadar, K.; Foldes, A.; Kallo, K.; Perczel-Kovach, K.; Keremi, B.; Nagy, A.; Varga, G. Immunomodulatory and Potential Therapeutic Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Periodontitis. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2014, 65, 327–339.

- Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Sun, M.; Xu, H.; Gao, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, M. Characterization and Therapeutic Applications of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Regenerative Medicine. Tissue Cell 2020, 64, 101330.

- Galli, M.; Yao, Y.; Giannobile, W.V.; Wang, H.-L. Current and Future Trends in Periodontal Tissue Engineering and Bone Regeneration. Plast. Aesthet. Res. 2021, 8, 3.

- Chen, F.M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; An, Y.; Chen, F.; Wu, Z.F. A Review on Endogenous Regenerative Technology in Periodontal Regenerative Medicine. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 7892–7927.

- Wu, R.X.; Xu, X.Y.; Wang, J.; He, X.T.; Sun, H.H.; Chen, F.M. Biomaterials for Endogenous Regenerative Medicine: Coaxing Stem Cell Homing and Beyond. Appl. Mater. Today 2018, 11, 144–165.

- Xu, X.Y.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; He, X.T.; Sun, H.H.; Chen, F.M. Concise Review: Periodontal Tissue Regeneration Using Stem Cells: Strategies and Translational Considerations. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2019, 8, 392–403.

- Lumelsky, N.; O’Hayre, M.; Chander, P.; Shum, L.; Somerman, M.J. Autotherapies: Enhancing Endogenous Healing and Regeneration. Trends Mol. Med. 2018, 24, 919–930.

- Anitua, E.; Sánchez, M.; Orive, G. Potential of Endogenous Regenerative Technology for In Situ Regenerative Medicine. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2010, 62, 741–752.

- Lumelsky, N. Creating a Pro-regenerative Tissue Microenvironment: Local Control is the Key. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 712685.

- Wagers, A.J. The Stem Cell Niche in Regenerative Medicine. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 10, 362–369.

- Herberts, C.A.; Kwa, M.S.G.; Hermsen, H.P.H. Risk Factors in the Development of Stem Cell Therapy. J. Transl. Med. 2011, 9, 29.

- Kim, H.O.; Choi, S.M.; Kim, H.S. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Secretome and Microvesicles as a Cell-Free Therapeutics for Neurodegenerative Disorders. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2013, 10, 93–101.

- Sagaradze, G.D.; Nimiritsky, P.P.; Akopyan, Z.A.; Makarevich, P.I.; Efimenko, A.Y. “Cell-Free Therapeutics” from Components Secreted by Mesenchymal Stromal Cells as a Novel Class of Biopharmaceuticals. In Biopharmaceuticals; Yeh, M.-K., Chen, Y.-C., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018.

- Granz, C.L.; Gorji, A. Dental Stem Cells: The Role of Biomaterials and Scaffolds in Developing Novel Therapeutic Strategies. World J. Stem Cells 2020, 12, 897–921.

- Pacelli, S.; Basu, S.; Whitlow, J.; Chakravarti, A.; Acosta, F.; Varshney, A.; Modaresi, S.; Berkland, C.; Paul, A. Strategies to Develop Endogenous Stem Cell-Recruiting Bioactive Materials for Tissue Repair and Regeneration. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2017, 120, 50–70.

- Lane, S.W.; Williams, D.A.; Watt, F.M. Modulating the Stem Cell Niche for Tissue Regeneration. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 795–803.

- Theocharis, A.D.; Skandalis, S.S.; Gialeli, C.; Karamanos, N.K. Extracellular Matrix Structure. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 97, 4–27.

- Morrison, S.J.; Spradling, A.C. Stem Cells and Niches: Mechanisms That Promote Stem Cell Maintenance Throughout Life. Cell 2008, 132, 598–611.

- Mansour, A.; Mezour, M.A.; Badran, Z.; Tamimi, F. Extracellular Matrices for Bone Regeneration: A Literature Review. Tissue Eng. Part A 2017, 23, 1436–1451.

- Alford, A.I.; Kozloff, K.M.; Hankenson, K.D. Extracellular Matrix Networks in Bone Remodeling. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2015, 65, 20–31.

- Lander, A.D.; Kimble, J.; Clevers, H.; Fuchs, E.; Montarras, D.; Buckingham, M.; Calof, A.L.; Trumpp, A.; Oskarsson, T. What Does the Concept of the Stem Cell Niche Really Mean Today? BMC Biol. 2012, 10, 19.

- Linde-Medina, M.; Marcucio, R. Living Tissues Are More Than Cell Clusters: The Extracellular Matrix as a Driving Force in Morphogenesis. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2018, 137, 46–51.

- Paul, A.; Manoharan, V.; Krafft, D.; Assmann, A.; Uquillas, J.A.; Shin, S.R.; Hasan, A.; Hussain, M.A.; Memic, A.; Gaharwar, A.K.; et al. Nanoengineered Biomimetic Hydrogels for Guiding Human Stem Cell Osteogenesis in Three Dimensional Microenvironments. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 3544–3554.

- Li, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, C. The Horizon of Materiobiology: A Perspective on Material-Guided Cell Behaviors and Tissue Engineering. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 4376–4421.

- Song, J.J.; Ott, H.C. Organ Engineering Based on Decellularized Matrix Scaffolds. Trends Mol. Med. 2011, 17, 424–432.

- Katti, D.; Vasita, R.; Shanmugam, K. Improved Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering Applications: Surface Modification of Polymers. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 341–353.

- Ventre, M.; Netti, P.A. Engineering Cell Instructive Materials to Control Cell Fate and Functions Through Material Cues and Surface Patterning. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 14896–14908.

- Chen, F.M.; Zhang, M.; Wu, Z.F. Toward Delivery of Multiple Growth Factors in Tissue Engineering. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 6279–6308.

- Sun, H.H.; Qu, T.J.; Zhang, X.H.; Yu, Q.; Chen, F.M. Designing Biomaterials for In Situ Periodontal Tissue Regeneration. Biotechnol. Prog. 2012, 28, 3–20.

- Hollister, S.J. Scaffold Design and Manufacturing: From Concept to Clinic. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 3330–3342.

- Yu, Y.; Wu, R.X.; Yin, Y.; Chen, F.M. Directing Immunomodulation Using Biomaterials for Endogenous Regeneration. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 569–584.

- Kyburz, K.A.; Anseth, K.S. Synthetic Mimics of the Extracellular Matrix: How Simple is Complex Enough? Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 43, 489–500.

- Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, P.; Fan, T.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Q. In Situ Strategy for Bone Repair by Facilitated Endogenous Tissue Engineering. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2015, 135, 581–587.

- Kankala, R.K.; Xu, X.M.; Liu, C.G.; Chen, A.Z.; Wang, S.B. 3D-Printing of Microfibrous Porous Scaffolds Based on Hybrid Approaches for Bone Tissue Engineering. Polymers 2018, 10, 807.

- Hussey, G.S.; Dziki, J.L.; Badylak, S.F. Extracellular Matrix-Based Materials for Regenerative Medicine. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018, 3, 159–173.

- Chen, G.; Lv, Y. Decellularized Bone Matrix Scaffold for Bone Regeneration. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1577, 239–254.

- Hillebrandt, K.H.; Everwien, H.; Haep, N.; Keshi, E.; Pratschke, J.; Sauer, I.M. Strategies Based on Organ Decellularization and Recellularization. Transpl. Int. 2019, 32, 571–585.

- Hashimoto, Y.; Funamoto, S.; Kimura, T.; Nam, K.; Fujisato, T.; Kishida, A. The Effect of Decellularized Bone/Bone Marrow Produced by High-Hydrostatic Pressurization on the Osteogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 7060–7067.

- Marcos-Campos, I.; Marolt, D.; Petridis, P.; Bhumiratana, S.; Schmidt, D.; Vunjak-Novakovic, G. Bone Scaffold Architecture Modulates the Development of Mineralized Bone Matrix by Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 8329–8342.

- Fröhlich, M.; Grayson, W.L.; Marolt, D.; Gimble, J.M.; Kregar-Velikonja, N.; Vunjak-Novakovic, G. Bone Grafts Engineered from Human Adipose-Derived Stem Cells in Perfusion Bioreactor Culture. Tissue Eng. Part A 2010, 16, 179–189.

- Sadr, N.; Pippenger, B.E.; Scherberich, A.; Wendt, D.; Mantero, S.; Martin, I.; Papadimitropoulos, A. Enhancing the Biological Performance of Synthetic Polymeric Materials by Decoration with Engineered, Decellularized Extracellular Matrix. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 5085–5093.

- Zimmermann, G.; Moghaddam, A. Allograft Bone Matrix Versus Synthetic Bone Graft Substitutes. Injury 2011, 42 (Suppl. S2), S16–S21.

- Nakamura, N.; Ito, A.; Kimura, T.; Kishida, A. Extracellular Matrix Induces Periodontal Ligament Reconstruction In Vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3277.

- Lee, M.S.; Lee, D.H.; Jeon, J.; Tae, G.; Shin, Y.M.; Yang, H.S. Biofabrication and Application of Decellularized Bone Extracellular Matrix for Effective Bone Regeneration. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2020, 83, 323–332.

- Martino, M.M.; Briquez, P.S.; Maruyama, K.; Hubbell, J.A. Extracellular Matrix-Inspired Growth Factor Delivery Systems for Bone Regeneration. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015, 94, 41–52.

- Wang, X.; Wang, G.; Zingales, S.; Zhao, B. Biomaterials Enabled Cell-Free Strategies for Endogenous Bone Regeneration. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2018, 24, 463–481.

- Karakaya, I.; Ulusoy, N. Basics of Dentin-Pulp Tissue Engineering. AIMS Bioeng. 2018, 5, 162–178.

- Eramo, S.; Natali, A.; Pinna, R.; Milia, E. Dental Pulp Regeneration Via Cell Homing. Int. Endod. J. 2018, 51, 405–419.

- Ji, B.; Sheng, L.; Chen, G.; Guo, S.; Xie, L.; Yang, B.; Guo, W.; Tian, W. The Combination Use of Platelet-Rich Fibrin and Treated Dentin Matrix for Tooth Root Regeneration by Cell Homing. Tissue Eng. Part A 2015, 21, 26–34.

- McKay, W.F.; Peckham, S.M.; Badura, J.M. A Comprehensive Clinical Review of Recombinant Human Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 (INFUSE® Bone Graft). Int. Orthop. 2007, 31, 729–734.

- Brown, K.V.; Li, B.; Guda, T.; Perrien, D.S.; Guelcher, S.A.; Wenke, J.C. Improving Bone Formation in a Rat Femur Segmental Defect by Controlling Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 Release. Tissue Eng. Part A 2011, 17, 1735–1746.

- Tsiridis, E.; Upadhyay, N.; Giannoudis, P. Molecular Aspects of Fracture Healing: Which are the Important Molecules? Injury 2007, 38 (Suppl. S1), S11–S25.

- Martino, M.M.; Briquez, P.S.; Güç, E.; Tortelli, F.; Kilarski, W.W.; Metzger, S.; Rice, J.J.; Kuhn, G.A.; Müller, R.; Swartz, M.A.; et al. Growth Factors Engineered for Super-Affinity to the Extracellular Matrix Enhance Tissue Healing. Science 2014, 343, 885–888.

- Kowalczewski, C.J.; Saul, J.M. Biomaterials for the Delivery of Growth Factors and Other Therapeutic Agents in Tissue Engineering Approaches to Bone Regeneration. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 513.

- Fong, E.L.S.; Watson, B.M.; Kasper, F.K.; Mikos, A.G. Building Bridges: Leveraging Interdisciplinary Collaborations in the Development of Biomaterials to Meet Clinical Needs. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 4995–5013.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!