Ischemic stroke is a life-threatening cerebral vascular disease and accounts for high disability and mortality worldwide. Currently, no efficient therapeutic strategies are available for promoting neurological recovery in clinical practice, except rehabilitation. The majority of neuroprotective drugs showed positive impact in pre-clinical studies but failed in clinical trials. Therefore, there is an urgent demand for new promising therapeutic approaches for ischemic stroke treatment. Emerging evidence suggests that exosomes mediate communication between cells in both physiological and pathological conditions. Exosomes have received extensive attention for therapy following a stroke, because of their unique characteristics, such as the ability to cross the blood brain–barrier, low immunogenicity, and low toxicity. An increasing number of studies have demonstrated positively neurorestorative effects of exosome-based therapy, which are largely mediated by the microRNA cargo. Herein, we review the current knowledge of exosomes, the relationships between exosomes and stroke, and the therapeutic effects of exosome-based treatments in neurovascular remodeling processes after stroke. Exosomes provide a viable and prospective treatment strategy for ischemic stroke patients.

- exosome

- ischemic stroke

- microRNA

- neurorestoration

1. Introduction

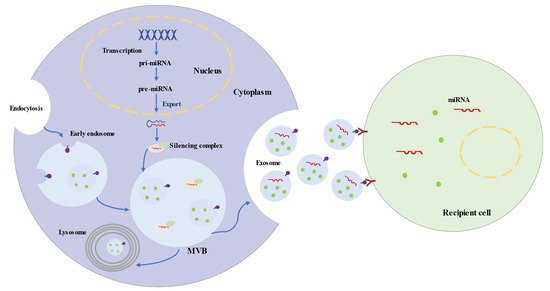

2. Characteristics of Exosomes

3. Roles of Exosomes in Ischemic Stroke

3.1. Exosomes and Ischemic Stroke Diagnosis

| microRNAs | Expression in IS | Sources | Models | Outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-9 | upregulation | serum | Human | NIHSS score, infarct volume, serum IL-6 |

[59] |

| miR-124 | upregulation | serum | Human | NIHSS score, infarct volume, serum IL-6 |

[59] |

| miR-223 | upregulation | serum | Human | NIHSS score, infarct volume, 3-month mRS, stroke occurrence |

[60] |

| miR-134 | upregulation | serum | Human | NIHSS score, infarct volume, serum IL-6, hs-CRP |

[62] |

| miR-422a | upregulation in acute phase downregulation in subacute phase |

plasma | Human | different stages of IS | [63] |

| miR-125-2-3p | downregulation | plasma | Human | different stages of IS | [63] |

| miR-21-5p | upregulation in subacute phase upregulation in recovery phase |

plasma | Human | different stages of IS | [64] |

| miR-30a-5p | upregulation in hyperacute phase downregulation in acute phase |

plasma | Human | different stages of IS | [64] |

| miR-17-5p | upregulation | serum | Human | subtypes of stroke | [65] |

| miR-20b-5p | upregulation | serum | Human | subtypes of stroke | [65] |

| miR-27b-3p | upregulation | serum | Human | subtypes of stroke | [65] |

| miR-93-5p | upregulation | serum | Human | subtypes of stroke | [65] |

| miR-15a | downregulation | serum | Human | subgroups of stroke | [66] |

| miR-100 | downregulation | serum | Human | subgroups of stroke | [66] |

| miR-339 | downregulation | serum | Human | subgroups of stroke | [66] |

| miR-424 | downregulation | serum | Human | subgroups of stroke | [66] |

| miR-122-5p | downregulation | plasma | Rat | different stages of IS | [67] |

| miR-300-3p | upregulation | plasma | Rat | different stages of IS | [67] |

| miR-126 | downregulation | serum | Rat | different stages of IS | [61] |

3.2. Exosomes and Ischemic Stroke Treatment

| microRNAs | Models | Sources | Proposed Effects | Involved Pathway | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-133b | MCAO-rat | MSC | Neural remodeling | CTGF | [86,87,88] |

| miR-17-92 cluster | MCAO-rat | MSC | Neural remodeling | PTEN/Akt/mTOR pathway | [90] |

| miR-138-5p | MCAO-mouse OGD-astrocyte |

MSC | Anti-inflammation Anti-apoptosis | Lipocalin 2 | [91] |

| miR-30d-5p | MCAO-rat OGD-microglia |

MSC | Anti-inflammation Anti-apoptosis |

Beclin-1/Atg5 | [92] |

| miR-223-3p | MCAO-rat OGD-microglia |

MSC | Anti-inflammation | CysLT2R-ERK1/2 | [93,99] |

| miR-1906 | MCAO-mouse OGD-neuron |

MSC | Anti-inflammation | TLR4 | [94] |

| miR-132-3p | MCAO-mouse endothelial cell |

MSC | BBB protection Reduce vascular ROS |

PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway | [95] |

| miR-21-3p | MCAO-rat | MSC | BBB protection Anti-inflammation Anti-apoptosis |

MAT2B | [96] |

| miR-134 | OGD-oligodendrocyte | MSC | Anti-apoptosis | Caspase-8 | [97] |

| miR-184 | MCAO-rat | MSC | Neurogenesis Angiogenesis |

---- | [98] |

| miR-210 | MCAO-rat | MSC | Neurogenesis Angiogenesis |

ephrin-A3 | [98] |

| miR-126 | MCAO-mouse | EPC | Neurogenesis Angiogenesis Anti-apoptosis |

Caspase-3VEGFR2 | [100,101] |

| miR-181b-5p | OGD-endothelial cell | MSC | Angiogenesis | TTRPM7 | [102] |

| miR-132 | zebrafish larvaeendothelial cell | Neuron | Angiogenesis | Cdh5/eEF2K | [54] |

| miR-124 | Photothrombosis mouse | MSC | Neurogenesis | GLI3 STAT3 |

[103] |

| MCAO-mouse OGD-neuron |

M2 microglia | Anti-apoptosis | USP14 | [104] | |

| miR-137 | MCAO-mouse OGD-neuron |

Microglia | Anti-apoptosis | Notch1 | [105] |

| miR-22-3p | MCAO-rat OGD-neuron |

MSC | Anti-apoptosis | KDM6B/BMP2/BMF axis | [106] |

| miR-34c | MCAO-rat OGD-neuroblastoma cells |

Astrocyte | Anti-inflammation Anti-apoptosis |

TLR7 and NFκB/MAPK pathways |

[107] |

| miR-146a-5p | MCAO-mouse OGD-microglia |

MSC | Anti-inflammation | IRAK1/TRAF6 pathway | [108] |

4. Potential Therapeutic Effects of Exosomes in Ischemic Stroke

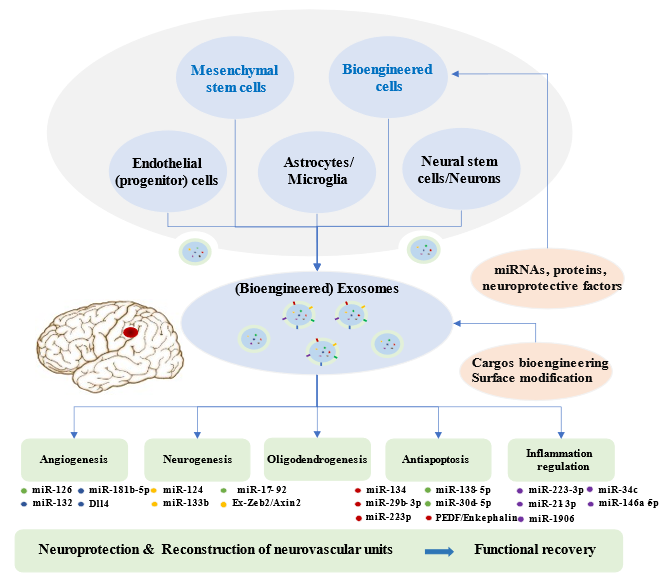

Brain restoration after ischemic stroke involves a series of highly interactive processes, including angiogenesis, neurogenesis, oligodendrogenesis, anti-apoptosis, and immune responses, which together accelerate the reconstruction of neurovascular units and neurological recovery [109-111]. Recent experiments illustrated that the synthesis and secretion of exosomes and their contents are significantly altered after ischemic events, which may suggest potential targets of the disease [52]. An increasing number of preclinical studies indicated that exosomes from stem cells mediate beneficial effects in ischemic repair by amplifying endogenous brain repair processes (Figure 2) [73, 112].

Exosomes derived from multiple cells, including mesenchymal stem cells, endothelial progenitor cells, endothelial cells, astrocytes, microglia, neural stem cells, neuron, and bioengineered cells, can improve the reconstruction of neurovascular units and functional recovery through angiogenesis, neurogenesis, oligodendrogenesis, anti-apoptotic mechanisms, and inflammation regulation following stroke. Exosomes exert beneficial effects in the repair processes mainly via miRNAs. Bioengineered exosomes with cargo or surface modifications will enhance the therapeutic effects.

Figure 2. Brain Restoration Processes Regulated by Exosomes after Ischemic Stroke.

4.1. Angiogenesis

In response to insufficient blood supply after ischemic stroke, the administration of agents to pharmacologically facilitate angiogenesis and restore the blood flow is a common approach. The administration of exosomes with abundant content involving miRNAs, proteins, and lipids may be a novel choice. BMMSCs-derived exosomes were observed to improve the proliferation of cerebral endothelial cells in ischemic animal models [77, 98]. miR-126 targeted vascular cell adhesion protein 1 (VCAM-1) and regulated endothelial cell function and angiogenesis [113]. Exosomal miR-126 was downregulated after oxygen–glucose deprivation in brain endothelial cells and in mice after MCAO [61]. Bihl et al. revealed that exosomes obtained from endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) promoted angiogenesis and neurogenesis in diabetic ischemic stroke mice. Enrichment of miR-126 showed an enhancement of the therapeutic efficacy of EPC-derived exosomes [100]. Moreover, exosomes secreted by adipose-derived stem cells were rich in miRNA-181b-5p. They showed beneficial effects in regulating angiogenesis via suppressing transient receptor potential melastatin 7 (TRPM7) after stroke [102]. Neuron-derived exosomes could deliver miR-132 to endothelial cells to govern cerebral vascular integrity [54]. In addition, the Dll4–Notch signaling pathway in endothelial cells and pericytes is crucial for angiogenesis and BBB integrity. Exosomes derived from human microvascular endothelial cells containing Dll4 proteins regulated angiogenesis. Further research in stroke models is required [114].

4.2. Neurogenesis

Neurogenesis together with angiogenesis are vital processes in the recovery from ischemic stroke. Various studies have shown that exosome-based therapy contributes to alterations of neural stem cells and promotes neurogenesis. Exosomes extracted from BMMSCs could promote the proliferation of cerebral neurons after ischemic injury [77]. miR-124 is abundantly expressed in brain tissue and performs a crucial role in neurogenesis; its overexpression can result in neuronal differentiation [115]. The expression of miR-124 was upregulated in ischemic areas following MCAO [116]. Yang et al. revealed that miR-124-loaded exosomes alleviate ischemic injury by facilitating neural progenitor cells differentiation into neuronal lineages [103, 104]. Furthermore, MSCs-harvested exosomes with elevated miR-17-92 cluster targeted to the PTEN/Akt pathway in recipient cells led to reduced PTEN and increased phosphorylation of Akt and mTOR, eventually increasing newly generated neurons, neuroplasticity, and oligodendrogenesis in MCAO rats [90]. Exosomes originating from MSCs mediated miR-133b delivery to neurons and astrocytes, which led to the downregulation of CTGF and the secondary release of exosomes from astrocytes, subsequently contributing to neurite outgrowth [86-88]. Additionally, Ex-Zeb2/Axin2-enriched exosomes from BMMSCs decreased the expression of SOX10, endothelin-3/EDNRB, and Wnt/β-catenin in MCAO rats, finally improving neuroplasticity and functional recovery [41]. In summary, the utilization of exosomes with active components could be part of a scheme to enhance neurogenesis and activate neuroplasticity, improving neurological recovery after ischemic stroke.

4.3. Anti-apoptosis

Apoptosis is widely involved in the pathogenesis of ischemic stroke and has become an essential target for intervention [117]. Increasing studies have indicated that cell-derived exosomes could inhibit apoptosis and contribute to alleviating cerebral injury in ischemic models [83, 92]. Exosomes from different cells demonstrated neuroprotective potential in ischemia-induced neuronal death[105, 118-120]. MiR-134 was involved in modulating neuronal cell death following ischemia–reperfusion injury [121]. BMMSCs-generated exosomes suppressed oligodendrocyte apoptosis through downregulating the caspase-8 apoptosis pathway via miR-134, which could be a novel therapeutic target for ischemic injury treatment [97]. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (LCN2) is highly expressed after ischemic stroke and is involved in neuron death and brain injury. miR-138-5p is the negatively regulatory factor for LCN2. BMMSCs-released exosomes with overexpressed miR-138-5p downregulated LCN2, caspase-3, and Bax levels, inhibited apoptosis of astrocytes injured by OGD, and reduced neuron injury following ischemia [91]. miR-30d-5p was downregulated in ischemic models. miR-30d-5p-enhanced exosomes showed protective effect against neuronal apoptosis [92]. miR-22-3p in exosomes had beneficial effects in reducing apoptosis and cerebral ischemic injury through the KDM6B/BMP2/BMF axis [106]. Exosomes extracted from endothelial cells protected nerve cells from ischemia–reperfusion injury, partly via inhibiting the apoptosis pathway related to caspase-3, Bax, and Bcl-2 [122]. Furthermore, ADMSCs-derived exosomes with pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) overexpression prevented cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury in stroke rats through regulating apoptotic factors and activating autophagy [123]. Enkephalin delivery via exosomes released from BMMSCs decreased the expression of p53, caspase-3, and NO, increased neuronal density, and accelerated neurological recovery after rat stroke [124]. In a word, exosomes play a crucial role in anti-apoptosis following ischemic stroke, which is worthy of further exploration.

4.4. Inflammation

Inflammation is one of the crucial pathogenic mechanisms of cerebral ischemia, leading to secondary injury to the brain. MSCs-derived exosomes could ameliorate acute ischemic or ischemia–reperfusion injury by regulating anti-inflammatory molecules (IL-4 and IL-10) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β), inhibiting microglial inflammation [92]. miR-30d-5p-enhanced exosomes showed a significant effect in modulating microglial phenotypes and in reducing the levels of inflammatory cytokines [92]. Zhao et al. illustrated that exosomes released from BMMSCs exerted anti-inflammatory effects through modulating CysLT2R-ERK1/2-mediated microglia M1 polarization via miR-223-3p [93, 99]. Liu et al. reported that BMMSCs-derived exosomes attenuated ischemia–reperfusion injury via the inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated inflammation and pyroptosis [125]. ADMSCs-derived exosomes suppressed inflammation and apoptosis via miR-21-3p reduction and MAT2B upregulation in hypoxia/reoxygenation-treated cells [96]. Moreover, exosomes enriched with miR-138-5p or miR-1906 suppressed pro-inflammatory signaling cascades and inhibited inflammatory responses, thereby enhancing rehabilitation following stroke [91, 94]. In addition, miR-126 level was reduced in both ischemic patients and animal models of ischemia. miR-126-rich exosomes suppressed neuroinflammation, promoted neurogenesis, and improved functional recovery after stroke[101]. microRNA-34c in astrocyte-released exosomes exerted a neuroprotective effect by downregulating TLR7 and NF-κB/MAPK pathways[107]. miR-146a-5p derived from human umbilical MSC exosomes inhibited microglial-mediated neuroinflammation via the IRAK1/TRAF6 pathway[108]. Accordingly, anti-inflammation is a pivotal mechanism against ischemic injury; targeting specific exosomes related to it may be beneficial.

5. Advantages and Modifications of Exosomes for the Therapy of Ischemic Stroke

Exosomes play crucial roles in paracrine pathways of cell therapy and have several advantages over whole cells. Exosomes have minimal oncogenicity, immunogenicity, and toxicity. Abundant exosomes can be produced from a small number of cells and can be stored stably. Moreover, exosomes can cross the BBB and function better than whole cells in the brain [126]. As a consequence, treatments based on exosomes have become a new approach for the treatment of neurological diseases.

Based on the characteristics of exosomes, appropriate modifications of exosomes lead to better clinical efficacy and provide more treatment options. Exosomes mediate therapeutic effects by transferring their cargos, especially microRNAs, thus modulating various pathways [27]. Consequently, engineering exosomes by enriching them with modifying microRNAs can more efficiently activate remodeling and protective pathways within the central nervous system. Compared with normal MSCs-derived exosomes, miR-133b-overexpressing, miR-17-92 cluster-enriched, or miR138-5p-filled MSCs-exosomes improved brain remodeling and functional recovery after stroke [88,90,91]. The directional manipulation of two or more main miRNAs in exosomes from stem cells can potentially enhance the curative effects of exosome. Overexpression of PEDF in exosomes had a good impact on the suppression of apoptosis and ischemic injury [123]. Exosomes highly expressing hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) may also have therapeutic potential. Furthermore, 98% of all small-molecule drugs cannot pass through the BBB and be efficiently delivered into the brain [127]. Exosomes will be appropriate for delivering pharmacological agents (such as curcumin and enkephalin) and result in considerable therapeutic impacts [124, 128].

Additionally, modifications of exosomes surface could further help to enhance specific cell targeting. Rabies virus glycoprotein (RVG) was engineered to bind exosomes when combined with protein lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 2b (Lamp2b), which allowed neuron-specific targeting [129]. Yang et al. found that RVG-exosomes could efficiently transfer miR-124 to the infarct location and enhance neuronal protection after ischemic damage [103]. Engineered exosomes conjugated with c (RGDyK) [cyclo (Arg–Gly–Asp–D-Tyr–Lys)] also could target the lesion site of ischemic brain. cRGD–Exo loaded with curcumin led to the inhibition of inflammation and cellular apoptosis [128]. The fusion protein RGD–C1C2 (Arg–Gly–Asp acid 4C peptide fused to lactadherin) bound to exosomes targeted a lesion in ischemic brain and suppressed inflammation [130]. Nevertheless, the modification of exosomes for stroke treatment needs in depth research in the future.

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Ischemic stroke is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Early diagnosis and treatment are the main challenges in clinical practice. Exosomes are released from almost all living cells and play significant roles in intercellular communication. Exosomes are deemed powerful biomarkers for the diagnosis of stroke, and exosomes therapies are efficient approaches to improve brain repair through delivering pharmacological agents or genes after stroke. However, exosomes research remains in its initial stage, particularly for ischemic stroke; no adequate information is available to translate exosomes treatment into clinical practice. A better understanding of exosomes will be beneficial to stroke diagnosis and therapy. Exosomes therapy still has many limitations and presents many challenges. Firstly, the content of exosomes including proteins, miRNAs, and lipids varies, depending on the donor cells, the conditions of cell culture, and exosome extraction. The optimization of operational procedures is necessary, and the characterization of exosome cargos mediating therapeutic effects is warranted. Secondly, new costless techniques for obtaining high-purity exosomes in large amounts need to be developed. Lastly, the extension of exosomes’ half-life and the improvement of their targeting ability require attention for their application in medicine. In conclusion, clinical-grade exosomes appear to be novel promising therapeutic approaches and require further studies.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biom12010115