The immune system has a crucial role in skin wound healing and the application of specific cell-laden immunomodulating biomaterials emerged as a possible treatment option to drive skin tissue regeneration. Cell-laden tissue-engineered skin substitutes have the ability to activate immune pathways, even in the absence of other immune-stimulating signals. In particular, mesenchymal stem cells with their immunomodulatory properties can create a specific immune microenvironment to reduce inflammation, scarring, and support skin regeneration.

- biomaterials

- skin substitutes

- intrinsic immune cell signals

- immunomodulation

- wound healing

- chronic wounds

- skin tissue engineering

- regenerative medicine

1. Introduction

2. Skin

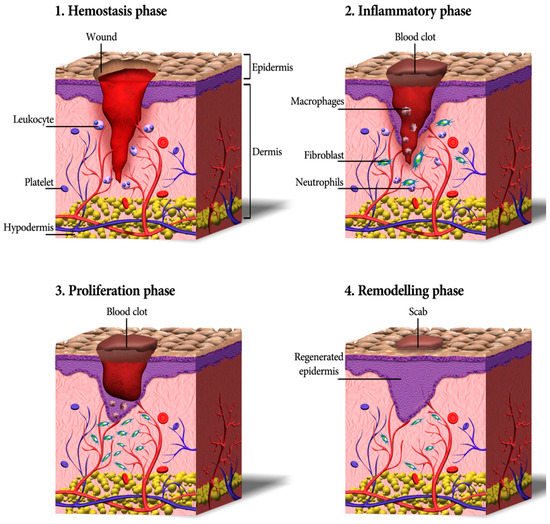

3. Skin Wound Healing Process

4. Application of Stem Cells in Skin Substitutes

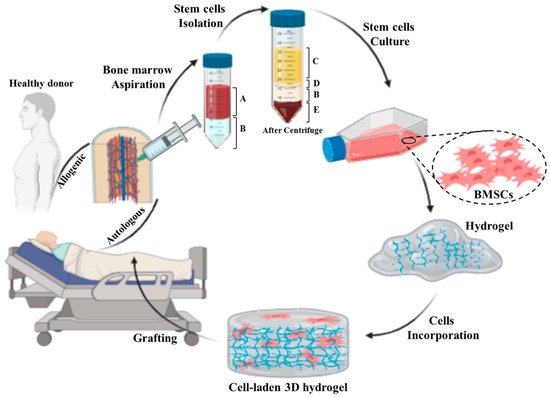

According to the findings obtained by McCulloch and Till, based on [56][57], stem cells can be defined two prominent features: (1) they are undifferentiated and renew themselves for the entire life span and (2) they have an extraordinary potential to develop from a common precursor into multiple cell types with particular functions [15]. Stem cell-based therapies have the potential to enhance cutaneous regeneration due to their ability to secrete proregenerative cytokines modulating immune response, making them an appreciated option for the treatment of chronic wounds [58]. However, stem cell therapies are limited by the need for invasive harvesting techniques, immunogenicity, and limited cell survival in vivo [59]. Embryonic stem cells (ESCs), induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and adult stem cells are among the main sources of cells that have been used in various experimental research for wound treatment and regeneration of injured skin [60].

4.1. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells

4.2. Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells

4.3. Adipose-Derived Stromal/Stem Cells

5. Immunomodulatory Properties of MSCs: ASCs and BMSCs

It is known that MSCs can modulate the immune system and regulate skin tissue regeneration. Importantly, MSCs can mitogen- and allo-activated lymphocyte proliferation [106][107]. This effect is heavily dependent on some factors; for example, MSCs inhibit lymphocyte proliferation mainly via the secretion of TGF-β1, IL-10, HLA-G, nitric oxide, and hepatocyte growth factor, as well as due to the expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO enzyme) [108][109][110]. Further, MSCs secrete trophic factors which are critical for vasculogenesis and angiogenesis, and aid tissue regeneration [111][112]. Additionally, MSCs have been administrated to the site of wound in animal models by encapsulation in gelatin microspheres and microcryogels or loading into a 3D graphene foam [113]. It has been shown that 3D graphene foam loaded with MSCs released prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), which suppresses the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-12p70, and increases the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and IL-12p40, and TGF-β1 by macrophages [114][115][116]. Additionally, PGE2 reduced the proliferation of T cells in the wound and is a cofactor in the transition from TH1 to TH2 cells, which decrease tissue inflammation and, further, tissue regeneration [115]. Moreover, higher levels of IL-10 expressed by T cells and macrophages in response to PGE2 can limit or reduce the inflammatory mechanism of immune cells. IL-10, which is an important anti-inflammatory cytokine, inhibits further neutrophil invasion and respiratory burst [116]. IL-10 also affects fibrosis by downregulating the release of TGF-β1 in T cells and macrophages, and remodeling ECM by reprogramming wound fibroblasts. IL-10 has direct effects on the prevention of excessive collagen deposition by reducing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-8 in the wound environment [117]. Finally, IL-10 expression results in resolution of inflammatory stage and rushing of the wound into the proliferation stage and over-expression of IL-10 can produce an environment in which wound healing tends to occur without scar formation [118][119][120].

6. Immunomodulatory Skin Scaffolds

Different physical and chemical properties of the biomaterial such as stiffness, topography, roughness, pore size and pore distribution, degradation rate and its debris, surface charge, ligand presentation, and surface functional groups influence the behavior of host cells [135][136]. However, the effects of such biophysical and biochemical characteristics on immune cells, especially when a skin substitute is implanted, are still not elucidated. A biomaterial should be designed to minimize the deleterious host body responses [137][138][139][140][141]. The host immune system response after implantation of an engineered skin substitute is called foreign body reaction (FBR), which can cause significant problems for patients through excessive inflammation and adverse effects on tissue repair processes. Therefore, controlling the biomaterial interaction with the host tissue or FBR is of crucial importance in the field of regenerative medicine and tissue engineering [142][143][144]. In this respect, the term “bioinert implant” refers to any material that is placed in the human body and demonstrates a minimal interaction with its surrounding tissue. Specifically, an acellular fibrous capsule is formed at the interface between tissues and bioinert biomaterials [145]. However, novel biomaterials are being designed to stimulate specific cellular responses at the cellular level to trigger desired immunological outcomes, thereby supporting the wound healing process [146][147].

When a biomaterial is implanted into a vascularized wound bed, the natural innate body response is that plasma proteins are immediately adsorbed onto the implanted biomaterial surface. Factor XII (FXII) and tissue factor (TF) are the initiators of the intrinsic and extrinsic system of the coagulation cascade, respectively, leading to the formation of a blood clot. This leads to infiltration and adherence of cells such as platelets, monocytes, and macrophages through the interaction of adhesion receptors with the adsorbed proteins [146][148]. Adhered cells release growth factors and chemokines, which are able to recruit cells of the innate immune system to the injury/implantation site. Finally, deposition and organization of collagen matrix arise from fibroblasts and MSC activities [149].

| Hydrogel Type | Main Characteristic | Immunomodulatory Role in Skin Regeneration | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decellularized ECM | Containing proteins, glycoproteins, and polysaccharides | Binding to the specific surface receptors of immune cells, the ECM composition can affect immunomodulation, promoting anti-inflammatory phenotype polarization in some cases | [149][160][161][162] |

| Collagen | Protein-based material and the most abundant ECM component | Binding to LAIR-1 receptors on immune cells, suppressing immune cell activity, and resolving post-wound inflammation | [163][164] |

| Fibrin | The main component of the haemostatic clot | Decreasing TNF-α cytokine secretion, decreasing macrophage motility, reduction of neutrophil recruitment, and extending pro-healing effects | [165][166][167][168][169] |

| Hyaluronic acid | Glycosaminoglycans material with various MWs | Modulation of leukocyte function, immunomodulatory effect dependent on MW, suppressing immune cell activity by high-MW HA, enhancing an inflammatory by low-MW HA, delaying inflammation by High-MW HA | [170][171] |

| Chitosan | A natural polysaccharide | Employing leukocytes and macrophages to the wound site, decreasing the inflammatory cells, and TNF-α and MMP-9 levels, and affecting macrophage polarization | [172][173][174][175] |

| Carrageenan | A natural marine polysaccharide from red seaweed | Stimulating IL-10 expression, prohibiting cytotoxic T cell responses, and delaying neutrophil activation | [176][177][178] |

| L-arginine | Amino acid-based material | Decreasing nitric oxide production, stimulating macrophages to express both TNF-α and NO in combination with chitosan | [179][180][181] |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biomedicines10010118

References

- Vig, K.; Chaudhari, A.; Tripathi, S.; Dixit, S.; Sahu, R.; Pillai, S.; Dennis, V.A.; Singh, S.R. Advances in Skin Regeneration Using Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 789.

- Gaur, M.; Dobke, M.; Lunyak, V.V.; Piatelli, A.; Zavan, B. Molecular Sciences Mesenchymal Stem Cells from Adipose Tissue in Clinical Applications for Dermatological Indications and Skin Aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 208.

- Roupé, K.; Nybo, M.; Sjöbring, U.; Alberius, P. Injury is a major inducer of epidermal innate immune responses during wound healing. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2010, 130, 910. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022202x15347771 (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Klar, A.S.; Güven, S.; Biedermann, T.; Luginbühl, J.; Böttcher-Haberzeth, S.; Meuli-Simmen, C.; Meuli, M.; Martin, I.; Scherberich, A.; Reichmann, E. Tissue-engineered dermo-epidermal skin grafts prevascularized with adipose-derived cells. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 5065–5078.

- Böttcher-Haberzeth, S.; Klar, A.S.; Biedermann, T.; Schiestl, C.; Meuli-Simmen, C.; Reichmann, E.; Meuli, M. “Trooping the color”: Restoring the original donor skin color by addition of melanocytes to bioengineered skin analogs. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2013, 29, 239–247.

- Klar, A.S.S.; Böttcher-Haberzeth, S.; Biedermann, T.; Clemens, S.; Ernst, R.; Meuli, M. Analysis of blood and lymph vascularization patterns in tissue-engineered human dermo-epidermal skin analogs of different pigmentation. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2014, 30, 223–231.

- Tavakoli, S.; Klar, A.S. Bioengineered Skin Substitutes: Advances and Future Trends. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1493.

- Klar, A.S.; Güven, S.; Zimoch, J.; Zapiórkowska, N.A.; Biedermann, T.; Böttcher-Haberzeth, S.; Meuli-Simmen, C.; Martin, I.; Scherberich, A.; Reichmann, E.; et al. Characterization of vasculogenic potential of human adipose-derived endothelial cells in a three-dimensional vascularized skin substitute. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2016, 32, 17–27.

- Klar, A.S.; Böttcher-Haberzeth, S.; Biedermann, T.; Michalak, K.; Kisiel, M.; Reichmann, E.; Meuli, M. Differential expression of granulocyte, macrophage, and hypoxia markers during early and late wound healing stages following transplantation of tissue-engineered skin substitutes of human origin. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2014, 30, 1257–1264.

- Zimoch, J.; Padial, J.; Klar, A. Polyisocyanopeptide hydrogels: A novel thermo-responsive hydrogel supporting pre-vascularization and the development of organotypic structures. Acta Biomater. 2018, 70, 129–139. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1742706118300539 (accessed on 29 November 2020).

- Halim, A.; Khoo, T.; Yussof, S. Biologic and synthetic skin substitutes: An overview. Indian J. Plast Surg. 2010, 43, S23–S28.

- Klar, A.S.; Zimoch, J.; Biedermann, T. The Use of Adipose Derived Cells for Skin Nerve Regeneration-Short Review of Experimental Research. J. Tissue Sci. Eng. 2017, 8, 2.

- Shevchenko, R.V.; James, S.L.E.; James, S.L.E. A review of tissue-engineered skin bioconstructs available for skin reconstruction. J. R. Soc. Interface 2010, 7, 229–258.

- Vacanti, J.; Lancet, R.L. Tissue engineering: The design and fabrication of living replacement devices for surgical reconstruction and transplantation. Lancet 1999, 354, 32–34. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(99)90247-7/fulltext (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Chen, M.; Przyborowski, M. Stem cells for skin tissue engineering and wound healing. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2009, 37, 399–421.

- Klar, A.; Zimoch, J.; Biedermann, T. Skin tissue engineering: Application of adipose-derived stem cells. Biomed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 9747010. Available online: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2017/9747010/abs/ (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Tavakoli, S.; Klar, A.S. Advanced Hydrogels as Wound Dressings. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1169.

- Metcalfe, A.D.; Ferguson, M. Bioengineering skin using mechanisms of regeneration and repair. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 5100–5113. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0142961207005601 (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Metcalfe, A.D.; Ferguson, M.W.J. Tissue engineering of replacement skin: The crossroads of biomaterials, wound healing, embryonic development, stem cells and regeneration. J. R. Soc. Interface 2007, 4, 413–417.

- Clayton, K.; Vallejo, A.F.; Davies, J.; Sirvent, S.; Polak, M.E. Langerhans cells-programmed by the epidermis. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1676.

- MA Nilforoushzadeh Dermal Fibroblast Cells: Biology and Function in Skin Regeneration. J. Ski. 2017. Available online: https://sites.kowsarpub.com/jssc/articles/69080.html (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Dhivya, S.; Padma, V. Wound dressings–a review. Biomedicine 2015, 5, 22. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmc4662938/ (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Moore, K.; McCallion, R.; Searle, R.J.; Stacey, M.C.; Harding, K.G. Prediction and monitoring the therapeutic response of chronic dermal wounds. Int. Wound J. 2006, 3, 89–98.

- Lazarus, G.S.; Cooper, D.M.; Knighton, D.R.; Margolis, D.J.; Percoraro, R.E.; Rodeheaver, G.; Robson, M.C. Definitions and guidelines for assessment of wounds and evaluation of healing. Wound Repair Regen. 1994, 2, 165–170.

- Boateng, J.S.; Matthews, K.H.; Stevens, H.N.E.; Eccleston, G.M. Wound healing dressings and drug delivery systems: A review. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 97, 2892–2923.

- Percival, N.J. Classification of Wounds and their Management. Surgery 2002, 20, 114–117.

- Singer, A.J.; Clark, R.A.F. Cutaneous Wound Healing. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 738–746.

- Larson, B.J.; Longaker, M.T.; Lorenz, H.P. Scarless fetal wound healing: A basic science review. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010, 126, 1172–1180.

- Käser, S.A.; Zengaffinen, R.; Uhlmann, M.; Glaser, C.; Maurer, C.A. Primary wound closure with a Limberg flap vs. secondary wound healing after excision of a pilonidal sinus: A multicentre randomised controlled study. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2014, 30, 97–103.

- Burns, P.S. Burn wound healing and skin substitutes. Burns 2001, 27, 517–522. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305417901000171 (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Martin, P. Wound Healing-Aiming for Perfect Skin Regeneration. Science 1997, 276, 75–81. Available online: http://www.sciencemag.org (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Wallace, H.; Basehore, B.; Zito, P. Wound Healing Phases; StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL) 2020. Available online: https://europepmc.org/books/n/statpearls/article-34001/ (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Kloc, M.; Ghobrial, R.M.; Wosik, J.; Lewicka, A.; Lewicki, S.; Kubiak, J.Z. Macrophage functions in wound healing. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2019, 13, 99–109.

- Gilmore, M.A. Phases of wound healing. Dimens Oncol. Nurs. 1991, 5, 32–34. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1823567 (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Wilgus, T.A.; Roy, S.; McDaniel, J.C. Neutrophils and Wound Repair: Positive Actions and Negative Reactions. Adv. Wound Care 2013, 2, 379–388.

- Iacob, A.T.; Drăgan, M.; Ionescu, O.M.; Profire, L.; Ficai, A.; Andronescu, E.; Confederat, L.G.; Lupașcu, D. An Overview of Biopolymeric Electrospun Nanofibers Based on Polysaccharides for Wound Healing Management. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 983.

- McCartney-Francis, N.L.; Wahl, S.M. TGF-β and macrophages in the rise and fall of inflammation. In TGF-β and Related Cytokines in Inflammation; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2001; pp. 65–90.

- Turner, M.; Nedjai, B.; Hurst, T. Cytokines and chemokines: At the crossroads of cell signalling and inflammatory disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1843, 2563–2582. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167488914001967 (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Werner, S.; Krieg, T.; Smola, H. Keratinocyte–fibroblast interactions in wound healing. Keratinocyte–Fibroblast Interact. Wound Health 2007, 127, 998–1008. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022202X15333820 (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Nelson, E.A. Nutrition for optimum wound healing. Nurs. Stand. 2003, 18, 55–58.

- Gordillo, G.M.; Sen, C.K. Revisiting the essential role of oxygen in wound healing. Am. J. Surg. 2003, 186, 259–263.

- Branton, M.H.; Kopp, J.B. TGF-β and fibrosis. Microbes. Infect. 1999, 1, 1349–1365. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1286457999002506 (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Phan, S.H. Biology of Fibroblasts and Myofibroblasts. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2008, 5, 334.

- Van De Water, L.; Varney, S.; Tomasek, J.J. Mechanoregulation of the Myofibroblast in Wound Contraction, Scarring, and Fibrosis: Opportunities for New Therapeutic Intervention. Adv. Wound Care 2013, 2, 122–141.

- Darby, I.; Laverdet, B. Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in wound healing. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 7, 301–311. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4226391/ (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Basu, A.; Kligman, L.H.; Samulewicz, S.J.; Howe, C.C. Impaired wound healing in mice deficient in a matricellular protein SPARC (osteonectin, BM-40). BMC Cell Biol. 2001, 2, 15.

- Chen, D.; Hao, H.; Fu, X. Insight into reepithelialization: How do mesenchymal stem cells perform? Stem Cells Int. 2016, 3, 1–9. Available online: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/sci/2016/6120173/abs/ (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Santoro, M.M.; Gaudino, G.; Santoro, M.M. Cellular and molecular facets of keratinocyte reepithelization during wound healing. Exp. Cell Res. 2005, 304, 274–286.

- Martins, V.L.; Caley, M.; O’toole, E.A. Matrix metalloproteinases and epidermal wound repair. Cell Tissue Res. 2013, 351, 255–268.

- Nguyen, T.T.; Mobashery, S.; Chang, M. Roles of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Cutaneous Wound Healing. Wound Health New Insights Into Anc. Chall. 2016, 37–71.

- Michopoulou, A.; Bernard, C.; Lyon, U.; Rousselle, P. How do epidermal matrix metalloproteinases support re-epithelialization during skin healing? Artic. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2015, 25, 33–42.

- Pastar, I.; Stojadinovic, O.; Yin, N.C.; Ramirez, H.; Nusbaum, A.G.; Sawaya, A.; Patel, S.B.; Khalid, L.; Isseroff, R.R.; Tomic-Canic, M. Epithelialization in Wound Healing: A Comprehensive Review. Adv. Wound Care 2014, 3, 445–464.

- Krzyszczyk, P.; Schloss, R.; Palmer, A.; Berthiaume, F. The Role of Macrophages in Acute and Chronic Wound Healing and Interventions to Promote Pro-wound Healing Phenotypes. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 419.

- Wynn, T.A.; Vannella, K.M. Macrophages in Tissue Repair, Regeneration, and Fibrosis. Immunity 2016, 44, 450–462.

- Martinez, F.O.; Gordon, S. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: Time for reassessment. F1000Prime Rep. 2014, 6.

- Becker, D.A.J.; McCulloch, E.A.; Till, J.E. Cytological Demonstration of the Clonal Nature of Spleen Colonies Derived from Transplanted Mouse Marrow Cells. Nature 1963, 197, 452–454. Available online: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1038/197452a0.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Siminovitch, L.; McCulloch, E.A.; Till, J.E. The Distribution of Colony-Forming Cells among Spleen Colonies. J. Cell. Comp. Physiol. 1963, 62, 327–336. Available online: https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/2778 (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Duscher, D.; Barrera, J.; Wong, V.; Maan, Z. Stem cells in wound healing: The future of regenerative medicine? A mini-review. Gerontology 2016, 62, 216–225. Available online: https://www.karger.com/Article/Abstract/381877 (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Gorecka, J.; Kostiuk, V.; Fereydooni, A.; Gonzalez, L.; Luo, J.; Dash, B.; Isaji, T.; Ono, S.; Liu, S.; Lee, S.R.; et al. The potential and limitations of induced pluripotent stem cells to achieve wound healing. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 1–10.

- Dash, B.; Xu, Z.; Lin, L.; Koo, A.; Ndon, S.; Berthiaume, F.; Dardik, A.; Hsia, H. Stem Cells and Engineered Scaffolds for Regenerative Wound Healing. Bioengineering 2018, 5, 23.

- Smith, A.G. Embryo-derived stem cells: Of mice and men. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2001, 17, 435–462.

- Martin, G.R. Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. USA 1981, 78, 7634–7638. Available online: https://www.pnas.org/content/78/12/7634.short (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Medvedev, S.P.; Shevchenko, A.I.; Zakian, S.M. Induced pluripotent stem cells: Problems and advantages when applying them in regenerative medicine. Acta Nat. 2010, 2, 18–28. Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/14364038 (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Aoi, T.; Yae, K.; Nakagawa, M.; Ichisaka, T.; Okita, K.; Takahashi, K.; Chibaand, T.; Yamanaka, S. Generation of pluripotent stem cells from adult mouse liver and stomach cells. Science 2008, 321, 699–702. Available online: https://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/500000438912/ (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Hanna, J.; Markoulaki, S.; Schorderet, P. Direct reprogramming of terminally differentiated mature B lymphocytes to pluripotency. Cell 2008, 133, 250–264. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867408004479 (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Kim, J.B.; Zaehres, H.; Wu, G. Pluripotent stem cells induced from adult neural stem cells by reprogramming with two factors, nature.com. Nature 2014, 454, 646–650.

- Eminli, S.; Utikal, J.; Arnold, K.; Jaenisch, R.; Hochedlinger, K. Reprogramming of Neural Progenitor Cells into Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells in the Absence of Exogenous Sox2 Expression. Stem Cells 2008, 26, 2467–2474.

- Takahashi, K.; Tanabe, K.; Ohnuki, M.; Narita, M. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 2007, 131, 861–872. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867407014717 (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Yu, J.; Vodyanik, M.A.; Smuga-Otto, K.; Antosiewicz-Bourget, J.; Frane, J.L.; Tian, S.; Nie, J.; Jonsdottir, G.A.; Ruotti, V.; Stewart, R.; et al. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Lines Derived from Human Somatic Cells. Science 2007, 21, 1917–1920.

- Lian, Q.; Liang, X.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tse, H.-F. Paracrine Mechanisms of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapy: Current Status and Perspectives. Cell Transplant. 2014, 23, 1045–1059.

- Baraniak, P.R.; McDevitt, T.C. Stem cell paracrine actions and tissue regeneration. Regen. Med. 2010, 5, 121–143.

- Açikgoz, G.; Devrim, İ.; Özdamar, Ş. Comparison of Keratinocyte Proliferation in Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Inflamed Gingiva. J. Periodontol. 2004, 75, 989–994.

- Kim, K.L.; Song, S.H.; Choi, K.S.; Suh, W. Cooperation of endothelial and smooth muscle cells derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells enhances neovascularization in dermal wounds. In Proceedings of the Tissue Engineering—Part A; Mary Ann Liebert Inc.: Larchmont, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 19, pp. 2478–2485.

- Clayton, Z.; Tan, R. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cells promote angiogenesis and accelerate wound closure in a murine excisional wound healing model. Biosci. Rep. 2018, 38, BSR20180563. Available online: https://portlandpress.com/bioscirep/article-abstract/38/4/BSR20180563/58358 (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Casqueiro, J.; Casqueiro, J. Infections in patients with diabetes mellitus: A review of pathogenesis. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 16, S27–S36. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3354930/ (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Zhang, J.; Guan, J.; Niu, X.; Hu, G.; Guo, S.; Li, Q.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y. Exosomes released from human induced pluripotent stem cells-derived MSCs facilitate cutaneous wound healing by promoting collagen synthesis and angiogenesis. J. Transl. Med. 2015, 13, 1–14.

- Itoh, M.; Umegaki-Arao, N.; Guo, Z.; Liu, L.; Higgins, C.A.; Christiano, A.M. Generation of 3D Skin Equivalents Fully Reconstituted from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77673.

- Kuzuya, M.; Satake, S.; Esaki, T.; Yamada, K.; Hayashi, T.; Naito, M.; Asai, K.; Iguchi, A. Induction of angiogenesis by smooth muscle cell-derived factor: Possible role in neovascularization in atherosclerotic plaque. J. Cell. Physiol. 1995, 164, 658–667.

- Liubaviciute, A.; Ivaskiene, T.; Biziuleviciene, G. Modulated mesenchymal stromal cells improve skin wound healing. Biologicals 2020, 67, 1–8. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1045105620300932 (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Tencerova, M.; Kassem, M. The bone marrow-derived stromal cells: Commitment and regulation of adipogenesis. Front. Endocrinol. 2016, 7, 127.

- Lecka-Czernik, B.; Rosen, C.J. Energy Excess, Glucose Utilization, and Skeletal Remodeling: New Insights. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2015, 30, 1356–1361.

- Lindner, U.; Kramer, J.; Rohwedel, J.; Schlenke, P. Mesenchymal Stem or Stromal Cells: Toward a Better Understanding of Their Biology? Transfus Med. Hemother. 2010, 37, 75–83.

- Abboud, S. A bone marrow stromal cell line is a source and target for platelet-derived growth factor. Blood 1993, 81, 2547–2553. Available online: https://ashpublications.org/blood/article-abstract/81/10/2547/48656 (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Rocha, B.; Calamia, V.; Mateos, J.; Fernández-Puente, P.; Blanco, F.J.; Ruiz-Romero, C. Metabolic labeling of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells for the quantitative analysis of their chondrogenic differentiation. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 11, 5350–5361.

- Wu, Y.; Wang, J.F.; Scott, P.G.; Tredget, E.E. Bone marrow-derived stem cells in wound healing: A review. Wound Repair Regen. 2007, 15, S18–S26.

- Hao, L.; Wang, J.; Zou, Z.; Yan, G.; Dong, S.; Deng, J. Transplantation of BMSCs expressing hPDGF-A/hBD2 promotes wound healing in rats with combined radiation-wound injury. Gene Ther. 2009, 16, 34–42. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/gt2008133 (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Basiouny, H.; Salama, N. Effect of bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells on healing of induced full-thickness skin wounds in albino rat. Int. J. Stem Cells 2013, 6, 12–25.

- Wu, Y.; Chen, L.; Scott, P.G.; Tredget, E.E. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Enhance Wound Healing Through Differentiation and Angiogenesis. Stem Cells 2007, 25, 2648–2659.

- Dash, N.R.; Dash, S.N.; Routray, P.; Mohapatra, S.; Mohapatra, P.C. Targeting nonhealing ulcers of lower extremity in human through autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Rejuvenation Res. 2009, 12, 359–366.

- Sorrell, J.M.; Caplan, A.I. Topical delivery of mesenchymal stem cells and their function in wounds. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2010, 1, 1–6.

- Orlic, D.; Kajstura, J.; Chimenti, S. Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Nature 2001, 5, 701–705.

- Horwitz, E.M.; Prockop, D.J.; Fitzpatrick, L.A.; Koo, W.W.K.; Gordon, P.L.; Neel, M.; Sussman, M.; Orchard, P.; Marx, J.C.; Pyeritz, R.E.; et al. Transplantability and therapeutic effects of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat. Med. 1999, 5, 309–313.

- Salinas, C.N.; Anseth, K.S. Mesenchymal stem cells for craniofacial tissue regeneration: Designing hydrogel delivery vehicles. J. Dent. Res. 2009, 88, 681–692.

- Bharti, M.; Bhat, I.; Pandey, S.; Shabir, U.; Peer, B.A.; Indu, B.; Abas Rashid Bhat, G.S.K.; Sharma, G.T. Effect of cryopreservation on therapeutic potential of canine bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells augmented mesh scaffold for wound healing in guinea pig. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 121, 109573. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0753332219351959 (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Erben, R.; Scutt, A.; Miao, D. Short-Term Treatment of Rats with High Dose 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Stimulates Bone Formation and Increases the Number of Osteoblast Precursor Cells in Bone. Endocrinology 1997, 138, 4629–4635. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/endo/article-abstract/138/11/4629/2991198 (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Yoshimura, K.; Shigeura, T.; Matsumoto, D.; Sato, T.; Takaki, Y.; Aiba-Kojima, E.; Sato, K.; Inoue, K.; Nagase, T.; Koshima, I.; et al. Characterization of freshly isolated and cultured cells derived from the fatty and fluid portions of liposuction aspirates. J. Cell. Physiol. 2006, 208, 64–76.

- Conese, M.; Annacontini, L.; Carbone, A.; Beccia, E.; Cecchino, L.R.; Parisi, D.; Gioia, S.; Di Lembo, F.; Angiolillo, A.; Mastrangelo, F.; et al. The Role of Adipose-Derived Stem Cells, Dermal Regenerative Templates, and Platelet-Rich Plasma in Tissue Engineering-Based Treatments of Chronic Skin Wounds. Stem Cells Int. 2020, 2020, 7056261.

- Patrikoski, M.; Mannerström, B. Perspectives for clinical translation of adipose stromal/stem cells. Stem Cells Int. 2019, 2019, 1–21. Available online: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/sci/2019/5858247/abs/ (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Ntege, E.; Sunami, H. Advances in regenerative therapy: A review of the literature and future directions. Regen. Ther. 2020, 14, 136–153. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352320420300043 (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Peng, Q.; Alipour, H.; Porsborg, S.; Fink, T.; Zachar, V. Evolution of ASC Immunophenotypical Subsets During Expansion In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. Artic. 2020, 21, 1408.

- Mohamed-Ahmed, S.; Fristad, I.; Lie, S.A.; Suliman, S.; Mustafa, K.; Vindenes, H.; Idris, S.B. Adipose-derived and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells: A donor-matched comparison. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 1–15.

- Yu, G.; Wu, X.; Dietrich, M.A.; Polk, P.; Scott, L.K.; Ptitsyn, A.A.; Gimble, J.M. Yield and characterization of subcutaneous human adipose-derived stem cells by flow cytometric and adipogenic mRNA analyzes. Cytotherapy 2010, 12, 538–546.

- Gimble, J.M.; Katz, A.J.; Bunnell, B.A. Adipose-derived stem cells for regenerative medicine. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 1249–1260.

- Gimble, J.; Design, M.N. Adipose-derived stromal/stem cells (ASC) in regenerative medicine: Pharmaceutical applications. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011, 17, 332–339. Available online: https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/ben/cpd/2011/00000017/00000004/art00003 (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Rodriguez, J.; Pratta, A.; Abbassi, N.; Fabre, H. Evaluation of three devices for the isolation of the stromal vascular fraction from adipose tissue and for ASC culture: A comparative study. Stem Cells Int. 2017, 2017.

- Aggarwal, S.; Pittenger, M.F. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses. Blood 2004, 105, 1815–1822.

- di Nicola, M.; Carlo-Stella, C.; Magni, M.; Milanesi, M.; Longoni, P.D.; Matteucci, P.; Grisanti, S.; Gianni, A.M. Human bone marrow stromal cells suppress T-lymphocyte proliferation induced by cellular or nonspecific mitogenic stimuli. Blood 2002, 99, 3838–3843.

- Castro-Manrreza, M.; Montesinos, J. Immunoregulation by Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Biological Aspects and Clinical Applications. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 2015, 394917.

- Krampera, M.; Glennie, S.; Dyson, J.; Scott, D.; Laylor, R.; Simpson, E.; Dazzi, F. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells inhibit the response of naive and memory antigen-specific T cells to their cognate peptide. Blood 2003, 101, 3722–3729.

- Meisel, R.; Zibert, A.; Laryea, M.; Göbel, U.; Däubener, W.; Dilloo, D.; Gö, U.; Dä, W. Human bone marrow stromal cells inhibit allogeneic T-cell responses by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-mediated tryptophan degradation. Blood 2004, 103, 4619–4621.

- Rhijn, M.R.; Reinders, M. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from adipose tissue are not affected by renal disease. Kidney Int. 2012, 82, 748–758. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0085253815556329 (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Tögel, F. Mesenchymal stem cells: A new therapeutic tool for AKI. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2010, 6, 179–183. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrneph.2009.229?cacheBust=1509357641367 (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Rahimnejad, M.; Derakhshanfar, S.; Zhong, W. Biomaterials and tissue engineering for scar management in wound care. Burn. Trauma 2017, 5, 4.

- Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Yang, B.; Sun, Y. Three-dimensional graphene foams loaded with bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells promote skin wound healing with reduced scarring. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2015, 1, 181–188. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0928493115302484 (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Maggini, J.; Mirkin, G.; Bognanni, I.; Holmberg, J.; Piazzón, I.M.; Nepomnaschy, I.; Costa, H.; Cañones, C.; Raiden, S.; Vermeulen, M.; et al. Mouse bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells turn activated macrophages into a regulatory-like profile. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9252.

- Jackson, W.M.; Nesti, L.J.; Tuan, R.S. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for attenuation of scar formation during wound healing. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2012, 3, 20.

- Moore, K.W.; De Waal Malefyt, R.; Coffman, R.L.; O’Garra, A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2001, 19, 683–765.

- Liechty, K.; Kim, H.; Adzick, N.S. Fetal wound repair results in scar formation in interleukin-10–deficient mice in a syngeneic murine model of scarless fetal wound repair. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2000, 35, 866–872. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022346800199518 (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Peranteau, W.; Zhang, L.; Muvarak, N.; Badillo, A.T. IL-10 overexpression decreases inflammatory mediators and promotes regenerative healing in an adult model of scar formation. J. Investig. Dermatol 2008, 128, 1852–1860. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022202×15339464 (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Gordon, A.; Kozin, E.D.; Keswani, S.G.; Vaikunth, S.S.; Katz, A.B.; Zoltick, P.W.; Favata, M.; Radu, A.P.; Soslowsky, L.J.; Herlyn, M.; et al. Permissive environment in postnatal wounds induced by adenoviral-mediated overexpression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 prevents scar formation. Wound Repair Regen. 2008, 16, 70–79.

- Mattar, P.; Bieback, K. Comparing the immunomodulatory properties of bone marrow, adipose tissue, and birth-associated tissue mesenchymal stromal cells. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 560.

- Ceccarelli, S.; Pontecorvi, P. Immunomodulatory Effect of Adipose-Derived Stem Cells: The Cutting Edge of Clinical Application. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 236. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7180192/ (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Cao, C.; Tarlé, S.; Kaigler, D. Characterization of the immunomodulatory properties of alveolar bone-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 120.

- Rostami, Z.; Khorashadizadeh, M.; Letters, M.N. Immunoregulatory properties of mesenchymal stem cells: Micro-RNAs. Immunol. Lett. 2020, 219, 34–45. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165247819305334 (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Wang, M.; Xie, J.; Wang, C.; Zhong, D. Immunomodulatory Properties of Stem Cells in Periodontitis: Current Status and Future Prospective. Stem Cell Int. 2020, 2020, 9836518. Available online: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/sci/2020/9836518/ (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Gonzalez-Rey, E.; Anderson, P.; González, M. Human adult stem cells derived from adipose tissue protect against experimental colitis and sepsis. Gut 2009, 57, 929–939. Available online: https://gut.bmj.com/content/58/7/929.short (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Hong, S.; Traktuev, D.; Organ, K.M. Therapeutic potential of adipose-derived stem cells in vascular growth and tissue repair. Curr. Opin. Organ. Transplant. 2010, 15, 86–91. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/co-transplantation/Fulltext/2010/02000/Cardiac_regeneration_and_stem_cell_therapy.18.aspx (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Jiang, W.; Xu, J. Immune modulation by mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Prolif. 2020, 53, e12712.

- Bartholomew, A.; Sturgeon, C.; Siatskas, M.; Ferrer, K.; McIntosh, K.; Patil, S.; Hardy, W.; Devine, S.; Ucker, D.; Deans, R.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cells suppress lymphocyte proliferation in vitro and prolong skin graft survival in vivo. Exp. Hematol. 2002, 30, 42–48.

- Koppula, P.R.; Chelluri, L.K.; Polisetti, N.; Vemuganti, G.K. Histocompatibility testing of cultivated human bone marrow stromal cells—A promising step towards pre-clinical screening for allogeneic stem cell therapy. Cell. Immunol. 2009, 259, 61–65.

- Mohanty, A.; Polisetti, N.; Vemuganti, G.K. Immunomodulatory properties of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. J. Biosci. 2020, 45, 1–17.

- Cui, L.; Shuo, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, N.; Zhang, W.; Cao, Y. Expanded adipose-derived stem cells suppress mixed lymphocyte reaction by secretion of prostaglandin E2. Tissue Eng. 2007, 13, 1185–1195.

- Gonzalez-Rey, E.; Gonzalez, M.A.; Varela, N.; O’Valle, F.; Hernandez-Cortes, P.; Rico, L.; Büscher, D.; Delgado, M. Human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells reduce inflammatory and T cell responses and induce regulatory T cells in vitro in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 241–248.

- Bertozzi, N.; Simonacci, F. The biological and clinical basis for the use of adipose-derived stem cells in the field of wound healing. Ann. Med. Surg 2017, 20, 41–48. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2049080117302388 (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Mantovani, A.; Biswas, S.K.; Galdiero, M.R.; Sica, A.; Locati, M. Macrophage plasticity and polarization in tissue repair and remodelling. J. Pathol. 2013, 229, 176–185.

- Brown, B.; Ratner, B.; Goodman, S. Macrophage polarization: An opportunity for improved outcomes in biomaterials and regenerative medicine. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 3792–3802. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0142961212002116 (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Williams, D.F. On the mechanisms of biocompatibility. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 2941–2953.

- Li, J.; Hastings, G.W. Oxide bioceramics: Inert ceramic materials in medicine and dentistry. In Handbook of Biomaterial Properties, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 339–352. ISBN 9781493933051.

- Hayashi, K.; Inadome, T.; Tsumura, H. Bone-implant interface mechanics of in vivo bio-inert ceramics. Biomaterials 1993, 14, 1173–1179. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/014296129390163V (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Ehashi, T.; Takemura, T.; Hanagata, N.; Minowa, T.; Kobayashi, H.; Ishihara, K.; Yamaoka, T. Comprehensive genetic analysis of early host body reactions to the bioactive and bio-inert porous scaffolds. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85132.

- Hench, L.L.; Wilson, J. An Introduction to Bioceramics; World Scientific: Singapore, 1993.

- Desai, T. Advances in islet encapsulation technologies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 338–350. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrd.2016.232 (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Onuki, Y.; Bhardwaj, U.; Papadimitrakopoulos, F.; Burgess, D.J. A review of the biocompatibility of implantable devices: Current challenges to overcome foreign body response. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2008, 2, 1003–1015.

- Zakeri Siavashani, A.; Mohammadi, J.; Maniura-Weber, K.; Senturk, B.; Nourmohammadi, J.; Sadeghi, B.; Huber, L.; Rottmar, M. Silk based scaffolds with immunomodulatory capacity: Anti-inflammatory effects of nicotinic acid. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 148–162.

- Hench, L.L.; Thompson, I. Twenty-first century challenges for biomaterials, Royalsocietypublishing.Org. J. R. Soc. Interface 2010, 7, S379–S391.

- Franz, S.; Rammelt, S.; Scharnweber, D.; Simon, J.C. Immune responses to implants—A review of the implications for the design of immunomodulatory biomaterials. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 6692–6709.

- Dziki, J.L.; Huleihel, L.; Scarritt, M.E.; Badylak, S.F. Extracellular Matrix Bioscaffolds as Immunomodulatory Biomaterials. Tissue Eng. Part. A 2017, 23, 1152–1159.

- Anderson, J.; Rodriguez, A. Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. Semin. Immunol. 2008, 20, 86–100. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1044532307000966 (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Badylak, S.F.; Valentin, J.E.; Ravindra, A.K.; McCabe, G.P.; Stewart-Akers, A.M. Macrophage phenotype as a determinant of biologic scaffold remodeling. Tissue Eng. Part. A. 2008, 14, 1835–1842.

- Singh, S.; Awuah, D.; Rostam, H.M.; Emes, R.D.; Kandola, N.K.; Onion, D.; Htwe, S.S.; Rajchagool, B.; Cha, B.H.; Kim, D.; et al. Unbiased Analysis of the Impact of Micropatterned Biomaterials on Macrophage Behavior Provides Insights beyond Predefined Polarization States. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 3, 969–978.

- Corliss, B.A.; Azimi, M.S.; Munson, J.M.; Peirce, S.M.; Murfee, W.L. Macrophages: An Inflammatory Link Between Angiogenesis and Lymphangiogenesis. Microcirculation 2016, 23, 95–121.

- Ashouri, F.; Beyranvand, F.; Boroujeni, N.B.; Tavafi, M.; Sheikhian, A.; Varzi, A.M.; Shahrokhi, S. Macrophage polarization in wound healing: Role of aloe vera/chitosan nanohydrogel. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2019, 9, 1027–1042.

- Kumar, M.; Gupta, P.; Bhattacharjee, S. Immunomodulatory injectable silk hydrogels maintaining functional islets and promoting anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage polarization. Biomaterials 2018, 187, 1–17. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0142961218306823 (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Landén, N.X.; Li, D.; Ståhle, M. Transition from inflammation to proliferation: A critical step during wound healing. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 3861–3885.

- Lucas, T.; Waisman, A.; Ranjan, R. Differential roles of macrophages in diverse phases of skin repair. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 3964–3977. Available online: https://www.jimmunol.org/content/184/7/3964.short (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Klar, A.S.; Michalak-Mićka, K.; Biedermann, T.; Simmen-Meuli, C.; Reichmann, E.; Meuli, M. Characterization of M1 and M2 polarization of macrophages in vascularized human dermo-epidermal skin substitutes in vivo. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2018, 34, 129–135.

- Koh, T.; Medicine, L.D. Inflammation and wound healing: The role of the macrophage. Expert Rev. Mol. 2011, 13, e23. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/expert-reviews-in-molecular-medicine/article/inflammation-and-wound-healing-the-role-of-the-macrophage/9B0BF84E8A239160D32F2EE8214633D3 (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Klar, A.S.A.; Biedermann, T.; Simmen-Meuli, C.; Reichmann, E.; Meuli, M.; Simmen-Meuli, C. Comparison of in vivo immune responses following transplantation of vascularized and non-vascularized human dermo-epidermal skin substitutes. Pediatr. Surg. 2017, 33, 377–382.

- Brown, B.; Londono, R.; Tottey, S.; Zhang, L. Macrophage phenotype as a predictor of constructive remodeling following the implantation of biologically derived surgical mesh materials. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 978–987. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1742706111005344 (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Meng, F.W.; Slivka, P.F.; Dearth, C.L.; Badylak, S.F. Solubilized extracellular matrix from brain and urinary bladder elicits distinct functional and phenotypic responses in macrophages. Biomaterials 2015, 46, 131–140.

- Chakraborty, J.; Roy, S.; Ghosh, S. Regulation of decellularized matrix mediated immune response. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 1194–1215.

- Kharaziha, S.; Baidya, A.; Annabi, N. Rational Design of Immunomodulatory Hydrogels for Chronic Wound Healing. Adv. Mater 2021, 33, 2100176.

- jan Lebbink, R.; Raynal, N.; de Ruiter, T.; Bihan, D.G.; Richard, W.; Farndale, L.M. Identification of multiple potent binding sites for human leukocyte associated Ig-like receptor LAIR on collagens II and III. Matrix Biol. 2009, 28, 202–210. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0945053×09000341 (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- El Masry, M.S.; Chaffee, S.; Ghatak, P.D.; Mathew-Steiner, S.S.; Das, A.; Higuita-Castro, N.; Roy, S.; Anani, R.A.; Sen, C.K. Stabilized collagen matrix dressing improves wound macrophage function and epithelialization. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 2144–2155.

- Amlericani Societlj, C.; Inv, B.; Pathologv, E.; Brown, L.F.; Lanir, N.; McDonagh, J.; Tognazzi, K.; Dvorak, A.M.; Dvorak, H.F. Fibroblast Migration in Fibrin Gel Matrices. Am. J. Pathol. 1993, 142, 273–283.

- Clark, R.A. Fibrin and wound healing. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001, 936, 355–367. Available online: https://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/10017318701/ (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Stone, R.; Natesan, S.; Kowalczewski, C.J.; Mangum, L.H.; Clay, N.E.; Clohessy, R.M.; Carlsson, A.H.; Tassin, D.H.; Chan, R.K.; Rizzo, J.A.; et al. Advancements in regenerative strategies through the continuum of burn care. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 672.

- Hsieh, J.; Smith, T.; Meli, V.; Tran, T. Differential regulation of macrophage inflammatory activation by fibrin and fibrinogen. Acta Biomater. 2017, 1, 14–24. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1742706116304974 (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Qu, Z.; Chaikof, E.L. Interface between hemostasis and adaptive immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2010, 22, 634–642.

- Knopf-Marques, H.; Pravda, M.; Wolfova, L.; Velebny, V.; Schaaf, P.; Vrana, N.E.; Lavalle, P. Hyaluronic Acid and Its Derivatives in Coating and Delivery Systems: Applications in Tissue Engineering, Regenerative Medicine and Immunomodulation. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2016, 5, 2841–2855.

- Rayahin, J.E.; Buhrman, J.S.; Zhang, Y.; Koh, T.J.; Gemeinhart, R.A. High and Low Molecular Weight Hyaluronic Acid Differentially Influence Macrophage Activation. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 1, 481–493.

- Fong, D.; Hoemann, C.D. Chitosan immunomodulatory properties: Perspectives on the impact of structural properties and dosage. Futur. Sci. OA 2018, 4, FSO225.

- Takei, T.; Nakahara, H.; Ijima, H. Synthesis of a chitosan derivative soluble at neutral pH and gellable by freeze–thawing, and its application in wound care. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 686–693. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1742706111004363 (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Porporatto, C.; Bianco, I.D.; Riera, C.M.; Correa, S.G. Chitosan induces different L L-arginine metabolic pathways in resting and inflammatory macrophages. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 304, 266–272.

- Moura, L.I.F.; Dias, A.M.A.; Leal, E.C.; Carvalho, L.; De Sousa, H.C.; Carvalho, E.; Biomaterialia, A.; Moura, L.I.F.; Dias, A.M.A.; Leal, E.C.; et al. Chitosan-based dressings loaded with neurotensin-an efficient strategy to im-prove early diabetic wound healing. Acta Biomater. 2013, 10, 843–857.

- Fitton, J.H.; Stringer, D.N.; Karpiniec, S.S. Therapies from Fucoidan: An Update. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 5920–5946.

- Wijesekara, I.; Pangestuti, R.; Kim, S.K. Biological activities and potential health benefits of sulfated polysaccharides derived from marine algae. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 84, 14–21.

- Kalitnik, A.A.; Anastyuk, S.D.; Sokolova, E.V.; Kravchenko, A.O.; Khasina, E.I.; Yermak, I.M. Oligosaccharides of κ/β-carrageenan from the red alga Tichocarpus crinitus and their ability to induce interleukin 10. J. Appl. Phycol. 2015, 1, 545–553.

- He, M.; Potuck, A.; Zhang, Y.; Chu, C.C. Arginine-based polyester amide/polysaccharide hydrogels and their biological response. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 2482–2494.

- El-Sakka, A.I.; Salabas, E.; Dinçer, M.; Kadioglu, A. The pathophysiology of Peyronie’s disease. Arab J. Urol. 2013, 11, 272–277.

- He, M.; Sun, L.; Fu, X.; McDonough, S.P.; Chu, C.C. Biodegradable amino acid-based poly(ester amine) with tunable immunomodulating properties and their in vitro and in vivo wound healing studies in diabetic rats’ wounds. Acta Biomater. 2019, 84, 114–132.