Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Plant Sciences

An essential oil (EO) is a concentrated hydrophobic liquid containing volatile, easily evaporated at normal temperatures, chemical compounds isolated from plants. Essential oils are also known as volatile oils, ethereal oils, aetheroleum, or simply as the oil of the plant, from which they were extracted. EOs of various species of Lavandula dentata (Lamiaceae) have a broad range of biological effects including sedative, antibacterial, antifungal, antidepressant, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties.

- sustainable

- environmentally friendly

- antiradical

- biofungicide

- bioinsecticide

- pharmaceutical

- insect repellent

1. Introduction

Filamentous fungi are the most common type of pathogenic microorganisms that reduce agricultural productivity and quality and cause major economic losses of crops [1]. Mycotoxigenic fungi are known for their ability to colonize a wide range of cereal grains, vegetables, spices and fruits. This type of mold produces mycotoxins, which are associated with various effects on health of humans, including genotoxicity, carcinogenicity and immunosuppression [2]. Currently, adoption of resistant cultivars and phytosanitary treatments are the main stays of prevention strategies to control infection by fungi [3]. To minimize accumulation of residues in soil and novel fungal races with resistance to chemical treatments, new environmentally friendly, crop protection approaches are required [4]. In this context, essential oils (EOs) offer potential alternatives to synthetic fungicides to improve protection measures against phytopathogenic fungi.

Due to its richness in dietary protein, minerals and vitamins, globally, chickpea (Cicer arietinum) is one of the most nutritious seed legumes for human consumption [5]. Losses of yields of leguminous crops during storage due to various types of insects, especially bruchids, is a serious problem for traders and farmers [6]. Chickpea weevil (Callosobruchus maculatus), is one of the most damaging pests of chickpea. This insect is able to lay eggs both in cultivated fields and storage areas. Its larvae, which feed internally on seeds, are difficult to control with chemical insecticides [5]. Synthetic insecticides are routinely used to control pests in agricultural crops. However, their indiscriminate and excessive usage has led to harmful consequences for human health, environmental pollution, residues of pesticides on fruits, vegetables and seeds, insect pests and weeds resistant to effects of crop protection chemicals. Currently, due to their specificity for agricultural pests, and biodegradability, biopesticides developed from EOs might be a viable option for protecting crops while reducing negative effects of synthetic pesticides [7].

Free radicals are chemical species with a single electron on their peripheral layer resulting from cellular oxidation in mammals. Free radicals can cause cytotoxic consequences and tissue lesions and also damage DNA. In order to defend itself, the human body needs antioxidant agents that neutralize these free radicals. Plants, through their secondary metabolites, provide powerful antioxidant agents to control and mitigate the harms of free radicals [8].

Recently, EOs produced from aromatic plants have attracted interest because of their many biological actions [9]. An EO is a concentrated hydrophobic liquid containing volatile, easily evaporated at normal temperatures, chemical compounds isolated from plants. Essential oils are also known as volatile oils, ethereal oils, aetheroleum, or simply as the oil of the plant, from which they were extracted. EOs of various species of Lavandula dentata (Lamiaceae) have a broad range of biological effects including sedative, antibacterial, antifungal, antidepressant, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [10]. Due to its major terpenic components, such as linalool, camphor, eucalyptol, and linalyl acetate, these essences have also demonstrated considerable success for control of insects [7]. However, there is a lack of information and research on other bioactivities of EOs from the Moroccan variety of L. dentata, especially for insect pests in agriculture and some phytopathogenic fungi. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to characterize and assess antioxidant capacity and antifungal activity of EOs isolated from the aerial parts of L. dentata, against some phytopathogenic fungi implicated in contamination of leguminous products. The study also investigated insecticidal activity of EOs of this emblematic Moroccan plant pharmacopoeia against the chickpea weevil.

2. Yield of Essential Oil

3. Physical Parameters of the Essential Oil

Physical properties of L. dentata EO were used as parameters of quality according to recommendations set by the European Pharmacopoeia [12]. All parameters investigated complied with AFNOR standards (Table 1). This reflects the efficiency of the hydro-distillation method used.

Table 1. Physical parameters of L. dentata EO compared to AFNOR standards.

| Physical Parameters | Essential Oils | AFNOR Standards |

|---|---|---|

| Relative density at 20 °C | 0.899 | 0.891 ≤ d ≤ 0.899 |

| Refractive index at 20 °C | 1.463 | 1.463 ≤ n ≤ 1.468 |

| Rotatory power at 20 °C | −3.0° | −7.0° ≤ α ≤ −3.0° |

4. Phytochemical Composition of Essential Oil

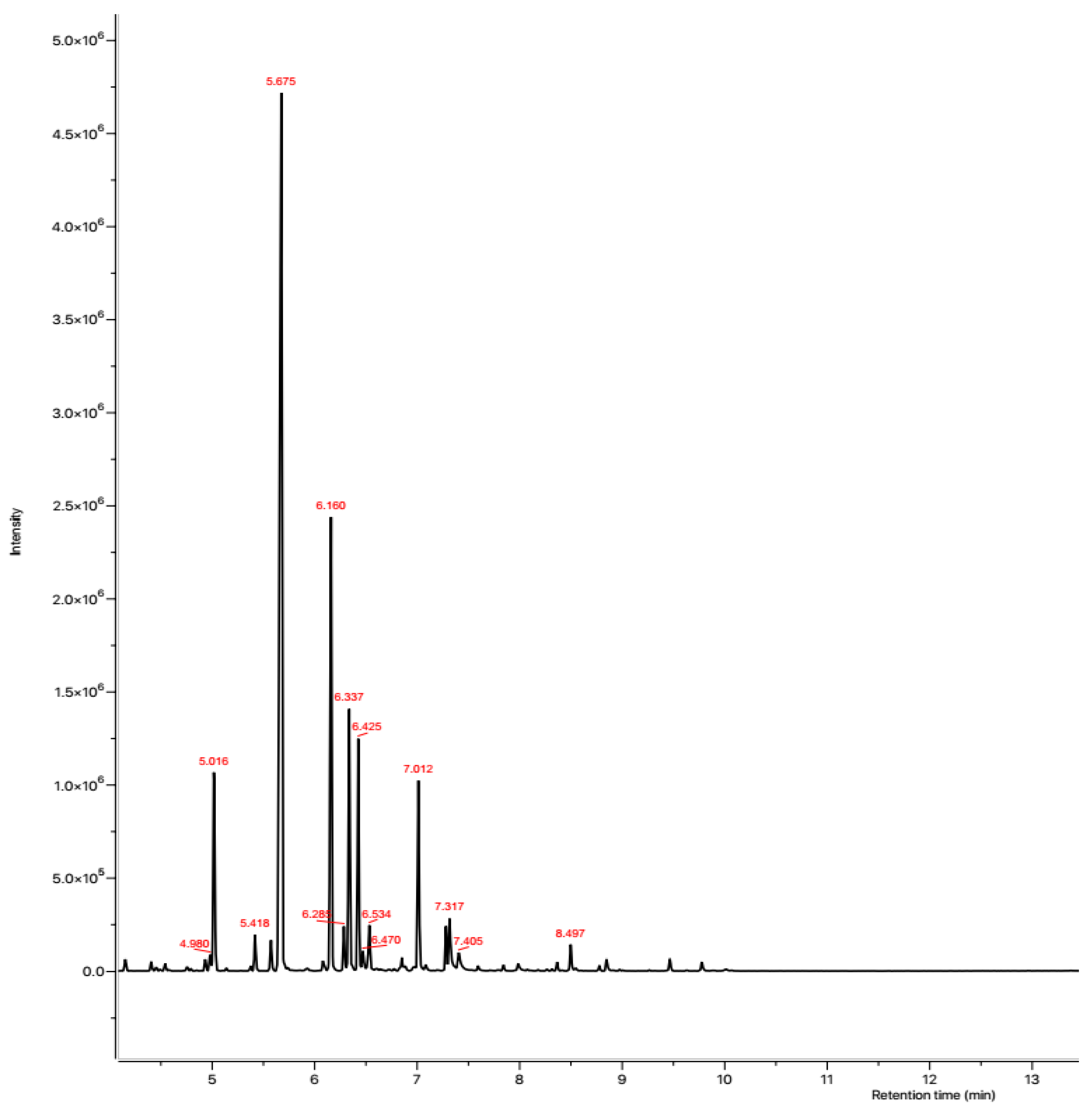

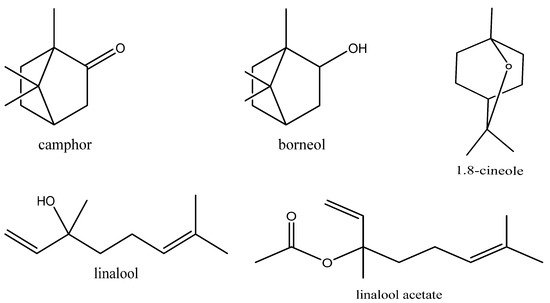

Using GC-FID and GC–MS techniques, the chemical composition of EO extracted from L. dentata was identified and quantified (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Constituents found are summarized in order of times of elution from the HP-5MS column (Table 2). Sixteen compounds were identified in L. dentata EO representing 99.61% of the total essence. The major constituent was linalool (45.06%) followed by camphor (15.62%), and borneol (8.28%), all of which belong to the class of oxygenated monoterpenes that constitute the major class (91.18%) of the studied EO. Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons were represented by only β-farnesene (0.86%) and other compounds comprised 7.57% of the EO of lavender. Other chemotypes of Moroccan lavender have been previously investigated. The 1,8 cineol (41.28%) was the major compound of L. dentata from eastern Morocco [13], while lavender collected from the Moroccan middle Atlas was rich in Camphor (49.75%) [14]. In Tunisia, EO extracted from leaves of L. dentata were rich in camphor (26.52%) and 1,8 cineole (22.90%) [15]. The 1,8 cineole was also observed to be a major constituent of lavender cultivated in Brazil (63.25%) [16], and in Italy (69.08%) [17]. These differences can be attributed to seasonal conditions, circadian rhythms, and environmental influences [16]. Some compounds in characterized EO including linalool, camphor, borneol, thymol and carvacrol are potentially bioactive with multiple pharmacological activities [18].

Figure 1. GC-MS chromatographic profile of L. dentata EO.

Figure 2. Molecular structure of phytochemical compounds of some molecules in L. dentata EO.

Table 2. Phytochemical compounds of the EO extracted from L. dentata.

| Peak | RT | Compounds | Chemical Classes | RI | Area (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cal | Lit | |||||

| 1 | 4.98 | Limonene | Monoterpene (MT) | 1028 | 1029 | 0.58 |

| 2 | 5.01 | 1,8-Cineole | MT | 1030 | 1031 | 7.24 |

| 3 | 5.41 | Cis-Linalool oxide | MT | 1070 | 1072 | 1.08 |

| 4 | 5.57 | Trans-Linalooloxide | MT | 1085 | 1086 | 1.06 |

| 5 | 5.67 | Linalool | MT | 1090 | 1090 | 45.06 |

| 6 | 6.16 | Camphor | MT | 1145 | 1146 | 15.62 |

| 7 | 6.28 | Lavandulol | MT | 1160 | 1161 | 1.22 |

| 8 | 6.33 | Borneol | MT | 1168 | 1169 | 8.28 |

| 9 | 6.42 | γ-Terpineol | MT | 1166 | 1166 | 7.01 |

| 10 | 6.47 | Hexenyl butanoate | Other (O) | 1185 | 1186 | 0.47 |

| 11 | 6.53 | α-Terpineol | MT | 1198 | 1199 | 1.54 |

| 12 | 7.01 | Linalool acetate | O | 1233 | 1234 | 6.01 |

| 13 | 7.28 | Lavandulyl acetate | O | 1290 | 1290 | 1.09 |

| 14 | 7.31 | Thymol | MT | 1290 | 1290 | 1.68 |

| 15 | 7.40 | Carvacrol | MT | 1298 | 1299 | 0.81 |

| 16 | 8.49 | β-Farnesene | Sesquiterpene (ST) | 1441 | 1442 | 0.86 |

| Chemical Classes(% by mass) | ||||||

| Monoterpene (MT) | 91.18 | |||||

| Sesquiterpene (ST) | 0.86 | |||||

| Others (O) | 7.57 | |||||

| Total | 99.61 | |||||

RT = Retention time in minutes; RI = Retention indices; Cal = Calculate; Lit = Literature.

5. In Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Essential Oil

Antioxidant properties of L. dentata EO were assessed using DPPH scavenging, FRAP, and phosphomolybdenum tests (Table 3). When the DPPH test was conducted to evaluate the hydrogen-donating or radical-scavenging potential of the EO in the presence of 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) stable radical as a reagent, the concentration of EO that caused a 50% inhibition (IC50) of the free radical was 12,950 ± 1300 mg EO/mL. The IC50 of the studied oil was significantly (p < 0.001) lesser than the value of the reference antioxidant (BHT), which had an IC50 value of 0.134 ± 0.028 mg/mL.

Table 3. Antioxidant activities of L. dentata EO (means ± SD).

| DPPH (IC50 mg/mL) | FRAP (EC50 mg/mL) | TAC (mg AAE/g EO) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Essential oil | 12.950 ± 1.300 a | 11.880 ± 0.225 a | 81.280 ± 2.278 a |

| BHT | 0.134 ± 0.028 b | 0.362 ± 0.010 b | 47.540 ± 1.200 b |

| Quercetin | - | 0.032 ± 0.003 c | 28.390 ± 1.248 c |

Values with different letters (a, b or c) in each column are significantly different (p < 0.05).

Essential oils are mixtures of several volatile and semi-volatile compounds with various polarity and functional groups, which results in a variety of chemical behaviors. Depending on the test utilized, these mixtures might give different results. It was, therefore, necessary to use a multi-assay approach to assess antioxidant ability of EO studied. In this regard, Results of the TAC test showed that the total antioxidant capacity of EO and reference antioxidants (BHT and quercetin) expressed as ascorbic acid equivalents (mg AAE/g EO) were 81.280 ± 2.278 mg/mL, 47.540 ± 1.200 mg/mL and 28.390 ± 1.248 mg/mL respectively (Table 3).

In the present study, the antioxidant potential was also assessed utilizing the FRAP assay (Table 3). Lavender EO were able to reduce Fe3+ to Fe2+ with an EC50 value of 11.880 ± 0.225 mg/mL, but this reducing capacity was found significantly (p < 0.001) less potent than those of the synthetic antioxidants BHT and quercetin with an EC50 values of 0.362 ± 0.010 mg/mL and 0.032 ± 0.003 mg/mL respectively.

Findings of the study, results of which are reported here, were compared with those published in previously, all of which exhibited lesser antioxidant potencies for L. dentata EOs based on various assays [2][16][19]. Several studies conducted on other species belonging to the genus Lavandula reported a significant antioxidant potential in the case of L. pedunculata, L. stoechas and L. officinalis [20][21]. Moderate antioxidant potential of the EO extracted from L. dentata is probably due to the complex mixture of compounds it contains and to the large proportion of oxygenated compounds (91.18%). Furthermore, unsaturated compounds, especially those with more than one hydroxyl group are more involved in antioxidant processes of lavender, in particular the ability to reduce the free radical DPPH [16]. Several studies conducted on antioxidant potencies of several compounds suggested that linalool and 1,8 cineole, which are major constituents of the lavender EOs, exhibited a moderate antioxidant potential compared to carvacrol, which is a minor compound in EOs of lavender [22]. Similar work has reported that linalool performs through several assays a stronger antioxidant potential compared to 1.8 cineole, camphor, borneol and terpinen-4-ol. While thymol and carvacrol were the strongest in terms of antioxidant activity [18]. Consequently, this diversity of chemicals from the studied EO, in addition to their potential action mode and interactions, make it difficult to attribute antioxidant effect to one or a few active compounds. Antioxidants can exhibit a wide range of biological effects, including anti-atherogenic, anti-allergic, antimicrobial, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory and their quantification and identification can be considered an important step to discover biological and chemical properties of this natural compounds [23].

6. Antifungal Activity of Essential Oil

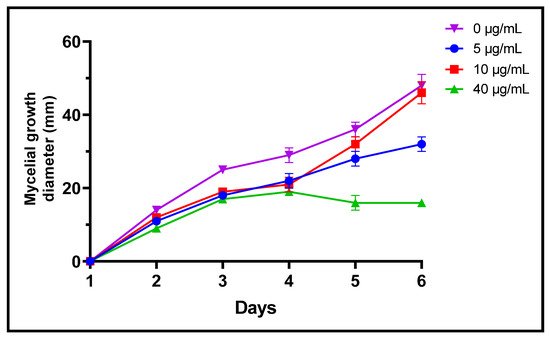

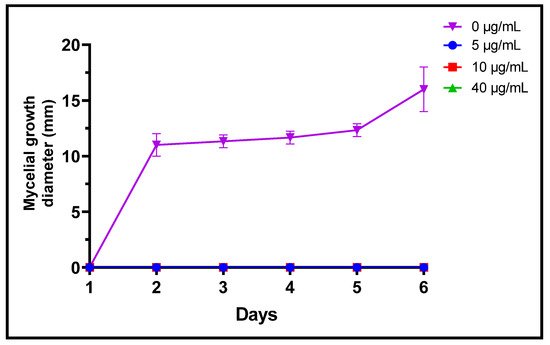

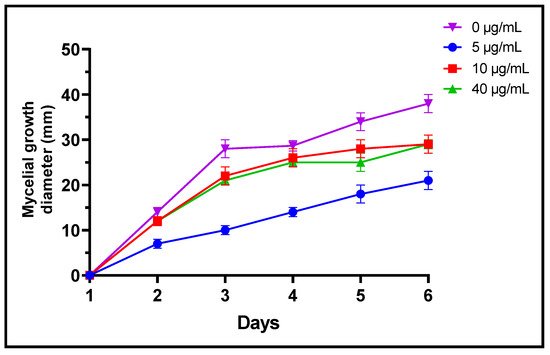

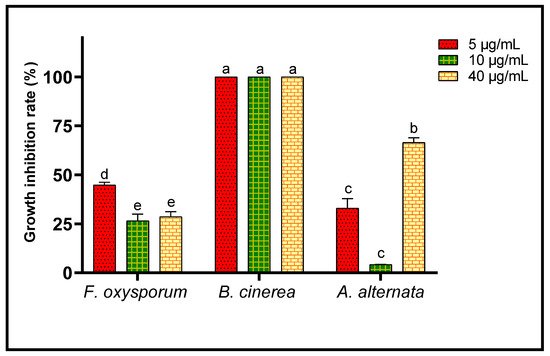

Fungi are frequently implicated in the contamination of fruit and legume crops during harvest or storage, which is the case for the genera Fusarium, Alternaria and Botrytis [24]. These mycotoxin-producing filamentous molds are pathogenic and constitute a real danger to human health [2]. In the present study, three different concentrations of L. dentata EO were tested to evaluate, in vitro, their antifungal effects on growth of B. cinerea, A. alternata and F. oxysporum on Czapek-Dox agar medium (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). Lavender EO exerted various antifungal actions on growth of the studied fungi and inhibited its mycelial growth in a dose dependent manner. During the entire incubation time, L. dentata oil totally inhibited B. cinerea mycelial growth at all doses tested. Oil concentrations of 5 and 10 μg/mL were ineffective against A. alternata mycelial growth, while the concentration of 40 μg/mL showed partial antifungal activity. Against F. oxysporum, all three concentrations, especially 5 μg/mL, exhibited an inhibitory effect compared to the control, by retarding the mycelial growth kinetics of the fungus, which started on the second day.

Figure 3. Mycelial growth kinetic of A. alternata treated by three concentrations of L. dentate EO.

Figure 4. Mycelial growth kinetic of B. cinerea treated by three concentrations of L. dentata EO.

Figure 5. Mycelial growth kinetic of F. oxysporum treated by three concentrations of L. dentata EO.

Inhibition of growth of the three fungal strains studied was calculated after the 6th day of incubation for all concentrations of EO studied (Figure 6). B. cinerea seems to be the most sensitive to lavender EO, since growth of that fungus was completely (100%) inhibited. F. oxysporum and A. alternata were less sensitive to inhibition by EO of L. dentata, but growths of these fungi were partially inhibited. Thus, after 6 days of incubation, 40 μg/mL of the EO inhibited A. alternata growth up to 66.48 ± 2.41%. The same oil inhibited growth of mycelium of F. oxysporum by 44.81 ± 1.36% at a concentration of 5 μg/mL. The IC50 value corresponding to the EO concentration responsible for 50% inhibition of mycelial growth, after the 6th day of incubation, was also calculated for F. oxysporum (23.95 ± 2.83 μg/mL), whereas it was incalculable in the case of B. cinerea and A. alternate.

Figure 6. Growth inhibition rate of A. alternata, B. cinerea and F. oxysporum after the 6th day of treatment by three concentrations of L. dentata EO. For every fungal strain values with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05).

Results of this study are better than those in which exposure to 1 mg L. dentata EO/mL inhibited growth of mycelia of A. alternata and S. cucurbitacearum by 54% and 73.92% respectively [1] with higher IC50 values of 893 μg/mL and 389 μg/mL, respectively. It has been reported also that a concentration of 0.1% of L. dentata EO inhibited mycelium growth of A. carbonarius by 63.7% [2]. Results of other studies have shown that a concentration of 60 μL/disc of EO extracted from L. stoechas inhibited mycelium extensions of F. oxysporum and R. solani by 71.3–76.6% and 100%, respectively [25]. Antifungal effects of Eos are related to their chemical compositions. Potential individual or synergetic effects between the major and minor compounds can occur. Linalool, borneol, 1,8-cineole and camphor, which are major constituents of L. dentata EO, might be responsible for the observed fungicidal action. Results of other studies have indicated that linalool followed by 1,8-cineole have a strong toxic effect against growth of mycelia of A. pullulans, D. hansenii and four fungi of the genus Penicillium [22]. Furthermore, growth of mycelia and germination of spores of Botrytis cinerea in vitro were strongly reduced by application of carvacrol and thymol, which are minor constituents of the lavender EO studied here [26]. Consequently, this diversity of chemicals present in the studied EO, in addition to their various antifungal potency, make it difficult to attribute the antifungal action to one or more active components. Different mechanisms have been reported to explain the toxicity of EOs against fungi. Indeed, the lavender antifungal effect could be related to EO terpenes and phenolic chemicals, which are known to damage cell membranes, causing leakage of cellular materials, and responsible for the inhibition of electron transport and ATPase in the mitochondria and ultimately the microorganism death [27]. In closer works, it was stated that some EOs reduced significantly the production of the phospholipase enzyme produced by C. albicans strains decreasing strongly its virulence [28].

7. Insecticidal Activity of Essential Oil

7.1. Toxicity of Essential Oil against C. maculatus

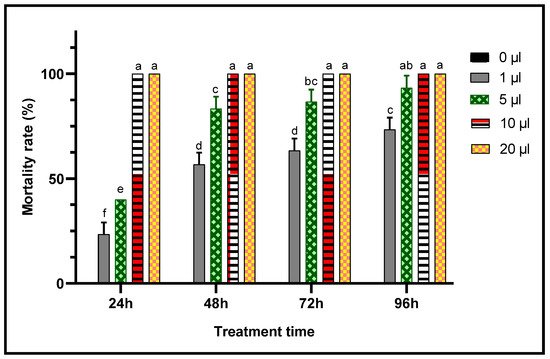

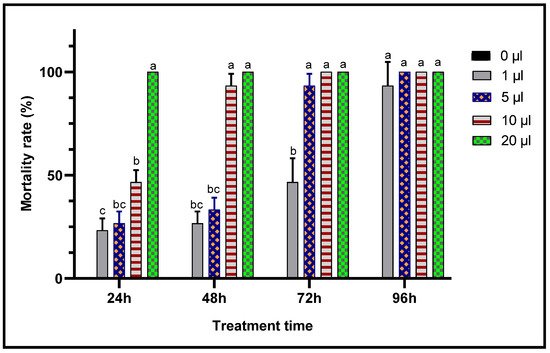

When toxic potencies of L. dentata EO against C. maculatus adults was studied through two inhalation and contact tests to evaluate their insecticidal activity against this chickpea pest, lavender EO exhibited a very significant insecticidal effects in both contact and inhalation tests (Figure 7 and Figure 8). In fact, mortality of adult C. maculatus increased with greater doses of EO and durations of exposure. The least concentration (1 μL/L) of EO of L. dentata caused lethality 23.33 ± 5.77% of adult C. maculatus, in both tests studied. Mortality increased considerably (p < 0.05) with the duration of exposure up to 96 h. At greater concentrations, total mortality (100%) was observed from the first 24 h in chickpea bruchid adults treated with 10 μL/L and 20 μL/L of the EO in contact and inhalation tests respectively. No mortality (0%) was observed in the control jar.

Figure 7. Mortality (means ± SD) of C. maculatus adults exposed to a contact toxicity test of different concentrations of L. dentata EO. Values with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05).

Figure 8. Mortality (means ± SD) of C. maculatus adults exposed to an inhalation toxicity test of different concentrations of L. dentata EO. Values with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05).

Concentrations of the lavender EO that cause 50% (LC50) and 95% (LC95) mortality in C. maculatus adults during 24 h were also calculated (Table 4). The biocide effect was more important in the case of the contact test, for which the LC50 (LC50 = 4.01 μL/L air) was less than during the inhalation test (LC50 = 5.90 μL/L air).

Table 4. LC50 and LC95 (μL/L air) responsible of mortality of C. maculatus adults in contact and inhalation toxicity tests after 24 h treatment with L. dentata EO.

| Bioassays | LC50 (μL/L Air) | LC95 (μL/L Air) | Chi-Square (X2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhalation test | 05.90 | 74.83 | 64.68 |

| Contact test | 04.01 | 16.48 | 62.80 |

7.2. Effects of Essential Oil on Fecundity and Emergence of C. maculatus

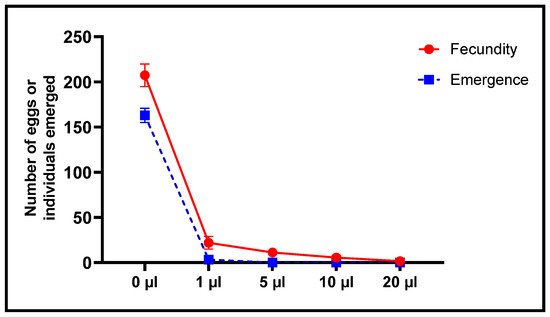

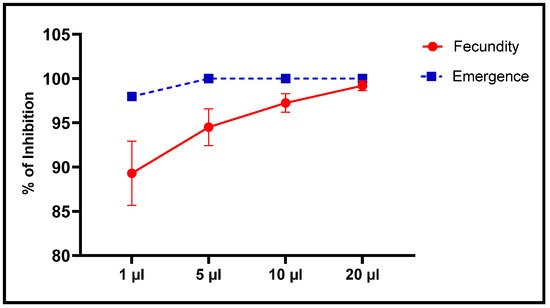

When effects of L. dentata EO on oviposition by females and emergence of new C. maculatus individuals were also studied, the number of eggs laid was inversely proportional to concentrations of EO (Figure 9 and Figure 10). The least concentration (1 μL/L), resulted in a decrease in oviposition to 22 ± 7 eggs/female, corresponding to 89.39% lesser fecundity, compared to the control. At the greatest concentration (20 μL/L), mean number of eggs laid per female was significantly less at 1.67 ± 1.15 eggs/female, which is equivalent to 99.2% less oviposition. Mean oviposition of unexposed, female C. maculatus was 207.33 ± 12.5 eggs/female.

Figure 9. Fecundity of females (mean values of eggs laid ± SD) and Emergence (means ± SD) of C. maculatus adults after a direct contact toxicity test with different concentrations of L. dentata EO.

Figure 10. Inhibition of fecundity and emergence (means ± SD) of C. maculatus adults after a direct contact toxicity test with different concentrations of L. dentata EO.

Alternatively, the number of emergences was significantly less in a dose-dependent manner with concentrations of EO to which they were exposed (Figure 9 and Figure 10). At the least concentration of 1 µL EO/L, the number of emergences of C. maculatus individuals after embryonic development in chickpea seeds was 3.33 ± 0.58 individuals compared to 163 ± 7.94 individuals in the control, which corresponds to 97.96% inhibition of emergence. Exposure to 5 µL EO/L resulted in 100% inhibition of emergence of new individuals.

7.3. Repellent Activity of Essential Oil against C. maculatus

When the repellent activity against C. maculatus insects was also tested, the EO of lavender, based on the classification of McDonald (1970), exhibited only moderate repellent activity (Table 5) [29]. The rate of repulsion was dose-dependent with a maximum of 43.33 ± 5.77% observed after 120 min of exposure to the concentration of 0.315 µL/cm2 of the EO and a mean repulsion of 34.44% for the same period.

Table 5. Results of the repellent activity of L. dentata EO against C. maculatus depending on the treatment time.

| Repellent Activity at Different Doses of Essential Oil | PR Average (%) | Class * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.079 (µL/cm2) | 0.157 (µL/cm2) | 0.315 (µL/cm2) | |||

| 30 min | 13.33 ± 5.77 | 20.00 ± 10.00 | 26.67 ± 5.77 | 20.00 | Moderately repellent (II) |

| 60 min | 20.00 ± 10.00 | 33.33 ± 5.77 | 40.00 ± 0.00 | 31.11 | Moderately repellent (II) |

| 120 min | 26.67 ± 5.77 | 33.33 ± 5.77 | 43.33 ± 5.77 | 34.44 | Moderately repellent (II) |

* Class of repellent effect according to the classification of McDonald (1970).

L. dentata EO exhibited significant insecticidal potency against C. maculatus at several levels. Mortality, oviposition and rate of emergence were all affected. These results are consistent with those of Wagner et al. (2021) [7], who observed a strong toxic potency of L. dentata EO against T. castaneum and S. zeamais during 6 h exposures. With the same approach, L. angustifolia EO exhibited significant toxic potency against two types of aphid pests of the chili and bean M. persicae and A. pisum, with a mortality of 100% after exposure to 2 µL/L in air [30].

Insecticidal effects of L. dentata EO against the pests studied can be attributed to its main constituents, camphor, eucalyptol and fenchone, all of which exhibited strong potency against insects of stored cereal and legume seeds, including S. zeamais and T. castaneum [31][32]. These results are consistent with those of other studies which have found that EOs, rich in camphor and eucalyptol exhibit significant toxic potency against phytophagous [33][34]. Although the mechanism of action of lavender EO on insects has was not investigated directly in this paper, studies have reported the effect of terpenoids such as eucalyptol, and camphor, which affect the nervous system, by blocking the action of the acetylcholinesterase enzyme (AChE) of insects [30][35][36][37]. In addition, a study conducted on the action of M. arvensis EO tested by contact against adults S. granarius, reported rapid paralysis and altered walking [31][38]. During the same study, essences of M. arvensis also induced spectacular physiological changes in treated insects, marked by up-regulation of the majority of differentially expressed proteins (DEP), which are involved in development and function of the nervous and muscular systems, protein synthesis, cellular respiration, and detoxification [39]. These findings suggest that EOs can affect a wide range of biological processes, and highlight the repair mechanisms used by surviving insects to restore the harm caused.

A significant reduction in fecundity and emergence was also observed in the insect C. maculatus, which was indicative of the strong ovicidal and larvicidal activity of L. dentata EO. Indeed, the ovicidal effect of EO tested was probably caused by blockage of embryogenesis after penetration of volatile oils into eggs through the respiratory tract of C. maculatus [40][41]. This is due to the direct toxicity of these compounds, which inhibit metabolic activity of eggs. This was the case for piperitone isolated from the EO of C. schoenanthus tested on C. maculatus eggs [42] and β-asarone identified in the oil of A. calamus tested on C. chinensis, S. oryzae and S. granarius eggs [43]. Further work on another bruchid species has demonstrated that the degree of sensitivity and vulnerability of eggs to the vapours of three EOs including L. hybrida varied according to ages of eggs and stages of embryonic development [44]. Alternatively, some reports have indicated that EOs have a sterilizing effect on eggs [43].

Results of this study demonstrated total elimination of emergence when eggs were exposed to 5 μL EO/L, which could be explained by larvicidal effects of lavender EO and their major constituent linalool. This conclusion was consistent with previous results where young larvae (L1) of the cereal seed pest T. confusum were most sensitive to toxic effects of L. spica EO and linalool, with LC50 = 19.535 μL/L air and LC50 = 14.198 μL/L air, respectively during 24 h of exposure [45]. In the same study, linalool caused greater mortality of eggs than did L. spica oil at equal concentrations and reduced emergence of surviving adults, larvae and pupae [45].

Repellency of L. dentata EO was moderate at all concentrations tested. Efficacy of EO-based repellents is usually short-lived and related to their volatility. Furthermore, synthetic repellents tend to be more effective and/or persist longer than natural repellents [46]. The degree of recursiveness of EOs is mainly due to their composition. Monoterpenes such as camphor, α-pinene, thymol and cineole are frequent components of a variety of EOs mentioned in the literature as repelling mosquitoes [47][48].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/plants11030311

References

- Moumni, M.; Romanazzi, G.; Najar, B.; Pistelli, L.; Amara, H.B.; Mezrioui, K.; Karous, O.; Chaieb, I.; Allagui, M.B. Antifungal activity and chemical composition of seven essential oils to control the main seedborne fungi of cucurbits. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 104.

- Dammak, I.; Hamdi, Z.; Kammoun El Euch, S.; Zemni, H.; Mliki, A.; Hassouna, M.; Lasram, S. Evaluation of antifungal and anti-ochratoxigenic activities of Salvia officinalis, Lavandula dentata and Laurus nobilis essential oils and a major monoterpene constituent 1,8-cineole against Aspergillus carbonarius. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 128, 85–93.

- Fisher, M.C.; Hawkins, N.J.; Sanglard, D.; Gurr, S.J. Worldwide emergence of resistance to antifungal drugs challenges human health and food security. Science 2018, 360, 739–742.

- Shang, Y.; Hasan, K.; Ahammed, G.J.; Li, M.; Yin, H. Applications of Nanotechnology in Plant Growth and Crop Protection: A Review. Molecules 2019, 24, 2558.

- Allali, A.; Rezouki, S.; Louasté, B.; Bouchelta, Y.; El Kamli, T.; Eloutassi, N.; Fadli, M. Study of the nutritional quality and germination capacity of Cicer arietinum infested by Callosobruchus maculatus (Fab.). Plant Cell Biotechnol. Mol. Biol. 2020, 21, 44–56.

- Matos, L.F.; Barbosa, D.R.e.S.; da Cruz Lima, E.; de Andrade Dutra, K.; Navarro, D.M.d.A.F.; Alves, J.L.R.; Silva, G.N. Chemical composition and insecticidal effect of essential oils from Illicium verum and Eugenia caryophyllus on Callosobruchus maculatus in cowpea. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 145, 112088.

- Wagner, L.S.; Sequin, C.J.; Foti, N.; Campos-Soldini, M.P. Insecticidal, fungicidal, phytotoxic activity and chemical composition of Lavandula dentata essential oil. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 35, 102092.

- Bourhia, M.; Laasri, F.E.; Aourik, H.; Boukhris, A.; Ullah, R.; Bari, A.; Ali, S.S.; El Mzibri, M.; Benbacer, L.; Gmouh, S. Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Activities of Bioactive Compounds Contained in Rosmarinus officinalis Used in the Mediterranean Diet. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 2019, 7623830.

- Miladi, H.; Slama, R.B.; Mili, D.; Zouari, S.; Bakhrouf, A.; Ammar, E. Essential oil of Thymus vulgaris L. and Rosmarinus officinalis L.: Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis, cytotoxicity and antioxidant properties and antibacterial activities against foodborne pathogens. Nat. Sci. 2013, 5, 729–739.

- Zuzarte, M.; Vale-Silva, L.; Gonçalves, M.J.; Cavaleiro, C.; Vaz, S.; Canhoto, J.; Pinto, E.; Salgueiro, L. Antifungal activity of phenolic-rich Lavandula multifida L. Essential oil. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 31, 1359–1366.

- Bachiri, L.; Echchegadda, G.; Ibijbijen, J.; Nassiri, L. Etude Phytochimique Et Activité Antibactérienne De Deux Espèces De Lavande Autochtones Au Maroc: «Lavandula stoechas L. et Lavandula dentata L.». Eur. Sci. J. 2016, 12, 313.

- EDQM. European Pharmacopoeia, 8th ed.; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2013.

- Imelouane, B.; Elbachiri, A.; Ankit, M.; Benzeid, H.; Khedid, K. Physico-chemical compositions and antimicrobial activity of essential oil of eastern moroccan Lavandula dentata. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2009, 11, 113–118.

- Soro, k.D.; Majdouli, K.; Khabbal, Y.; Zaïr, T. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of Lavandula species L. dentata L., L. pedunculata Mill and Lavandula abrialis essential oils from Morocco against food-borne and nosocomial pathogens. Int. J. Innov. Appl. Stud. 2014, 7, 774–781.

- Bettaieb Rebey, I.; Bourgou, S.; Saidani Tounsi, M.; Fauconnier, M.-L.; Ksouri, R. Etude de la composition chimique et de l’activité antioxydante des différents extraits de la Lavande dentée (Lavandula dentata). J. New Sci. 2017, 39, 2096–2105.

- Justus, B.; de Almeida, V.P.; Gonçalves, M.M.; da Silva Fardin de Assunção, D.P.; Borsato, D.M.; Arana, A.F.M.; Maia, B.H.L.N.S.; de Fátima Padilha de Paula, J.; Budel, J.M.; Farago, P.V. Chemical composition and biological activities of the essential oil and anatomical markers of Lavandula dentata L. Cultivated in Brazil. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2018, 61, e18180111.

- Giuliani, C.; Bottoni, M.; Ascrizzi, R.; Milani, F.; Papini, A.; Flamini, G.; Fico, G. Lavandula dentata from Italy: Analysis of Trichomes and Volatiles. Chem. Biodivers. 2020, 17, e2000532.

- Cutillas, A.B.; Carrasco, A.; Martinez-Gutierrez, R.; Tomas, V.; Tudela, J. Thyme essential oils from Spain: Aromatic profile ascertained by GC–MS, and their antioxidant, anti-lipoxygenase and antimicrobial activities. J. Food Drug Anal. 2018, 26, 529–544.

- Ramzi, A. Mothana Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities and gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC/MS) analysis of the essential oils of Ajuga bracteosa Wall. ex Benth. and Lavandula dentata L. growing wild in Yemen. J. Med. Plants Res. 2012, 6, 3066–3071.

- Baptista, R.; Madureira, A.M.; Jorge, R.; Adão, R.; Duarte, A.; Duarte, N.; Lopes, M.M.; Teixeira, G. Antioxidant and antimycotic activities of two native Lavandula species from Portugal. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 1–10.

- Viuda-Martos, M.; Mohamady, M.A.; Fernández-López, J.; Abd ElRazik, K.A.; Omer, E.A.; Pérez-Alvarez, J.A.; Sendra, E. In vitro antioxidant and antibacterial activities of essentials oils obtained from Egyptian aromatic plants. Food Control 2011, 22, 1715–1722.

- De Martinoa, L.; De Feoa, V.; Fratiannib, F.; Nazzaro, F. Chemistry, Antioxidant, Antibacterial and Antifungal Activities of Volatile Oils and their Components. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2009, 4, 1741–1750.

- EL Moussaoui, A.; Bourhia, M.; Jawhari, F.Z.; Salamatullah, A.M.; Ullah, R.; Bari, A.; Mahmood, H.M.; Sohaib, M.; Serhii, B.; Rozhenko, A.; et al. Chemical Profiling, Antioxidant, and Antimicrobial Activity against Drug-Resistant Microbes of Essential Oil from Withania frutescens L. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5168.

- Astapchuk, I.; Yakuba, G.; Nasonov, A. Efficacy of fungicides against pathogens of apple core rot from the genera Fusarium Link, Alternaria Nees and Botrytis (Fr.) under laboratory conditions. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 285, 03015.

- Angioni, A.; Barra, A.; Coroneo, V.; Dessi, S.; Cabras, P. Chemical composition, seasonal variability, and antifungal activity of Lavandula stoechas L. ssp. stoechas essential oils from stem/leaves and Flowers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 4364–4370.

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, Y.H.; Ye, M.; Wang, K.B.; Fan, L.M.; Su, F.W. Chemical composition and antifungal activity of essential oil from Origanum vulgare against Botrytis cinerea. Food Chem. 2021, 365, 130506.

- Lagrouh, F.; Dakka, N.; Bakri, Y. The antifungal activity of Moroccan plants and the mechanism of action of secondary metabolites from plants. J. Mycol. Med. 2017, 27, 303–311.

- Pradebon Brondani, L.; Alves da Silva Neto, T.; Antonio Freitag, R.; Guerra Lund, R. Evaluation of anti-enzyme properties of Origanum vulgare essential oil against oral Candida albicans. J. Mycol. Med. 2018, 28, 94–100.

- McDonald, L.L.; Guy, R.H.; Speirs, R.D. Preliminary Evaluation of New Candidate Materials as Toxicants, Repellents, and Attractants against Stored-Product Insects; US Agricultural Research Service: Logan, UT, USA, 1970; pp. 1–8.

- Digilio, M.C.; Mancini, E.; Voto, E.; De Feo, V. Insecticide activity of Mediterranean essential oils. J. Plant Interact. 2008, 3, 17–23.

- Abdelgaleil, S.A.; Mohamed, M.I.; Badawy, M.E.; El-Arami, S.A. Fumigant and contact toxicities of monoterpenes to Sitophilus oryzae (L.) and Tribolium castaneum (Herbst) and their inhibitory effects on acetylcholinesterase activity. J. Chem. Ecol. 2009, 35, 518–525.

- Nukenine, E.N.; Adler, C.; Reichmuth, C. Bioactivity of fenchone and Plectranthus glandulosus oil against Prostephanus truncatus and two strains of Sitophilus zeamais. J. Appl. Entomol. 2010, 134, 132–141.

- Abdelgaleil, S.A. Molluscicidal and insecticidal potential of monoterpenes on the white garden snail, Theba pisana (Muller) and the cotton leafworm, Spodoptera littoralis (Boisduval). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2010, 45, 425–433.

- Jiang, H.; Wang, J.; Song, L.; Cao, X.; Yao, X.; Tang, F.; Yue, Y. GCxGC-TOFMS analysis of essential oils composition from leaves, twigs and seeds of cinnamomum camphora L. presl and their insecticidal and repellent activities. Molecules 2016, 21, 423.

- López, M.D.; Pascual-Villalobos, M.J. Mode of inhibition of acetylcholinesterase by monoterpenoids and implications for pest control. Ind. Crops Prod. 2010, 31, 284–288.

- Rizvi, S.A.H.; Ling, S.; Tian, F.; Xie, F.; Zeng, X. Toxicity and enzyme inhibition activities of the essential oil and dominant constituents derived from Artemisia absinthium L. against adult Asian citrus psyllid Diaphorina citri Kuwayama (Hemiptera: Psyllidae). Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 121, 468–475.

- Shahriari, M.; Zibaee, A.; Sahebzadeh, N.; Shamakhi, L. Effects of α-pinene, trans-anethole, and thymol as the essential oil constituents on antioxidant system and acetylcholine esterase of Ephestia kuehniella Zeller (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2018, 150, 40–47.

- Karima, K.-G.; Nadia, L.; Ferroudja, M.-B. Fumigant and repellent activity of Rutaceae and Lamiaceae essential oils against Acanthoscelides obtectus Say. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2016, 11, 1499–1503.

- Renoz, F.; Demeter, S.; Degand, H.; Nicolis, S.C.; Lebbe, O.; Martin, H.; Deneubourg, J.-L.; Fauconnier, M.L.; Morsomme, P.; Hance, T. The modes of action of Mentha arvensis essential oil on the granary weevil Sitophilus granarius revealed by a label-free quantitative proteomic analysis. J. Pest Sci. 2022, 95, 381–395.

- Wightman, J.A.; Southgate, B.J. Egg morphology, host, and probable regions of origin of the bruchids (coleoptera: Bruchidae) that infest stored pulses—An identification aid. N. Z. J. Exp. Agric. 1982, 10, 95–99.

- Nyamador, S.W.; Ketoh, G.K.; Koumaglo, H.K.; Glitho, I.A. Activités Ovicide et Larvicide des Huiles Essentielles de Cymbopogon giganteus Chiov. et de Cymbopogon nardus L. Rendle sur les stades immatures de Callosobruchus maculatus F. et de Callosobruschus subinnotatus Pic. (Coleoptera: Bruchidae). J. Soc. Ouest-Afr. Chim. 2010, 29, 67–79.

- Ketoh, G.K.; Koumaglo, H.K.; Glitho, I.A.; Huignard, J. Comparative effects of Cymbopogon schoenanthus essential oil and piperitone on Callosobruchus maculatus development. Fitoterapia 2006, 77, 506–510.

- Schmidt, G.H.; Risha, E.M.; El-Nahal, A.K.M. Reduction of progeny of some stored-product Coleoptera by vapours of Acorus calamus oil. J. Stored Prod. Res. 1991, 27, 121–127.

- Papachristos, D.P.; Stamopoulos, D.C. Fumigant toxicity of three essential oils on the eggs of Acanthoscelides obtectus (Say) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae). J. Stored Prod. Res. 2004, 40, 517–525.

- Kheloul, L.; Anton, S.; Gadenne, C.; Kellouche, A. Fumigant toxicity of Lavandula spica essential oil and linalool on different life stages of Tribolium confusum (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). J. Asia. Pac. Entomol. 2020, 23, 320–326.

- Fradin, M.S.; Day, J.F. Comparative Efficacy of Insect Repellents against Mosquito Bites. N. Engl. J. Med 2002, 347, 13–18.

- Jaenson, T.G.T.; Pålsson, K.; Borg-Karlson, A.K. Evaluation of extracts and oils of mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae) repellent plants from Sweden and Guinea-Bissau. J. Med. Entomol. 2006, 43, 113–119.

- Yang, P.; Ma, Y. Repellent effect of plant essential oils against Aedes albopictus. J. Vector Ecol. 2005, 30, 231–234.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!