Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Energy & Fuels

Even though electric vehicles (EV) were invented over a century ago, their popularity has grown significantly within the last 10 years due to the development of Li-ion battery technology. This evolution created an increase in the fire risk and hazards associated with this type of high-energy battery.

- li-ion battery

- electromobility

- hybrid and electric vehicles

- electric vehicle fire

1. Introduction

Hybrid and electric vehicles (EVs) rely on electric power to drive. This review is focused on passenger road vehicles that are partially or fully powered by Li-ion batteries. It also presents how the performance-based fire safety analysis could be used for underground car park safety in the case of EV fires.

EVs are becoming increasingly popular and are not only a symbol of clean transportation, but they also promise excellent technical performance [1][2]. However, compared to conventionally-fueled cars, which still maintain good sales, electric vehicles raise doubts regarding fire safety [3][4]. The doubts may be due to EV fire incidents that have happened in previous years. It was proven that most of those fire accidents were caused by the thermal runaway of Li-ion batteries, their self-ignition in parked vehicles or while driving, and fires after traffic accidents [5]. Based on the above, it could be concluded that, as a result of the increased popularity of EVs, the probability of fire incidents will also increase.

The literature shows that batteries are not only the first ignited component [6][7][8][9]. They also pose the major fuel to feed the vehicle fire, similar to gasoline or diesel fuels in conventional cars. It appears that the most relevant battery fire dynamics are battery material and its chemistry [9].

Fire is one of the many risks that impact vehicles. When considering both battery electric vehicle (BEV) and plug-in hybrid electric vehicle (PHEV) fire incidents, the risk and hazard may be found with the battery cell and power system and may be determined by the size and capacity of the battery pack [7]. It could be concluded that the greater the number of batteries installed, the greater the amount of energy will be produced, thus increasing the fire risk [10][11].

Li-ion batteries have become the most common power source for EVs, with increased concerns for passenger safety due to the increasing understanding of LIB hazard issues [12]. It depends on the scale of deployment and energy density of the battery pack. The element lithium itself has questions of safety attributed to it [13]. When a Li-ion battery is physically impacted, it can break, ejecting sparks, gases that are flammable, and toxic combustion products [14][15]. These can be further ignited and lead to burning, flames, and/or a gas explosion [16].

1.1. The Electric Vehicle Market Expansion

The EV was invented in the 19th century [1]. The first efficiently functioning electric car was created in 1882 (batteries used to power the tricycle weighed about 45 kg). It is worth adding that electric vehicles competed then with steam vehicles [17]. In the early part of the 20th century, EVs were in demand because of fuel shortages and environmental issues [2]. However, this changed when fossil fuels became cheaper [18]. Nowadays, the reduction in such fuel resources, the increasing market demand, and global warming phenomena have motivated the industry to turn back to EV solutions.

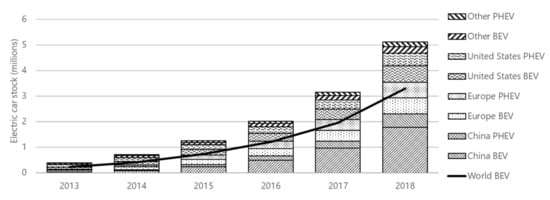

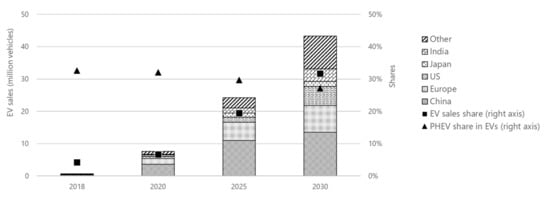

McKinsey’s Electric Vehicle Index has suggested that EV sales have been growing significantly every year since 2010 [19]. In 2018, EV ownership was in excess of 5.1 million vehicles. This was an increase of 2 million vehicles from the previous year. China is now regarded as the world’s biggest electric car market. Europe and the United States are also major purchasers. Figure 1 shows the global electric car sales and market share from 2013 to 2018. Future trends in the popularity of EVs suggest a dynamic market. EV vehicle development is strongly based on the stimulation of government policies and technological advances, as well as proactive participation of the private sector, with substantial investment in this sector (Figure 2) [20].

Figure 1. Global electric car sales and market share from 2013 to 2018 (BEVs = battery electric vehicles; PHEVs = plug-in hybrid electric vehicles) [20].

Figure 2. Global future trends of EV popularization for road EVs [20].

1.2. Performance-Based Fire Engineering

The Society of Fire Protection Engineers (SFPE) from the United States [21] defines performance-based design as an engineering approach to establish fire safety goals and objectives, to analyze fire scenarios, and to quantitatively assess design alternatives against fire safety goals and objectives. Performance-based designing uses engineering tools, methodologies, and performance criteria.

The concepts behind a performance-based approach were introduced in the 1970s. They allow greater flexibility in the design and application of fire safety and protection systems. After the 1990s, standards were introduced to provide guidance based on a performance-based approach. The key concepts were developed by BSI when, in 2001, British Standard BS 7974 [22] was published. As well as providing a framework for an engineering approach to the achievement of required fire safety in buildings, it also provided a “rational methodology for the design of buildings”. The standard was created for designing new buildings and the appraisal of existing buildings. The key benefits reached by the British Standard were that it provided:

-

The designer with a uniform approach to fire safety design;

-

The safety levels for different designs to be comparable;

-

Basis for selection of the most appropriate fire protection systems;

-

Opportunities for innovative forms of designing;

-

Background on the management methods of fire safety for a building.

The main standard is supported by several guidance documents published as “Public Documents” or PDs. These documents were designed to provide fire safety engineers with additional information to allow them to formulate effective and relevant performance-based fire strategies. Each PD, also referred to as a sub-system, covers a specific area of consideration:

-

Fire growth within the enclosure of origin;

-

Smoke and toxic gas distribution within and beyond the enclosure of origin;

-

Structural response to fire and its spread beyond the enclosure of origin;

-

Detection of fire and activation of fire protection systems;

-

Fire and rescue service intervention;

-

Occupant evacuation conditions;

-

Probabilistic risk assessment;

-

Property protection, business and mission continuity, and resilience.

2. Historical Electric and Hybrid Vehicle Fire Accidents and Lessons Learned

A review of historical electric and hybrid vehicle fire accidents shows how serious a problem this could be. The following list shows a selection of accidental EV fires from 2008 to 2019. Because the number of EV fire incidents in car parks is relatively small, the cases presented below demonstrates various types of fire events in these cars. The intention was to present in which situations an EV fire could appear. In general, similar situations could happen in a car park, and stakeholders should be aware of this risk.

-

7 June 2008: A Toyota Prius caught fire due to spontaneous ignition while in transit. This vehicle was converted to a PHEV. The main reason could be an improper assembly of bolted joints with electrical lugs inside the battery pack, which triggered the overheating and thermal runaway of the battery cell [23];

-

May 2012: A Nissan GTR crashed and caught fire. The fire was caused by electric arcs created by the short-circuiting of high voltage lines, which ignited the vehicle’s combustibles (interior materials and around 75% of the power batteries) [28];

-

29 October 2012: After Hurricane Sandy flooding, a Toyota Prius Plug-in Hybrid and 16 Fisker Karmas caught fire while being parked in a marine. The fire was caused by saltwater expansion into the electrical system, its corrosion, and finally—a short circuit in the unit [29];

-

1 October 2013: A Tesla Model S caught fire after the vehicle hit debris while being driven on a highway [32]. Flames began coming out both of the fronts at the end of the car. Extinguishing the fire with water obtained from outside of the car was unsuccessful because the fire reignited underneath the vehicle. Water given directly to the burning battery extinguished it finally [33];

-

6 November 2013: A Tesla Model S being driven in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, caught fire after it struck a tow hitch on the roadway that caused damaged beneath the vehicle [34];

-

February 2014: In Toronto, Canada, a Tesla Model S caught fire while parked in a garage, but it was not charged [35];

-

15 August 2016 in France: A Tesla Model S 90D caught fire during a promotional test drive. The vehicle started burning spontaneously and was destroyed within 5 min. Tesla suggested a “bolted electrical connection” that was “improperly tightened” under the production process, causing the fire [40][41];

-

25 August 2017 in California: Tesla Model X lost control over an embankment and struck a garage, starting a fire that completely damaged the car [42];

-

18 October 2017 in Austria: A Tesla Model S crashed on a concrete barrier at a motorway, which initiated the fire in the battery at the front of the vehicle [43]. The fire was described as extremely severe with a lot of toxic gas production;

-

7 December 2017 in Germany: A VW e-Golf caught fire in a high-voltage battery space; after initial cooling, the firefighters moved the vehicle into a water container [44];

-

January 2018: A driving Kia Optima Hybrid spontaneously caught fire, and the whole car started to burn just 30 s after it started. The causes were electrical in nature but not determined in detail. [45];

-

16 March 2018 in Thailand: A Panamera E-Hybrid burst into flames while being plugged into a household outlet for charging [46];

-

August 31, 2018: A Lifan 650 ignited and was completely lost as the fire could not be extinguished in time. The fire initiated spontaneously under the car, in the battery space. During the fire, several small explosions and significant emissions of toxic black smoke were noticed [47];

-

16 March 2018 in Thailand: A Porsche Panamera caught fire and exploded while its battery was being charged. The reason was an improper installation and working of the charging system [48];

-

8 May 2018: A Tesla Model S hit a wall, causing the battery pack to ignite. The battery reignited twice, requiring it to be extinguished three times in total [49];

-

8 February 2019 in Pennsylvania: A Tesla Model S caught on fire being parked in a garage. The same car caught on fire again two months later (on April 8th), while it was under investigation [55];

-

24 February 2019 in Canada: A Tesla Model X was completely burned in the middle of a frozen lake; during the fire, numerous small explosions were noticed, and firefighters arrived about 30 min after the fire began, which appeared to be too late [58];

-

21 April 2019 in China: A Tesla Model S caught on fire and exploded in an underground car park; in total, five cars were damaged by the fire [59];May 2019: An Outlander caught fire after immersion in saltwater [60];

-

4 May 2019: A Tesla Model S spontaneously caught on fire while not plugged in, with smoke observed near the rear right tire [61];13 May 2019: A Tesla Model S in Hong Kong caught on fire while parked [62];

-

1 June 2019 in Belgium: A Tesla Model S burned down while supercharging [63];

-

10 August 2019 in Russia: A Tesla Model 3 hit a truck on a high-speed road and subsequently burned down [64];

-

26 July 2019 in Canada: A Kona Electric caught on fire while being parked in a residential garage in Montreal. The car was not plugged in. The fire triggered an explosion and caused damage to the attached structure [66];

-

28 July 2019 in South Korea: A Kona Electric caught fire while charging [67];

-

13 August 2019 in South Korea: A Kona Electric burst into flames while being charged in an underground car park. The vehicle was completely destroyed [68];

-

1 May 2019 in Portugal: A Porsche Panamera E-Hybrid caught fire after hitting a pillar of a bridge [69];

-

16 February 2020 in Florida: A Porsche Taycan completely burned while parked in a residential garage [70].

Lessons from Historical Accidents

As detailed in the previous section, EV fires have been widely reported in recent years. Note that the total number of EV fires is much smaller than traditionally-fueled fires [3][71]. When a fire incident involves EVs, an investigation often shows that the battery was the primary cause. However, the battery fire can be attributed to many other factors, which may include charging system failures, cable overload, or arson [72][73]. The research shows that when a battery fails, it can create several different outcomes, such as venting, fire, or even internal battery explosions. Additionally, if the gas vented from the battery accumulates in a confined space of the vehicle body, it could also lead to an explosion outside of the battery box. This type of external explosion is usually not addressed by battery testing. Thus, it is less well recognized than internal battery explosions [74]. EV fire scenarios are still being updated. Instances can be categorized as one or more of the following:

-

The EV catches fire while stationary (self-ignition). This may be caused by extreme weather conditions (low/high temperatures and high humidity, saltwater destruction) or internal cell failure.

-

The EV catches fire while being charged. This failure may be due to battery failure due to overcharging and/or faulty or insecure charging stations and/or cables.

-

The EV catches fire as a result of a collision or other types of damage.

-

EV batteries are also a subject of thermal abuse and reignition after fire extinguishment [75].

3. Controls on EV Production and Approvals

EV batteries, before they can be sold, are required to pass standard tests (e.g., in accordance with ISO 12405-3, ISO 6469-1, UN 38.3, UN R100, SAE J2464, SAE J2929, IEC 62133, IEC 626602, IEC 62660-3, GB/T 31485). Requirements differ between countries [76][77], but generally, all EV batteries must pass safety tests that evaluate their failure response [78]. Another goal is set by battery fire tests. In this case, fire growth and development are observed to determine possible consequences in a real fire accident.

3.1. Standard Tests for EV Batteries

As highlighted above, the most common battery failure mode is a thermal runaway, which could be triggered after mechanical, thermal, and electrical damage. In such cases, the battery voltage drops because of damage to battery electrodes. Its temperature rises above the heat dissipation rate. The pressure increases because of the reaction among active battery materials, their organic electrolyte evaporation, and flammable gas generation, leading to an accumulation of gases in the battery [79]. The main parameters that are measured during the tests are voltage, current, and temperature [80]. The European Council for Automotive Research and Development (EUCAR) provides a classification system (Table 1).

Table 1. EUCAR Hazard Severity Levels [81].

| Hazard Level | Description | Classification Criteria and Effect |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | No effect | No effect. No loss of functionality |

| 1 | Passive protection activated | No physical damage nor fire hazard. |

| 2 | Defect/damage | No fire hazard, but physical cell damage noticed. |

| 3 | Leakage—mass loss < 50% | No fire hazard but electrolyte weight loss < 50% |

| 4 | Venting—mass loss ≥ 50% | No fire hazard but electrolyte weight loss ≥ 50% |

| 5 | Fire or flame | Fire hazard but no rupture or explosion (no flying parts) |

| 6 | Rupture | Fire hazard with flying parts but no explosion |

| 7 | Explosion | Fire hazard with flying parts and explosion (i.e., disintegration of the cell) |

3.2. Real Scale Tests for EV Batteries

Unfortunately, research into large-scale EV battery testing is still inconclusive. The literature warns against misinterpretation of the data of small-scale battery fires in an attempt to evaluate the hazards of large-scale EV fires [75][82][83].

For fire engineering evaluation purposes, the heat release rate (HRR) or the total heat release from fire is the standard measurement of fire size and is the most important parameter of the EV fire hazard assessment [84], for use when assessing car park fire safety system designs [85][86][87][88]. The HRR can be taken as:

where ṁ is the burning rate [kg/s] determined by the mass-loss rate from testing [89]; ΔHe is the heat of combustion [MJ/kg]; Af is the floor/surface area of fuel or fire [m2], which is the floor of the EV; ṁ″ is the burning flux [kg/m2-s]; ŋ is the combustion efficiency, which depends on the oxygen supply; and ΔHc is the heat of combustion for EV batteries, which varies with the type and SOC of LIB.

HRR = ṁΔHe =Afṁ″ŋΔHc

The exact EV battery fire size is not conclusive. For example, the Tesla Model S battery of 2250 kg is five times greater than that of a battery cell (45 g for a 18,650 cell), and the HRR of fire is increased three times. The HRR can range from several kW for a battery cell [10] to several hundred kW for a single EV battery pack [82] and several MWs for a full-scale EV fire [75][83].

The energy of an EV fire can also be assessed by using the average heat flux (q″) of the battery pack and its area. For the calculation, the SOC can be taken as 100%, which represents the worst-case fire scenario [90]. Using the example of an EV powered by Lithium Titanate (LTO) batteries, the average heat flux (q″) is approximately 2.3 MW/m2 in a fully charged stage [91]. Considering the floor area of the battery AEV ≈ 3 m2, the average fire HRR of this kind of EV can be estimated as 7 MW (1).

HRR = AEV q″= 3 m2 × 2.3 MW/m2 ≈ 7 MW

This calculated HRR could also be used to evaluate the necessary amount of water or other fire-suppression agents to extinguish the EV fire.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/en15020649

References

- Matulka, R. The History of the Electric Car. Department of Energy. 2014. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/articles/history-electric-car (accessed on 20 October 2018).

- Anderson, C.D.; Anderson, J. Electric and Hybrid Cars, 2nd ed.; McFarland &Company: Jefferson, NC, USA, 2010.

- Boehmer, H.; Klassen, M.; Olenick, S. Modern Vehicle Hazards in Parking Structures and Vehicle Carriers. 2020. Available online: https://www.nfpa.org/News-and-Research/Data-research-and-tools/Building-and-Life-Safety/Modern-Vehicle-Hazards-in-Parking-Garages-Vehicle-Carriers (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Bisschop, R.; Willstrand, O.; Rosengren, M. Handling lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles—preventing and recovering from hazardous events. In Proceedings of the 1st International Symposium on Lithium Battery Fire Safety, Hefei, China, 18–20 July 2019.

- National Transportation Safety Board. Preliminary Report: Crash and Post-Crash Fire of Electric-Powered Passenger Vehicle; National Transportation Safety Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Wang, Q.; Ping, P.; Zhao, X.; Chu, G.; Sun, J.; Chen, C. Thermal runaway caused fire and explosion of lithium ion battery. J. Power Sources 2012, 208, 210–224.

- Wang, Q.; Mao, B.; Stoliarov, S.I.; Sun, J. A review of lithium ion battery failure mechanisms and fire prevention strategies. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2019, 73, 95–131.

- Feng, X.; Ouyang, M.; Liu, X.; Lu, L.; Xia, Y.; He, X. Thermal runaway mechanism of lithium ion battery for electric vehicles: A review. Energy Storage Mater. 2018, 10, 246–267.

- Ouyang, D.; Chen, M.; Huang, Q.; Weng, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J. A review on the thermal hazards of the lithium-ion battery and the corresponding countermeasures. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2483.

- Liu, X.; Wu, Z.; Stoliarov, S.I.; Denlinger, M.; Masias, A.; Snyder, K. Heat release during thermally-induced failure of a lithium ion battery: Impact of cathode composition. Fire Saf. J. 2016, 85, 10–22.

- Liu, X.; Stoliarov, S.I.; Denlinger, M.; Masias, A.; Snyder, K. Comprehensive calorimetry of the thermally-induced failure of a lithium ion battery. J. Power Sources 2015, 280, 516–525.

- Balakrishnan, P.G.; Ramesh, R.; Prem Kumar, T. Safety mechanisms in lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2006, 155, 401–414.

- Tobishima, S.I.; Yamaki, J.I. A consideration of lithium cell safety. J. Power Sources 1999, 81–82, 882–886.

- Evarts, E.C. Lithium batteries: To the limits of lithium. Nature 2015, 526, S93–S95.

- Lecocq, A.; Eshetu, G.G.; Grugeon, S.; Martin, N.; Laruelle, S.; Marlair, G. Scenario-based prediction of Li-ion batteries fire-induced toxicity. J. Power Sources 2016, 316, 197–206.

- Gough, N. Sony Warns Some New Laptop Batteries May Catch Fire. The New York Times, 12 April 2014. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/12/technology/sony-warns-some-new-laptop-batteries-may-catch-fire.html(accessed on 20 March 2019).

- Business Insider Polska. Available online: https://businessinsider.com.pl/motoryzacja/pierwszy-samochod-elektryczny-na-swiecie-historia-motoryzacji/2jxm5w0 (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Grauers, A.; Sarasini, S.; Karlstrom, M.; Industriteknik, C. Why electromobility and what is it? In Systems Perspectives on Electromobility; Sande’n, B., Ed.; Chalmers University of Technology: Goteborg, Sweden, 2013.

- Hertzke, P.; Müller, N.; Schenk, S.; Wu, T. The Global Electric-Vehicle Market Is Amped up and on the Rise; McKinsey Center for Future Mobility, McKinsey & Company: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018.

- Global EV Outlook. Scaling-Up the Transition to Electric Mobility; Energy Technology Policy (ETP) Division of the Directorate of Sustainability, Technology and Outlooks (STO), International Energy Agency: London, UK, 2019.

- SFPE Website. Society of Fire Protection Engineers. Available online: https://www.sfpe.org/page/about (accessed on 11 August 2020).

- BS 7974:2019Application of Fire Safety Engineering Principles to the Design of Buildings. Code of Practice, British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2019.

- Beauregard, G.P.; Phoenix, A.Z. Report of Investigation: Hybrids Plus Plug in Hybrid Electric Vehicle; National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, Inc.: Phoenix, AZ, USA; US Department of Energy, Idaho National Laboratory by ETEC: Arlington, TX, USA, 2008.

- Jensen, C. Chevy Volt Fire Prompts Federal Investigation Into Lithium-Ion Batteries. The New York Times, 11 November 2011.

- Green, J.; Welch, D.; Keane, A.G. GM Volt Fire Prompts Probe of Lithium Batteries. Bloomberg, 11 November 2011.

- Blanco, S. Second Tesla Model S fire caught on video after Mexico crash. Autoblog Green, 9 November 2013.

- Hyde, J. Second Tesla Model S fire sparked by crash in Mexico. Yahoo Autos, 9 November 2013.

- Investigation concludes fire in BYD e6 collision caused by electric arcs from short circuit igniting interior materials and part of power battery. Green Car Congress, 13 August 2012.

- Voelcker, J. Sandy Flood Fire Followup: Fisker Karma Battery Not At Fault. Green Car Reports, 7 November 2012.

- Tabuchi, H. New Problem for Boeing 787 Battery Maker. The New York Times, 13 April 2013.

- Mitsubishi Motors Press Release. Mitsubishi reports fire in i-MiEV battery pack, melting in Outlander PHEV pack. Green Car Congress, 13 April 2013.

- Jensen, C. Tesla Says Car Fire Started in Battery. The New York Times, 5 October 2013.

- Vlasic, B. Car Fire a Test for High-Flying Tesla. The New York Times, 5 October 2013.

- Ohnsman, A.; Keane, A.G. Tesla’s Third Model S Fire Brings Call for, U.S. Inquiry. Bloomberg, 8 November 2013.

- Lopez, L. Another Tesla Caught on Fire While Sitting in a Toronto Garage This Month. Business Insider, 16 February 2014.

- Nygaard, K. Tesla tok fyr og brant helt ut . Fædrelandsvennen, 1 January 2016. (In Norwegian)

- Nygaard, K. Tesla antente under lading og brant opp . Aftenposten, 1 January 2016. (In Norwegian)

- Hattrem, H.; Larsen-Vonstett, Ø. Tesla-brannen: Kortslutning i bilen, men vetikke hvorfor . VG, 18 March 2016. (In Norwegian)

- Herron, D. Model S Catches Fire in Norway at Supercharger, Charging System Seemingly at Fault, The Long Tail Pipe. Available online: https://longtailpipe.com/2016/01/01/model-s-catches-fire-in-norway-at-supercharger-charging-system-seemingly-at-fault/ (accessed on 18 March 2019).

- Lambert, F. Tesla says Model S fire in France was due to ’electrical connection improperly tightened’ by a human instead of robots. Electrek, 20 June 2018.

- Thompson, C. A Tesla Model S burst into flames during a test drive in France. Businessinsider, 20 June 2018.

- Mendoza, A. Tesla slams into Lake Forest garage, severely damaging it and sparking a fire. Orange County Register, 8 June 2018.

- Lambert, F. Tesla Model S fire vs 35 firefighters—Watch impressive operation after a high-speed crash. Electrek, 18 October 2017. Available online: https://electrek.co/2017/10/18/tesla-model-s-fire-high-speed-crash-video-impressive-operation/(accessed on 20 March 2019).

- Feuerwehr löscht brennenden E-Golf . Wolfsburger Allgemeine Zeitung , 21 June 2018. (In German)

- Chatman, S. Denton woman says Kia Won’t Reimburse Her after Car Catches Fire. NBC 5 Dallas-Fort Worth. 2018. Available online: https://www.nbcdfw.com/news/local/Denton-Woman-Says-Kia-Wont-Reimburse-Her-After-Car-Catches-Fire–491908751.html (accessed on 20 March 2019).

- Bangkok Post. Porsche catches fire while charging. 2018. Available online: https://www.bangkokpost.com/news/general/1429518/porsche-catches-fire-while-charging (accessed on 18 March 2018).

- EV Century. Lifan 650EV Spontaneously Ignited. GaoGong EV Web. 2018. Available online: http://www.gg-ev.com/asdisp2-65b095fb-26641-.html (accessed on 20 March 2019).

- Bt10m Porsche Up in Flames as Battery Charging Goes Wrong. THE NATION, 16 March 2018. Available online: https://www.nationthailand.com/news/30341102(accessed on 20 March 2019).

- Gastelu, G. NTSB: Tesla was going 116 mph at time of fatal Florida accident, battery pack reignited twice afterwards. Foxnews, 27 June 2018.

- Radiotelevisione Svizzera. Rogo A2, batterie in causa. 2018. Available online: https://www.rsi.ch/news/ticino-e-grigioni-e-insubria/Rogo-A2-batterie-in-causa-10469564.html (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Neue Zurcher Zeitung. Akku ist die mögliche Ursache für Brand bei einem tödlichen Tesla-Unfall im Tessin. 2018. Available online: https://www.nzz.ch/panorama/tesla-unfall-im-tessin-akku-als-moegliche-brandursache-ld.1385766 (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Huffman, M. Tesla investigating Model S fire in Los Angeles. Consumeraffairs, 20 June 2018.

- Beene, R. Tesla car fire examination to be observed by authorities in U.S. Europe.Autonews, 20 June 2018.

- 2 Federal Agencies Take Closer Look Into Tesla Fire In West Hollywood. Losangeles.cbslocal, 20 June 2018.

- Lambert, F. Tesla car caught on fire while being investigated for another fire. Electrek, 3 June 2018.

- Tribune Publishing. Tesla Crash Story. 2019. Available online: https://www.sun-sentinel.com/local/broward/davie/fl-ne-davie-tesla-crash-fole-20190225-story.html (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Fox News. Tesla Accident in Florida. 2019. Available online: https://www.foxnews.com/auto/driver-killed-in-fiery-tesla-accident-in-florida-after-crashing-into-trees (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Burlington Free Press. Tesla Model X burned on frozen Lake Champlain: What happened and what’s coming next. 2019. Available online: https://www.burlingtonfreepress.com/story/news/local/2019/03/01/tesla-model-x-burned-lake-champlain-what-next-steps-fire/3026364002/ (accessed on 11 December 2019).

- cnBeta. Exposure of Shanghai Tesla after Spontaneous Combustion: Audi was Burned to Scrap Metal Next to it—Tesla Electric Vehicle. cnBeta, 22 April 2019. (In Chinese)

- Caught on camera: Electric SUV plunges into water at Port Moody boat launch. CTV News, 16 May 2019.

- San Francisco Fire Department Media. Tesla S Fire. 2019. Available online: https://twitter.com/SFFDPIO/status/1124316 (accessed on 16 May 2019).

- Reuters Staff. Tesla car catches fire in Hong Kong parking lot: Media. Reuters, 3 June 2019.

- Lambert, F. Tesla vehicle caught on fire while plugged in at Supercharger station. Electrek, 2 June 2019.

- 4 PDA. Опубликованы подробности возгорания электрокара Tesla в Москве. 2019. Available online: https://4pda.ru/2019/08/12/360223/ (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- Barmash, J. Shocking moment a Tesla bursts into flames while charging. Intercontinental News, 22 November 2019.

- Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 2019. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/electric-car-catches-fire-and-explodes-in-le-bizard-garage-1.5227665 (accessed on 27 July 2019).

- Dae-sun, H. All Fires in Electric Vehicles in S. Korea This Year Involved Hyundai’s Kona Electric. 2019. Available online: http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_business/912588.html (accessed on 27 July 2019).

- Hankyoreh. A Next Car Fire. 2019. Available online: http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/ (accessed on 14 August 2019).

- JN. Porsche embate em ponte móvel de Matosinhos e faz dois mortos e quatro feridos. 2019. Available online: https://www.jn.pt/local/noticias/porto/matosinhos/dois-mortos-e-quatro-feridos-apos-carro-embater-em-ponte-movel-em-leca-10851084.html (accessed on 1 May 2019).

- CNBC. Electric Porsche Taycan Catches Fire While Parked Overnight in Garage, Company Confirms. 2020. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2020/02/18/electric-porsche-taycan-catches-fire-in-garage-company-confirms.html (accessed on 18 February 2020).

- Tesla. Tesla Vehicle Safety Report. Available online: https://www.tesla.com/VehicleSafetyReport (accessed on 20 March 2019).

- The Home Office, Road Vehicle Fires Dataset, UK, August 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/fire-statistics-incident-level-datasets (accessed on 20 March 2019).

- Huang, X.; Nakamura, Y. A review of fundamental combustion phenomena in wire fires. Fire Technol. 2020, 56, 315–360.

- Bisschop, R.; Willstrand, O.; Amon, F.; Rosengren, M. Fire Safety of Lithium-Ion Batteries in Road Vehicles; Safety & Transport Fire Research; RISE Report 2019/50; Research Institutes of Sweden: Borås, Sweden, 2019.

- Sun, P.; Huang, X.; Bisschop, R.; Niu, H. A Review of Battery Fires in Electric Vehicles. Fire Technol. 2020, 56, 1361–1410.

- Garche, J.; Brandt, K. Li-Battery Safety; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019.

- Tidblad, A.A. Regulatory outlook on electric vehicle safety. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Fires in Vehicles, Boras, Sweden, 3–4 October 2018.

- Cabrera Castillo, E. Advances in Battery Technologies for Electric Vehicles; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015.

- Kong, L.; Li, C.; Jiang, J.; Pecht, M.G. Li-Ion Battery Fire Hazards and Safety Strategies. Energies 2018, 11, 2191.

- IEC. Secondary Lithium-Ion Cells for the Propulsion of Electric Road Vehicles—Part 2: Reliability and Abuse Testing; International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- SAEJ2464:2Electric and Hybrid Electric Vehicle Rechargeable Energy Storages, SAE: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2011.

- Colella, F. Understanding electric vehicle fires. In Proceedings of the Fire Protection and Safety in Tunnels, Stavanger, Norway, 29 August–1 September 2016.

- Macneil, D.D.; Lougheed, G.; Lam, C.; Carbonneau, G.; Kroeker, R.; Edwards, D.; Tompkins, J.; Lalime, G. Electric vehicle fire testing. In Proceedings of the 8thEVS-GTR Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 1–5 June 2015.

- Drysdale, D. An Introduction to Fire Dynamics, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2011.

- Brzezinska, D.; Markowski, A. Experimental Investigation and CFD Modelling of the Internal Car Park Environment in Case of Accidental LPG Release. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2017, 110, 5–14.

- Brzezińska, D. Ventilation System Influence on Hydrogen Explosion Hazards in Industrial Lead-Acid Battery Rooms. Energies 2018, 11, 2086.

- Brzezinska, D. LPG Cars in a Car Park Environment—How to Make It Safe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1062.

- Brzezinska, D.; Dziubinski, M.; Markowski, A.S. Analyses of LPG Dispersion during Its Accidental Release in Enclosed Car Parks. Ecol. Chem. Eng. S 2017, 24, 249–261.

- Lecocq, A.; Bertana, M.; Truchot, B.; Marlair, G. Comparison of the fire consequences of an electric vehicle and an internal combustion engine vehicle. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Fires in Vehicles—FIVE 2012, Chicago, IL, USA, 27–28 September 2012; pp. 183–194.

- US Department of Transportation. Interim Guidance for Electric and Hybrid Electric Vehicles Equipped with High-Voltage Batteries; US Department of Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- Wang, Q. Study on fire and fire spread characteristics of lithium ion batteries. In Proceedings of the 2018 China National Symposium on Combustion, Harbin, China, 13–16 September 2018.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!