Integral membrane proteins from the ancient SPFH (stomatin, prohibitin, flotillin, HflK/HflC) protein superfamily are found in nearly all living organisms. Mammalian SPFH proteins are primarily associated with mitochondrial functions but also coordinate key processes such as ion transport, signaling, and mechanosensation. In addition, SPFH proteins are required for virulence in parasites.

- SPFH

- prohibitin

- stomatin

- mitochondria

- fungi

1. Introduction

The SPFH protein family is present in all domains of life. Proteins of this family are characterized by a conserved SPFH domain and diverge highly at their N- and C-terminal regions [1][2][3][4]. Furthermore, the distribution of SPFH proteins across species varies [1][2][4]. Proteomic and cellular analyses identified SPFH proteins in various cellular membranes, such as the inner mitochondrial membrane and plasma membrane [5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12]. SPFH proteins also localize to the endoplasmic reticulum and lysosome/vacuole [5][13][14]. SPFH protein overproduction in mammals, nematodes, yeast, and mice causes a broad array of phenotypes, including drug resistance, aging, apoptosis, and tumorigenesis [15][16][17]. Biochemical events dependent on SPFH proteins include palmitoylation and oligomerization and have supported a hypothesis that SPFH proteins are membrane scaffolds [18]. In vitro biochemical results showed that human stomatin protein binds directly to cholesterol and actin mainly through key amino acid sequences in the C-terminus [19]. Moreover, sequences in the SPFH domain are required for SPFH protein homo-oligomerization [19][20]. However, the details underlying the molecular function of SPFH proteins are limited.

2. SPFH Protein Function in Non-Pathogenic Fungi

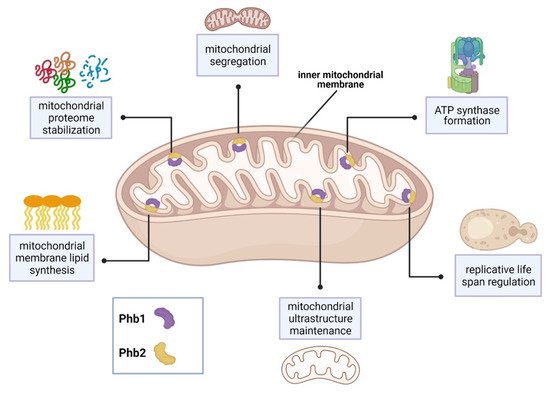

In the baker’s yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the sole SPFH proteins, prohibitin 1 and prohibitin 2 (Phb1, Phb2), form ring-shaped complexes within the inner mitochondrial membrane and are associated with several mitochondrial functions [9]. Phb1 and Phb2 interact with Mdm33 to regulate mitochondrial ultrastructure and shape [21]. In addition, Phb1 and Phb2 interact with the chaperones Atp10 and Atp23 to assist formation of F1F0-ATP synthase [22]. Depletion of prohibitins reduces yeast life span and is characterized by abnormal mitochondrial structure and delayed mitochondrial segregation to budding daughter cells [23][24][25].

Synthetic genetic arrays using a phb1Δ mutant strain identified 35 genes that are required for viability or normal growth [23]. Interestingly, 31 of these genes encode mitochondrial proteins. 19 of these genes were associated with respiratory chain assembly and maintenance of mitochondrial structure. Major PHB1 genetic partners include YTA10, YTA11, and YME1 [23]. These genes encode proteins which belong to the conserved, ATP-dependent mitochondrial m-AAA protease family, which maintain the mitochondrial proteome [26]. Other PHB1 genetic partners include the cytochrome c complex subunit-encoding genes, COX6 and COX24 [23]. In addition, 8 genes are required for the synthesis of the mitochondrial membrane lipids, cardiolipin and phosphatidylethanolamine. These partners include the highly conserved genes, UPS1 and UPS2 [23]. Lastly, prohibitin function and localization was associated with the presence of the yeast [PSI+] prion. Proteomic analysis revealed that aberrant mitochondrial function observed in [PSI+] prion yeast strains was caused, in part, by Phb1 mislocalization in the cytoplasm [27]. See Figure 1 for a summary of SPFH function in S. cerevisiae.

SPFH function has also been characterized in other non-pathogenic fungi. In the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Phb1 and Phb2 localize to the mitochondria [28]. Overexpression or deletion of the phb2 gene caused resistance to various antifungal drugs including terbinafine, fluconazole, amphotericin B, and clotrimazole [28]. Moreover, increased production of intracellular nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species were observed in Phb2 overexpression or deletion strains [28]. In contrast, only a Δphb1 deletion strain was resistant to antifungal drugs [28]. Additional genetic evidence showed that mitochondrial dysfunction caused by phb2 deletion and overexpression activated the oxidative stress response transcriptional regulator, Pap1, thus linking prohibitins to stress response signaling [28]. Paradoxically, S. cerevisiae phb2Δ mutants were sensitive to fluconazole, amphotericin B, and clotrimazole, highlighting the differences of SPFH protein function in different yeast species [28]. However, the basis of this phenotype is unknown.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS ) analyses on mitochondrial extracts identified three SPFH proteins (Phb1, Phb2 and Slp2) in the filamentous fungus, Neurospora crassa [29]. Consistent with the structural dynamics of prohibitins from mammals, nematodes, and yeast, N. crassa Phb1 and Phb2 localized to the inner mitochondrial membrane and formed large membrane complexes of various sizes. Notably, one high molecular weight prohibitin complex co-migrated with m-AAA protease MAP-1. This suggests that m-AAA proteins may physically interact with prohibitins in N. crassa, similar to observations with S. cerevisiae prohibitins [29]. Moreover, the stomatin, Slp2, was found to co-migrate in a high molecular weight complex with the N. crassa i -MMM protease homolog, IAP-1, suggesting that Slp2 and IAP-1 physically interact in the inner mitochondrial membrane [29]. Taken together, these findings demonstrate the importance of SPFH protein function in mitochondrial ultrastructure, respiratory function, and antifungal drug resistance.

3. SPFH Protein Function in Pathogenic Fungi

In fungal pathogens, mitochondria are required for virulence determinants including morphogenesis, drug susceptibility, cell wall biogenesis, and biofilm formation [30][31][32]. The knowledge underlying the molecular and cellular aspects of mitochondrial function in human pathogenic fungi is based primarily on studies in the opportunistic pathogen, Candida albicans. Mitochondrial function is critical for C. albicans commensalism and virulence [30]. Indeed, C. albicans cells treated with respiratory inhibitors display aberrant cell wall structure and increased macrophage recognition [33]. Moreover, mutations to fungal-specific mitochondrial genes, such as GOA1, NUO3, NUO4, and GEM1, attenuate virulence [34][35][36][37]. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling revealed that genes encoding proteins with mitochondrial functions are significantly upregulated following cell wall damage or osmotic stress [38][39][40].

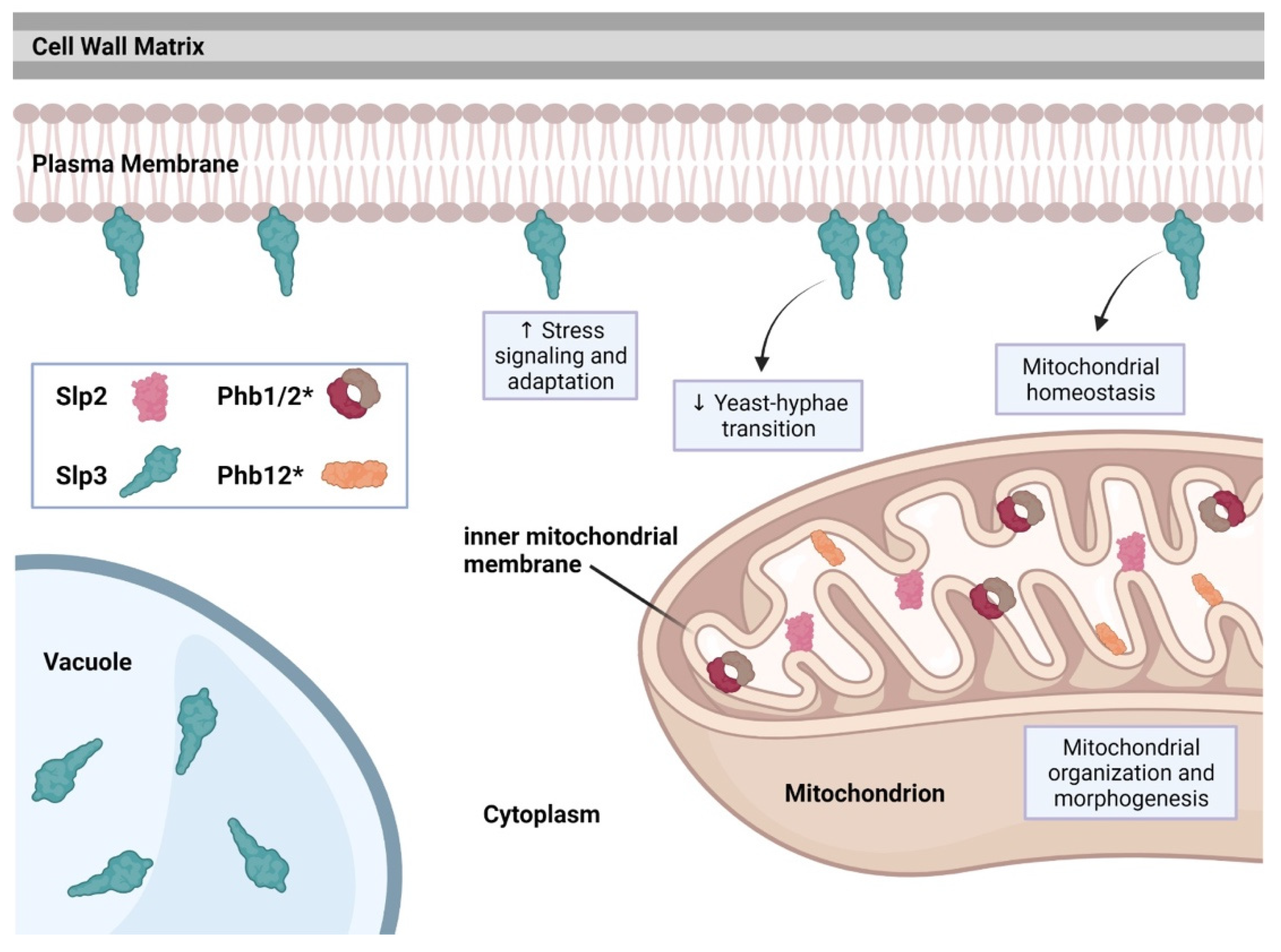

The C. albicans genome includes five SPFH family members: PHB1, PHB2, PHB12, SLP2, and SLP3 (stomatin-like protein 3) [41]. Recent studies have shown that SLP3 transcription and protein localization significantly increases following treatment with oxidative, osmotic, cell wall, or plasma membrane stress agents, categorizing SLP3 as a general stress response gene [5][39][40]. Fluorescence imaging revealed that Slp3p forms visible puncta along the plasma membrane similar to mammalian stomatin complexes [5][42]. Slp3 plasma membrane localization was also confirmed via liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and MALDI-TOF analysis on C. albicans plasma membrane extracts [6]. Deletion of Slp3p has no effect on growth under nutrient-rich conditions, environmental stress conditions, or antifungal drug treatment [5]. Moreover, the absence of Slp3p does not result in any apparent cell structure abnormality, organelle malfunction, or ion transport defects [5]. Overexpression of Slp3, however, does result in hypersensitivity to reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial depolarization specifically in yeast-phase cells [5].

C. albicans Slp2, Phb1, Phb2, and Phb12 each contain a putative mitochondrial localization signal motif (our preliminary findings). We observed Slp2 mitochondrial localization (our preliminary findings), suggesting that the mitochondrial functions for prohibitins and Slp2 may be conserved. See Figure 2 for a summary of C. albicans SPFH protein function.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/microorganisms9112287

References

- Lapatsina, L.; Brand, J.; Poole, K.; Daumke, O.; Lewin, G.R. Stomatin-domain proteins. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 91, 240–245.

- Browman, D.T.; Hoegg, M.B.; Robbins, S.M. The SPFH domain-containing proteins: More than lipid raft markers. Trends Cell Biol. 2007, 17, 394–402.

- Rivera-Milla, E.; Stuermer, C.A.; Malaga-Trillo, E. Ancient origin of reggie (flotillin), reggie-like, and other lipid-raft proteins: Convergent evolution of the SPFH domain. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2006, 63, 343–357.

- Hinderhofer, M.; Walker, C.A.; Friemel, A.; Stuermer, C.A.; Moller, H.M.; Reuter, A. Evolution of prokaryotic SPFH proteins. BMC Evol. Biol. 2009, 9, 10.

- Conrad, K.A.; Rodriguez, R.; Salcedo, E.C.; Rauceo, J.M. The Candida albicans stress response gene Stomatin-Like Protein 3 is implicated in ROS-induced apoptotic-like death of yeast phase cells. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192250.

- Cabezon, V.; Llama-Palacios, A.; Nombela, C.; Monteoliva, L.; Gil, C. Analysis of Candida albicans plasma membrane proteome. Proteomics 2009, 9, 4770–4786.

- Snyers, L.; Umlauf, E.; Prohaska, R. Oligomeric nature of the integral membrane protein stomatin. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 17221–17226.

- Hiebl-Dirschmied, C.M.; Adolf, G.R.; Prohaska, R. Isolation and partial characterization of the human erythrocyte band 7 integral membrane protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1991, 1065, 195–202.

- Tatsuta, T.; Model, K.; Langer, T. Formation of membrane-bound ring complexes by prohibitins in mitochondria. Mol. Biol. Cell 2005, 16, 248–259.

- Da Cruz, S.; Parone, P.A.; Gonzalo, P.; Bienvenut, W.V.; Tondera, D.; Jourdain, A.; Quadroni, M.; Martinou, J.C. SLP-2 interacts with prohibitins in the mitochondrial inner membrane and contributes to their stability. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1783, 904–911.

- Christie, D.A.; Kirchhof, M.G.; Vardhana, S.; Dustin, M.L.; Madrenas, J. Mitochondrial and plasma membrane pools of stomatin-like protein 2 coalesce at the immunological synapse during T cell activation. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37144.

- Dempwolff, F.; Schmidt, F.K.; Hervas, A.B.; Stroh, A.; Rosch, T.C.; Riese, C.N.; Dersch, S.; Heimerl, T.; Lucena, D.; Hulsbusch, N.; et al. Super Resolution Fluorescence Microscopy and Tracking of Bacterial Flotillin (Reggie) Paralogs Provide Evidence for Defined-Sized Protein Microdomains within the Bacterial Membrane but Absence of Clusters Containing Detergent-Resistant Proteins. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006116.

- Reuter, A.T.; Stuermer, C.A.; Plattner, H. Identification, localization, and functional implications of the microdomain-forming stomatin family in the ciliated protozoan Paramecium tetraurelia. Eukaryot. Cell 2013, 12, 529–544.

- Mairhofer, M.; Steiner, M.; Salzer, U.; Prohaska, R. Stomatin-like protein-1 interacts with stomatin and is targeted to late endosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 29218–29229.

- Bartolome, A.; Boskovic, S.; Paunovic, I.; Bozic, V.; Cvejic, D. Stomatin-like protein 2 overexpression in papillary thyroid carcinoma is significantly associated with high-risk clinicopathological parameters and BRAFV600E mutation. APMIS 2016, 124, 271–277.

- Signorile, A.; Sgaramella, G.; Bellomo, F.; De Rasmo, D. Prohibitins: A Critical Role in Mitochondrial Functions and Implication in Diseases. Cells 2019, 8, 71.

- Chen, T.W.; Liu, H.W.; Liou, Y.J.; Lee, J.H.; Lin, C.H. Over-expression of stomatin causes syncytium formation in nonfusogenic JEG-3 choriocarcinoma placental cells. Cell Biol. Int. 2016, 40, 926–933.

- Wai, T.; Saita, S.; Nolte, H.; Muller, S.; Konig, T.; Richter-Dennerlein, R.; Sprenger, H.G.; Madrenas, J.; Muhlmeister, M.; Brandt, U.; et al. The membrane scaffold SLP2 anchors a proteolytic hub in mitochondria containing PARL and the i-AAA protease YME1L. EMBO Rep. 2016, 17, 1844–1856.

- Rungaldier, S.; Umlauf, E.; Mairhofer, M.; Salzer, U.; Thiele, C.; Prohaska, R. Structure-function analysis of human stomatin: A mutation study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178646.

- Yokoyama, H.; Matsui, I. Crystal structure of the stomatin operon partner protein from Pyrococcus horikoshii indicates the formation of a multimeric assembly. FEBS Open Bio 2014, 4, 804–812.

- Klecker, T.; Wemmer, M.; Haag, M.; Weig, A.; Bockler, S.; Langer, T.; Nunnari, J.; Westermann, B. Interaction of MDM33 with mitochondrial inner membrane homeostasis pathways in yeast. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 18344.

- Osman, C.; Wilmes, C.; Tatsuta, T.; Langer, T. Prohibitins interact genetically with Atp23, a novel processing peptidase and chaperone for the F1Fo-ATP synthase. Mol. Biol. Cell 2007, 18, 627–635.

- Osman, C.; Haag, M.; Potting, C.; Rodenfels, J.; Dip, P.V.; Wieland, F.T.; Brugger, B.; Westermann, B.; Langer, T. The genetic interactome of prohibitins: Coordinated control of cardiolipin and phosphatidylethanolamine by conserved regulators in mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 184, 583–596.

- Kirchman, P.A.; Miceli, M.V.; West, R.L.; Jiang, J.C.; Kim, S.; Jazwinski, S.M. Prohibitins and Ras2 protein cooperate in the maintenance of mitochondrial function during yeast aging. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2003, 50, 1039–1056.

- Piper, P.W.; Jones, G.W.; Bringloe, D.; Harris, N.; MacLean, M.; Mollapour, M. The shortened replicative life span of prohibitin mutants of yeast appears to be due to defective mitochondrial segregation in old mother cells. Aging Cell 2002, 1, 149–157.

- Glynn, S.E. Multifunctional Mitochondrial AAA Proteases. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2017, 4, 34.

- Sikora, J.; Towpik, J.; Graczyk, D.; Kistowski, M.; Rubel, T.; Poznanski, J.; Langridge, J.; Hughes, C.; Dadlez, M.; Boguta, M. Yeast prion lowers the levels of mitochondrial prohibitins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1793, 1703–1709.

- Liu, Q.; Yao, F.; Jiang, G.; Xu, M.; Chen, S.; Zhou, L.; Sakamoto, N.; Kuno, T.; Fang, Y. Dysfunction of Prohibitin 2 Results in Reduced Susceptibility to Multiple Antifungal Drugs via Activation of the Oxidative Stress-Responsive Transcription Factor Pap1 in Fission Yeast. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e00860-18.

- Marques, I.; Dencher, N.A.; Videira, A.; Krause, F. Supramolecular organization of the respiratory chain in Neurospora crassa mitochondria. Eukaryot. Cell 2007, 6, 2391–2405.

- Calderone, R.; Li, D.; Traven, A. System-level impact of mitochondria on fungal virulence: To metabolism and beyond. FEMS Yeast Res. 2015, 15, fov027.

- Mamouei, Z.; Singh, S.; Lemire, B.; Gu, Y.; Alqarihi, A.; Nabeela, S.; Li, D.; Ibrahim, A.; Uppuluri, P. An evolutionarily diverged mitochondrial protein controls biofilm growth and virulence in Candida albicans. PLoS Biol. 2021, 19, e3000957.

- Koch, B.; Traven, A. Mitochondrial Control of Fungal Cell Walls: Models and Relevance in Fungal Pathogens. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2020, 425, 277–296.

- Duvenage, L.; Walker, L.A.; Bojarczuk, A.; Johnston, S.A.; MacCallum, D.M.; Munro, C.A.; Gourlay, C.W. Inhibition of Classical and Alternative Modes of Respiration in Candida albicans Leads to Cell Wall Remodeling and Increased Macrophage Recognition. mBio 2019, 10, e02535-18.

- Koch, B.; Tucey, T.M.; Lo, T.L.; Novakovic, S.; Boag, P.; Traven, A. The Mitochondrial GTPase Gem1 Contributes to the Cell Wall Stress Response and Invasive Growth of Candida albicans. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2555.

- Li, D.; Chen, H.; Florentino, A.; Alex, D.; Sikorski, P.; Fonzi, W.A.; Calderone, R. Enzymatic dysfunction of mitochondrial complex I of the Candida albicans goa1 mutant is associated with increased reactive oxidants and cell death. Eukaryot. Cell 2011, 10, 672–682.

- Bambach, A.; Fernandes, M.P.; Ghosh, A.; Kruppa, M.; Alex, D.; Li, D.; Fonzi, W.A.; Chauhan, N.; Sun, N.; Agrellos, O.A.; et al. Goa1p of Candida albicans localizes to the mitochondria during stress and is required for mitochondrial function and virulence. Eukaryot. Cell 2009, 8, 1706–1720.

- Sun, N.; Parrish, R.S.; Calderone, R.A.; Fonzi, W.A. Unique, Diverged, and Conserved Mitochondrial Functions Influencing Candida albicans Respiration. mBio 2019, 10, e00300-19.

- Heredia, M.Y.; Ikeh, M.A.C.; Gunasekaran, D.; Conrad, K.A.; Filimonava, S.; Marotta, D.H.; Nobile, C.J.; Rauceo, J.M. An expanded cell wall damage signaling network is comprised of the transcription factors Rlm1 and Sko1 in Candida albicans. PLoS Genet. 2020, 16, e1008908.

- Marotta, D.H.; Nantel, A.; Sukala, L.; Teubl, J.R.; Rauceo, J.M. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling and enrichment mapping reveal divergent and conserved roles of Sko1 in the Candida albicans osmotic stress response. Genomics 2013, 102, 363–371.

- Rauceo, J.M.; Blankenship, J.R.; Fanning, S.; Hamaker, J.J.; Deneault, J.S.; Smith, F.J.; Nantel, A.; Mitchell, A.P. Regulation of the Candida albicans cell wall damage response by transcription factor Sko1 and PAS kinase Psk1. Mol. Biol. Cell 2008, 19, 2741–2751.

- Skrzypek, M.S.; Binkley, J.; Binkley, G.; Miyasato, S.R.; Simison, M.; Sherlock, G. The Candida Genome Database (CGD): Incorporation of Assembly 22, systematic identifiers and visualization of high throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D592–D596.

- Wetzel, C.; Pifferi, S.; Picci, C.; Gok, C.; Hoffmann, D.; Bali, K.K.; Lampe, A.; Lapatsina, L.; Fleischer, R.; Smith, E.S.; et al. Small-molecule inhibition of STOML3 oligomerization reverses pathological mechanical hypersensitivity. Nat. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 209–218.