Breast cancer is one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality in women. Early breast cancer has a relatively good prognosis, in contrast to metastatic disease with rather poor outcomes. Metastasis formation in distant organs is a complex process requiring cooperation of numerous cells, growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines. Tumor growth, invasion, and finally systemic spread are driven by processes of angiogenesis, vasculogenesis, chemotaxis, and coagulation.

- breast cancer

- metastasis

- angiogenesis

- vasculogenesis

- chemotaxis

- coagulation

1. Introduction

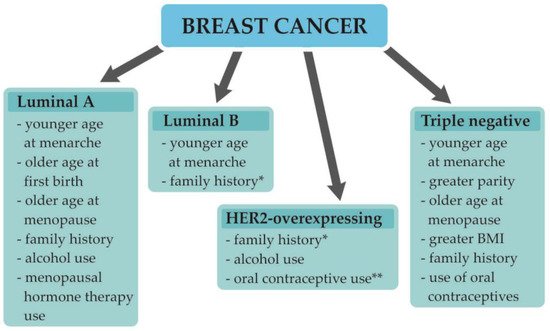

1.1. General Information Related to Breast Cancer

1.2. Understanding Breast Cancer Heterogeneity

| Luminal A-Like | Luminal B-Like | HER2- Overexpressing |

Triple-Negative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER | + | + | - | - |

| PR | ≥20% | <20% 1 | - | - |

| HER2 | - | + 1 | + | - |

| Ki-67 | <20% | ≥20% 1 | all | all |

| Grade | Low | Low/High | High | High |

| Frequency | 30–40% | 20–30% | 12–20% | 15–20% |

| Local–Regional Recurrence |

0.8–8% | 1.5–8.7% | 1.7–9.4% | 3–17% |

| Prognosis | Favorable | Intermediate | Unfavorable | Unfavorable/Poor |

Abbreviations: ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor 2; Ki-67, proliferation index; 1 and/or.

1.3. Breast Cancer Development, Progression, and Metastasis Formation

2. Angiogenesis

2.1. The Role of Angiogenesis in Tumor Invasion

2.2. The Role of Angiogenesis in BC

| Cytokines and Growth Factors Involved in Angiogenesis |

Role/Action |

|---|---|

| EGFR |

|

| bFGF |

|

| IL-8 |

|

| VEGF-A |

|

| TNF- α |

|

| MMPs |

|

Abbreviations: bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; VEGF-A, vascular endothelial growth factor A; IL-8, interleukin 8; MMPs, matrix metalloproteases; ECM, extracellular matrix; ECs, endothelial cells; BC, breast cancer; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.

2.3. Interactions of VEGF with Tumor and Tumor Microenviroment

2.4. Contribution of VEGF to the Metastatic Spread of BC

2.5. Structure of Tumoral Vessels

3. Vasculogenesis

3.1. Alternative Method of Tumor Vessel Formation

3.2. Role of EPCs in Breast Cancer

3.3. Role of Hypoxia and Inflammation in EPCs Mobilization and Homing

3.4. Interactions of EPCs with Tumor and Tumor Microenviroment

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biomedicines10020300