Bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) is a natural resource and a useful wild berry in Europe. Various parts of the plant contain many benefits for human health. The adaptation and secondary metabolism of V. myrtillus plants can be synergistically affected by a community of microbial endophytes.

- Vaccinium myrtillus L

- enzymatic activity

- endophytes

1. Introduction

Nutritional composition and antioxidant activity due to the abundance of phenolic compounds in leaves extracts are beneficial to human health [1][2]. The growing area of V. myrtillus is native to Europe, but this species is also found in temperate and sub-Arctic regions around the world. Bilberries are widely abundant and easily found in the forests of Lithuania, Latvia, Finland, and Norway. Well-drained, moist, acidic soils are best for this species, but it can also grow in very acidic soils (pH 4.5–6). Thus, the adaptation and secondary metabolism of V. myrtillus plants can be synergistically affected by microbial endophytes, the benefits and potential of which are, in many cases, unknown in wild forest plants. In addition, some endophytes have shown a good ability to colonize host plant tissues; therefore, bacteria have a beneficial effect on plant growth by providing plants with the necessary nutrients or bioactive compounds [3][4][5][6]. Many beneficial microorganisms from different plant species and environments have recently been identified that can act as sources of new bioactive compounds and can therefore be used in the medical, agricultural or food industries. Numerous microbiological and ecological studies have shown that plant endophytes and their products may be promising candidates as a biological control measure.

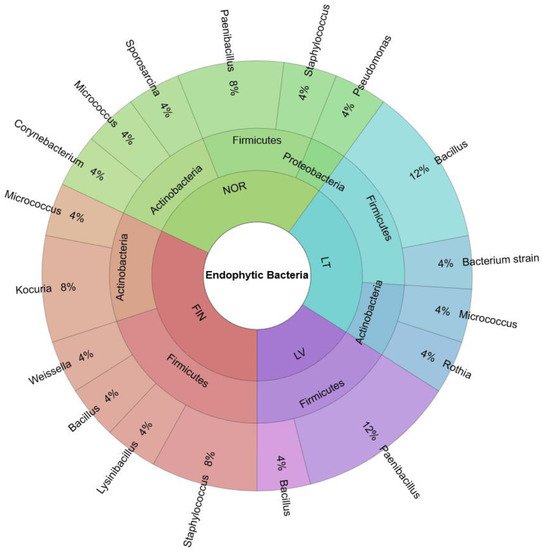

2. Biodiversity of Endophytic Bacteria in Bilberry Leaves

| Isolate | Accession Number in NCBI | Identity Accessions, According NCBI | Sequence Length, bp (Identity, %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bil-LT1_1 | MZ469297 | Bacillus halotolerans MK517597.1 B. mojavensis MF040286.1 B. velezensis MT634548.1 B. axarquiensis GU568194.1 B. subtilis AB526464.1 |

1437 (100) |

| Bil-LT1_2 | MZ469298 | Bacillus simplex LK391525.1 Peribacillus butanolivorans CP050509.1 |

1431 (100) |

| Bil-LT4_1 | MZ469299 | Rothia amarae MG905369.1 | 1400 (99.79) |

| Bil-LT4_3 | MZ469300 | Bacterium strain MTL8-4 MH151301.1 | 1439 (99.58) |

| Bil-LT4_7 | MZ469301 | Bacillus zhangzhouensis MN826587.1 B. pumilus CP054310.1 B. safensis KJ542766.1 B. stratosphericus KY203662.1 |

1420 (100) |

| Bil-LT4_8 | MZ469302 | Micrococcus sp. MG132043.1 M. luteus AJ409096.1 |

1398 (100) |

| Bil-LV3_1 | MZ469303 | Bacillus sp. strain MK736127.1 B. aryabhattai MN515130.1 B. megaterium MF988696.1 |

1427 (100) |

| Bil-LV3_3 | MZ469304 | Paenibacillus tundrae HF545335.1 | 1431 (100) |

| Bil-LV3_4 | MZ469305 | Paenibacillus sp. MK290403.1 | 1435 (99.65) |

| Bil-LV3_6 | MZ469306 | Paenibacillus sp. MG758020.1 | 1450 (99.86) |

| Bil-FIN2_3 | MZ469307 | Bacillus cereus MN068934.1 B. thuringiensis CP050183.1 |

1439 (100) |

| Bil-FIN-2_5 | MZ469308 | Staphylococcus warneri CP038242.1 S. pasteuri MW433878.1 |

1437 (100) |

| Bil-FIN2_6 | MZ469309 | Staphylococcus warneri CP038242.1 S. pasteuri MW433878.1 |

1437 (100) |

| Bil-FIN2_7 | MZ469310 | Lysinibacillus macrolides MH542661.1 L. xylanilyticus KP644237.1 L. fusiformis FJ641020.1 |

1427 (100) |

| Bil-FIN2_9 | MZ469311 | Kocuria kristinae KX055834.1 | 1384 (100) |

| Bil-FIN2_10 | MZ469312 | Weissella hellenica CP042399.1 | 1447 (100) |

| Bil-FIN2_12 | MZ469313 | Micrococcus terreus KJ781899.1 | 1385 (100) |

| Bil-FIN2_13 | MZ469314 | Kocuria kristinae KX055834.1 | 1384 (100) |

| Bil-NOR3_11 | MZ469315 | Staphylococcus sp. KM253075.1 | 1431 (100) |

| Bil-NOR3_13 | MZ469316 | Corynebacterium freneyi EF462412.1 | 1393 (99.86) |

| Bil-NOR3_14 | MZ469317 | Micrococcus sp. KX350143.1 M. luteus MN826463.1 |

1385 (100) |

| Bil-NOR3_15 | MZ469318 | Pseudomonas monteilii CP013997.1 | 1422 (100) |

| Bil-NOR3_16 | MZ469319 | Sporosarcina aquimarina MK726086.1 | 1433 (100) |

| Bil-NOR3_17 | MZ469320 | Paenibacillus xylanexedens CP018620.1 | 1436 (99.79) |

| Bil-NOR3_18 | MZ469321 | Paenibacillus sp. KR055031.1 | 1427 (99.86) |

3. Enzymatic-Genetic Features of Endophytic Bacteria in Bilberry Leaves

| Endophytic Bacteria Strains in Different Geographic Locations |

Amylolytic Activity, mm | Proteolytic Activity, mm | Catalase Reaction | Gene acdS | Gene AcPho |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus sp. Bil-LT1_1 | 11.9 ± 0.1 | 10.0 ± 0.1 | + | + | - |

| Bacillus sp. Bil-LT1_2 | + | - | - | ||

| Rothia amarae Bil-LT4_1 | 12.0 ± 0.2 | 11.8 ± 0.2 | + | - | - |

| Bacterium strain Bil-LT4_3 | 9.8 ± 0.1 | + | - | - | |

| acillus sp. Bil-LT4_7 | 9.0 ± 0.2 | 10.2 ± 01 | + | - | - |

| Micrococcus sp. Bil-LT4_8 | 9.3 ± 0.1 | + | - | - | |

| Bacillus sp. Bil-LV3_1 | 12.5 ± 0.1 | 14.2 ± 0.2 | + | - | - |

| Paenibacillus tundrae Bil-LV3_3 | 10.1 ± 0.2 | 11.9 ± 0.2 | + | - | - |

| Paenibacillus sp. Bil-LV3_4 | 12.1 ± 0.1 | 10.2 ± 0.1 | + | - | - |

| Paenibacillus sp. Bil-LV3_6 | 10.2 ± 0.1 | - | - | - | |

| Bacillus sp. Bil-FIN2_3 | 12.3 ± 0.2 | 14.3 ± 0.3 | - | + | + |

| Staphylococcus sp. Bil-FIN2_5 | + | - | - | ||

| Staphylococcus sp. Bil-FIN2_6 | 11.9 ± 0.2 | + | - | - | |

| Lysinibacillus sp. Bil-FIN2_7 | + | - | - | ||

| Kocuria kristinae Bil-FIN2_9 | + | + | - | ||

| Weissella hellenica Bil-FIN2_10 | - | - | - | ||

| Micrococcus terreus Bil-FIN2_12 | 9.5 ± 0.1 | + | - | + | |

| Kocuria kristinae Bil-FIN2_13 | 8.8 ± 0.1 | + | - | + | |

| Paenibacillus sp. Bil-NOR3_17 | 10.1 ± 0.2 | + | - | - | |

| Paenibacillus sp. Bil-NOR3_18 | + | - | - | ||

| Corynebacterium sp. Bil-NOR3_13 | 12.2 ± 0.1 | + | - | - | |

| Micrococcus sp. Bil-NOR3_14 | 10.3 ± 0.2 | 14.5 ± 0.2 | + | - | - |

| Staphylococcus sp. Bil-NOR3_11 | 10.1 ± 0.1 | + | - | - | |

| Pseudomonas monteilii Bil-NOR3_15 | + | - | - | ||

| Sporosarcina aquimarina Bil-NOR3_16 | + | - | - |

4. Summary

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/f12121647

References

- Bujor, O.; Le, B.C.; Volf, I.; Popa, V.I.; Dufour, C. Seasonal variations of the phenolic constituents in bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) leaves, stems and fruits, and their antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2016, 213, 58–68.

- Ziemlewska, A.; Zagórska-Dziok, M.; Nizioł-Łukaszewska, Z. Assessment of cytotoxicity and antioxidant properties of berry leaves as by-products with potential application in cosmetic and pharmaceutical products. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3240.

- Hardoim, P.R.; van Overbeek, L.S.; Elsas, J.D. Properties of bacterial endophytes and their proposed role in plant growth. Trends Microbiol. 2008, 16, 463–471.

- Hardoim, P.R.; van Overbeek, L.S.; Berg, G.; Pirttilä, A.M.; Company, S.; Campisano, A.; Döring, M.; Sessitsch, A. The Hidden World within Plants: Ecological and Evolutionary Considerations for Defining Functioning of Microbial Endophytes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2015, 79, 293–320.

- Singh, M.; Kumar, A.; Singh, R.; Pandey, K.D. Endophytic bacteria: A new source of bioactive compounds. 3 Biotech. 2017, 7, 315.

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Shao, Z.; Li, J.; Zan, S.; Zhou, S.; Yang, R. Two selenium tolerant Lysinibacillus sp. strains are capable of reducing selenite to elemental Se efficiently under aerobic conditions. J. Environ. Sci. 2019, 77, 238–249.