Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is characterized by a set of metabolic complications arising from adaptive failures to the pregnancy period. Estimates point to a prevalence of 3 to 15% of pregnancies. Its etiology includes intrinsic and extrinsic aspects the progenitress, which may contribute to the pathophysiogenesis of GDM. Recently, researchers have identified that the intestinal microbiota participates in the development of the disease, both through its influence on insulin resistance, as well as on pro-oxidant and pro-inflammatory products, which are potentially harmful to the health of the maternal-fetal binomial, in the short and long term.In this context, our objective was to gather evidence on the modulation of the intestinal microbiota, through the use of probiotics and prebiotics, with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, which can mitigate the endogenous processes of GDM, favoring the health of the mother and her children and , in a future perspective, to alleviate this critical public health problem.

1. Diabetes Mellitus Gestacional

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) reflects a set of endocrine complications arising from adaptive organ failure, considered the most common metabolic disorder of the pregnancy period

[1]. Its recognition occurs through the identification of spontaneous hyperglycemia, during pregnancy, and without precedents

[1][2]. Global estimates indicate that gestational hyperglycemia affects an average of 16.2% of pregnancies, among which 86.4% are due to GDM (

Box 1)

[3].

Box 1. Global and regional estimates of gestational hyperglycemia.

| Global Prevalence |

Prevalence by Region |

| Hyperglycemia in pregnancy |

16.2% |

Africa |

10.4% |

| Western Pacific |

12.6% |

| South America and Central America |

13.1% |

| North America and Caribbean |

14.6% |

| Europe |

16.2% |

| Middle East and North Africa |

21.8% |

| South East Asia |

24.2% |

| Source: Adapted from International Diabetes Federation [3]. |

The regions identified as those with the highest prevalence for the GDM have been low- and middle-income countries, where access to maternal health services is usually precarious or limited, with the Asian region being the one with the highest percentage (24.2%)

[3][4]. The disparities observed in the global epidemiological panorama may be due to the diagnostic criteria used, since there is still no consensus among organizations regarding the standardization of classification and diagnosis for the disease

[3].

1.1. Screening and Diagnosis

From the first reports to the present, there is no consensus between health organizations and entities regarding the diagnostic criteria for the GDM

[5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12]. Despite the divergences, the most commonly accepted criterion is the one of International Association of Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group (IADPSG)

[11], which was based on the study Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes (HAPO)

[9][13], establishing that pregnant women with changes in glucose parameters, identified during the 24th–28th gestational weeks, could be diagnosed with GDM (

Box 2)

[11].

Box 2. Diagnostic and screening criteria for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

| Criteria |

Time Course |

Fasting Glucose (mg/dL) |

Glucose Overload |

Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (mg/dL) |

| 1 h |

2 h |

3 h |

| O’Sullivan & Mahan (1964) [5] |

Detected at any time during pregnancy |

90 |

100 g of glucose |

165 |

145 |

125 |

O’Sullivan & Mahan (1964) [5]

adapted by National Diabetes Data Group (NDDG) (1979) [6] |

105 |

100 g of glucose |

190 |

165 |

145 |

Carpenter &

Coustan (1982) [7] |

95 |

100 g of glucose |

180 |

155 |

140 |

| World Health Organization (WHO) (1999) [14] |

126 |

75 g de

glucose |

Not

measured |

140 |

Not

measured |

| International Association of Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group (IADPSG (2010) [15] |

24-28

gestational weeks |

92 |

75 g de

glucose |

180 |

153 |

The American Diabetes Association (ADA), World Health Organization (WHO), Endocrine Society, and the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (IFGO) recommended the use of the criteria proposed by IADPSG

[16][17][18]. However, it is noteworthy that the diagnostic criteria established by the IADPSG expands the population of pregnant women diagnosed with GDM, reflecting health costs, in addition to not considering the risk factors in its screening, which could be a limiting factor

[19]. In Brazil, for instance, when comparing studies based on methodologies with different diagnostic criteria, it can be observed that the prevalence for GDM was about twice as high using the IADPSG criteria (18.0%) compared with the ones based on the first criterion established by the WHO (7.6%) [20][21].This increase in the prevalence of GDM may impact the country’s economy. In this sense, IFGO recommended that, in the presence of financial feasibility and technical availability, the IADPSG criteria should be used. However, it is the responsibility of each region to analyze and propose the adoption of the best diagnostic criteria for GDM, according to available resources [22]. The recent epidemiological and nutritional transition had negative impacts on the profile of nutritional status, eating habits, and sedentary lifestyle of the population. The adoption of screening of the risk factors for GDM should be considered, especially for health services with financial and technical limitations [19][22].

1.2. Etiology

GDM has well-documented risk factors, which include maternal chronological age, family history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), genetics, race/ethnicity, geography, socioeconomic status, DMG overweight, western-like diet, sedentary lifestyle, exposure to chemicals, polycystic ovary syndrome, vitamin D deficiency, and adverse birth conditions of the mother [3][23][24]. These risk factors are directly or indirectly associated with impaired β-cell function and/or insulin sensitivity. The Box 3 lists the mechanisms of action possibly related to the development of GDM.

Box 3. Risk factors attributed to the development of GDM

| Risk Factor |

Mechanism of Action |

Reference |

Advanced chronological age

(>35 years old) |

- Processes inherent to senescence:

-

During aging, the body can lose efficiency in repairing flaws or adapting to organic changes; thus, a late pregnancy can culminate in adaptive metabolic failure processes, contributing to resistance or decreased insulin sensitivity.

|

[25][26] |

| Family history |

- Family history for T2DM and the development of GDM:

-

During a normal pregnancy, more specifically in the third trimester, to meet the needs of fetal growth and development, maternal lipid metabolism changes (↓the activity of lipases, resulting in the increase (↑) of triglycerides (TG) and decrease (↓) of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c). After an adaptive period, they return to normal levels. However, there are failures in the feedback processes in pregnant women who develop GDM, which also occurs in T2DM.

|

[14][15] |

| Genetic factors |

- ▪ Genetic modifications shared between T2DM and GDM:

-

Some genes common in both T2DM and GDM correspond to genetic mutations related to decreased insulin secretion, such as genes CDK5 regulatory subunit-associated protein 1-like 1 (CDKAL1, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A/2B (CDKN2A/2B), and hematopoietically expressed homeobox (HHEX).

|

[40,41,42] |

- ▪ GDM-related genetic mutations:

-

Genetic mutations in some specific genes are related to the development of GDM, such as the following genes: transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2), CDKAL1, Transcription factor 2 (TCF2), Fat mass- and obesity-associated gene (FTO), CDKN2A/2B, HHEX, Insulin-like growth factor 2 MRNA binding protein 2, Solute carrier family 30 member 8 gene (IGF2BP2), and SCL30A8.

-

Some women, although uncommon among pregnant women with GDM, have genetic variants that are monogenic forms of diabetes, including genes for subtypes maturity onset diabetes of the young (MODY).

|

|

Race/

Ethnicity |

- Hispanic pregnant women would have greater chances of developing GDM, when compared with non-Hispanic ones, which can be considered a confonding factor when the geographic characteristics are inserted.

|

[31][32] |

| Geographic features |

- ▪

-

Depending on the territorial socio-economic limitation, which comprises government and population, data on the GDM may be under or overestimated since they depend on the diagnostic criteria adopted for screening the GDM, and, thus, on the financial and technical resources available in the country/region.

|

[12] |

| Socio-economic |

- ▪

-

Precarious socio-economic conditions, such as low income and education, and unemployment, may be related to worse gestational conditions, ↑ the risk for the development of GDM due to poor quality maternal care.

|

[33][34] |

| Overweight |

- ▪

-

Adipose tissue:

- -

-

It synthesizes adipokines, which can directly influence the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (interleukin 1β (IL-1β), nterleukin 6 (IL-6), and Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and contribute to the increase of serum levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and RONS. These factors favor the activation of the inflammatory cascade and, consequently, deregulate organic homeostasis, which may exacerbate the factors involved in the physiopathogenesis of GDM.

|

[35][36] |

- ▪

-

Positive energy balance:

- -

-

Caloric intake above daily needs, associated or not with a sedentary lifestyle, has an essential impact on insulin resistance, favoring the endogenous environment for the development of GDM.

|

[37][38] |

| Westernized diet |

- ▪

-

Dietary profile with high intake of red meat, sausages and ultra-processed products, refined products, sweets, pasta, and fried foods, also intensifies the mechanisms of insulin resistance, in addition to contributing to the underlying inflammatory process.

|

[39][19] |

| Sedentary lifestyle |

- ▪

-

The practice of physical activity reduces the chances of developing GDM by up to 46%, since a sedentary lifestyle, in turn, increases nitroxidative and inflammatory stress, and intensifies insulin resistance.

|

[40][41] |

| Exposure to chemicals |

- ▪

-

Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)—commonly found in cleaning products, some types of containers and packaging):

- -

-

Studies in animal models have found that their contact with offspring could, in a single gestational exposure, have potential effects on postnatal growth and development, causing a delay on them. Furthermore, there is evidence that it can be transmitted through lactation, causing harmful impacts to the health of the offspring.

- -

-

In humans, it was possible to identify a positive association between serum PFOA concentrations, with cholesterol, TG, and uric acid, which are related to pro-inflammatory pathways, and insulin resistance

|

[42][22][43][20][21][23] |

- ▪

-

Tobacco and alcohol:

- -

-

Independent risk factors for GDM, since its consumption may contribute to the endogenous increase in oxidative stress, inflammation, hyperglycemia and insulin resistance, although the exact mechanism of action has not yet been fully elucidated.

|

[24][25][26] |

| Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (POS) |

- ▪

-

Endocrine-metabolic disease that involves multiple hormonal changes related to female infertility, with symptoms such as insulin resistance, one of the most frequently observed, since approximately 50% of women with POS develop GDM during pregnancy.

|

[28][44] |

| Vitamin D Deficiency |

- ▪

-

Both vitamin D and parathormone (PTH) contribute to calcium (Ca) homeostasis. Vitamin D is responsible for the viability of the intestinal absorption of Ca, while PTH for maintaining Ca homeostasis in face of its deficiency. When serum Ca is at suboptimal concentrations, PTH stimulates Ca reabsorption from bone stores, and renal reabsorption, which could increase the risk of GDM, mediated by insulin resistance.

|

[29][30] |

Adverse birth conditions of the mother

(Fetal program) |

-

Mothers who were born in suboptimal conditions, such as premature, with Low birth weight (LBW), or small for gestational age (SGA), could trigger GDM in the pregnancy period, a theory known as fetal programming, postulated by Barker.

-

Changes in somatic growth due to the shortage of nutrients in the pregnancy period lead to damage to the hypothalamus/growth hormone; (GH)/Insulin-like growth (IGF-1) axis. A deficit in the morphology of target organs, such as the pancreas, reduces it in size and affects the function of pancreatic β-cells, culminating in the deficiency in insulin production.

- ▪

-

These conditions can lead to transgenerational effects, as a vicious cycle, causing serious consequences to public health.

|

[31][32][45][46][47] |

1.3. Maternal and Perinatal Outcomes in the GDM

The effects of GDM on maternal blood glucose are usually attenuated after removal of the placenta and return of serum hormone levels. However, pregnant women affected by GDM have an increased risk in the course of pregnancy for recurrent urinary infections, ketoacidosis, prolonged labor (difficulty in fetal passage through the vaginal canal, increasing the risk of using forceps) or cesarean, perineal lacerations or ruptures, uterine atony (condition in which the uterus cannot perform adequate contraction, with the possibility of postpartum hemorrhage), and uterine rupture (particularly in pregnant women with a previous history of cesarean section)

[48][49]. After the pregnancy period, these pregnant women have a seven-fold risk for the future development of T2DM and cardiovascular diseases (CVD) in addition to a higher rate for obesity and metabolic syndrome

[35][50][51].

As mentioned above, GDM can also cause complications to the fetus in an immediate and/or future perspective. Regarding immediate adverse outcomes (short term), it is possible to observe an increased risk for macrosomic birth (>4.000 g) or large for gestational age—LGA (relationship between birth weight (BW) and gestational age (GA) (BW/GA) > P90)), prematurity (GA at birth < 37 weeks), shoulder dystocia, hypoglycemia and/or hyperinsulinemia at birth, jaundice, neonatal abnormalities, and stillbirths

[35][48][49][52].

For macrosomic and LGA births, the Pedersen hypothesis, adapted by Freinkel, was widely accepted. It suggests that the increase in fetal size could possibly be a result of maternal hyperglycemia. This fact directly influenced the energy and fuel content of the fetus, mediated by the placenta, which may reflect in hyperinsulinemia. The increased availability of glucose and free fatty acids (fuels) via the placenta could stimulate the expression of type 1 insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1), which influences fetal growth, in addition to endogenous fetal insulin production

[53][54].

Hyperinsulinemia was suggested to stress the developing pancreatic β-cells, contributing to their dysfunction and insulin resistance, even if still in the uterine environment. This can cause fetal hypoglycemia

[35][52]. Additionally, fetal hyperinsulinemia seems to alter the synthesis of pulmonary surfactants, predisposing to respiratory distress syndrome, increasing neonatal morbidity rates

[55].

As for prematurity, its risk may be associated with rupture of uterine membranes. In addition, its complications can cause adverse outcomes, such as jaundice, respiratory and feeding difficulties, neonatal morbidity, and mortality, among others

[49]. As seen, jaundice can also be secondary to premature birth, but it can also be due to macrosomia. Macrosomic neonates need greater oxygen demand, possibly due to intrauterine fetal hypoxia with increased erythropoiesis and, consequently, polycythemia. When erythrocytes rupture, serum bilirubin concentrations increase, leading to neonatal jaundice

[48][49].

Regarding shoulder dystocia, its occurrence has been identified as one of the most severe perinatal complications, dealing with vaginal and birth trauma, with an increased risk of approximately 20 times for brachial plexus injuries

[56][57]. It is also noteworthy that the offspring is at potential risk of developing metabolic disorders in the immediate postpartum, probably due to the dependence formed by intrauterine hyperglycemia, which can contribute to brain damage

[35][50][58]. Finally, congenital anomalies can be influenced by the maternal hyperglycemic environment, which seems to cause severe damage to the development of fetal organs

[49].

Regarding future complications, i.e., in the long term, a recent and innovative line of research has emerged, with a series of studies aimed at investigating the transgenerational relationship between early environment and later adverse outcomes, seeking to understand the potential insights, recognized as fetal and epigenetic programming

[45][59]. These lines of research may explain the relationship between the easier development of metabolic disorders (as obesity), during childhood or early adulthood, with children from pregnancy with GDM

[60][61][62].

2. Intestinal Microbiota and GDM

The intestinal microbiota refers to all microorganisms that colonize the human gastrointestinal tract. Resident microorganisms have a symbiotic relationship with the host. They can extract energy from molecules that humans cannot digest, producing bioactive compounds and SCFA, which lead to several benefits to host metabolism. Therefore, the microbiota is currently considered an endocrine-metabolic organ, capable of controlling various organic processes

[63][64][65].

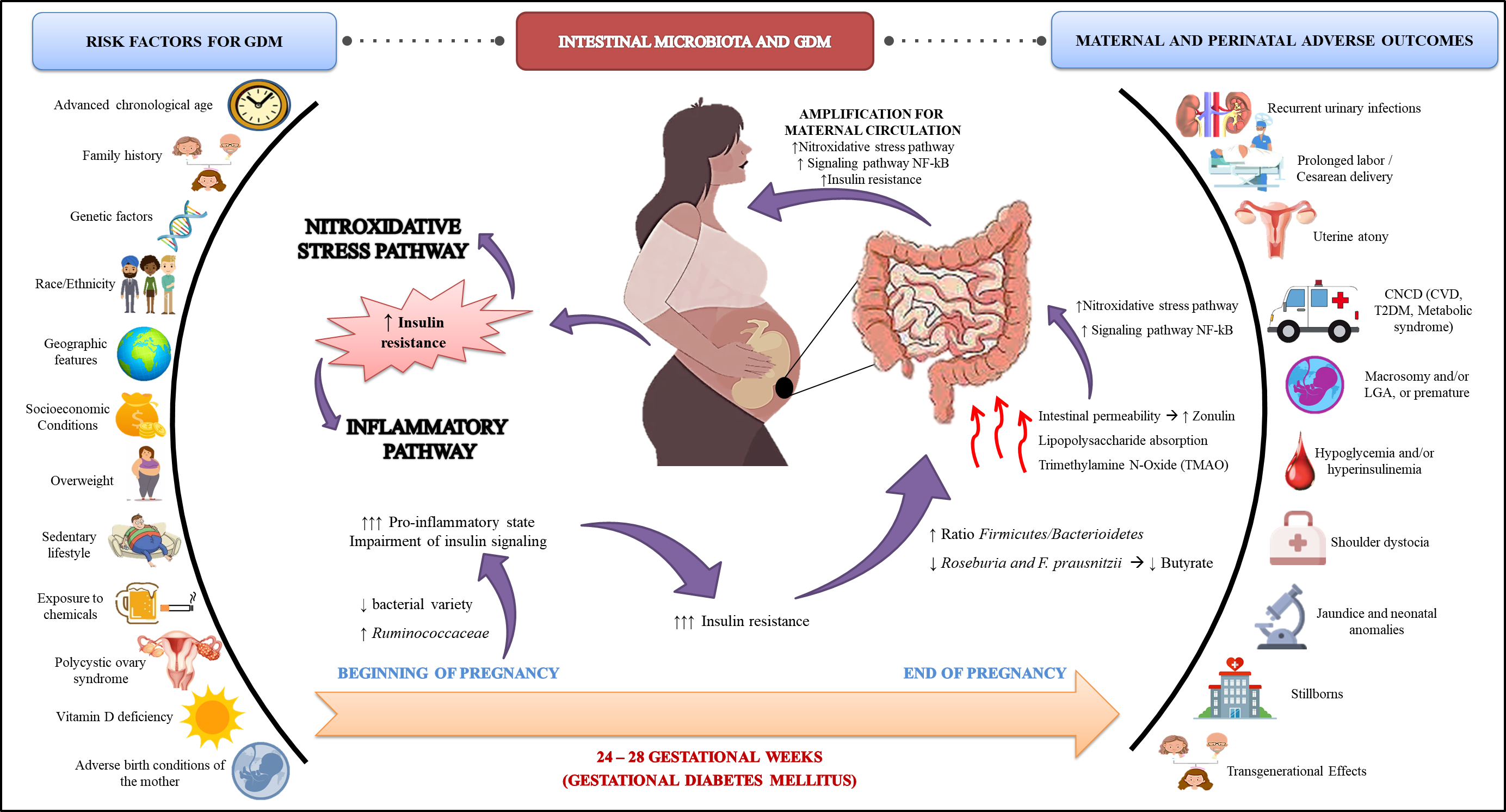

In turn, the change in the microbiota composition is called dysbiosis. This condition plays a crucial role in several pathogenic processes of metabolic diseases, such as obesity and diabetes mellitus. Among the mechanisms through which dysbiosis can compromise metabolism, there is an increase in intestinal permeability, increased LPS absorption, abnormal SCFA production, altered conversion of primary to secondary bile acids, and increased bacterial production of toxic substances such as trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO)

[66][67]. Thus, such changes lead to activating inflammatory processes and autoimmune pathways, autoantigen mimics, impaired insulin signaling, and others (

Figure 1)

[68].

Figure 1. Scheme of the interaction between GDM and intestinal microbiota, inflammatory, and oxidative stress processes.

Several factors can influence the composition of the microbiota, including early life events (genetic factors, premature birth, and breastfeeding), as well as future events (presence of comorbidities, diet composition, use of prebiotics and probiotics, use of antibiotics, and pregnancy)

[35][63]. In a healthy pregnancy, the microbiota undergoes several changes between the gestational trimesters. Studies show that healthy women at the end of pregnancy presented a microbiota composition similar to non-pregnant individuals with metabolic syndrome

[35][69].

The complex hormonal, immunological, and metabolic changes in the maternal organism promote maternal weight gain, increased concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and insulin resistance. However, reducing insulin sensitivity in healthy pregnancies is beneficial as it aims to promote fetal growth and to increase nutrient absorption

[35]. In GDM, marked insulin resistance promotes glucose intolerance. In general, insulin resistance is associated with a higher firmicutes/bacterioidetes ratio and a reduction in the amount of butyrate (an SCFA) producing bacteria, such as Roseburia and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii

[70][71]. However, it is unclear whether the altered microbiota is a cause or consequence of GDM

[63].

Data from the literature indicate a different composition of the microbiota in early pregnancy, before the development of GDM, since both conditions reduce the variety of bacteria and increase the Ruminococcaceae family, with a higher pro-inflammatory state and impaired insulin signaling

[35][72]. Furthermore, in GDM, intestinal permeability may improve, which is regulated by junction proteins such as zonulin (ZO-1); when it is accessible in plasma, it is associated with GDM

[73]. This fact can favor the movement of inflammatory mediators from the intestine to the circulation, promoting even more insulin resistance

[35][74].

A study conducted in women with GDM to assess the composition of the intestinal, oral, and vaginal microbiota, and its relationship with the disease, found a specific composition of the intestinal and vaginal microbiota, less diverse than the control group, suggestive of dysbiosis and indicating the involvement of these changes with the GDM

[75]. Corroborating this finding, through analyzes of the microbiota of the maternal (oral, intestinal and vaginal) and child (oral, pharyngeal, meconium and amniotic fluid) pairs, another study identified changes in the microbiota of the pairs belonging to the group with GDM, when compared with the control, namely lesser diversity and greater abundance of some viruses (herpesviruses and mastadenoviruses, for example)

[76]. Furthermore, the same trend was observed in maternal and neonatal changes in the GDM, reinforcing the intergenerational microbiotic agreement associated with the disease

[76].

It is essential to highlight that the microbiota of women with GDM can be transmitted to their fetuses. Thus, the knowledge of the composition and early microbiota modulation is exceptionally notorious. However, the link between dysbiosis, GDM, and inflammation has not been fully elucidated due to the scarcity of scientific studies

[76][63][77].

Considering that women who had GDM are at higher risk of having it again in subsequent pregnancies and T2DM, prevention strategies should be adopted, such as lifestyle modifications, including exercise and dietary changes, to better health outcomes. In addition, women with GDM who adopted dietary recommendations had reduced Bacteroides and better glycemic control

[78].

Furthermore, an alternative to be considered is the modulation of the microbiota in the GDM. Probiotics are microorganisms that promote health benefits to the host

[79]. Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus are the most widely used for this purpose

[80]. This procedure can promote the better composition of the intestinal microbiota; reduce the adherence of pathobionts; strengthen intestinal permeability; aid the immune response, insulin signaling, and energy metabolism; be a safe alternative, is well-tolerated, and has proven beneficial effects in various clinical conditions, including GDM. However, few clinical studies with probiotics are available in the literature in pregnant women, especially in GDM

[77].

Table 1 provides a qualitative summary of the clinical trials, which performed probiotic supplementation, alone or in combination, for the treatment of GDM.

Regarding the action of probiotics on inflammation in GDM, the literature is scarce. However, increasing evidence has shown beneficial effects of probiotic supplementation on intestinal health, from the attenuation of inflammatory processes and oxidative stress, by mechanisms that involve the inhibition of the NF-κB pathway, being characterized as a well-documented change in the GDM

[81][82]. Interestingly, probiotics exert acute biological effects, highlighting their antioxidant role, which remains controversial

[83]. In this sense, a study conducted in an animal model promoted probiotic supplementation in rats with GDM for 18 days. Serum levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), SOD, GR, and GPx showed that the antioxidant mixture reduced the induced oxidative stress

[84].

In addition to probiotics, intestinal modulation includes other factors, such as diet, capable of influencing the composition of the microbiota directly and indirectly. Some nutrients can directly interact with the microbiome and can stimulate the host’s metabolism and immune system, thus promoting changes in the microbiota

[63]. Few studies have evaluated the role of maternal nutrition on the microbiota during pregnancy. In general, high fiber consumption is associated with greater bacterial richness. On the other hand, low fiber consumption, associated with high consumption of fat, especially saturated, favors lower microbiota richness

[63].

In this context, a study observed the impact of diet on the intestinal microbiota in GDM. Women aged 24–28 weeks who received dietary recommendations and experienced up to 38 weeks of gestation were included. There was a significant reduction in the adherence of Bacteroides, which is associated with diets rich in animal fat. In addition, at baseline, total fat intake was associated with higher amounts of Alistipes and protein intake with

Faecalibacterium. On the other hand, at the end of the research, fiber consumption was associated with the genus

Roseburia. However, none of these bacteria were associated with the metabolic changes that occur in the GDM

[78].

Still, a study that evaluated fecal bacteria from women who had previous GDM reported a lower proportion of the

Firmicutes phylum and a more significant proportion of the Prevotellaceae family, compared with those with normoglycemia

[85]. Firmicutes metabolize dietary plant polysaccharides, which increase their levels. In turn, the consumption of animal protein and red meat promotes the intestinal reduction in

Firmicutes. Therefore, these bacteria seem to be relevant in the pathogenesis of GDM, regardless of diet, by still unknown mechanisms

[35]. Given the above, the need for further studies on the role of the microbiota in GDM is evident and the promising beneficial effects that probiotics can bring in this condition. Thus, the conduction of clinical trials of modulation of the microbiota and, with dietary manipulation strategies in the GDM, are significant to assess the possible use of these for the prevention and control of the disease. Furthermore, microbiota modulation is a potential therapy for GDM

[63].

Table 1. Randomized clinical trials with supplementation of probiotics, alone or in combination, for the treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus.

| Source Sample |

Population |

Size * |

Supplementation |

Dose/Duration |

Main Findings |

| Karamali et al. (2016) [86] |

Iran |

I: 30

C: 30 |

L. acidophilus + L. casei + B. bifidum |

2 × 109 CFU/

6 weeks |

Supplementation with probiotics ↓FBG, serum insulin, TG, and VLDL-c, and improved insulin resistance indexes. |

| Hajifaraji et al. (2018) [83] |

Iran |

I: 27

C: 29 |

L. acidophilus LA-5 + B. BB-12 + S. thermophilus STY-31 + L. delbrueckii bulgaricus + LBY-27 |

>4 × 109 CFU/

8 weeks |

Supplementation with probiotics significantly ↓CRP and TNF-α. MDA, GPx and GR in women in the intervention group. |

| Kijmanawat et al. (2019) [87] |

Thailand |

I: 28

C: 29 |

Bifidobacterium + Lactobacillus |

2 × 109 CFU/

4 weeks |

In women with diet-controlled GDM, supplementation with probiotics ↓FBG and insulin resistance compared with the control. |

| Babadi et al. (2018) [88] |

Iran |

I: 24

C: 24 |

L. casei + B. bifidum + L. fermentum + L. acidophilus |

2 × 109 CFU/

6 weeks |

Probiotic supplementation improved the expression of genes related to insulin; glycemic control; inflammation; lipid profile, and oxidative stress markers, such as ↓MDA and ↑TAC, compared with the control. |

| Badehnoosh et al. (2018) [89] |

Iran |

I: 30

C: 30 |

L. acidophilus + L. casei + B. bifidum |

2 × 109 CFU/

6 weeks |

Probiotic supplementation improved FBG, and CRP, ↑TAC, and ↓MDA, without affecting pregnancy outcomes. |

| Nabhani et al. (2018) [90] |

Iran |

I: 45

C: 45 |

L. acidophilus + L. plantarum + L. fermentum + L. gasseri + FOS |

1.5–7.0 × 109–10 CFU + 38.5 mg/

6 weeks |

Symbiotics had no effect on FBG and insulin resistance/sensitivity indexes. However, an ↑ in HDL-c and TAC was seen, and a ↓ was seen in blood pressure in the intervention group. |

| Jamilian et al. (2019) [91] |

Iran |

I: 29

C: 28 |

L. acidophilus + B. bifidum + L. reuteri + L. fermentum + Vitamin D |

8 × 109 CFU/

6 weeks

+50.000 UI

every 2 weeks |

↓FBG, serum insulin, CRP, and MDA; ↑TAC and GSH; and improved insulin resistance scores. |

| Karamali et al. (2018) [92] |

Iran |

I: 30

C: 30 |

L. acidophilus + L. casei + B. bifidum + Inulin |

2 × 109 CFU/

6 weeks

+800 mg |

Symbiotic supplementation ↓CRP and MDA; ↑TAC and GSH; and↓ the rates of cesarean section, hyperbilirubinemia and hospitalization in NB, without affecting other pregnancy outcomes. |

| Ahmadi et al. (2016) [93] |

Iran |

I: 35

C: 35 |

L. acidophilus + L. casei + B. bifidum + inulin |

2 × 109 CFU/

6 weeks

+800 mg |

Symbiotics ↑ insulin metabolism markers, and the insulin sensitivity index as well as ↓VLDL-c and TG. |

| Jafarnejad et al. (2016) [94] |

Iran |

I: 41

C: 41 |

S. thermophilus + B. breve + B. longum + B. infantis + L. acidophilus + L. plantarum + L. paracasei + L. delbrueckii subsp. Bulgaricus |

15 × 109 CFU/

8 weeks |

No differences were observed in FBG, glycated hemoglobin, serum insulin, and insulin resistance indices. However, ↓CRP, IL-6, and TNF-α were observed, without changes in IL-10 and IFN-γ. |

| Dolatkhah et al. (2015) [95] |

Turkey |

I: 29

C: 27 |

L. acidophilus LA-5 + B. BB-12 + Streptococcus thermophilus + STY-31 + L. delbrueckii bulgaricus LBY-27 |

>4 × 109 CFU/

8 weeks |

↓FBG and insulin resistance index, and less weight gain in those in the intervention group. |

| Lindsay et al. (2015) [96] |

Ireland |

I: 74

C: 75 |

L. salivarius |

1 × 10 9 UFC/

6 semanas |

Nenhum efeito benéfico no controle glicêmico ou resultados da gravidez. ↓ no total e LDL-c no grupo suplementado. |

* Pregnant with GDM; I: Intervention; C: Control; GDM: Gestational diabetes mellitus; ↑: Increase; ↓: Decrease; B: Bifidobacterium; FBG: Fasting blood glucose; FOS: Fructooligosaccharide; TG: Triglycerides; CRP: C-reactive protein; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor α; GPx: Glutathione peroxidase; GR: Glutathione reductase; GSH: Glutathione; HDL-c: High-density lipoprotein cholesterol; IFN-γ: Interferon gama; IL-6: Interleukin 6; IL-10: Interleukin 10; L: Lactobacillus; LDL-c: Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MDA: Malondialdehyde; TAC: Total antioxidant capacity; NB: Newborns; CFU: Colony forming unit; VLDL-c: Very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/antiox11010129