Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Short, intensive, but above lactate threshold physical trials or competitions which last <1 min but are close to this time limit, are on the border between glycolytic and aerobic efforts. The distribution of effort is critical in these tasks to achieve the best possible results. There are several approaches, grounded in the philosophical basis of effort, which determine effort distribution. The problem is still open and a clear direction has not yet emerged from the available studies on the topic.

- effort

- exhaustive exercise

- glycolytic metabolism

- termination of effort

- fatigue endpoint

- teleanticipation

- pacing strategies

1. Introduction

Glycolytic anaerobic metabolism was indicated as the limiting factor in several sport activities, and it was experimentally linked with fatigue and performance cessation. The limiting factors in humans, according to Nobel prize holder Arthur V. Hill [1], reside in the O2 transport system [2]. The role of volitional characteristics in determining the limits of performance has been evidenced, but it is not still clear [3][4] how it works in athletes. Because of the relatively recent interest of scientists in volition in sport, there is not a well-established base of knowledge on the topic [3]. The three main theories of volition are the theory of action control (ability to apply self-regulation strategies), the Rubicon model of action phases (the achievement of a point of no return which obligates one to continue the performance), and the strength model of self-control (volition) [3]. However, these three theories come from the general psychology domain and have been adapted to sport. Sports, by definition, are a broad range of activities, which are very different from each other. In sport activities, the process of fatigue in the performance of comparable duration and intensity (cycles per minutes) are very different among disciplines as they are affected by several factors. While in a long-distance run, a model such as the Rubicon model of action phases can work because there is sufficient time to think and adopt, adapt and/or change the running strategy, in short events the time for thinking is limited. In sport, a different specific explanation for the sustainability of physical effort and/or effort termination has been advocated. One performance where glycolytic pathway is mostly stimulated with less influence of any other confounding factors is during the 400 m dash run in track and field, thus, this can be assumed as a paradigm for maximal anaerobic effort [5]. Of special interest from a practical point of view, is the pacing strategies employed in the run. Until now, different recommendations for practice have been developed by scientists, grounded in different theories of fatigues.

2. Effort Distribution in Heavy Glycolytic Trials

2.1. Acidosis (pH), Lactic Acid (LA) and Limitations to Anaerobic Glycolytic Performance

The main explanation for the cessation of effort, which is historically given in the absence of other evidence, is that the acidosis likely deactivates the enzymes needed for energy production in the muscle. Peripheral blood lactate levels of 20.5 and 18.9 (±0.5) mm/L have been recorded 7 min post-race in Caucasian and African 400 m dash runners, respectively [5]. In another study, the measurement of muscle pH in the gastrocnemius of four subjects following a 400 m timed run on the track averaged 6.63 ± 0.03, while blood pH and HLa were 7.10 ± 0.03 and 12.3 mM [6]. The consumption of H+ ions resulting from the split of ATP or the depletion of phosphocreatine in working muscles [7] is the cause of acidosis. Lactic acid is toxic for the nervous system, causing dizziness, vision’s disturbances, and vagal reflexes (vomiting) at high concentrations [8]. The idea that limitations to performance happen mostly inside the muscle was supported by studies investigating the peripheral nervous system with Emg methods. Such studies showed that the causes of the end of performance are prevalently biochemical and happen in the working muscle [9]. Considering the 400 m run trial split into two 200 m segments, when observing the behavior of finalists (2017) of world IAAF (International Association of Athletics Federations) championships, both males and females showed an increase of speed up to 200 m, after which there is a remarkable linear decline of speed which continues until the end of the race [10]. The slope of this decline is more marked for males than for females. Equations considering the bioenergetics of the 400 m run have been proposed to model this drop in performance [11] and it has been found that the critical distance for running at maximal speed is 291 m. According to the mathematical model of Keller, until 291 m the race can be run at maximum propulsive speed, after this threshold, a distribution of effort must be adopted [11].

2.2. Pacing

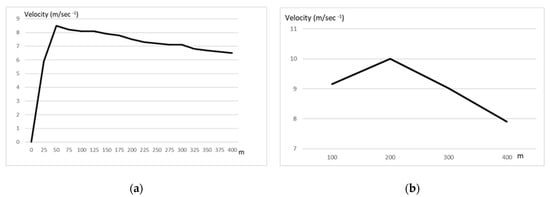

The idea of pacing in the fastest runs of track events is not new, and its popularity among coaches must be ascribed to the seminal work of Carlo Vittori in the 1970s and 1980s [12][13]. Models based on individual physiological (e.g., oxygen consumption, maximal speed, and performance in shorter distances e.g., 300 m) and psychological (albeit these characteristics have not been specified) characteristics were proposed for an optimal strategy [12] considering some individual differences. However, other possible parameters (e.g., enzymatic profile of the athletes) have not been investigated. Three different pacing behaviors can be observed: a positive pacing, which means that the second half of the competition is run with a higher time, negative pacing, which means that the time in the second split is decreasing, and an even pacing strategy. Given that the practical (for the field) determinant factor for a successful 400 m trial is the optimal distribution of effort, which also influences tactical choices [8][9], there were many studies which investigated the optimal distribution of effort in the 400 m race [10][14][12][13][15][16][17][18]. If we consider splitting the 400 m into two 200 m segments, or in shorter splits as depicted in Figure 1 (25 m), we can observe that after the first 50 m the velocity starts to decline. In addition, a different behavior can be noted in elite and sub-elite athletes.

Figure 1. Velocity profile in the 400 m dash, plotted every 25 m or every 100 m. (a) data from elite athletes every 25 m [19]. (b) data from elite athletes every 100 m [20].

As shown in Figure 1, the decline in velocity happens just after the first 50 m, if we consider the speed every 25 m as reported by Pollit [19] or after 200 m if we consider the 100 m segment [20].

With respect to oxygen consumption, a relatively high V˙O2 can be reached within 25 s from the start of a 400 m trial and the end V˙O2 values may be the consequence of metabolic perturbations correlated to the acidosis [21]. The athlete has to arrange their energy consumption per unit time with respect to the finishing point.

2.3. Teleanticipation

Pacing strategy has been proposed to be a teleanticipatory system, that is, a marker of underlying physiological systems, in which the brain anticipates the end point of exercise, and thus regulates the pace to avoid catastrophic derangements to homeostasis [22][23][24]. Anticipation concerns not only the basis of harmonic, biomechanically optimized motion, but also a teleanticipation for the optimal arrangement of exertion, which avoids early exhaustion before reaching a finish point [24]. The seminal work of Ulmer [23][25] modelled the teleanticipatory system as loop between afferent and efferent signals to/from the muscle which is mediated by the SNC in order to regulate the biomechanical and biochemical parameters of motion to optimize performance. Among basic electrochemical parameters, ETC (electron transport capacity) and redox potential have been shown to have a significant role [23]. This hypothesis was demonstrated by experiments in which the subjects did not know the end point of exercise and thus adopted different anticipatory strategies to avoid exhaustion and harm to homeostasis while optimizing performance [26]. The teleanticipation was postulated to have physical correlates in a central governor [27] (the so-called central governor model-CGM), a brain structure or a network of brain structures which integrates the afferent signals and regulates the strategy of pacing in an unconscious way, with the aim of maintaining homeostasis during running, according to the original idea of Ulmer [25] which was later developed by other authors [28][29]. However, the role of a central governor of exercise in the brain, has been questioned [30]. Shepard [30] states there is no evidence of such a center in the brain, and that self-regulation of pacing strategies happens as automatic responses to the exercise demands. Shepard argues that the CGM model is in contradiction with the Hill model of a “brainless” cardiovascular model, which grounded the exercise metabolism in mechanical regulations out of the brain’s integration control.

2.4. Brain and Perception of Effort

From experimental studies on runners, it seems that the brain uses a scalar timing mechanism to predict the end of a performance [31][32]. A standard measure of perceived exertion (the Borg RPE visuo-analog test [33]) scales with the proportion of exercise time that remains [31]. In fact, it has been shown that comparing the same runners in a half and full race of 13.1 miles, the RPE expressed against time did not change [31]. The same effect was observed in cycling [32]. In shorter efforts, lasting 15 to 240 s, has been shown that the major sensation of effort comes from the working muscles while central sensations from the body made only a relatively small contribution to overall effort perception [34]. This finding has been confirmed in another study which employed a 100 s isokinetic leg extension task, where the subjects informed of the endpoint time showed less fatigue than the ones who did not know the end point [35]. A similar experiment using a Wingate test showed a reduction in power output when the subject was deceived on the duration of the trial. Subjects who believed the trial was 30 s long (instead of the real 36 s) reduced their power output in the last 6 s, while those who did not believe this did not reduce their power output in the last 6 s of the 36 s trial. This was interpreted as the presence of a preprogrammed 30-s “endpoint” based on the anticipated exercise duration from previous experience [36]. Knowledge of the endpoint dealt to a conservative pacing strategy in longer distances (30 km) cycling, with a major activation of the prefrontal cortex in the brain, e.g., more thinking [37]. However, the fatigue resulting from a 30 km race is not qualitatively comparable to anaerobic glycolytic fatigue.

However, deception studies have been questioned, because the variables that can be manipulated (distance, time, cadence, environment, feedback, verbal encouragement) are manifold and there are few homogeneities in the studies which used deception techniques to study athlete responses [38]. The drops in power observed in the 30 s deception experiments solely reflect the drop in cadence, e.g., rhythmic capacity which is regulated by the brain. The rhythmogenesis of movement seems to be a subjective characteristic, which can be investigated and identified by using specific sensory-test batteries for rhythmic capacities [39]. However, behavioral anticipatory systems are widely diffused in nature. According to the definition of Robert Rosen, “An anticipatory system is a natural system that contains an internal predictive model of itself and of its environment, which allows it to change state at an instant in accord with the model’s predictions pertaining to a later instant” [40][41]. The model of Rosen [40][41], is based on “information”. As demonstrated experimentally [37][38][42], the athlete seems capable of constructing an internal surrogate for time as part of a model that can indeed be manipulated to produce anticipation, and this internal time runs faster than real time. The runner has a model of the future but does not have a definitive knowledge of the future itself. The present change of state is determined by an anticipated future state, working as a feedforward system [40] according to a model which is believed to be optimal for the task to be accomplished which is ultimately an encoding and decoding of information. This information comes from the internal (thinking, memory, efferent and afferents signals, diminished carbohydrate availability, elevated serotonin, hypoxia, acidosis, hyperkalemia, hyperthermia, dehydration and reactive oxygen species, lactate levels, maximal cardiac output [42]), and from the external (temperature, wind, surface, crowd, other competitors). Faulty encoding leads to faulty models of performance [40].

3. Conclusions

There is no convincing evidence to support or to contradict the existence of a CGM which regulates anaerobic glycolytic pacing effort. Thus, a behavioral perspective seems the most suitable to explain the pacing strategy. As a practical recommendation, it emerges from the study of existing relevant literature, that a tactical approach based on the contingent characteristic of the race (environmental conditions, previous eliminatory trials, knowledge of competitor´s strategies) and an individual athlete´s characteristics (endurance or sprint-oriented athlete) are the major determinants of success in the 400 m dash in track and field. However, the paradigm of mechanisms of exhaustion in heavy glycolytic trials can be extended to other human activities. These considerations can be extended, with a certain degree of accordance, to other activities requiring exhaustive glycolytic maximal effort, for example, in heavy physical work or in military operations. Further studies are necessary to elucidate the underlying mechanism of effort cessation because the literature is still unclear about the fundamental basis of fatigue. Furthermore, the existence of a central governor of effort based in the higher brain structures is still debated and unclear.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biology11020216

References

- Hill, A.V.; Lupton, H. Muscular Exercise, Lactic Acid, and the Supply and Utilization of Oxygen. QJM 1923, 16, 135–171.

- Jones, J.H.; Lindstedt, S.L. Limits to Maximal Performance. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1993, 55, 547–569.

- Beckmann, J.; Ehmann, M.; Kossak, T.; Perl, B.; Hähl, W. Volition in Sport. Z. Sportpsychol. 2021, 28, 84–96.

- Wolff, W.; Englert, C. On the Past, Present and Future of Volition Research in Sports. Z. Sportpsychol. 2021, 28, 81–83.

- Bret, C.; Lacour, J.R.; Bourdin, M.; Locatelli, E.; De Angelis, M.; Faina, M.; Rahmani, A.; Messonnier, L. Differences in lactate exchange and removal abilities between high-level African and Caucasian 400-m track runners. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2013, 113, 1489–1498.

- Costill, D.L.; Barnett, A.; Sharp, R.; Fink, W.J.; Katz, A. Leg muscle pH following sprint running. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1983, 15, 325–329.

- Allen, D.G.; Lamb, G.D.; Westerblad, H. Skeletal muscle fatigue: Cellular mechanisms. Physiol. Rev. 2008, 88, 287–332.

- van Hall, G. Lactate kinetics in human tissues at rest and during exercise. Acta Physiol. 2010, 199, 499–508.

- Nummela, A.; Vuorimaa, T.; Rusko, H. Changes in force production, blood lactate and EMG activity in the 400-m sprint. J. Sports Sci. 1992, 10, 217–228.

- Casado, A.; Hanley, B.; Jiménez-Reyes, P.; Renfree, A. Pacing profiles and tactical behaviors of elite runners. J. Sport Health Sci. 2021, 10, 537–549.

- Keller, J.B. A Theory of Competitive Running. Phys. Today 1973, 26, 42–47.

- Martin-Acero, R.; Rodriguez, F.A.; Codina-Trenzano, A.; Jimenez-Reyes, P. Model for individual pacing strategies in the 400 metres. New Stud. Athl. 2017, 32, 27–44.

- Vittori, C. The development and training of young 400 m runners. New Stud. Athl. 1991, 6, 35–46.

- Reardon, J.C. Optimal Pacing for Running 400 m and 800 m Track Races. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1204.0313 (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Saraslanidis, P.J.; Panoutsakopoulos, V.; Tsalis, G.A.; Kyprianou, E. The effect of different first 200-m pacing strategies on blood lactate and biomechanical parameters of the 400-m sprint. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 111, 1579–1590.

- Coppenolle, H. Analysis of 200 m intermediate times for 400 m world class runners. Track Field Quaterly Rev. 1980, 80, 37–39.

- Wyatt, R.; Gunby, P. Optimal Pacing of 400 m and 800 m Races; A Standard Microeconomics Approach. Working Paper 12/2016. Available online: https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/handle/10092/15227 (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Hanon, C.; Claire Thomas, C. Effects of optimal pacing strategies for 400-, 800-, and 1500-m races on the V_O2 response. J. Sports Sci. Taylor Fr. SSH J. 2011, 29, 905–912.

- Pollitt, L.; Walker, J.; Tucker, C.; Bissas, A. Biomechanical Report for the IAAF World Championships in London. 400 m Men’s. Available online: https://www.worldathletics.org/about-iaaf/documents/research-centre (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- German Athletic Federation. Biomechanical Analysis of Selected Events at 12 IAAF World Championship, Berlin 2009. Available online: https://www.bing.com/search?q=20.%09German+Athletic+Federation.+Biomechanical+analysis+of+selected+events+at+12+IAAF++World+Championship%2C+Berlin+2009.+&form=ANNTH1&refig=18647e74c80d4e018140b30978b713da (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Hanon, C.; Lepretre, P.-M.; Bishop, D.; Thomas, C. Oxygen uptake and blood metabolic responses to a 400-m run. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 109, 233–240.

- Tucker, R.; Noakes, T.D. The physiological regulation of pacing strategy during exercise: A critical review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009, 43, e1.

- Ulmer, H.V. Concept of an extracellular regulation of muscular-metabolic rate during heavy exercise in humans by psychophysiologial feedback. Experimentia 1996, 52, 416–420.

- Edwards, A.M.; Bentley, M.B.; Mann, M.E.; Seaholme, T.S. Self-pacing in interval training: A teleoanticipatory approach. Psychophysiology 2011, 48, 136–141.

- Ulmer, H.V.; Schulze, H. Zeitbezogene Zielantizipation als Teil motorischen Lernens bei 1- bis 10-miniitiger Haltearbeit. In Motodiagnostik-Mototherapie; Scholle, H.-C., Struppler, A., Freund, H.-J., Hefder, H., Schumann, N.P., Eds.; Universitgtsverlag Jena: Jena, Germany, 1995; pp. 311–315.

- Yamamoto, K.; Miyashiro, K.; Naito, H.; Kigoshi, K.; Tanigawa, S.; Byun, K.O.; Miyashita, K.; Ogata, M. The relationship between race pattern and performance in the men’s 400-m sprint. Taiikugaku Kenkyu Jpn. J. Phys. Educ. Health Sport Sci. 2014, 59, 159–173.

- Noakes, T.D. Is it Time to Retire the A.V. Hill Model? Sports Med. 2011, 41, 263–277.

- Shephard, R.J. Is it time to retire the ‘central governor’? Sports Med. 2009, 39, 709–721.

- Marino, F.E. If only I were paramecium too! A case for the complex, intelligent system of anticipatory regulation in fatigue. Fatigue Biomed. Health Behav. 2014, 2, 185–201.

- Noakes, T.D.; Peltonen, J.E.; Rusko, H.K. Evidence that a central governor regulates exercise performance during acute hypoxia and hyperoxia. J. Exp. Biol. 2001, 204, 3225–3234.

- Faulkner, J.; Parfitt, G.; Eston, R. The rating of perceived exertion during competitive running scales with time. Psychophysiology 2008, 45, 977–985.

- Eston, R.; Stansfield, R.; Westoby, P.; Parfitt, G. Effect of deception and expected exercise duration on psychological and physiological variables during treadmill running and cycling. Psychophysiology 2012, 49, 462–469.

- Borg, G.A.V. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1982, 14, 377–381.

- Cafarelli, E.; Cain, W.S.; Stevens, J.C. Effort of Dynamic Exercise: Influence of Load, Duration, and Task. Ergonomics 1977, 20, 147–158.

- Hamilton, A.R.; Behm, D.G. The effect of prior knowledge of test endpoint on non-local muscle fatigue. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 117, 651–663.

- Wingfield, G.; Marino, F.; Skein, M. The influence of knowledge of performance endpoint on pacing strategies, perception of effort, and neural activity during 30-km cycling time trials. Physiol. Rep. 2018, 6, e13892.

- Ansley, L.; Robson, P.J.; St Clair, G.A.; Noakes Timothy, D. Evidence for anticipatory pacing strategies during supramaximal exercise lasting more than 30 s. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2004, 36, 309–314.

- Jones, H.S.; Williams, E.L.; Bridge, C.A.; Marchant, D.; Midgley, A.W.; Micklewright, D.; Mc Naughton, L.R. Physiological and psychological effects of deception on pacing strategy and performance: A review. Sports Med. 2013, 43, 1243–1257.

- Seashore, R.H. Studies in motor rhythm. Psychol. Monogr. 1926, 36, 142–189.

- Louie, A. Robert Rosen’s anticipatory systems. Foresight—The journal of future studies strategic thinking and policy. Foresight 2010, 12, 18–29.

- Rosen, R. Anticipatory Systems: Philosophical, Mathematical & Methodological Foundations; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1985.

- Knicker, A.J.; Renshaw, I.; Oldham, A.R.; Cairns, S.P. Interactive processes link the multiple symptoms of fatigue in sport competition. Sports Med. 2011, 41, 307–328.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!