Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Genetics & Heredity

The piRNAs correspond to a class of small non-coding RNAs interacting with the PIWI proteins (Piwi, Aub, and Ago3 in Drosophila), belonging to the AGO subfamily proteins, mainly active in animal gonads to protect genome integrity against TEs.

- piRNA

- environment

- transgenerational epigenetics

1. Overview of piRNA Biogenesis and Functions

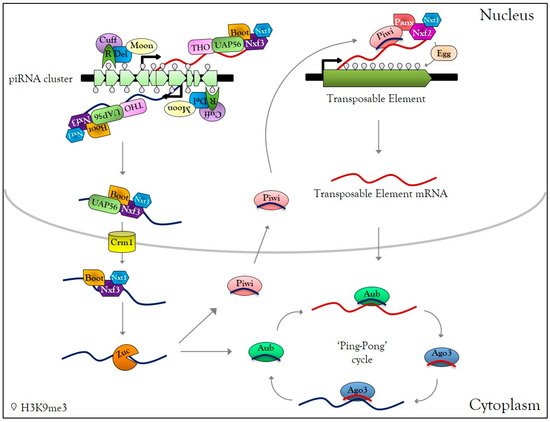

In Drosophila germ cells, piRNAs are produced from specific heterochromatic loci, composed of numerous TE fragments, called piRNA clusters [74,75]. Those clusters are enriched in the H3K9me3 mark and Rhino HP1-like protein [76] (Figure 1). Rhino interacts first with the co-factors Deadlock and Cutoff, then Deadlock recruits the transcriptional initiation machinery via the large subunit of transcription initiation factor II A (TFIIA-L) paralog called Moonshiner, as well as Bootlegger, UAP56, the THO complex, and nuclear export factors Nxt1 and Nxf3 [76,77,78,79]. The piRNA precursor transcripts emerging from piRNA clusters are then exported by the Crm1 (chromosomal maintenance 1) exportin to the cytoplasmic piRNA biogenesis site, where they undergo a single strand hydrolysis by the Zucchini RNase to finally give rise to piRNAs [78,79,80,81,82,83] (Figure 1). In contrast to si- and miRNA, piRNAs are charged directly as single guide RNA onto PIWI proteins to form piRNA-induced silencing complexes (piRISC) [74]. After nuclear translocation, piRISC complexes recognize nascent TE transcripts and perform transcriptional gene silencing (TGS) by local heterochromatinization of TEs. This silencing requires nuclear Piwi-piRNAs that direct Panoramix, Nxf2, its co-factor, Nxt1, and the histone methyltransferase Eggless to the TE loci [84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91] (Figure 1). In the cytoplasm, mRNAs of TEs are cleaved by piRISC complexes, leading to post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) of mobile elements. Cleaved-transcripts are not degraded; they are charged by PIWI protein to form new piRISC complexes, corresponding to an amplification mechanism called the ‘Ping-Pong cycle’ [74] (Figure 1). piRNA-dependent silencing occurs at each gonadal developmental stage [92], and disruption of the piRNA pathway leads to TE mobilization [93], which induces DNA damage [94,95].

Figure 1. Germline PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNA) biogenesis. In Drosophila melanogaster germ cells, active piRNA clusters are enriched in H3K9me3 and HP1-like protein Rhino (R), which interact with Deadlock (Del), Cutoff (Cuff). Moonshiner (Moon) interacts with Del and recruits transcription initiation factors, allowing transcription of piRNA clusters in the sense and antisense direction. Bootlegger, UAP56, the THO complex, Nxt1, Nxf3 are recruited to the piRNA cluster transcription site. The transcripts are then exported to the cytoplasmic piRNAs biogenesis site via the CRM1 exportin. In the cytoplasm, piRNA precursors are cleaved by Zucchini (Zuc) into primary piRNA and charged by Piwi or Aubergine (Aub) proteins, forming Piwi-piRISC and Aub-piRISC complexes. Piwi-piRISC is translocated into the nucleus and recognizes nascent TE transcripts due to the interaction with Panoramix, the Nxf2, and Nxt1. The association of these factors to nascent TE transcripts causes recruitment of the histone methyltransferase Eggless that transcriptionally silences TEs by local heterochromatinization. In the cytoplasm, Aub-piRISC cleaves TE transcripts into secondary piRNAs, which are loaded onto Ago3, forming Ago3-piRISC complexes. Ago3-piRISC recognizes and cleaves piRNA precursors into new secondary piRNAs, loaded onto Aub. This mechanism, known as the ‘Ping-Pong’ cycle, allows the amplification of piRISC complexes and post-transcriptional regulation of TEs.

PIWI protein distributions reveal that the piRNA pathway is highly conserved in animals, but they exist neither in plants nor in prokaryotes [96]. Interestingly, recent studies show that piRNAs are also found in somatic tissues of mammalian, arthropods, and mollusks [97,98,99,100]. In Drosophila melanogaster, however, piRNA expression is restricted to the gonads, including the germline nurse cells and the somatic follicular cells [101,102]. These findings might suggest that the ancestral capacity to synthesize piRNAs in somatic tissues (outside of gonads) has been lost in D. melanogaster. However, this is still subject to debate [103,104,105].

2. Role of piRNAs Outside of Transposable Element Regulation

Genomic annotations of small RNA libraries isolated from various metazoans reveal that piRNAs are not restricted to TE regulation but can also target coding genes. In Drosophila, piRNAs derived from the 3′UTR of traffic-jam (tj) matching Fasciclin III (FasIII) can be identified in the ovarian somatic cells (OSC) line. This finding suggests that FasIII is regulated by piRNAs originated from the tj 3′UTR [102,106]. In Drosophila early embryos, nanos (nos) is regulated by piRNAs. Evidence suggests that maternal nos mRNAs are targeted by a complex composed of piRNAs, Aub, and CCR4-NOT deadenylation factors in the soma, whereas in the germ plasm, those transcripts are stabilized by the interaction with Aub [107,108]. In Aplysia, piRNAs seem to be implicated in CREB2 promoter methylation, a transcriptional repressor involved in long-term memory [109]. As the last example, sex determination in silkworm is dependent on the piRNA pathway that regulates Masculinizer, a locus required for the production of the doublesex female-specific isoform [110]. Taken together, these data highlight the idea that piRNAs are required in gene regulation of a broad range of cellular functions.

3. piRNAs in Epigenetic Memory

In Drosophila, the insertion of exogenous lacZ sequences into a subtelomeric piRNA cluster can functionally repress a euchromatic lacZ transgene in trans [111]. This epigenetic silencing mechanism, referred to as the trans-silencing effect (TSE), requires maternally but not paternally inherited piRNAs [71,112,113,114,115,116]. These results strongly suggest an active role for piRNAs in TSE and show that a piRNA cluster, without maternal piRNA inheritance, is not sufficient to promote this silencing process [112]. Involvement of piRNAs in epigenetic memory has been associated with epiallele emergence through a paramutation phenomenon in D. melanogaster and in C. elegans [71,117]. Paramutation is defined as a modification of one allele induced by another allele without DNA sequence modification and corresponds to an epigenetic conversion (for reviews see [118,119,120].

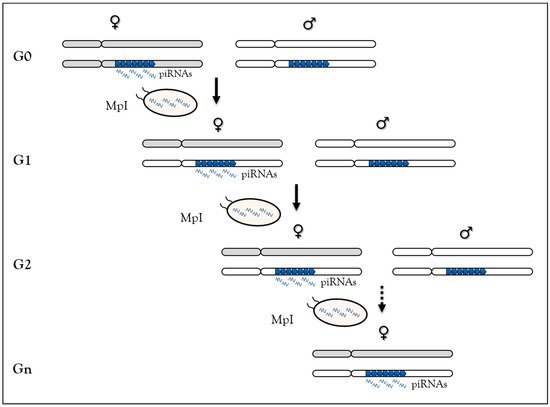

In Drosophila, using a locus made of repeated P-lacZ-white transgenes mimicking a piRNA cluster (called BX2 cluster), but inactive for piRNA synthesis, we have shown that homologous maternally-inherited piRNAs can stably convert this locus into an active piRNA cluster for over 200 generations [71] (Figure 2). This newly-activated cluster has the same properties as other Drosophila piRNA clusters. This piRNA-induced paramutation process requires molecular actors of the piRNA pathway [72] and performs TE-derived sequence control generation after generation. Finally, the reversibility of paramutation occurs when maternal piRNA inheritance is interrupted, underscoring the idea that this is an epigenetic process [26,71]. Taken together, based on sequence complementarity, these data show that maternally-inherited piRNAs are competent to initiate new piRNA production in the next generation and suggest that piRNAs are responsible for their own maintenance across generations. Two non-exclusive molecular mechanisms have been proposed to explain this case of epigenetic memory in which piRNA production requires piRNA inheritance [121]. In the first, inherited-piRNAs would induce heterochromatin formation on the piRNA cluster by leading to H3K9me3 deposition, inducing local Rhino enrichment [26]. The piRNA cluster-specific transcription machinery will then assemble at the locus to promote piRNA synthesis [77]. In the second, inherited piRNAs could trigger their production by Ping-Pong amplification from piRNA cluster precursors and TE transcripts [74,75].

Figure 2. The paramutation process in Drosophila melanogaster relies on maternal piRNA inheritance. At G0, females (grey chromosomes) carrying the BX2 clusters made of repeated P-lacZ-white transgenes (blue arrowheads) producing piRNAs are crossed to males (white chromosomes) carrying the same cluster not producing piRNA. At G1, maternal piRNA deposition in the embryo leads to activation of piRNA production from the paternal cluster allele. The newly activated cluster can activate the paternally-inherited inactive cluster in G2 due to maternal piRNA inheritance (MpI). Then, this process of activation leads to stable piRNAs production across generation.

In C. elegans, piRNAs correspond to 21 nucleotide (nt) long small RNAs with a uridine bias at the 5′-end (21U RNA) distinct from the endo-siRNAs that are 22 nt long small RNAs with a guanosine bias at the 5′-end (22G RNA) [122]. The biogenesis of nematode piRNAs depends on the Piwi protein, PRG-1 [66,123,124]. Like in Drosophila, transgenes are used to decipher the molecular mechanisms of germline repression. Analysis of the piRNA sensor indicates that piRNAs are required to trigger silencing through imperfect base-pairing [125,126,127]. This silencing is then transgenerationally propagated by the 22G RNA dependent on numerous factors, such as RdRp, NRDE-2, the Argonaute proteins WAGO-9/HRDE-1 and WAGO-4 and chromatin components, such as the histone methyltransferases SET-25, SET32, and HPL-2, a Heterochromatin 1 Protein (HP1) orthologue [45,128,129,130,131,132,133]. Indeed, specific H3K9 methyltransferases, SET-25 and SET-32, and endo-siRNAs have been shown to work together to promote silencing inheritance [134]. In addition, neuronal RDE-4 and germline HRDE-1 have been implicated in transgenerational regulation of endo-siRNAs and mRNAs controlling chemotaxis [135]. The authors proposed the existence of an intricate interaction between the neuronal system and the germline to control transgenerational behavior. Finally, precise dissection of the silencing mechanism determines that piRNAs lead to the production of secondary and tertiary siRNAs, necessary for full repression and leading to an epigenetic conversion form of paramutation [67].

4. Heritable Stress-Induced piRNA Synthesis

In F0 mice, an early maternal separation causes downregulation of piRNA cluster 110 [139], and a Western-like diet leads to differential expression of 190 piRNAs distributed on 63 piRNA clusters [140]. In rat, a high-fat diet induces deregulation of 1092 piRNAs, and only three of them are still differentially expressed at the next generation [141]. In C. elegans, high temperature (25 °C) induces motif-dependent piRNA biogenesis downregulation [142]. This downregulation is associated with differential gene expression and fitness reduction, which persist at the next generation. However, in those studies, piRNA expression in subsequent generations, as well as their roles in a phenotypic response and the potential consequences on the epigenome, was not directly addressed. In the case of rat stressed with vinclozolin or DDT, differentially expressed piRNAs were identified in F3, but the mechanism and role of piRNAs were not questioned [20,21,22,23,25].

In 2019, two cases of environmental stresses inducing a genomic response dependent on piRNAs have been published in C. elegans and in D. melanogaster [26,46].

4.1. Behavior in C. elegans

Wild type male or female larvae of C. elegans exposed to pathogenic Pseudomonas aeruginosa learn to avoid it and switch their feeding preference to nonpathogenic bacteria. This learning to distinguish between pathogen and non-pathogen does not correspond to a general phenomenon but rather is specific for P. aeruginosa [46]. Surprisingly, this behavior of avoidance can be transgenerationally inherited to the naïve F1 progeny up to the fourth generation (F4). This peculiar inheritance is completed at the fifth generation, where progeny exhibits a naïve behavior. Differential transcriptome analyses were performed on treated vs. non-treated mothers fed with pathogenic P. aeruginosas and their respective progeny. Moore and colleagues showed that the TGF-β ligand DAF-7, previously identified as a neuronal responder of the pathogen [143], was expressed more in specific sensory neurons of treated mothers relative to non-treated animals as well as in the F1, F2, F3, and F4 progeny, thus mirroring transgenerational avoidance [46]. The authors further show that in the daf-7 loss of function mutant, while the mother can learn to avoid the pathogen, the F1 progeny did not receive the information of avoidance. The same pattern of inheritance was observed for mother defective for the Piwi encoding gene prg-1. This mutation is associated with a defect in piRNA expression in the mothers and in daf-7 induction in the ASI neurons in F1.

Altogether, these studies indicate that transgenerational inheritance involved in the avoidance of pathogenic P. aeruginosa depends on the TFG-β pathway linked to the small non-coding RNAs as well as piRNA molecular partners. Therefore, piRNAs might participate in the control of specific reversible behaviors, which might have consequences on adaptive survival, providing advantages to progeny. In addition, the loss of inheritance after five generations might be considered an advantage in worms that may colonize a new environment in their natural habitat. The precise molecular basis of this resetting occurring at the fifth generation was not addressed but might be reminiscent with previous studies [63].

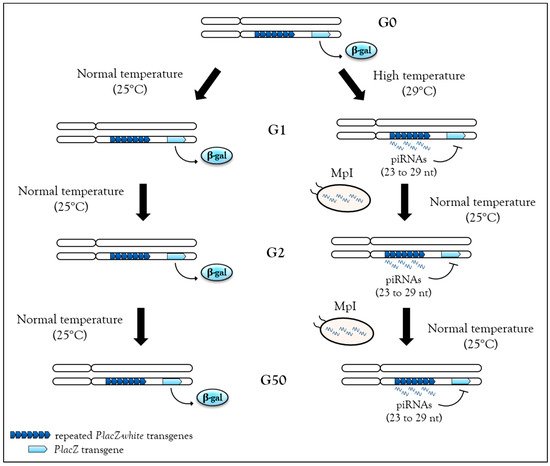

4.2. Heat Response Induces de novo piRNAs

Recently, high temperature during development (29 °C instead of 25 °C) has been shown to be sufficient to induce de novo piRNA production and heterochromatin associated with H3K9me3 and Rhino enrichment from the BX2 cluster in Drosophila [26]. One generation raised at 29 °C is sufficient to activate piRNA production from the BX2 cluster, and once this production is started, it can be maintained over 50 generations even after return to normal temperature (25 °C) (Figure 3). These piRNAs can functionally silence homologous lacZ reporter transgenes, a phenomenon referred to previously as TSE. Hence, heat stress is able to induce piRNA production from a locus comprised of repeats. Once established, this production remains stable even after stress removal, i.e., when flies return to a normal temperature of 25 °C. Small RNA sequencing analyses were unable to identify other genomic loci used for de novo piRNA synthesis as if all loci competent to become piRNA cluster were already activated. Analyses performed at 29 °C to identify molecular factors required for the activation of de novo piRNA production suggest that there is an increase of transcription of the BX2 cluster flanking region along with the transcription of a homologous euchromatic sequence. When BX2 is maternally inherited, piRNA production is maintained, but when BX2 is paternally inherited, piRNA production is abolished. This result suggests that when the stress is removed, piRNA can be self-maintained over generations by the paramutation process, as long as the inheritance is maternal [26] (Table 1).

Figure 3. Stable, heritable stress-induced de novo piRNAs. In flies, the BX2 cluster, a sequence made of repeated P-lacZ-white transgenes (dark blue arrowheads), is capable of producing piRNA after one generation at 29 °C, then these piRNAs can functionally repress a homologous P-lacZ sequence (light blue arrowheads) in trans. This silencing capacity is maintained at the second generation after return to normal temperature (25 °C) and then up to 50 generations. Hence, when stress is removed, piRNAs can be self-maintained by maternal piRNA inheritance (MpI) at each generation.

In Drosophila, environmental stresses can generate piRNA emergence, and this new piRNA production is maintained across generations, allowing stable repression of homologous sequences. How can environmental stress impact piRNA production? It remains unclear whether piRNA cluster chromatin containing H3K9me3 marks, piRISC complex formation and/or stability, or piRNA pathway genes are involved in the stress response, individually or simultaneously. To date, it is quite difficult to estimate the global effect of piRNA deregulation over many generations, in particular, if it might result in the alteration of inherited gene expression patterns. Future investigations will help our understanding of environmentally-induced piRNA transgenerational inheritance and allow the estimation of potential consequences.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cells8091108

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!