Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Mycology

Ramularia leaf spot (RLS), caused by the fungus Ramularia collo-cygni, has recently become widespread in Europe. Succinate dehydrogenase inhibitor (SDHI) and demethylation inhibitor (DMI) fungicides are mainly applied for disease control on barley fields, but pathogen isolates with a reduced sensitivity can cause difficulties. There is an urgent need for new spring barley cultivars that are more resistant to RLS development and can inhibit R. collo-cygni epidemics.

- Ramularia leaf spot

- fungicide target proteins

- CYP51

- azoles

- SDHI

- mlo gene

1. Introduction

Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) is one of the most important cereal crops grown in temperate regions worldwide [1]. Among the various pests and diseases that threaten sustainable barley cultivation [2], Ramularia leaf spot (RLS)—caused by an ascomycete, Ramularia collo-cygni—has become a new threat to barley cultivation. The first reported case of the disease dates back to 1893 in northern Italy and was identified by a notable botanist, Fridiano Cavara. For a century, RLS was a minor disease and did not cause any serious problems in barley cultivation, but the majority of R. collo-cygni outbreaks have been reported in the last few decades. The first official records in Germany, the UK, Ireland, and New Zealand are from the 1990s. In Finland, Sweden, Denmark, and France, the first records are from the 2000s, and in Estonia, Spain, and Australia, the first records are after 2010 [3]. Since the beginning of 2000, RLS has been considered to be an emerging disease of barley in Europe, South America, and New Zealand [2,4,5]. It is possible that RLS can lead to moderate barley yield losses of 5–20% or greater. Although the trigger of these increasing RLS epidemics is still under debate, R. collo-cygni adaptation to widely distributed RLS-susceptible barley cultivars and fungicides along with heat stress under global climate change will lead to a risk of future RLS epidemics [3,6].

2. Epidemiology of Ramularia collo-cygni

It has been speculated that the seed-borne stage in the life cycle of R. collo-cygni is the most common means of the pathogen’s worldwide distribution [7]. In the infected seed, the pathogen hides in the lemma, pericarp, and embryo [7]. The global trade of barley seeds might be one of the main reasons this pathogen has spread worldwide. The control of the pathogen by chemical seed treatment has been examined but, to date, without success [8]. In addition to barley seeds, volunteers, crop debris, and other grasses may contribute to the pathogen’s survival and local sources of inoculum [9].

Air-borne asexual spores and sexual ascospores of R. collo-cygni disperse during the growing season and infect susceptible hosts [10,11]. The pathogen infects the seeds during plant growth, and with no external inoculum, it colonizes the emerging leaf layers [11]. The endophytic phase of R. collo-cygni without any visual disease symptoms continues until it undergoes developmental changes transforming it into a detrimental necrotrophic pathogen; these changes may be triggered by numerous factors (e.g., a nutrient deficiency, changes in the levels of reactive oxygen species in host tissues, and plant senescence) [9,12,13]. Furthermore, the production of several virulence factors by R. collo-cygni during leaf infection is probably involved in the development of the symptoms of RLS disease [14]. The visual symptoms of RLS often develop in diseased plants after ear emergence, although, in conducive environmental conditions, symptoms can be detected even sooner [5,15].

It is still poorly understood why R. collo-cygni became an aggressive pathogen in most European countries at the beginning of the 2000s. Many factors, as well as the lack of RLS-resistant cultivars, reduced fungicide efficacy, and climate change, could have affected the disease’s occurrence and development. Barley breeding has concentrated on introducing genes conferring resistance to intensive powdery mildew attacks into new cultivars; today, cultivars carrying the mlo-11 mutation are widely used to provide plants with durable resistance to powdery mildew infections (as reviewed by Brown and Rant [16]). Unfortunately, mlo-11-mutation cultivars are more susceptible to several non-biotrophic diseases including RLS [17]. The plant’s genetic resistance to RLS remains unknown. In addition, as a consequence of the intensive use of fungicides in the past, several fungicides have reduced efficacy in barley disease control, and the crop is therefore unprotected against R. collo-cygni attack. The exposure to fungicides may have led to an imbalanced soil and plant-related microbial community as well as a reduction in microorganisms antagonistic to R. collo-cygni.

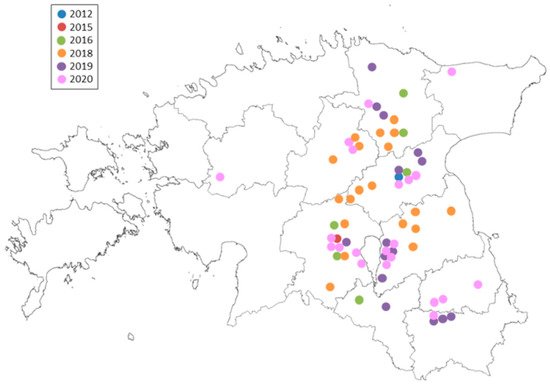

In the Baltic countries, RLS was first diagnosed in Lithuania in 2004 [18]. In 2012, the first few attacks of RLS were only identified in Jõgeva county near the Estonian Crop Research Institute [19]. Field monitoring from 2015 to 2020 showed that R. collo-cygni had rapidly spread to the majority of barley-cropping areas (Figure 1). Due to the increasing spread of R. collo-cygni, RLS has become a newly emerging disease in Estonian barley fields. The control strategies for barley protection mainly rely on DMI- and SDHI-class fungicides—for instance, commercial pesticide products such as Input (Bayer AG, Leverkusen, Germany; a.i. prothioconazole 160 g/L, spiroxamine 300 g/L), Tango Super (BASF, Ludwigshafen, Germany; a.i. epoxiconazole 84 g/L, fenpropimorph 250 g/L), Viverda (BASF, Ludwigshafen, Germany; a.i. boscalid 140 g/L, pyraclostrobin 60 g/L, epoxiconazole 50 g/L), and Priaxor (BASF, Ludwigshafen, Germany; a.i. fluxapyroxad 75 g/L, pyraclostrobin 150 g/L). This has led to the accumulation of resistance mutations in the target proteins’ genes and increased the fungicide-resistant population [20]. We also cannot exclude the fact that several popular barley cultivars (e.g., ‘Soldo’, ‘Montoya’, ‘Katniss’, and ‘KWS Irina’) grown in Estonia carry the mlo-11 mutation in the genome. Consequently, similar factors have favored the spread of R. collo-cygni in Estonia as well as in other European countries.

Figure 1. Ramularia collo-cygni spread and detection in 2012–2020 in Estonia.

R. collo-cygni populations across Europe frequently recombine and are highly diverse, which enables them to be adaptive to different environmental conditions [21,22]. Genetic studies have shown highly admixed R. collo-cygni populations without geographical clustering, which emphasizes the significance of the global seed market and delivery in spreading the pathogen genotypes and accelerating the spread of fungicide resistance [22]. It is challenging to assume the presence and spread of the pathogen because, in the endophytic phase, RLS symptoms are not present. Typical symptoms occur in the late growing season and often lead to the mistaken diagnosis of other diseases and physiological leaf spots [23].

3. Fungicide Resistance in R. collo-cygni Populations

Fungicides are commonly used in crop protection for yield benefits in Europe, especially in countries such as Great Britain and Ireland with high humidity favorable for pathogen epidemics in the growing season [24]. R. collo-cygni presents a substantial risk of acquiring resistance to fungicides applied to barley fields [25]. R. collo-cygni in several European countries (e.g., the UK, France, Denmark, and Estonia) has already developed resistance to quinone-outside inhibitors (QoIs; FRAC Code 11), a single-site-inhibiting fungicide class that previously showed high efficacy [20,26,27]. Recently, disease control has been accomplished using two single-site fungicide classes, the succinate dehydrogenase inhibitors (SDHIs; FRAC Code 7) and the demethylation inhibitors (DMIs; FRAC Code 3), as well as the multi-site inhibitor chlorothalonil (FRAC Code M 05) [4]. Despite the high efficacy of chlorothalonil in RLS control [28], chlorothalonil-based fungicides were forbidden by the European Food Safety Association (EFSA) from 2020 onwards because of serious environmental safety concerns and a high risk to amphibians and fish [29]. The European regulation 128/2009 managing the use of pesticides has recently withdrawn various fungicides from the market because of environmental and health-related concerns. These changes will inevitably lead to adjustments in future resistance-breeding strategies to produce an increased number of abiotic- and biotic-stress-tolerant barley cultivars and focus on effective integrated pest-management strategies.

3.1. Status of DMI-Fungicide Sensitivity

DMIs have been beneficial for maintaining the health of crops and achieving higher yields from the fields. However, the wide use of DMIs for more than three decades has led to the emergence of adapted strains of cereal pathogens and a reduction in the efficacy of the active ingredients of fungicides [24,30,31]. The most relevant mechanism for DMI-resistant adaptations in numerous fungal pathogens is mutations in the coding region of CYP51 [32,33]. In total, 12 different alterations and 15 different R. collo-cygni CYP51 haplotypes were identified based on the mutation combinations in 2017 in Europe [34]. The most frequent haplotype was C1, with the mutations I381T, I384L, and Y459C in CYP51, and the second-most-common haplotype, C3, had a combination of I381T, I384L, and Y461H mutations [34]. These haplotypes are spreading, which results in a lower field efficacy for DMI fungicides [34]. In eastern Europe—for instance, Estonia—the development of fungicide resistance has been slower [20]. However, two mutations—I381T and I384T—were simultaneously present in the same R. collo-cygni isolates in 93–96% of the isolates, and mutation combinations similar to haplotype C1 occurred in 70–80% of the isolates recently collected in Estonia [20]. Unfortunately, the CYP51 gene’s evolution and additional resistance mechanisms (e.g., the combination of gene mutations with promoter insertions or an enhanced efflux) in R. collo-cygni are yet unknown.

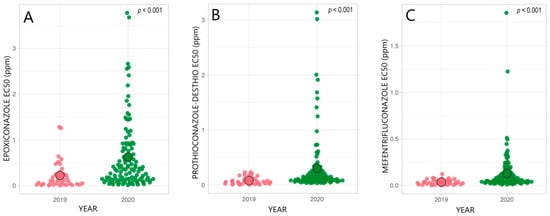

We observed a significant shift and wider distribution in the EC50 values of epoxiconazole (EPX), prothioconazole-desthio (PTZ-D), and mefentrifluconazole (MEF) in 2020 compared with 2019 in the Estonian R. collo-cygni population, as illustrated in Figure 2 [20]. In the Estonian R. collo-cygni population, a remarkable number of isolates had higher EC50 values (>1.0 ppm) for EPX and PTZ-D in 2020 compared with 2019 [20]. The selection pressure for DMI-class fungicides in Estonia was lower than that in Western Europe, and fungicide resistance has developed more slowly in the pathogen population. The climatic conditions in Estonia are also less favorable for RLS, and chemical control is, therefore, less intensively used. In countries with more severe or numerous RLS epidemics (e.g., the UK, Germany, and Austria), the chemical control of the disease is a common practice and, since 2015, R. collo-cygni populations have significantly lost sensitivity to DMI fungicides [35].

Figure 2. Distribution of the azole sensitivity of the R. collo-cygni population in 2019 and 2020 in Estonia. Epoxiconazole (A); prothioconazole-desthio (B), and mefentrifluconazole (C) were tested. ○ indicates the average EC50 value (ppm) in a population; p < 0.001 shows a significant difference between the years [20].

Several research groups have shown that DMI fungicides, e.g., MEF and tebuconazole (TEB), encounter cross-resistance in the wheat pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici population; farmers should be careful with extensive applications of TEB for cereal-plant protection [36,37]. A high positive correlation between PTZ-D and MEF sensitivity was noticed in the R. collo-cygni population [20]. EPX sensitivity was significantly correlated with PTZ-D and MEF sensitivity [20].

3.2. Status of SDHI-Fungicide Sensitivity

SDHI fungicides have been highly efficient, and the emergence of resistance to SDHIs in the field has been rare. Several mutations in the SdhB (B-H266Y/R, B-T267I, and B-I268V) and SdhC subunits (C-N87S, C-H146R, and C-H153R) of the SDH enzyme in R. collo-cygni can be observed [34]. The future of SDHIs’ field performance could be threatened as various studies have shown that laboratory mutants, as well as SDHI-insensitive isolates in Europe, have increased since 2014 [34,38]. Increased resistance to SDHIs in other widespread cereal pathogens, Pyrenophora teres [39] and Z. tritici [40,41], highlights the negative outcomes and high risk of SDHI-resistance evolution.

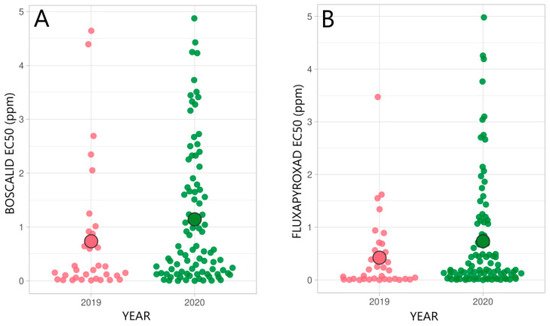

Recently, the mutations C-H146R and C-H153R in the SdhC subunit, which confer a noticeable reduction in SDHI sensitivity, and C-N87S, which reduces sensitivity, were identified in R. collo-cygni isolates collected from Germany, France, Austria, UK, and Ireland from 2014 to 2017 [34,35]. Although during the last decade SDHI-class fungicides have often been applied for crop protection in Estonia, mutations have only occurred in the SdhC subunit [20]. The prevailing mutation C-H146R in the SdhC subunit, which significantly increases the resistance factor, was detected in 55–63% of the R. collo-cygni isolates in recent years in Estonia [20]. Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of the SDHI-fungicide sensitivity of Estonian R. collo-cygni in 2019 and 2020, with highly variable EC50 values ranging from 0 to 5 ppm, as determined in a microtiter plate assay [20].

Figure 3. Distributions of the SDHI-fungicide sensitivity of R. collo-cygni to boscalid (A) and fluxapyroxad (B) in 2019 and 2020 in Estonia. ○ shows the average EC50 value (ppm) in a population [20].

4. Common Barley Cultivars Enhance RLS Epidemics

One possibility for reducing the fungicide input in plant protection is to breed and cultivate sustainable barley cultivars with multiple sources of host-plant resistance. Breeding new cultivars with greater disease resistance has had a significant impact on the epidemiology of plant diseases. None of the current common cultivars have full resistance to RLS.

The mlo gene in the barley genome is agronomically highly significant because it is involved in the development of barley’s resistance to the powdery mildew pathogen Blumeria graminis f. sp. hordei [42]. The powdery-mildew-resistance gene, mlo-11, was identified in 1942 in an Ethiopian barley line, Grannenlose Zweizeilige. All the known mlo alleles are non-functional [43]. However, conventional plant breeding is time-consuming and the first powdery-mildew-resistant cultivar with the mlo-11 allele was ready for cultivation in 1979 [44]. After the release of the barley cultivar Atem, the interest in the mlo cultivars rapidly increased and the success of cultivars with the mlo mutant allele has continued. Around 70% of the European spring barley cultivars have the mlo mutant allele in the genome [45].

5. Pleiotropic Effect of mlo Alleles on RLS

Unfortunately, the mutant mlo alleles introduced into barley cultivars can have deleterious agronomic effects, including a reduced yield [46] and a higher susceptibility to facultative pathogens including R. collo-cygni [17]. The development of RLS as an emerging new disease of spring barley in many regions may be influenced by the widespread use of mlo alleles (particularly mlo-11) in plant breeding and the exploitation of these cultivars. RLS symptoms typically appear as the crop senesces, with a reduction in the activity of the host’s antioxidant system, implying that the progress of RLS may be connected to host stress [13,47]. The effect of mlo alleles on RLS may be related to a complex rearrangement of the physiological processes in leaves, the ROS levels, or both, according to the research of Oxley and Havis [48]. Genes that regulate cell death in barley (e.g., nec and ror) interact with the negative cell-death regulator MLO, which affects plant-disease development and pathogens (such as R. collo-cygni) [17,49,50]. Rapid leaf senescence in mlo cultivars may induce a faster transformation of R. collo-cygni from an endophytic to a necrotrophic lifestyle, which could be increased further by external factors that promote oxidative stress in the plant [51,52]. Drought-tolerant transgenic barley plants that overexpressed stressed-related NAC1 (SNAC1) had delayed senescence and showed greater resilience to abiotic stressors and RLS infection [51]. If abiotic-stress factors induce fungal development from an endophyte to a necrotrophic pathogen, then plants with a greater tolerance to abiotic stress also have greater protection against disease development.

6. Future Challenges

Under the current climate change trajectory, RLS epidemics are predicted to increase [5]. For sustainability and high yields in barley production, the crop needs to be protected as effectively as possible according to the best scientific knowledge and experimental data. Therefore, fungicides to which the pathogen is sensitive are preferable for use in disease-control strategies. Combining and rotating fungicides with different modes of action may also help. A high dose may be required under an elevated disease pressure, particularly for susceptible cultivars or where the sensitivity has been reduced and the dose has to be increased to maintain effective control. Unfortunately, in most cases, high fungicide doses accelerate the development of fungicide resistance in the pathogen population [53].

Barley is an important food and feed crop around the world, and the cultivars grown should be able to adapt to different growing conditions and geographical areas. Under increasing RLS pressure, the mechanisms of RLS infection and the pathogen’s epidemiology require further research, and barley cultivars need to be less adversely affected by plant pathogens. To combat the challenges of future food security, plant-breeding strategies and methods should be innovative and rapid. As the plant-defense mechanisms providing cross-resistance to different fungal pathogens are still not understood in detail, the widespread use of a few single resistance alleles in plant breeding will not necessarily be beneficial. This practice may have contrasting effects on the plant-disease epidemiology, decreasing the fitness of one pathogen and increasing that of another.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!