Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Cell & Tissue Engineering

The process of full-thickness skin regeneration is complex and has many parameters involved, which makes it difficult to use a single dressing to meet the various requirements of the complete regeneration at the same time. Therefore, developing hydrogel dressings with multifunction, including tunable rheological properties and aperture, hemostatic, antibacterial and super cytocompatibility, is a desirable candidate in wound healing.

- hydrogel dressing

- full-thickness skin regeneration

- 3D cell culture

1. Introduction

In the human body, the skin is the most extensive and most vulnerable tissue. Skin also plays a significant role in defending external damage and microbial infection [1]. Once the skin tissue is damaged, the cutaneous wound healing might be a complex multi-step process that involves related dermal and epidermal events. During the skin repairing process, lots of soluble factors, blood elements, extracellular matrix (ECM) and cells were involved [2]. The skin repair may generally be divided into four continuous phases: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation and remodeling [3]. Although most incisional skin wounds can be effectively healed, excisional wounds, also called the extensive full-thickness wound usually hard to repair, causing severe infecting and thus threatening life. Thus, the design of wound dressings with multifunctional properties is highly desired.

The functions of wound dressings may include but are not limited to covering the wound and acting as a temporary barrier, guiding the reorganization of skin cells and re-integration of host wound skin tissues, including epidermis, basement membrane and dermis. An ideal skin wound dressing should meet the requirements below: sufficient mechanical strength, good moisture retention, appropriate surface microstructure, excellent tissue compatibility [4]. A variety of biomedical materials can be served as wound dressings, such as fibrous [5] membranes [6], polymer and polysaccharide scaffolds [7], nanoparticles [8], and hydrogels [9]. Compared with other dressing materials, hydrogels dressings [10][11] are attracting increasing attention due to their adjustable physicochemical properties, similar to ECM, able to modulate the fluid balance and accelerate wound repair [12][13]. Several hydrogel dressings with remarkable antibacterial activity and excellent promotion to wound healing [14][15]. Thus, developing a multifunctional hybrid hydrogel dressing to promote the full-thickness wound healing process is highly desirable.

Chitosan (CS) [16][17] and alginates (SA) [18][19], as natural polysaccharides, have received increasing attention due to their high hydrophilicity and outstanding biocompatibility. CS [20][21], as the unique cationic polysaccharide, shows high antimicrobial activity due to the interaction between positively charged CS and the negatively charged bacterial membrane [22]. Among these materials, CS may be considered as an ideal candidate in the wound repair stages of inflammation [23]. Besides, due to the outstanding biocompatibility, suitable biodegradability and low toxicity, CS has become one of the most extensively used hydrogel dressings [24]. In addition, CS can induce local macrophage proliferation, stimulate the remodeling of ECM and thus promote early wound healing. Furthermore, CS processes abundant primary amine groups, which endows them to react with carboxyl groups [25][26][27]. SA, a natural anionic polysaccharide (carboxyl groups), is of particular interest for skin dressings due to their non-toxic and biocompatibility [28]. Concerning their chemical formula and structure, SA own ease of gelation kinetics and similarity to natural ECM [29], which makes them proper candidates compared to other biomaterials. Although SA lacks an adhesive motif that can initiate cell adhesion, the addition of growth factors may help improve the cell adhesion.

Growth factors belonging to the fibroblast growth factors (FGF) family play crucial roles in tissue repair and regeneration. The FGF family are small proteins and process a typical β-barrel structure as the core [30]. The FGF can be divided into three major groups: canonical, hormone-like, and intracellular. The FGF plays a vitally important role in tissue repair processes after mechanical injury, burns and chemical damage [31]. In general, the function of FGF includes stimulating cell proliferation and migration [32]. FGF could also enhancing angiogenesis which promote the formation of new vessels from pre-existing vessels [33][34]. FGFs can regulate many aspects of the cell phenotype, which is critical to tissue repair. For example, for endothelial cells, FGF2 could promote lifespan extension and angiogenesis, suppress apoptosis [35]. For fibroblasts, FGF2 could suppress their differentiation to myofibroblasts. Vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin) is an endothelial-specific marker expressed by endothelial cells during vasculogenesis [36] and a major component of endothelial adherens junctions. VE-cadherin is crucial for the organization of the newborn vascular network [37]. Besides, the function of VE-cadherin also includes promoting endothelial differentiation and mediating the interstitial mechanotransduction [38].

2. Physical Characterization of Complex Hydrogels

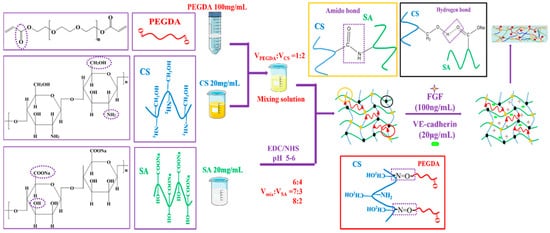

The structural formula and schematic drawing of the CS/SA/PEGDA complex hydrogels are showed in Figure 1. The volume ratio of mixing solution and SA were 6:4, 7:3, 8:2, and were named C6-S4, C7-S3, C8-S2, respectively. After that, VE-cadherin (20 μg/mL) and FGF (100 ng/mL) were added to the C8-S2 hydrogel and signed as C8-S2-V and C8-S2-F, respectively. The hydrogel added to the VE-cadherin (20 μg/mL) and FGF (100 ng/mL) at the same time were signed as C8-S2-F-V.

Figure 1. The structural formula of PEGDA, CS, SA and the schematic drawing of complex hydrogels.

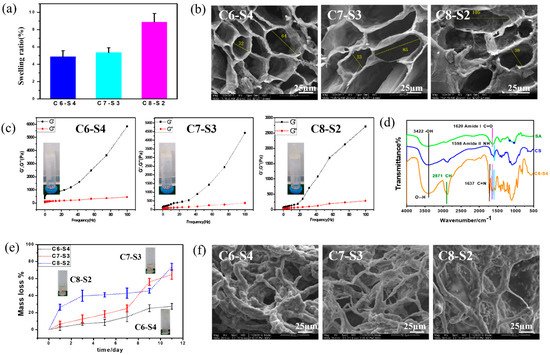

The complex hydrogels were semi-transparent and non-flowing condition. The proper water uptake ability of hydrogel helps to accelerate the process of wound healing through absorbing exudate from wounds and reducing the risk of infection, which was one of the requirements for wound dressings. Swelling tests were used to determine the swelling ratio (SR) of the complex hydrogels, which were analyzed by the weight ratio of dried state (Wd) and fully swollen state (Ws). The equilibrium mass swelling of complex hydrogel was calculated according to the formula: SR = (Ws − Wd)/Wd. As showed in Figure 2a, the swelling ratio of C6-S4, C7-S3 and C8-S2 hydrogels were 4.87, 5.32 and 8.86, respectively. The equilibrium mass swelling of hydrogel increases with the increase of the amount of chitosan in the hydrogel.

Figure 2. Physical characterization of complex hydrogels. (a) The swelling ratio of complex hydrogels (mean ± SD, n ≥ 3). (b) SEM micrograph of complex hydrogels. The scale bar stands for 25 µm in (b). (c) Rheological behavior of complex hydrogels, in which the forming state of com- plex hydrogels were showed in the left of each picture. (d) The FTIR of alginate (SA), chi-tosan (CS) and C6-S4 hydrogel. (e) The mass loss of complex hydrogels within 11 days of degra-dation. (f) SEM micrograph of complex hydrogels after 11 days of degradation. The scale bar stands for 25 µm in (f).

Figure 2b results showed scanning electron microscope (SEM) micrographs of the cross section of the complex hydrogels. The pores present elliptical shapes, and the pore size changed with the different proportions of hydrogels. In general, with the increase of chitosan content, the major axis of elliptical shapes increased. According to the calculation, C6-S4 showed the smallest pore size (about 32 μm for minor axis and 64 μm for major axis), and C8-S2 showed the largest pore size (about 38 μm for minor axis and 105 μm for major axis). Pore size at dozens of micrometers is beneficial to the transportation of nutrients and convenient for the ingrowth of cells. The different aperture sizes were mainly due to the different crosslinking degrees of the hydrogel, which suggested the crosslinking degree decreased with the increase of chitosan content.

To analyze the influence of different chitosan content on the rheological properties of the complex hydrogels, the curves of storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) of the hydrogels over frequency were recorded. The G′ of C6-S4 hydrogel (5848 Pa) was higher than C7-S3 (4428 Pa) hydrogel and C8-S2 (2778 Pa) hydrogel at 100 Hz. The rheological properties showed the same rule at low frequency. The G′ of C6-S4 hydrogel (764 Pa) was higher than C7-S3 (302 Pa) hydrogel and C8-S2 (211 Pa) hydrogel at 10 Hz. This is because more chitosan content in the hydrogel decreased the crosslinking density and thus leading to the lower G′ of the hydrogel (Figure 2c).

The fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) of alginate (SA), chitosan (CS) and C6-S4 hydrogel were showed in Figure 2d. The characteristic peak of hydrogen bond may be found at 3422 cm−1, The characteristic peak of amido bond and carbon and oxygen double bond may be found at 1598 cm−1 and 1620 cm−1, respectively. The characteristic peak of carbon and nitrogen double bond may be found at 1637 cm−1.

After immersing in PBS for 11 days, the hydrogels condition was taken photos (Figure 2e). For the C6-S4 sample, the hydrogel was almost complete and maintained a non-flowing state. In contrast, for C7-S3 and C8-S2 samples, the hydrogel resolved in PBS with large pieces of gels and represented a flowing state. Degradation tests were used to determine the Degradation ratio (DR) of the complex hydrogels. Firstly, the complex hydrogels were immersed in 0.01 M PBS at 37 °C with shaking at 70 rpm until the weight of all hydrogels was kept constant and the weight were denoted as W0. At the predetermined time, the hydrogels were taken out, rinsed using RO water to remove excess salinity, the superficial water of gels were removed by filter paper, and the weight was denoted as W′. DR of hydrogels was analyzed by the formula: DR = (W0 − W′)/W0 × 100%. According to the calculation, for C6-S4, C7-S3 and C8-S2 hydrogel, the mass loss was 15.18%, 24.99% and 42.81% after degradation for 5 days, respectively. Similarly, for C6-S4, C7-S3 and C8-S2 hydrogel, the mass loss was 27.40%, 64.88% and 73.73% after degradation for 11 days, respectively (Figure 2e).

Figure 2f showed SEM micrographs of the cross section of the complex hydrogels after degradation for 11 days. Compared to the SEM micrographs before and after degradation, the pore size became larger, and communicating pores appeared. In general, after degradation for11 days, these hydrogels still maintained hydrogel condition and processed certain crosslinking degrees. According to the SEM, with the increase of chitosan content, the pore size of the hydrogel increased and the connection between holes thinner.

3. Hemolysis and Whole Blood Dynamic Coagulation Evaluation Results

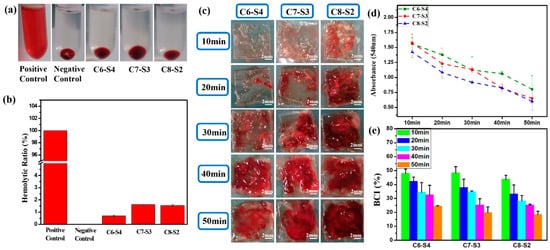

As showed in Figure 3a, the supernatant is transparent and without apparent hemolysis. Furthermore, the hemolysis ratio of all the hydrogels were less than 5% (Figure 3b), which accorded with the standard of blood contacted material. When the blood is connected to the hydrogels, the connection may lead to the rupture of red blood cells and cause hemolysis. Therefore, the hemolysis test is an essential experiment for the safety of blood connected materials.

Figure 3. Blood compatibility evaluation of complex hydrogels. (a) The photos of complex hydrogels). (b) The hemolytic ratio of complex hydrogels. (mean ± SD, n ≥ 3). (c) The photos of whole blood assay of complex hydrogels at different times. The scale bar stands for 2mm in (c). (d) The whole blood assay absorbance of complex hydrogels at different times. (mean ± SD, n ≥ 3). (e) The BCI of complex hydrogels at different times (mean ± SD, n ≥ 3).

The whole blood dynamic coagulation assay was carried out to detect the coagulation after the blood was connected to the hydrogels. After the hydrogel was connected to the blood for 10, 20, 30, 40 and 50 min, the blood clots that coagulated on hydrogels were showed in Figure 3c. For C6-S4 hydrogels, there were hardly any blood clots within 20 min, only a tiny amount of blood clots was formed during 20–30 min, and mass of blood clots began to form after 30 min. These results implied that the formation of large blood clots was postponed to 30 min after the hydrogel connected to the blood for C6-S4. In contrast, for C8-S2 hydrogel, there were few blood clots after the hydrogel connected to the blood for 10 min. After that, more and more blood clots began to form, which means the significant coagulation reaction occurred after 10 min connection. Figure 3d showed the absorbance of hydrogels at different point times. As time went by, more and more blood involved in the coagulation reaction; the uncoagulated blood became less and led to a lower absorbance. Therefore, the lower the absorbance, the better the coagulation effect. The blood coagulant index (BCI) of hydrogels were analyzed by the following formula: As/Aw × 100%. After the connection of 10 min, the BCI of all hydrogels were above 40%, which exhibited soft coagulation and prevented the blockage of capillaries (Figure 3e). Ten minutes later, the C8-S2 hydrogels began to form blood clots to prevent the hemorrhage of large vessels.

4. Antibacterial Activity Assessment

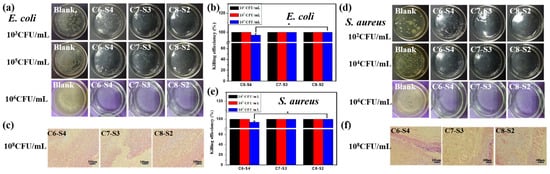

The antibacterial activities of complex hydrogels against Gram-negative bacteria E. coli and Gram-positive bacteria S. aureus were conducted by surface antibacterial assay, and LB agar gel plates without hydrogels were set as control and marked as blank. After incubation at 37 °C for 12 h, the hydrogel plates and agar gel plates were taken photos to observe the colony-forming units (CFUs) on each plate. There were no CFUs on every plate (Figure 4a,d). Then, in order to detect the bacteria on each plate, 1 mL sterilized PBS was added to each hydrogel plate to dissolve survived bacteria and then the suspension was spaced on the agar gel surfaces and incubated. The killing efficiency was calculated using the following formula: (N1 − N2)/N1 × 100%, where N1 refers to the number of CFUs of control, and N2 refers to the number of CFUs of the survive to count on complex hydrogels. At the bacterial concentrations of 103 and 105 CFU/mL, the CFUs were not found on the complex hydrogels, and a large amount of CFUs appeared on the control plate (agar gel), exhibiting 100% killing efficiency against E. coli. At the bacterial concentrations of 102 and 104 CFU/mL, the CFUs were not found on the complex hydrogels, and a large amount of CFUs appeared on the agar gels, exhibiting 100% killing efficiency against S. aureus. When the bacterial concentration was increased to 106 CFU/mL, the hydrogels also exhibited high killing efficiency against both microorganisms. The killing efficiency of C6-S4, C7-S3 and, C8-S2 hydrogel against E. coli was up to 97.1%, 100% and 100%, respectively (Figure 4b). Similarly, the killing efficiency of C6-S4, C7-S3 and, C8-S2 hydrogel against S. aureus were up to 96.5%, 100% and 100%, respectively (Figure 4e). The process of wound healing may be delayed or cause infection due to bacterial infection. Therefore, the antibacterial assessment aiming to detect the antibacterial ability of hydrogel as wound dressings are of vital importance. So, as an ideal wound dressing, the antibacterial ability should become their inherent property which could reduce the complications and accelerate the healing process of the wound site.

Figure 4. Antibacterial activity evaluation of complex hydrogels. (a) Bacteriostatic pictures of complex hydrogels for E. coli under the 103 CFU/mL, 105 CFU/mL and 106 CFU/mL bacterial. (b) The killing efficiency of hydrogels against E. coli. (mean ± SD, n ≥ 3, * p < 0.05). (c) Gram stain pictures of complex hydrogels after animals affected with 108 CFU/mL E. coli for 24 h. The scale bar stands for 100 µm in (c). (d) Bacteriostatic pictures of complex hydrogels for S. aureus under the 102 CFU/mL, 104 CFU/mL and 106 CFU/mL bacterial concentration. (e) The killing efficiency of hydrogels against S. aureus. (mean ± SD, n ≥ 3, * p < 0.05). (f) Gram stain pictures of complex hydrogels after animals affected with 108 CFU/mL S. aureus for 24 h. The scale bar stands for 100 µm in (f).

The in vivo antibacterial activities of complex hydrogels against E. coli and S. aureus were evaluated via rats’ full-thickness infected skin defect model. After adding the bacterial suspension to the defected skin for 30 min, hydrogel dressing was covered to the defected skin for 24 h, and the wound tissues were harvested and stained by the gram. The tissue containing E. coli could appear red pattern, the tissue containing S.aureus could appear bluish violet pattern, and the healthy tissue could appear pink pattern. The more red or bluish violet patterns, the more E. coli or S. aureus bacteria. For E. coli groups, no red pattern appeared on all the hydrogel groups, suggesting the excellent antibacterial property against E. coli (Figure 4c). For S. aureus groups, there were little bluish violet patterns on the C6-S4 hydrogel group, and there were scarcely any bluish violet patterns on the C8-S2 hydrogel group (Figure 4f). Therefore, C8-S2 hydrogel showed better antibacterial properties than the C6-S4 hydrogel group against S. aureus.

5. Three-Dimensional Encapsulation of Cells in Complex Hydrogels

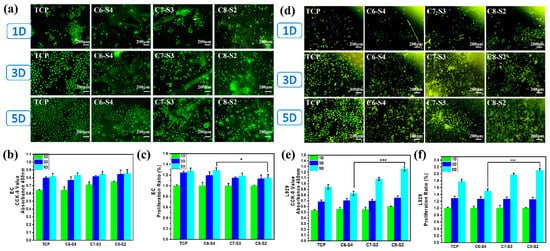

To further evaluate the cytocompatibility of hydrogels, the L929 cells and ECs were encapsulated into the hydrogels. The morphology of adherent cells was stained by rhodamine 123, and the number of cells was detected by CCK-8 assay. As showed in Figure 5a, the morphology of endothelial cells on a tissue culture plate (TCP) showed a typical cobblestone shape morphology. However, the morphology of endothelial cells on hydrogels (C6-S4, C7-S3 and C8-S2) showed a spheroidal morphology and un-spread state (Figure 5a). In terms of cell viability, all the hydrogel groups showed no apparent difference within five days (Figure 5b). However, in terms of the proliferation of cells, the C8-S2 hydrogel revealed better proliferation than the C6-S4 hydrogel (Figure 5c). The morphology of L929 in hydrogels was also analogous with the EC, which exhibited spherical and non-spread shape (Figure 5d). For the culture of L929, the C8-S2 hydrogel exhibited a significant difference with the C6-S4 hydrogel in the aspects of cell viability and proliferation (Figure 5e,f), indicating the promoting effect of chitosan on cell proliferation.

Figure 5. Evaluation of cells compatibility. (a) EC morphology of complex hydrogels. The scale bar stands for 200 µm in (a). (b) The CCK-8 results of EC. (mean ± SD, n ≥ 3, * p < 0.05). (c) The proliferation ratio of EC. (mean ± SD, n ≥ 3, * p < 0.05). (d) L929 morphology of complex hydrogels. The scale bar stands for 200 µm in (d). (e) The CCK-8 results of L929. (mean ± SD, n ≥ 3, *** p < 0.01). (f) The proliferation ratio of l929. (mean ± SD, n ≥ 3, *** p < 0.01).

6. Three-Dimensional Encapsulation of Two Factors and Two Cells in Complex Hydrogels

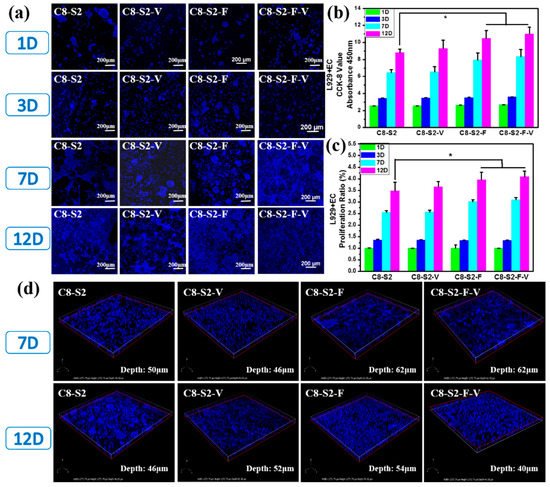

To further evaluate the cytocompatibility of these hydrogels, the co-culture of L929 and EC with the incorporation of FGF and VE-cadherin were carried out. As showed in Figure 6a, there were only a few cells on all the hydrogel samples within three days. The cell viability of all hydrogel groups on the 1st and 3rd days showed no noticeable difference (Figure 6b). However, the number of cells on the 7th day significantly increased compared to the 3rd day, demonstrating that the cells grew well and were in a state of proliferation. After 12 days’ co-incubation, C8-S2-F and C8-S2-F-V hydrogels exhibited higher cell number and better cell proliferation than other hydrogels, indicated the promoting effect of FGF on cells proliferation (Figure 6c). The above experiments confirmed the brilliant cytocompatibility on the co-culture of L929 and EC. Generally speaking, cells tend to form multicellular spheroids (Figure 6d). At the same time, the transportation of oxygen and nutrients to the core may be difficult when the spheroids grow. Therefore, the spheroids’ diameter is limited to 200–400 μm [39].

Figure 6. Evaluation of L929&EC co-culture compatibility. (a) Morphology of L929&EC of complex hydrogels. The scale bar stands for 200 µm in (a). (b) the CCK-8 results of L929&EC; (c) the proliferation ratio of L929&EC. (mean ± SD, n ≥ 3, * p < 0.05); (d) the 3D morphology of L929&EC and the complex hydrogels.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms23031249

References

- Du, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Yan, H.; Wang, L.; Qu, L.; Kong, D.; Qiao, M.; Wang, L. Injectable hydrogel composed of hydrophobically modified chitosan/oxidized-dextran for wound healing. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2019, 104, 109930.

- Rousselle, P.; Montmasson, M.; Garnier, C. Extracellular matrix contribution to skin wound re-epithelialization. Matrix Biol. 2019, 75–76, 12–26.

- Liang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Hu, T.; Chen, B.; Yin, Z.; Ma, P.X.; Guo, B. Adhesive Hemostatic Conducting Injectable Composite Hydrogels with Sustained Drug Release and Photothermal Antibacterial Activity to Promote Full-Thickness Skin Regeneration During Wound Healing. Small 2019, 15, e1900046.

- Liang, Y.; He, J.; Guo, B. Functional Hydrogels as Wound Dressing to Enhance Wound Healing. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 12687–12722.

- Zare-Gachi, M.; Daemi, H.; Mohammadi, J.; Baei, P.; Bazgir, F.; Hosseini-Salekdeh, S.; Baharvand, H. Improving anti-hemolytic, antibacterial and wound healing properties of alginate fibrous wound dressings by exchanging counter-cation for infected full-thickness skin wounds. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2020, 107, 110321.

- Bakhsheshi-Rad, H.R.; Hadisi, Z.; Ismail, A.F.; Aziz, M.; Akbari, M.; Berto, F.; Chen, X.B. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of chitosan-alginate/gentamicin wound dressing nanofibrous with high antibacterial performance. Polym. Test. 2020, 82, 106298.

- Guerle-Cavero, R.; Lleal-Fontas, B.; Balfagon-Costa, A. Creation of Ionically Crosslinked Tri-Layered Chitosan Membranes to Simulate Different Human Skin Properties. Materials 2021, 14, 1807.

- Chen, K.; Wang, F.; Liu, S.; Wu, X.; Xu, L.; Zhang, D. In situ reduction of silver nanoparticles by sodium alginate to obtain silver-loaded composite wound dressing with enhanced mechanical and antimicrobial property. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 148, 501–509.

- Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.R.; Xia, S.; Gao, G.H. An environment-stable hydrogel with skin-matchable performance for human-machine interface. Sci. China Mater. 2021, 64, 2313–2324.

- Yazdi, M.K.; Vatanpour, V.; Taghizadeh, A.; Taghizadeh, M.; Ganjali, M.R.; Munir, M.T.; Habibzadeh, S.; Saeb, M.R.; Ghaedi, M. Hydrogel membranes: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2020, 114, 111023.

- Cascone, S.; Lamberti, G. Hydrogel-based commercial products for biomedical applications: A review. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 573, 118803.

- Mohamad, N.; Loh, E.Y.X.; Fauzi, M.B.; Ng, M.H.; Mohd Amin, M.C.I. In vivo evaluation of bacterial cellulose/acrylic acid wound dressing hydrogel containing keratinocytes and fibroblasts for burn wounds. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2019, 9, 444–452.

- Liang, Y.; Chen, B.; Li, M.; He, J.; Yin, Z.; Guo, B. Injectable Antimicrobial Conductive Hydrogels for Wound Disinfection and Infectious Wound Healing. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 1841–1852.

- Yu, Y.; Yuk, H.; Parada, G.A.; Wu, Y.; Liu, X.; Nabzdyk, C.S.; Youcef-Toumi, K.; Zang, J.; Zhao, X. Multifunctional “Hydrogel Skins” on Diverse Polymers with Arbitrary Shapes. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1807101.

- Qianqian, O.; Songzhi, K.; Yongmei, H.; Xianghong, J.; Sidong, L.; Puwang, L.; Hui, L. Preparation of nano-hydroxyapatite/chitosan/tilapia skin peptides hydrogels and its burn wound treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 181, 369–377.

- Furlani, F.; Rossi, A.; Grimaudo, M.A.; Bassi, G.; Giusto, E.; Molinari, F.; Lista, F.; Montesi, M.; Panseri, S. Controlled Liposome Delivery from Chitosan-Based Thermosensitive Hydrogel for Regenerative Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 894.

- Thakur, V.K.; Thakur, M.K. Recent advances in graft copolymerization and applications of chitosan: A review. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 2637–2652.

- Thakur, S.; Sharma, B.; Verma, A.; Chaudhary, J.; Tamulevicius, S.; Thakur, V.K. Recent progress in sodium alginate based sustainable hydrogels for environmental applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 143–159.

- Verma, A.; Thakur, S.; Mamba, G.; Gupta, R.K.; Thakur, P.; Thakur, V.K. Graphite modified sodium alginate hydrogel composite for efficient removal of malachite green dye. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 148, 1130–1139.

- Poonguzhali, R.; Khaleel Basha, S.; Sugantha Kumari, V. Novel asymmetric chitosan/PVP/nanocellulose wound dressing: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 112, 1300–1309.

- Deng, P.; Jin, W.; Liu, Z.; Gao, M.; Zhou, J. Novel multifunctional adenine-modified chitosan dressings for promoting wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 260, 117767.

- Masood, N.; Ahmed, R.; Tariq, M.; Ahmed, Z.; Masoud, M.S.; Ali, I.; Asghar, R.; Andleeb, A.; Hasan, A. Silver nanoparticle impregnated chitosan-PEG hydrogel enhances wound healing in diabetes induced rabbits. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 559, 23–36.

- Xue, H.; Hu, L.; Xiong, Y.; Zhu, X.; Wei, C.; Cao, F.; Zhou, W.; Sun, Y.; Endo, Y.; Liu, M.; et al. Quaternized chitosan-Matrigel-polyacrylamide hydrogels as wound dressing for wound repair and regeneration. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 226, 115302.

- Miguel, S.P.; Moreira, A.F.; Correia, I.J. Chitosan based-asymmetric membranes for wound healing: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 127, 460–475.

- Baysal, K.; Aroguz, A.Z.; Adiguzel, Z.; Baysal, B.M. Chitosan/alginate crosslinked hydrogels: Preparation, characterization and application for cell growth purposes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 59, 342–348.

- Zhang, M.; Zhao, X. Alginate hydrogel dressings for advanced wound management. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 162, 1414–1428.

- Ehterami, A.; Salehi, M.; Farzamfar, S.; Samadian, H.; Vaez, A.; Ghorbani, S.; Ai, J.; Sahrapeyma, H. Chitosan/alginate hydrogels containing Alpha-tocopherol for wound healing in rat model. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 51, 204–213.

- Lehnert, S.; Sikorski, P. Tailoring the assembly of collagen fibers in alginate microspheres. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl 2021, 121, 111840.

- Yao, Y.; Zhang, A.; Yuan, C.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y. Recent trends on burn wound care: Hydrogel dressings and scaffolds. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 4523–4540.

- Prudovsky, I. Cellular Mechanisms of FGF-Stimulated Tissue Repair. Cells 2021, 10, 1830.

- Firoozi, N.; Kang, Y. Immobilization of FGF on Poly(xylitol dodecanedioic Acid) Polymer for Tissue Regeneration. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10419.

- Karimi, M.; Maghsoud, Z.; Halabian, R. Effect of Preconditioned Mesenchymal Stem Cells with Nisin Prebiotic on the Expression of Wound Healing Factors Such as TGF-β1, FGF-2, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-10. Regen. Eng. Transl. Med. 2021, 7, 30–40.

- Xie, Y.; Su, N.; Yang, J.; Tan, Q.; Huang, S.; Jin, M.; Ni, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, D.; Luo, F.; et al. FGF/FGFR signaling in health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 181.

- Mossahebi-Mohammadi, M.; Quan, M.; Zhang, J.S.; Li, X. FGF Signaling Pathway: A Key Regulator of Stem Cell Pluripotency. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 79.

- Jin, S.; Yang, C.; Huang, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Q.; Yang, P. Conditioned medium derived from FGF-2-modified GMSCs enhances migration and angiogenesis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 68.

- Sasaki, J.I.; Zhang, Z.; Oh, M.; Pobocik, A.M.; Imazato, S.; Shi, S.; Nor, J.E. VE-Cadherin and Anastomosis of Blood Vessels Formed by Dental Stem Cells. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 437–445.

- Duong, C.N.; Vestweber, D. Mechanisms Ensuring Endothelial Junction Integrity Beyond VE-Cadherin. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 519.

- Gao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, J.H.; Wang, X.P.; Cao, L.; Chen, G.Q.; Mao, H.L.; Bi, X.D.; Gu, Z.W.; Yang, J. VE-cadherin functionalized injectable PAMAM/HA hydrogel promotes endothelial differentiation of hMSCs and vascularization. Appl. Mater. Today 2020, 20, 100690.

- Huang, L.X.; Abdalla, A.M.E.; Xiao, L.; Yang, G. Biopolymer-Based Microcarriers for Three-Dimensional Cell Culture and Engineered Tissue Formation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1895.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!