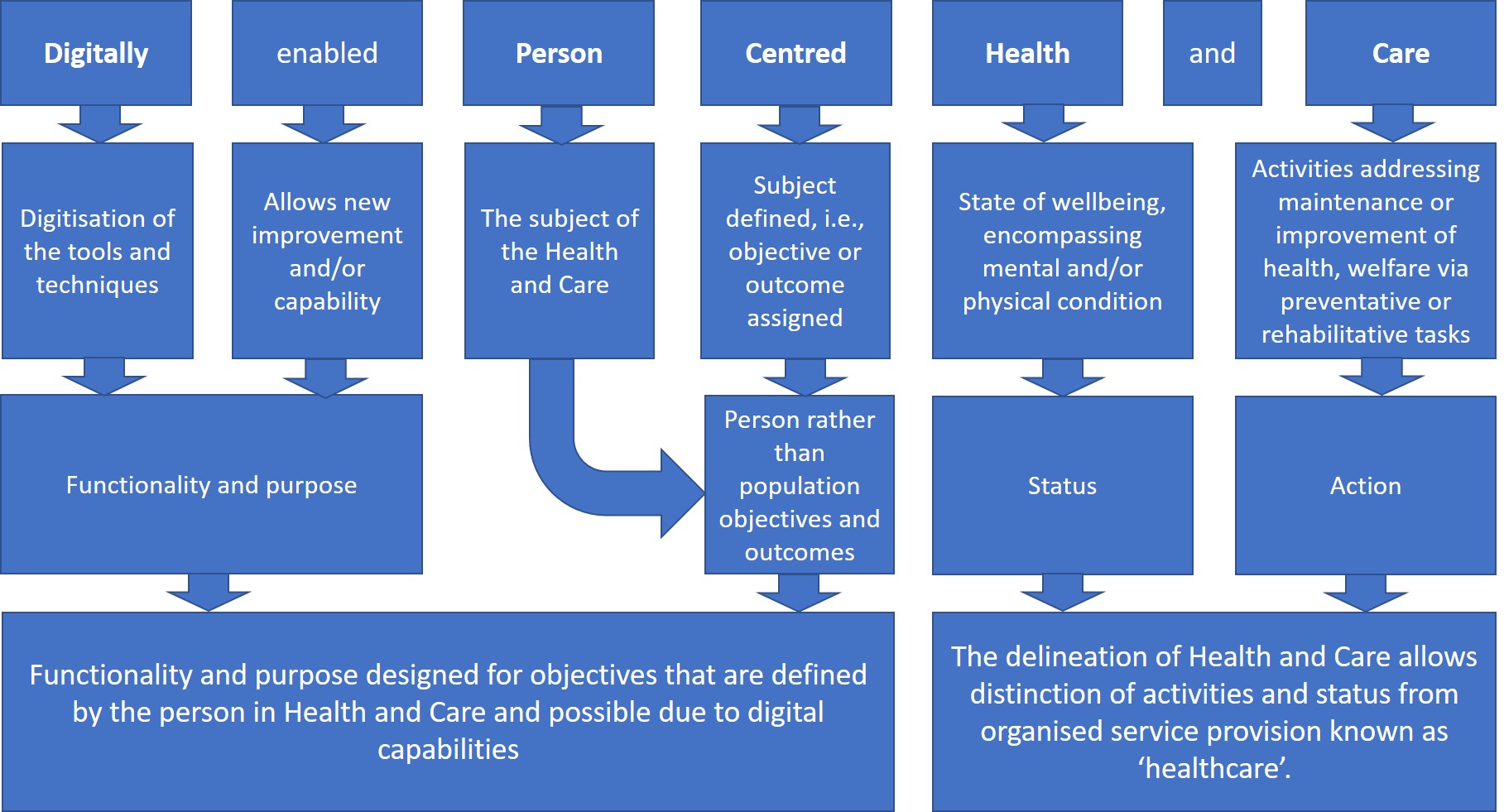

Digitally enabled Person Centred Health and Care [DePCHaC] is term applicable to activities aimed at addressing health or providing care that use digital tools and functionality that has been specifically targeted to objectives and outcomes of the person.

- Digital Health

- Person Centred Care

- Health

- Digital Care

1. Introduction

Digitally enabled Person Centred Health and Care (DePCHaC)is a product of the evolutions in technology, models of care, health related concepts and interdisciplinary applications. Person centred care (PCC) has long been a respected objective of health, care and consequently healthcare services.

2. History

2.1 Person centred care

Person centredness has been discussed across almost if not all fields of health and medicine for several decades, arguing for it's value in improving health care. The purpose and proof as to why we should be doing so however is easily taken for granted in general discussion. Clarity, or at least reminding, on why person centredness should be incorporated is crucial to utilising this effectively. The origin of person centred care was born from the field of psychology half a century ago thanks to Dr Carl Rogers [1] advocating for a shift towards valuing the persons perspective and experience improving success in treatment. The argument for the patient to be respected as an equal partner in health care, notably for decision making, was then discussed as broadly applicable to health and medicine by Tuckett et al in 1985 [2]. In the 1990's Wagner and colleagues [3], as well as Clark et al [4] explicitly discussed the evidence for improving health outcomes in management of chronic health where the person had been given an active or central role in care planning and delivery. In the same era, the psychologist Albert Bandura who initially specialised in social theories of behaviour change [5] found prominence in health psychology where the field of self-efficacy in relation to improving health outcomes [6] was now supported by the counter movement from medical researchers. Chronic health by definition requires management over a sustained amount of time and as such is most dependent on the person to be involved in maintaining health and care activities where the physician can only be present and in control for a minority of the disease journey. The inclusion, and arguably, promotion of the patient to a person, especially in chronic health, in increasing levels of control for their health and care journey was now well established and understood to be inherent to allowing the person to be actively involved and in parts responsible for their outcomes. The fundamental purpose of person centred care is therefore one of improving outcomes that can only be achieved with shared control and responsibility rather than simply respecting the person present.

2.2 Digital health

Developments in technology have occurred with increasing pace, and impact driven by an equally increasing variety of drivers and enablers. The digitisation of technology has impacted versatility in information (data) science, along with issues of access (inclusion) among many other factors. The capacity to include the person in the operation of health technologies has been anticipated to improve ability to meet the ideas of person centred care [7]. However the rewards of the digital health revolutions did not automatically allow the goals of improving health outcomes in chronic health to be met [8], with health and care practice also needing more just technology improvements to achieve such goals [9]. Digital health capabilities alone are not in and of themselves the answer to achieving the ideals of person centred care but are tools with which it could.

3. Current status

The practice of PCC has been dependent on discipline specific technological, logistical and clinical practice developments. Digitisation of technology for health and care however has enabled functionality and purpose of digital health tools to be designed for a person centric application. As such, the use of tools that support DePCHaC is part one path to achieving truly Person Centred Care.

References

- Rogers, Carl,. Client-centered therapy; its current practice, implications, and theory; Houghton Mifflin: Oxford, London, 1951; pp. xii, 560-xii, 560.

- David A. Tuckett; Mary Boulton; Coral Olson; A New Approach to the Measurement of Patients' Understanding of What They Are Told in Medical Consultations. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 1985, 26, 27, 10.2307/2136724.

- Wagner, E., Austin, B., Von Korff, M.; Improving outcomes in chronic illness. Managed Care Quarterly 1996, 4; 2, 12-15, .

- Noreen M. Clark; Marshall H. Becker; Nancy K. Janz; Kate Lorig; William Rakowski; Lynda Anderson; Self-Management of Chronic Disease by Older Adults. Journal of Aging and Health 1991, 3, 3-27, 10.1177/089826439100300101.

- Bandura, A; Self-efficacy: Towards a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review 1977, 84; 2, 191-215, 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191.

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Thought control of action; Schwarzer, Ralf, Eds.; Routledge: Oxon, U.K.,, 1992; pp. 3-38.

- Deborah Lupton; The digitally engaged patient: Self-monitoring and self-care in the digital health era. Social Theory & Health 2013, 11, 256-270, 10.1057/sth.2013.10.

- Deede Gammon; Gro Karine Rosvold Berntsen; Absera Teshome Koricho; Karin Sygna; Cornelia Ruland; Lars Kayser; Amy Bauer; The Chronic Care Model and Technological Research and Innovation: A Scoping Review at the Crossroads. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2015, 17, e25, 10.2196/jmir.3547.

- Sophie Brice; Helen Almond; Health Professional Digital Capabilities Frameworks: A Scoping Review. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare 2020, ume 13, 1375-1390, 10.2147/jmdh.s269412.