Patatin-related phospholipases A (pPLAs) are a group of plant-specific acyl lipid hydrolases that share less homology with phospholipases than that observed in other organisms. Out of the three known subfamilies (pPLAI, pPLAII, and pPLAIII), the pPLAIII member of genes is particularly known for modifying the cell wall structure, resulting in less lignin content. Overexpression of pPLAIIIα and ginseng-derived PgpPLAIIIβ in Arabidopsis and hybrid poplar was reported to reduce the lignin content. Lignin is a complex racemic phenolic heteropolymer that forms the key structural material supporting most of the tissues in plants and plays an important role in the adaptive strategies of vascular plants. However, lignin exerts a negative impact on the utilization of plant biomass in the paper and pulp industry, forage digestibility, textile industry, and production of biofuel. Therefore, the overexpression of pPLAIIIγ in Arabidopsis was analyzed in this study. This overexpression led to the formation of dwarf plants with altered anisotropic growth and reduced lignification of the stem.

1. Introduction

The global demand for plant resources for food and fuel consumption has been estimated to increase up to 50%

[1]. Thus, engineering the raw plant materials for valuable biomass is necessary to meet the worldwide energy demand. The cell wall of plant biomass is primarily composed of three biopolymers including cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. It also includes other minor components such as organic acids, tannins, proteins, and secondary metabolites. The composition of lignocellulosic material varies between different plant species, and sometimes becomes an impediment in developing biomass engineering techniques for bioethanol production

[2]. The pretreatment step to separate cellulose from lignin during bioethanol production using plant cell walls is costly. Although lignin is a class of complex aromatic biopolymers that provides fundamental structural support to plant cell walls, the presence of lignin is considered the major cause of biomass recalcitrance. Hence, the level or composition of lignin has been widely studied to improve biomass digestibility and reduce recalcitrance during bioengineering. Plant biomass with less lignin content has been engineered by downregulation or knocking out genes involved in lignin biosynthesis or transcription factors controlling lignin levels

[2]. Our group has also previously reported that the genetic engineering of patatin-related phospholipase

pPLAIIIα from Arabidopsis and

pPLAIIIβ from ginseng by overexpression in Arabidopsis and hybrid poplar reduced the total content of lignin and xylem lignification

[3][4][5]. However, the functional roles of other close homologs

pPLAIIIγ and

pPLAIIIδ focused on lignification were not yet characterized.

The Arabidopsis phospholipase (PLA) superfamily has been classified into four groups

[6][7], including phosphatidylcholine (PC) hydrolyzing PLA

1s, phosphatidic acid (PA)-preferring PLA

1s, secretory low molecular weight PLA

2s (sPLA

2s), and patatin-related phospholipases (

pPLAs). Phospholipases are complex and important enzymes that are involved in many physiological processes in plants, such as lipid biosynthesis and metabolism, stress responses, cellular signal transduction, cell growth regulation, and membrane homeostasis

[6][7]. PLAs act on a phospho- or a galacto-glycerolipid to release free fatty acids and lysophospholipids

[8][9]. Overexpression of

pPLAIIIβ (

pPLAIIIβOE) from native Arabidopsis plant resulted in an increase in all phospholipids and galactolipids, and a decrease in cellulose content without altering lignin content

[10]. One of its homologs,

pPLAIIIα, also displayed similar stunted phenotypes when overexpressed

[11]. However,

pPLAIIIαOE reduced the cellular lipid species to a greater extent than that of the wild-type in Arabidopsis and rice

[11][12]. Contrary to the action of

pPLAIIIβOE that reduced the cellulose content,

pPLAIIIαOE only reduced lignin content without altering cellulose content, with a reduced level of H

2O

2 compared to the control

[11]. These data suggest that distinct and redundant functional roles exist among four isoforms of

pPLAIII genes.

Oxidation of monolignols is required in the final stage of lignin polymerization, and peroxidases (PRXs) are involved in the random cross-linking to facilitate lignin polymerization

[13]. Two PRXs, PRX64 and PRX72, function in the control of the spatiotemporal deposition of lignin during different developmental stages by using differentially distributed oxidative substrates, such as H

2O

2 [13]. Thus, it is important to understand the functional roles of

pPLAIII isoforms in the regulation of lignification of the stem. Therefore, the regulatory role of

pPLAIIIγ was analyzed by overexpression in native Arabidopsis to understand the contribution of each of its isoforms to lignin biosynthesis. Spatial and temporal

pPLAIIIγ expression, phloroglucinol lignin staining, and direct lignin quantification showed that

pPLAIIIγ is also involved in reducing lignin content. Decreased levels of H

2O

2 and downregulation of both transcripts of

PRX64 and

PRX72 further showed a novel pathway of

pPLAIII genes in stem lignification.

2. High Expression of PropPLAIIIγ::GUS in Xylem and Phloem Cells

Our previous study showed that overexpression of

pPLAIIIα [5] and

PgpPLAIIIβ in the Arabidopsis system

[3][5] reduced lignin content in the stem of each transformant. Analysis of spatial expression patterns of promoter::

GUS (

β-glucuronidase) fusion,

PropPLAIIIα::

GUS transformants showed that there was an increased gene expression in the xylem and phloem of cross-sectioned stems

[11]. In this study, independent

PropPLAIIIγ::

GUS transformants were generated, and images were taken throughout different developmental stages to gain insights into the temporal and spatial distribution patterns of

pPLAIIIγ transcripts in the stem (

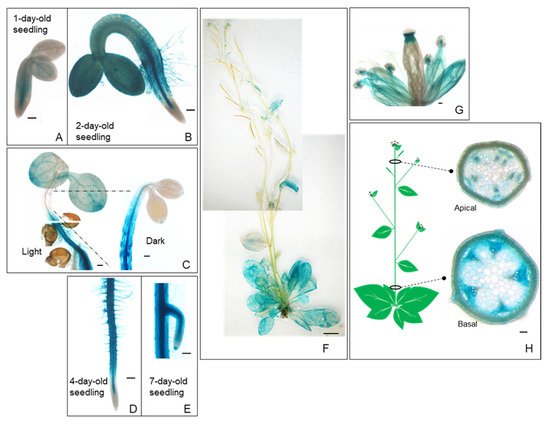

Figure 1). The GUS reporter gene was found to be expressed in most organs, including the seedling, inflorescence, flower, stem, leaf, and root (

Figure 1A–H). These temporal and spatial GUS expression patterns provide additional information in addition to the quantitative real-time PCR results of the root

[10]. The GUS staining became stronger in the hypocotyls of etiolated seedlings compared to those grown in light conditions (

Figure 1C).

PropPLAIIIγ::

GUS was also highly expressed in roots and root hairs with greater restriction in the vasculature (

Figure 1D,E). Intense staining was observed at the junction of the silique and stigma and throughout the vein of sepals in the floral organs (

Figure 1G). Cross-sections of the apical and basal part of the stem show the expression of

PropPLAIIIγ::

GUS in xylem and phloem (

Figure 1H), which is similar to that of our previous study on

PropPLAIIIα::

GUS [11]. These GUS reporter gene expression patterns indicate the possible role of

pPLAIIIγ in stem lignification.

Figure 1. Spatial and temporal expression patterns of pPLAIIIγ gene in Arabidopsis. Histochemical analysis of GUS expression harboring PropPLAIIIγ::GUS at different developmental stages. (A) 1-d-old seedling. (B) 2-d-old seedling. (C) Aerial part of 4-d-old seedlings grown under long day (16 h light/8 h dark) and dark conditions. (D) Root of 4-d-old seedlings. (E) The meristematic zone of the lateral root in 7-d-old seedlings. (F) 6-week-old whole plant. (G) Floral organs. (H) The cross-sections show the GUS expression in the vasculature of the apical and basal parts of the stem. Scale bars = 100 μm (A–E,G,H) and 1 cm (F).

3. Overexpression of pPLAIIIγ Reduced Plant Height

All the overexpression lines of

pPLAIIIαOE [5][11],

pPLAIIIβOE [3][4][10], and

pPLAIIIδOE [14] displayed overall stunted growth patterns with reduced plant height and radially expanded cell elongation. Reduced longitudinal growth patterns, in which the anisotropic cell expansion was disrupted, focused on floral organs and leaves and were very recently published by overexpression of

pPLAIIIγ (

pPLAIIIγOE)

[15]. However, the phenotypic and biochemical characteristics of

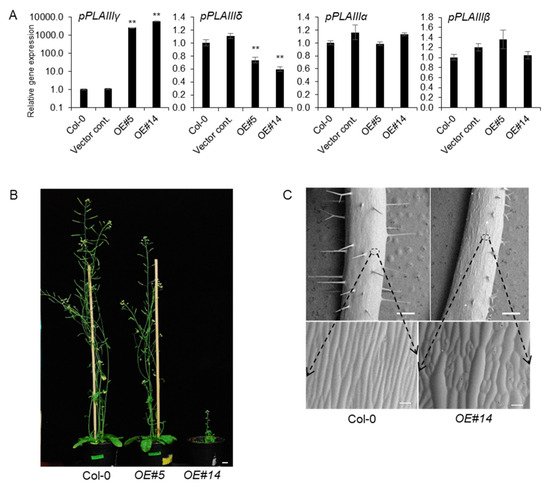

pPLAIIIγOE in stem elongation and lignification were not yet characterized. Two independent transgenic lines under the 35S promoter were chosen for further work out of several transgenic lines that followed the Mendelian law of segregation. Line numbers 5 and 14 were quantified by qPCR and were seen to have 2600-fold and 5800-fold more transcripts, respectively, compared to that of 4-week-old vegetative leaves of Col-0 wild-type (

Figure 2A). Interestingly, the number of

pPLAIIIγ and

pPLAIIIδ transcripts were inversely proportional to each other. However, the mRNA levels of

pPLAIIIα and

pPLAIIIβ were not altered (

Figure 2A), indicating that the function of

pPLAIIIγ might be independent to that of both

pPLAIIIα and

pPLAIIIβ. Two selected transgenic

pPLAIIIγOE lines displayed intermediate and severely dwarfed plant height (

Figure 2B). Isotropic growth patterns

[15] were more distinctively observed in the stem (

Figure 2C), which ultimately led to shorter plant height in OE lines than that in the Col-0 lines.

Figure 2. pPLAIIIγOE shows inhibited longitudinal growth and altered elongation pattern of epidermal cells. (A) Expression levels of each pPLAIII gene in 2-week-old seedlings of controls and pPLAIIIγOE. Each data point represents the average ± SE of three independent replicates at p < 0.01 (**), respectively. (B) Growth phenotype of 7-week-old Col-0 and pPLAIIIγOE. Scale bars = 1 cm. (C) Epidermal cell growth patterns are altered in the pPLAIIIγOE lines. All images were taken using a low-vacuum scanning electron microscope (JSM-IT300, JEOL, Seoul, Korea) at 10.8 mm working distance and 20.0 kV.

4. Overexpression of pPLAIIIγ Reduced Lignin Content in Arabidopsis

Our previous study reported that the overexpression of

pPLAIIIα from Arabidopsis

[5] and

PgpPLAIIIβ from ginseng

[3][4] reduced the lignification of xylem in Arabidopsis and hybrid poplars without altering cellulose content. However, overexpression of

pPLAIIIβOE in Arabidopsis resulted in a reduction in cellulose content

[10]. Therefore, tissue staining and direct measurement of lignin were performed using

pPLAIIIγOE lines to clarify this difference in the modification of cell wall composition by these homologs. Lignin staining and quantification were performed, adding one more transgenic line to obtain more robust confirmatory results.

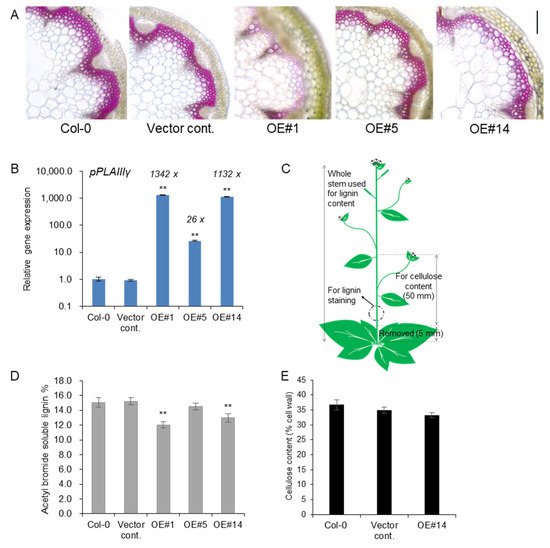

Treatment with phloroglucinol-HCl stain led to a pink color due to the reaction with cinnamaldehyde end-groups of lignin. Reduced lignin staining was observed in xylem cell layers of

pPLAIIIγOE lines compared to the control (

Figure 3A). The transcript levels of

pPLAIIIγ were quantified using the stems used for lignin staining and quantification. Line #1 showed an even higher expression than line #14 (

Figure 3B). This indicated that lines #1 and #14 showed an almost equally high expression of the

pPLAIIIγ gene compared to line #5. Samples used for lignin staining and quantification and cellulose analysis are represented in

Figure 3C. Consistent with the results for the levels of transcripts observed for each line (OE#1 > OE#14 >> OE#5), where OE#1 showed the highest expression, lignin staining of cross-sections was severely decreased in the OE lines, showing an inverse relationship with the degree of gene expression. Direct quantification of lignin content by acetyl bromide further showed significantly decreased lignin content in two highly expressing OE lines (

Figure 3D), which further confirmed the results of phloroglucinol staining (

Figure 3A). The content of cellulose, the other major cell wall component, was not altered (

Figure 3E), although relevant transcripts involved in cellulose biosynthesis

[16] and cellulose production

[17] were slightly upregulated (

Figure S1). Overall, the results strongly indicate that the overexpression of

pPLAIIIγ in the stem ultimately reduced the lignin content.

Figure 3. Lignin content was reduced in stem of pPLAIIIγOEs without altering cellulose content. (A) Phloroglucinol-HCl staining and (B) transcript levels of pPLAIIIγ in controls and OE lines (C) Arabidopsis image showing the parts used for lignin and cellulose analysis. (D) Total content of lignin by acetyl bromide method, and (E) quantification of cellulose content in 7-week-old stems of controls and pPLAIIIγOE. Each data point represents the average ± SE of multiple independent replicates at p < 0.01 (**), respectively. n = 3 (B), n = 4 (D), and n = 5 (E).

5. Lignin-Specific Transcription Factors Are Downregulated in the Stem of pPLAIIIγOE

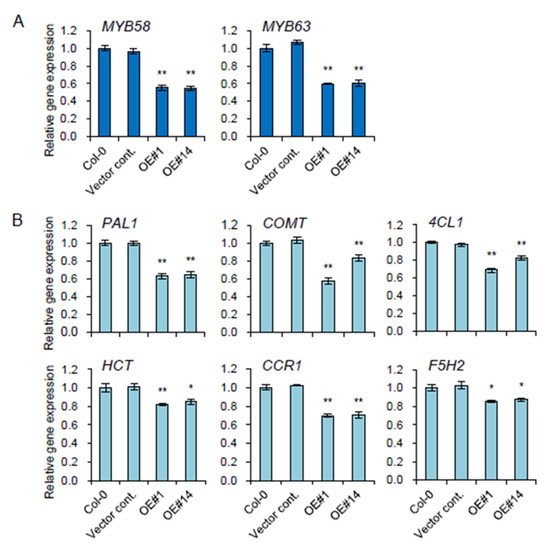

Two key transcription factors,

MYB58 and

MYB63, involved in lignin biosynthesis

[18] were significantly reduced in OE lines (

Figure 4A). Relevant monolignol biosynthetic genes, including

PAL1 (phenylalanine ammonia-lyase 1),

4CL (4-coumarate-CoA ligase)

, HCT (hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA: shikimate/quinate hydroxycinnamoyl transferase)

, COMT (caffeic acid

O-methyltransferase),

CCR1 (cinnamoyl-CoA reductases 1)

, and

F5H (ferulic acid 5-hydroxylase, also named

CYP84A4) were all significantly downregulated in the stem of all the transgenic plants overexpressing

pPLAIIIγ (

Figure 4B). This suggests that

pPLAIIIγOE is involved in the negative regulation of lignification in Arabidopsis.

Figure 4. Genes involved in lignin biosynthesis were downregulated in the stem of pPLAIIIγOE lines. (A) Two transcriptional activators, MYB58 and MYB63, and (B) genes involved in lignin biosynthesis were quantified by qPCR. Each data point represents the average ± SE of three independent replicates at p < 0.05 (*) and p < 0.01 (**), respectively.

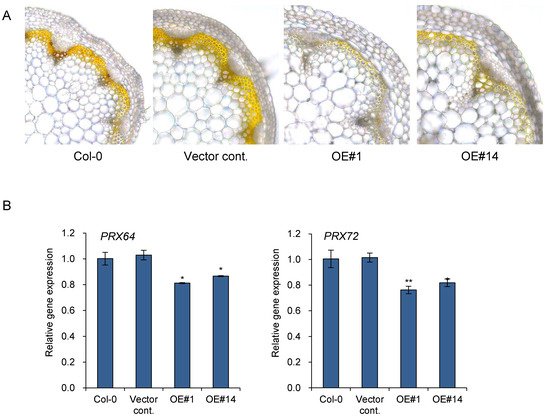

6. Transcripts Encoding Oxidative Enzyme Are Altered in pPLAIIIγOE

Monolignols, which are lignin precursors, are synthesized within the cytosol and subsequently secreted to the apoplastic cell wall where they are oxidized, which initiates random cross-linking to form lignin polymers. Secreted enzymes, namely peroxidases (PRXs), are known to facilitate lignin polymerization by oxidizing lignin monolignols using oxidative substrates such as hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2). It was reported recently that overexpression of

pPLAIIIα led to reduced levels of H

2O

2 in rosette leaves with delayed senescence

[11]. Therefore, the levels of H

2O

2 were monitored in two independent

pPLAIIIγOE. In situ detection of H

2O

2 was performed by staining with 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB)

[19]. DAB was oxidized by H

2O

2 in the presence of heme-containing oxidoreductase to generate a dark brown precipitate. Cross-sections of each stem were visualized after vacuum infiltration to observe the precise localization of DAB staining. The levels of H

2O

2 decreased due to the overexpression of

pPLAIIIγ compared to those of the Col-0 and empty vector controls (

Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Accumulation of hydrogen peroxide was reduced in pPLAIIIγOE lines. (A) 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining and (B) expression levels of two peroxidases, PRX64 and PRX72, in 7-week-old stem. Scale bar = 10 μm. Each data point represents the average ± SE of three independent replicates at p < 0.05 (*) and p < 0.01 (**), respectively.

Lignification appears to be tightly regulated by localized oxidative enzymes and ROS accumulation. PRX64 is expressed in stems and are proven to be involved in lignin polymerization

[20]. Additionally, PRX64, PRX71, and PRX72 were identified as potential enzymes involved in the lignification of the stem out of 73 PRXs identified in Arabidopsis

[13]. PRX72 localize to the thick secondary wall of xylem vessels and fiber cells, while PRX64 localizes to the cell corners and middle lamella of fiber cells

[13]. Quantitative gene expression analysis was performed to further confirm the function of

pPLAIIIγOE in lignification through the regulation of genes encoding oxidative enzymes (

Figure 5B). The two peroxidase genes,

PRX64 and

PRX72, were significantly downregulated in two

pPLAIIIγOE lines (

Figure 5B). Altogether, the results suggest that overexpression of

pPLAIIIγ is involved in reducing stem lignification via the downregulation of

PRX64 and

PRX72.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/plants11020200