Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Oncology

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among men in the Western world. Although localized disease can be effectively treated with established surgical and radiopharmaceutical treatments options, the prognosis of castration-resistant advanced prostate cancer is still disappointing.

- prostate cancer

- angiogenesis

1. Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer is characterized by slow to moderate growth. Consequently, many cases are indolent and in up to 70% of incidentally diagnosed cases over 60 years death is due to an unrelated cause [1]. The five-year relative survival rate for men diagnosed in the USA between 2001 and 2007 with local or regional disease was 100%, whilst the rate for distant disease was 28.7% [2]. UK statistics show similar results: the five-year relative survival for prostate cancer was 100% in localized disease and 30% in distant disease for patients diagnosed during 2002–2006 in the former Anglia Cancer Network [3]. Most cases of prostate cancer are diagnosed by prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing or rarely by rectal examination. Prostate cancer can present with decreased urinary stream, urgency, hesitancy, nocturia, or incomplete bladder emptying, but these symptoms are non-specific and are infrequent at diagnosis [4].

2. Treatment Options in Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer staging is divided into four stages. Stage 1 and 2 cancers are localized to the prostate whilst stage 3 cancers extend into the periprostatic tissue or the seminal vesicle, without involvement of a nearby organ or lymph node and with no distant metastasis [5]. Stage 4 tumors represent those that have spread to nearby or distant organs or lymph nodes [5].

Stage 1 tumors and stage 2 tumors of low and intermediate risk (Table 1) can be followed up by ‘watchful waiting’ or active surveillance and monitoring [6][7]. Watchful waiting has no curative intent, whilst active surveillance and monitoring defers treatment with curative intent to a time when it is needed [6]. Therefore, in active surveillance and monitoring therapy is reserved for tumor progression, with a 1–10% mortality rate [6].

Table 1. Risk stratification of localized prostate cancer according to NICE guidance, UK [7]. Gleason score: histological pattern of the tumor. Stage T1–T2a: tumor involving <50% of one lobe. Stage T2b: tumor involving ≥50% of one lobe. Stage T2c: tumor involving both lobes. NICE stands for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. PSA stands for Prostate-Specific Antigen.

| Level of Risk | PSA Level (ng/mL) | Gleason Score | Clinical Stage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk | <10 | and | ≤6 | and | T1–T2a |

| Intermediate risk | 10–20 | or | 7 | or | T2b |

| High risk | >20 | or | 8–10 | or | ≥T2c |

Radical prostatectomy is a treatment option for localized tumors in patients with few comorbidities. Although this provides an improvement in disease progression compared to active surveillance and monitoring, it does not translate into a statistical difference in mortality: 10-year cancer-specific survival rates were 98.8% with active surveillance and monitoring compared to 99% with radical prostatectomy [6]. Complications of radical prostatectomy include the mortality and morbidity associated with major surgery and anaesthesia, penile shortening, impotence, urinary and faecal incontinence, and inguinal hernia [5].

Radiation and radiopharmaceutical treatment options include external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT), interstitial implantation of radioisotopes into the prostate and hormonal manipulation [6]. EBRT is used with curative intent in all stages of prostate cancer, with or without adjuvant hormonal therapy. Interstitial implantation of radioisotopes is used in patient with stage 1 and 2 tumors. Short term results are similar to those seen with EBRT or radical prostatectomy, but the maintenance of sexual potency is significantly higher (86–96%) when compared to radical prostatectomy or EBRT (10–40% and 40–60%, respectively) [8].

Hormonal manipulation options include surgical castration (orchidectomy) or medical castration (LH-RH antagonists) [9]. These may be used in stage 3 or 4 cancers and can be enhanced by the addition of anti-androgenic therapy and adjuvant treatment with bisphosphonates [10]. Recently approved anti-androgen agents include abiraterone acetate, an inhibitor of cytochrome P450c17, a critical enzyme in androgen synthesis and enzalutamide, a second generation androgen-receptor–signaling inhibitor [10][11][12].

Treatment options for high stage metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer include active cellular immunotherapy with sipuleucel-T, which has resulted in increased overall survival in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase 3 trial [13]. This lead to its approval for the treatment of asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients with nonvisceral metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer in 2010. Radium-223 dichloride is used in symptomatic patients with bone metastases and no known visceral metastases [14]. Cabazitaxel, a derivative of docetaxel, is approved as a second line chemotherapy agent [15]. Further possible treatment options to prevent bone metastases include denosumab (a monoclonal antibody that inhibits osteoclast function) [16] and bone-seeking radionucleotides (strontium chloride Sr 89) [17].

Despite a widening arsenal of new treatment options, a cure is rarely achieved in stage 4 prostate cancer, although there is astriking difference in treatment response between individual patients [18]. Such outcomes emphasize the need for research into further treatment options in hormone-refractory advanced prostate cancer. One such emerging therapeutic option is inhibition of tumor-related angiogenesis.

3. Angiogenesis in Cancer

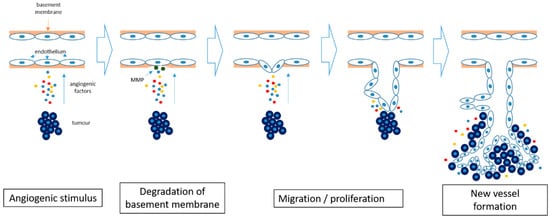

Angiogenesis is defined as the development of new vascular vessels from pre-existing blood vessels. It has a critical role in wound healing and embryonic development and also provides collateral formation for improved organ perfusion in ischaemia [19]. It is a multi-step process triggered by an angiogenic stimulus (Figure 1). The first step of the process is the production of proteases which degrade the basement membrane. This is followed by migration and proliferation of the endothelium, resulting in the formation of a new vascular channel [20].

Figure 1. Angiogenesis in cancer. Hypoxia within the tumor induces the release of pro-angiogenic factors and results in degradation of the basement membrane by matrix metalloproteinases (MMP). The endothelial cells start to differentiate and proliferate, forming new blood vessels. The newly formed blood vessels allow further tumor growth.

Although angiogenesis is not entirely necessary for tumor initialization (some tumors of the brain, lung, and liver can grow along pre-existing vessels) [20], once a tumor reaches a size of more than a few millimeters, formation of new blood vessels is necessary to provide an appropriate blood supply to support tumor cell viability and proliferation. Hence, angiogenesis plays an important role in tumor progression and is now recognized as one of the hallmarks of cancer [21].

Angiogenesis is controlled by a delicate balance between angiogenesis inducers and angiogenesis inhibitors. In a growing cancer there is a constant production of angiogenesis inducers, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF, also known as FGF), angiogenin, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), platelet-derived endothelial growth factor (PDGF), placental growth factor (PGF), transforming growth factor (TGF)-α, TGF-β, interleukin-8 (IL-8), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and epidermal growth factor (EGF) [19]. This constant production of angiogenesis inducers results in increased activity of endothelial cells, as long as the production of anti-angiogenic factors is correspondingly reduced [22]. Among the angiogenesis activators, VEGF-A and bFGF are particularly important in tumor angiogenesis. The abundance and redundant activities of different angiogenesis inducers may explain the resistance or suboptimal effectiveness of anti-angiogenic therapies, when inhibitors acting only on a single angiogenesis activator are being used [22].

Under normal conditions, angiogenesis inducers are balanced by naturally occurring angiogenesis inhibitors, such as endostatin, angiostatin, IL-1, IL-12, interferons, metalloproteinase inhibitors, and retinoic acid [22][23]. These inhibitors can either disrupt new vessel formations or can help to remove already formed vascular channels. Shifting the balance towards angiogenesis inhibition can interfere with important physiological roles of angiogenesis, such as in embryo development, wound healing, and renal function. Interference with wound healing is a particularly important concern in cancer treatment, for example resulting in delayed post-operative healing [24]. Another example involves the inhibition of VEGF-A, resulting in vasoconstriction by means of elevated NO production, consequently elevating blood pressure [25], and increasing the risk of thrombogenesis, resulting in stroke or myocardial infarction. These factors can potentially limit the use of angiogenesis inhibition in cancer, on account of their potential side effects.

4. Angiogenesis Inhibition in Cancer

Although angiogenesis is an essential factor in tumor progression, by means of new vessel formation, this also means that angiogenesis inhibition may only result in inhibition of further tumor growth and may not actively eliminate the tumor. This, and the redundancy of the numerous angiogenesis inducers as listed above, explain why the utilization of angiogenesis inhibitors as a monotherapy has not proved to be as effective as initially expected [26]. Hence, angiogenesis inhibitor therapeutic regimes may require a combination of several anti-angiogenic strategies or may need to be complemented by other non-angiogenesis related chemotherapeutic agents in order to achieve an optimal therapeutic effect [27].

Based on the target of the therapeutic agent, angiogenesis inhibition can be divided into two main groups: direct and indirect inhibition [28]. Direct inhibitors target growing endothelial cells, whilst indirect inhibitors target the tumor cells or tumor-associated stromal cells. Small molecular fragments (e.g., arrestin, tumstatin, canstatin, endostatin, and angiostatin) are the products of proteolytic degradation of the extracellular matrix, and act as direct inhibitors by means of inhibition of the endothelial cell proliferation and migration induced by VEGF-A, bFGF, PDGF, and interleukins [29]. The direct anti-angiogenic effect of targeting integrins (cellular adhesion receptors), has also been demonstrated [29]; an integrin inhibitor—cilentigide—has been shown to inhibit tumor cell invasion [30]. Unfortunately, even though cilentigide acts both on tumor cells and endothelial cells and could be a prime example of multifactorial treatment, results of clinical trials have proved disappointing so far [31].

The most extensively clinically used direct anti-angiogenic strategy targets VEGF-A or its receptors. VEGF-A binds to its receptors to stimulate the proliferation of endothelial cells via the RAS–RAF–MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) signalling pathway [32]. Bevacizumab is a humanised IgG1 monoclonal antibody against VEGF-A. It selectively binds to circulating VEGF-A, preventing its interaction with its receptor, VEGF-receptor 2, expressed on the surface of endothelial cells. Initial studies showed clinical improvement when bevacizumab was used in combination with chemotherapy in a number of cancers, without a marked increase in toxicity [33]. Subsequently it has been approved as part of a combination therapy in the treatment of various cancers, including metastatic lung, colorectal, and renal cell carcinoma, and as a single agent treatment in adult glioblastoma [34]. However, subsequent studies have revealed adverse effects, including gastrointestinal perforation, nephrotic syndrome, thromboembolism, surgical wound healing complications and hypertension [34][35].

In contrast, indirect angiogenesis inhibition involves an interplay between tumor or stromal cells and angiogenesis. One example involves the inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), a tyrosine kinase receptor. Tumor cell expression and activation of EGFR induces interleukin production, which is demonstrated to promote intratumoral angiogenesis. Thus, blocking the expression and/or activity of EGFR can result in indirect inhibition of angiogenesis [36].

To summarize, a number of anti-angiogenesis drugs have already been approved and are currently used in cancer treatment. This prompts the question whether angiogenesis plays any role in prostate cancer progression and, if so, whether anti-angiogenic therapy would be effective in refractory castration-resistant prostate cancer, for which the current treatment options are limited.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms20112676

References

- Zlotta, A.R.; Egawa, S.; Pushkar, D.; Govorov, A.; Kimura, T.; Kido, M.; Takahashi, H.; Kuk, C.; Kovylina, M.; Aldaoud, N.; et al. Prevalence of prostate cancer on autopsy: Cross-sectional study on unscreened Caucasian and Asian men. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013, 105, 1050–1058.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures; American Cancer Society: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2012/estimated-number-of-new-cancer-cases-and-deaths-by-sex-2012.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2018).

- The National Cancer Registration Service, Eastern Office . Available online: http://www.ncras.nhs.uk/ncrs-east/ (accessed on 14 August 2018).

- Zelefsky, M.J.; Eastham, J.A.; Sartor, A.O. Cancer of the prostate. In Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology, 9th ed.; De Vita, V.T., Jr., Lawrence, T.S., Rosenberg, S.A., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011; pp. 1220–7121.

- PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board. Prostate Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version. 30 April 2018. In PDQ Cancer Information Summaries ; National Cancer Institute (US): Bethesda, MD, USA, 2002. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65915/ (accessed on 19 August 2018).

- Hamdy, F.C.; Donovan, J.L.; Lane, J.A.; Mason, M.; Metcalfe, C.; Holding, P.; Davis, M.; Peters, T.J.; Turner, E.L.; Martin, R.M.; et al. 10-Year Outcomes after Monitoring, Surgery, or Radiotherapy for Localized Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1415–1424.

- Graham, J.; Kirkbride, P.; Cann, K.; Hasler, E.; Prettyjohns, M. Prostate cancer:summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ 2014, 8, 348.

- Ragde, H.; Blasko, J.C.; Grimm, P.D.; Kenny, G.M.; Sylvester, J.E.; Hoak, D.C.; Landin, K.; Cavanagh, W. Interstitial iodine-125 radiation without adjuvant therapy in the treatment of clinically localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer 1997, 80, 442–453.

- The Medical Research Council Prostate Cancer Working Party Investigators Group. Immediate versus deferred treatment for advanced prostatic cancer: Initial results of the Medical Research Council Trial. Br. J. Urol. 1997, 79, 235–426.

- Dearnaley, D.P.; Mason, M.D.; Parmar, M.K.; Sanders, K.; Sydes, M.R. Adjuvant therapy with oral sodium clodronate in locally advanced and metastatic prostate cancer: Long-term overall survival results from the MRC PR04 and PR05 randomizedcontrolled trials. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 872–876.

- James, N.D.; de Bono, J.S.; Spears, M.R.; Clarke, N.W.; Mason, M.D.; Dearnaley, D.P.; Ritchie, A.W.; Amos, C.L.; Gilson, C.; Jones, R.J. Abiraterone for Prostate Cancer Not Previously Treated with Hormone Therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 338–351.

- Scher, H.I.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Taplin, M.E.; Sternberg, C.N.; Miller, K.; de Wit, R.; Mulders, P.; Chi, K.N.; Shore, N.D.; et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1187–1197.

- Kantoff, P.W.; Higano, C.S.; Shore, N.D.; Berger, E.R.; Small, E.J.; Penson, D.F.; Redfern, C.H.; Ferrari, A.C.; Dreicer, R.; Sims, R.B.; et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 411–422.

- Parker, C.; Nilsson, S.; Heinrich, D.; Helle, S.I.; O’sullivan, J.M.; Fosså, S.D.; Chodacki, A.; Wiechno, P.; Logue, J.; Seke, M.; et al. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 213–223.

- De Bono, J.S.; Oudard, S.; Ozguroglu, M.; Hansen, S.; Machiels, J.P.; Kocak, I.; Gravis, G.; Bodrogi, I.; Mackenzie, M.J.; Shen, L.; et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: A randomizedopen-label trial. Lancet 2010, 376, 1147–1154.

- Fizazi, K.; Carducci, M.; Smith, M.; Damião, R.; Brown, J.; Karsh, L.; Milecki, P.; Shore, N.; Rader, M.; Wang, H.; et al. Denosumab versus zoledronic acid for treatment of bone metastases in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: A randomized, double-blind study. Lancet 2011, 377, 813–822.

- Oosterhof, G.O.N.; Roberts, J.T.; de Reijke, T.M.; Engelholm, S.A.; Horenblas, S.; von der Maase, H.; Neymark, N.; Debois, M. ColletteL. Strontium (89) chloride versus palliative local field radiotherapy in patients with hormonal escaped prostate cancer: A phase III study of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, Genitourinary Group. Eur. Urol. 2003, 44, 519–526.

- Fizazi, K.; Tran, N.; Fein, L.; Matsubara, N.; Rodriguez-Antolin, A.; Alekseev, B.Y.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Ye, D.; Feyerabend, S.; Protheroe, A.; et al. Abiraterone plus Prednisone in Metastatic, Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 352–360.

- Rajabi, M.; Mousa, S.A. The Role of Angiogenesis in Cancer Treatment. Biomedicines 2017, 21, 34.

- Winkler, F. Hostile takeover: How tumors hijack pre-existing vascular environments to thrive. J. Pathol. 2017, 242, 267–272.

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674.

- Pavlakovic, H.; Havers, W.; Schweigerer, L. Multiple angiogenesis stimulators in a single malignancy: Implications for anti-angiogenic tumor therapy. Angiogenesis 2001, 4, 259–262.

- Kerbel, R.S. Tumor angiogenesis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 2039–2049.

- Gressett, M.; Shah, S.R. Intricacies of bevacizumab-induced toxicities and their management. Ann. Pharmacother. 2009, 43, 490–501.

- Kamba, T.; McDonald, D.M. Mechanisms of adverse effects of anti-VEGF therapy for cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2007, 96, 1788–1795.

- Ferrara, N. VEGF as a therapeutic target in cancer. Oncology 2005, 69 (Suppl. 3), 11–16.

- Carmeliet, P.; Jain, R.K. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature 2011, 473, 298–307.

- El-Kenawi, A.E.; El-Remessy, A.B. Angiogenesis inhibitors in cancer therapy: Mechanistic perspective on classification and treatment rationales. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 170, 712–729.

- Mundel, T.M.; Kalluri, R. Type IV collagen-derived angiogenesis inhibitors. Microvasc. Res. 2007, 74, 85–89.

- Kurozumi, K.; Ichikawa, T.; Onishi, M.; Fujii, K.; Date, I. Cilengitide treatment for malignant glioma: Current status and future direction. Neurol. Med. Chir. 2012, 52, 539–547.

- Su, J.; Cai, M.; Li, W.; Hou, B.; He, H.; Ling, C.; Huang, T.; Liu, H.; Guo, Y. Molecularly Targeted Drugs Plus Radiotherapy and Temozolomide Treatment for Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Oncol. Res. 2016, 24, 117–128.

- Herbert, S.P.; Stainier, D.Y. Molecular control of endothelial cell behaviour during blood vessel morphogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011, 12, 551–564.

- Margolin, K.; Gordon, M.S.; Holmgren, E.; Gaudreault, J.; Novotny, W.; Fyfe, G.; Adelman, D.; Stalter, S.; Breed, J. Phase Ib trial of intravenous recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody to vascular endothelial growth factor in combination with chemotherapy in patients with advanced cancer: Pharmacologic and long-term safety data. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 19, 851–856.

- Ferrara, N.; Adamis, A.P. Ten years of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 385–403.

- Li, M.; Kroetz, D.L. Bevacizumab-induced hypertension: Clinical presentation and molecular understanding. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 182, 152–160.

- Minder, P.; Zajac, E.; Quigley, J.P.; Deryugina, E.I. EGFR Regulates the Development and Microarchitecture of Intratumoral Angiogenic Vasculature Capable of Sustaining Cancer Cell Intravasation. Neoplasia 2015, 17, 634–649.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!