Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Agriculture, Dairy & Animal Science

Congenital hearing loss (i.e., hearing impairment present at birth) is recognized in humans and other terrestrial species, but there is a lack of information on congenital malformations and associated hearing loss in pinnipeds (seals, sea lions, and walruses). Baseline knowledge on marine mammal inner ear malformations is essential to differentiate between congenital and acquired abnormalities, which may be caused by infectious agents, age, or anthropogenic interactions, such as noise exposure.

- congenital hearing loss

- organ of Corti

- marine mammals

- pinnipeds

1. Introduction

Profound congenital hearing loss (i.e., hearing impairment present at birth) is present in 1–3 children out of 1000 [1][2]. Around 50 to 60% of cases of congenital hearing loss are due to a genetic etiology, while the remainder may be attributed to environmental factors, including noise exposure, ototoxic drug exposure, and protozoal, bacterial, or viral infections [3][4]. Genetic mechanisms of congenital hearing loss are divided into syndromic (when hearing loss occurs along with a variety of other malformations) or non-syndromic (when hearing loss is the only apparent abnormality, which accounts for approximately 70% of cases of genetic-related hearing loss) [5][6]. In humans, half of all the non-genetic causes of congenital hearing loss are attributed to infectious pathogens, including Toxoplasma gondii, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes, and syphilis infections. Within these infectious agents, congenital cytomegalovirus is the most common cause of non-hereditary sensorineural hearing loss in childhood [2].

The organ of Corti (hearing organ) in mammals is formed by sensory cells that are typically arranged in one row of inner hair cells (IHCs) and three parallel rows of outer hair cells (OHCs). While OHCs amplify the incoming signal and are responsible for frequency sensitivity and selectivity, IHCs transduce the mechanical sound stimulation into the release of neurotransmitters onto the afferent auditory nerve fibers that conduct the auditory information to the brainstem. In mammals, low frequencies are encoded in the apex (apical region or tip of the spiral), and the high frequencies are encoded in the base of the cochlea, closer to the stapes.

Structural alterations can occur as a consequence of severe noise exposure, including loss of entire hair cells, alterations in stereocilia, nuclei karyorrhexis and karyopycknosis, and degeneration of type I innervation, among others [7][8]. Following cochlear hair cell apoptosis, neighboring supporting cells initiate the elimination of the hair cell, leaving a distinct “scar.” This scarring process results in the simultaneous expansion of the supporting cells and sealing of the reticular lamina [9]. The presence of scars among hair cell rows is an important criterion that can be used to assess a possible history of noise-induced hearing loss [10]. However, potential lesions due to noise exposure and other environmental factors in stranded marine mammals can be confused with hair cell loss due to congenital malformations.

Therefore, it is imperative to develop baseline information on the pathogenesis and prevalence of congenital hearing loss in marine mammals, to further differentiate among congenital or acquired lesions, such as infectious pathogens or anthropogenic interactions associated with noise overexposure. Clinical and pathologic examination of neonates provides the optimal information on congenital hearing loss since it is less likely that they have been exposed to any agent that might cause hair cell damage after birth.

2. Inner Ear Analysis

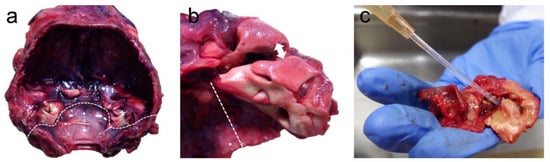

The head was removed, and the inner ears were collected at the University of British Columbia (UBC) within 4.25 h post-mortem. The skull was opened with a hand saw to extract the brain, and the occipital bone was removed with a chisel T-Shape (Virchow skull breaker) post-mortem from the occipitomastoid suture (Figure 1a). The ear bones (periotic and tympanic) were separated and extracted from the squamosal bone using a chisel T-shape (Figure 1b), and the inner ears were perfused perilymphatically with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1M cacodylate buffer (Figure 1c), changed the media into 0.1M cacodylate buffer the following day, and subsequently processed for ultrastructural evaluation, following a previously optimized protocol for marine mammals [10][11][12][13].

Figure 1. (a) Skull after the extraction of the brain with the location of the ears (asterisks). The dotted line indicates the position of the occipitomastoid suture, where the chisel is placed to remove the occipital bone. (b) Separation of the periotic from the tympanic bone by first placing the chisel in the location highlighted with the double arrow, and collection of the periotic bone by sectioning the squamosal bone through the dotted line. (c) The final step of the perilymphatic perfusion through the oval window with fixative, after extracting the stapes and perforating the round and oval window membranes with a small needle.

3. Post-Mortem Examination

The animal presented for necropsy in moderate body and good post mortem condition. Morphologic diagnoses included marked bronchopneumonia, with transmural vasculitis and atelectasis, multifocal necrotizing adrenocortical adenitis with intralesional inclusions consistent with phocid herpesvirus infection, hepatocellular hemosiderosis, splenic extramedullary hematopoiesis, and renal congestion. No bacteria were recovered from the lung, but light Pseudomonas aeruginosa was cultured from the spleen, with moderate mixed growth of Staphylococcus sp., Corynebacterium sp., Psychrobacter sp., Escherichia coli, and Enterococcus sp. isolated from a lymph node. Based on the nature of the bacterial isolates and histopathology (vasculitis and pneumonia), the Pseudomonas aeruginosa was considered significant. The lack of more significant growth from the lung was attributed to antemortem antimicrobial administration. Molecular studies of pooled tissues (striated muscle, diaphragm, heart, and liver) [14] did not detect Apicomplexa, including T. gondii.

4. Inner Ear Analysis

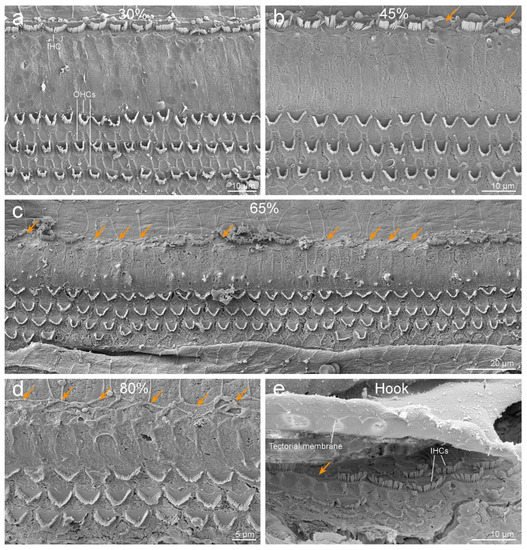

Ultrastructural evaluation of the organ of Corti revealed selective IHC loss throughout the cochlear spiral (Figure 2). While the OHCs were present forming three and often scattered four rows (Figure 2c), there was a loss of IHCs, which was more severe towards the base of the cochlea. The loss of IHCs was determined by the detection of scars, resulting from the overgrowth of adjoining, supporting cells (orange arrows in Figure 2).

Figure 2. Scanning electron microscopy images of the organ of Corti of the left ear along the cochlear spiral, at 30% (a), 45% (b), 65% (c), and 80% (d) distances from the apex. Note that while the outer hair cells (OHCs) are present forming three (and sometimes four) rows, there is a loss of inner hair cells (IHCs, highlighted with orange arrows), with increasing severity towards the base. (e) First IHCs of the hook. The three first IHCs are arranged in two rows. The undersurface of the tectorial membrane shows the imprints where the stereocilia of OHCs are inserted.

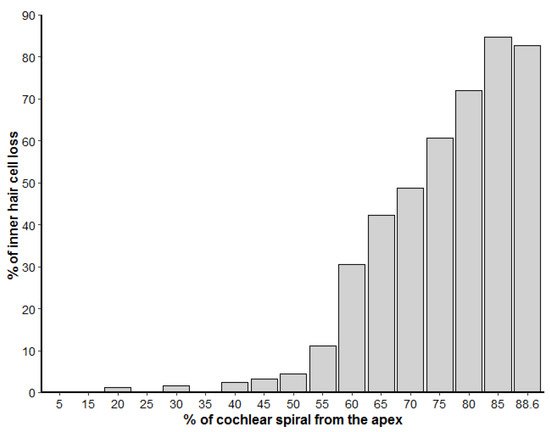

The left cochlea was better dissected and exposed than the right. The cochlear length was 27.19 mm. In the left ear, because the basilar membrane was artefactually folded, the sensory cells of the organ of Corti from the hook region (88.6% to 99% from the apex) could not be assessed. However, the rest of the cochlea was well preserved, with some signs of post-mortem decomposition due to delay between the death of the individual and the fixation of the inner ear. The number of IHCs present and absent were counted every 5% of the cochlear length. There was little loss of IHCs in the apical region, up to 35% from the apex, and an increasing trend of IHC loss towards the base of up to 84.6% loss of IHCs at 80 to 85% of the apex (Figure 3). The exposed areas of the hook region featured a similar pattern of IHC loss. However, in the first 50 µm of the hook, IHCs were present, with the three first IHCs arranged in two rows (Figure 2e).

Figure 3. Loss of inner hair cells along the left cochlear spiral, represented in percentage from the apex. The number of inner hair cells was calculated for each 5% increment of the cochlear length.

The right cochlea was well preserved, especially in the region of the apical and middle turns. However, there was a dissection and processing artifact that hampered the ultrastructural evaluation of the reticular lamina of the sensory epithelium in the majority of the basal turn. In those locations where the organ of Corti was visible, there was a comparable distribution of IHCs loss as in the left cochlea, while the OHCs appeared morphologically intact. However, as the regions of the base where the sensory cells were visible were limited, there was insufficient exposure of the right ear to confirm comparable severity in the bilateral loss of IHCs.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ani12020180

References

- Smith, R.; Bale, J.; White, K. Sensorineural hearing loss in children. Lancet 2005, 365, 879–890.

- Belcher, R.; Virgin, F.; Duis, J.; Wootten, C. Genetic and non-genetic workup for pediatric congenital hearing loss. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 536730.

- Morton, N.E. Genetic epidemiology of hearing impairment. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 630, 16–31.

- Raymond, M.; Walker, E.; Dave, I.; Dedhia, K. Genetic testing for congenital non-syndromic sensorineural hearing loss. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 124, 68–75.

- Kalatzis, V.; Petit, C. The fundamental and medical impacts of recent progress in research on hereditary hearing loss. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998, 7, 1589–1597.

- Farooq, R.; Hussain, K.; Tariq, M.; Farooq, A.; Mustafa, M. CRISPR/Cas9: Targeted genome editing for the treatment of hereditary hearing loss. J. Appl. Genet. 2020, 61, 51–65.

- Bredberg, G.; Ades, H.W.; Engström, H. Scanning electron microscopy of the normal and pathologically altered organ of Corti. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 1972, 73, 3–48.

- Hu, B.H.; Guo, W.; Wang, P.Y.; Henderson, D.; Jiang, S.C. Intense noise-induced apoptosis in hair cells of guinea pig cochleae. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 2000, 120, 19–24.

- Raphael, Y.; Altschuler, R.A. Reorganization of cytoskeletal and junctional proteins during cochlear hair cell degeneration. Cell Motil. Cytoskelet. 1991, 18, 215–227.

- Morell, M.; Brownlow, A.; McGovern, B.; Raverty, S.A.; Shadwick, R.E.; André, M. Implementation of a method to visualize noise-induced hearing loss in mass stranded cetaceans. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41848.

- Morell, M.; Lenoir, M.; Shadwick, R.E.; Jauniaux, T.; Dabin, W.; Begeman, L.; Ferreira, M.; Maestre, I.; Degollada, E.; Hernandez-Milian, G.; et al. Ultrastructure of the Odontocete organ of Corti: Scanning and transmission electron microscopy. J. Comp. Neurol. 2015, 523, 431–448.

- Morell, M.; Raverty, S.A.; Mulsow, J.; Haulena, M.; Barret-Lennard, L.; Nordstrom, C.; Venail, F.; Shadwick, R.E. Combining cochlear analysis and auditory evoked potentials in a beluga whale with high-frequency hearing loss. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 534917.

- Morell, M.; Ijsseldijk, L.L.; Piscitelli-Doshkov, M.; Ostertag, S.; Estrade, V.; Haulena, M.; Doshkov, P.; Bourien, J.; Raverty, S.A.; Siebert, U.; et al. Cochlear apical morphology in toothed whales: Using the pairing hair cell—Deiters’ cell as a marker to detect lesions. Anat. Rec. Adv. Integr. Anat. Evol. Biol. 2021, 1–12.

- Gibson, A.K.; Raverty, S.; Lambourn, D.M.; Huggins, J.; Magargal, S.L.; Grigg, M.E. Polyparasitism is associated with in-creased disease severity in Toxoplasma gondii-infected marine sentinel species. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2011, 5, e1142.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!