Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) of the head and neck region, which accounts for 1–2% of all head and neck cancers, is a challenging clinical entity to treat due to its unique clinical and pathologic features and the lack of prospective data guiding ideal treatment approach. This disease is often characterized by a deceivingly indolent presentation followed by perineural invasion (PNI), local recurrence, and metastatic spread. In many cases with nerve invasion, tumor spread along nerve branches can lead to failure at the base of skull—a dreaded complication that is difficult to treat in a salvage setting. This article aims to summarize the current state of radiation treatment for ACC of the head and neck as relevant to the radiation oncologist.

- adenoid cystic carcinoma

- radiotherapy

- perineural invasion

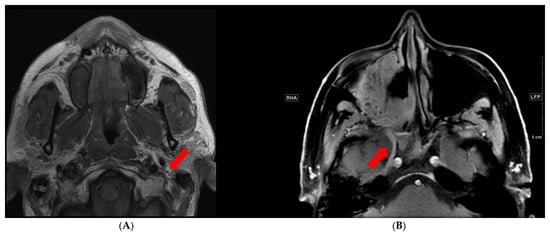

1. Radiologic Evaluation of Perineural Tumor Spread (PNTS)

2. Imaging Techniques

3. Imaging Pitfalls

4. Rationale for Radiation

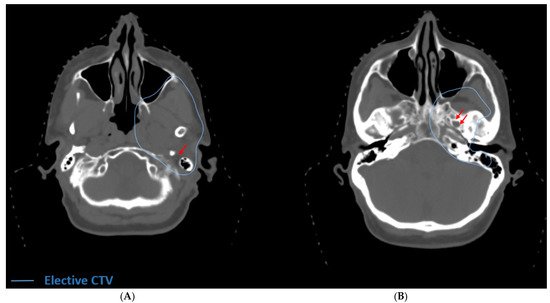

5. Radiation Therapy Design

| Primary ACC Tumor Site | Cranial Nerves at Risk | Origin at Base of Skull | Additional Cranial Nerves at Risk via Inter-Nerve Connections |

|---|---|---|---|

| Submandibular Gland | V3 | Foramen ovale | VII, via chorda tympani (rarely included in elective volumes as involvement is rare) |

| XII (deep lobe involvement) | Hypoglossal canal | ||

| Parotid Gland | VII | Stylomastoid foramen | V3, via auriculotemporal nerve |

| Hard Palate | V2 | V2: foramen rotundum | VII, via greater superficial petrosal nerve and vidian nerve |

6. Particle Therapy

7. Re-Irradiation

8. Concurrent Chemo-Radiotherapy

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers13246335

References

- Nemec, S.F.; Herneth, A.M.; Czerny, C. Perineural tumor spread in malignant head and neck tumors. Top. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2007, 18, 467–471.

- Caldemeyer, K.S.; Mathews, V.P.; Righi, P.D.; Smith, R.R. Imaging features and clinical significance of perineural spread or extension of head and neck tumors. Radiographics 1998, 18, 97–110.

- Penn, R.; Abemayor, E.; Nabili, V.; Bhuta, S.; Kirsch, C. Perineural invasion detected by high-field 3.0-T magnetic resonance imaging. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2010, 31, 482–484.

- Gandhi, M.R.; Panizza, B.; Kennedy, D. Detecting and defining the anatomic extent of large nerve perineural spread of malignancy: Comparing targeted MRI with the histologic findings following surgery. Head Neck 2011, 33, 469–475.

- Ong, C.K.; Chong, V.F. Imaging of perineural spread in head and neck tumours. Cancer Imaging 2010, 10, S92–S98.

- Curtin, H.D. Detection of perineural spread: Fat suppression versus no fat suppression. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2004, 25, 1–3.

- Wu, W.; Wu, F.; Liu, D.; Zheng, C.; Kong, X.; Shu, S.; Li, D.; Kong, X.; Wang, L. Visualization of the morphology and pathology of the peripheral branches of the cranial nerves using three-dimensional high-resolution high-contrast magnetic resonance neurography. Eur. J. Radiol. 2020, 132, 109137.

- Van der Cruyssen, F.; Croonenborghs, T.M.; Hermans, R.; Jacobs, R.; Casselman, J. 3D Cranial Nerve Imaging, a Novel MR Neurography Technique Using Black-Blood STIR TSE with a Pseudo Steady-State Sweep and Motion-Sensitized Driven Equilibrium Pulse for the Visualization of the Extraforaminal Cranial Nerve Branches. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2021, 42, 578–580.

- Baulch, J.; Gandhi, M.; Sommerville, J.; Panizza, B. 3T MRI evaluation of large nerve perineural spread of head and neck cancers. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2015, 59, 578–585.

- Nemzek, W.R.; Hecht, S.; Gandour-Edwards, R.; Donald, P.; McKennan, K. Perineural spread of head and neck tumors: How accurate is MR imaging? Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1998, 19, 701–706.

- Maroldi, R.; Farina, D.; Borghesi, A.; Marconi, A.; Gatti, E. Perineural tumor spread. Neuro. Imaging Clin. N. Am. 2008, 18, 413–429.

- Bur, A.M.; Lin, A.; Weinstein, G.S. Adjuvant radiotherapy for early head and neck squamous cell carcinoma with perineural invasion: A systematic review. Head Neck 2016, 38, E2350–E2357.

- Chatzistefanou, I.; Lubek, J.; Markou, K.; Ord, R.A. The role of perineural invasion in treatment decisions for oral cancer patients: A review of the literature. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 45, 821–825.

- Fagan, J.J.; Collins, B.; Barnes, L.; D’Amico, F.; Myers, E.N.; Johnson, J.T. Perineural invasion in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1998, 124, 637–640.

- Tai, S.K.; Li, W.Y.; Yang, M.H.; Chang, S.Y.; Chu, P.Y.; Tsai, T.L.; Wang, Y.F.; Chang, P.M. Treatment for T1-2 oral squamous cell carcinoma with or without perineural invasion: Neck dissection and postoperative adjuvant therapy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 19, 1995–2002.

- Aivazian, K.; Ebrahimi, A.; Low, T.H.; Gao, K.; Clifford, A.; Shannon, K.; Clark, J.R.; Gupta, R. Perineural invasion in oral squamous cell carcinoma: Quantitative subcategorisation of perineural invasion and prognostication. J. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 111, 352–358.

- Lanzer, M.; Gander, T.; Kruse, A.; Luebbers, H.T.; Reinisch, S. Influence of histopathologic factors on pattern of metastasis in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Laryngoscope 2014, 124, E160–E166.

- Brandwein-Gensler, M.; Smith, R.V.; Wang, B.; Penner, C.; Theilken, A.; Broughel, D.; Schiff, B.; Owen, R.P.; Smith, J.; Sarta, C.; et al. Validation of the histologic risk model in a new cohort of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2010, 34, 676–688.

- Rahima, B.; Shingaki, S.; Nagata, M.; Saito, C. Prognostic significance of perineural invasion in oral and oropharyngeal carcinoma. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. Endod. 2004, 97, 423–431.

- Garden, A.S.; Weber, R.S.; Morrison, W.H.; Ang, K.K.; Peters, L.J. The influence of positive margins and nerve invasion in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck treated with surgery and radiation. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1995, 32, 619–626.

- Balamucki, C.J.; Amdur, R.J.; Werning, J.W.; Vaysberg, M.; Morris, C.G.; Kirwan, J.M.; Mendenhall, W.M. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2012, 33, 510–518.

- Douglas, J.G.; Laramore, G.E.; Austin-Seymour, M.; Koh, W.; Stelzer, K.; Griffin, T.W. Treatment of locally advanced adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck with neutron radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2000, 46, 551–557.

- Pommier, P.; Liebsch, N.J.; Deschler, D.G.; Lin, D.T.; McIntyre, J.F.; Barker, F.G., 2nd; Adams, J.A.; Lopes, V.V.; Varvares, M.; Loeffler, J.S.; et al. Proton beam radiation therapy for skull base adenoid cystic carcinoma. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2006, 132, 1242–1249.

- Gentile, M.S.; Yip, D.; Liebsch, N.J.; Adams, J.A.; Busse, P.M.; Chan, A.W. Definitive proton beam therapy for adenoid cystic carcinoma of the nasopharynx involving the base of skull. Oral Oncol. 2017, 65, 38–44.

- Lee, A.; Givi, B.; Osborn, V.W.; Schwartz, D.; Schreiber, D. Patterns of care and survival of adjuvant radiation for major salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma. Laryngoscope 2017, 127, 2057–2062.

- Choi, Y.; Kim, S.B.; Yoon, D.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, S.W.; Cho, K.J. Clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Laryngoscope 2013, 123, 1430–1438.

- Shen, C.; Xu, T.; Huang, C.; Hu, C.; He, S. Treatment outcomes and prognostic features in adenoid cystic carcinoma originated from the head and neck. Oral Oncol. 2012, 48, 445–449.

- Catalano, P.J.; Sen, C.; Biller, H.F. Cranial neuropathy secondary to perineural spread of cutaneous malignancies. Am. J. Otol. 1995, 16, 772–777.

- Morris, J.G.; Joffe, R. Perineural spread of cutaneous basal and squamous cell carcinomas. The clinical appearance of spread into the trigeminal and facial nerves. Arch. Neurol. 1983, 40, 424–429.

- Min, R.; Siyi, L.; Wenjun, Y.; Ow, A.; Lizheng, W.; Minjun, D.; Chenping, Z. Salivary gland adenoid cystic carcinoma with cervical lymph node metastasis: A preliminary study of 62 cases. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 41, 952–957.

- Megwalu, U.C.; Sirjani, D. Risk of Nodal Metastasis in Major Salivary Gland Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2017, 156, 660–664.

- Ko, H.C.; Gupta, V.; Mourad, W.F.; Hu, K.S.; Harrison, L.B.; Som, P.M.; Bakst, R.L. A contouring guide for head and neck cancers with perineural invasion. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2014, 4, e247–e258.

- Anwar, M.; Yu, Y.; Glastonbury, C.M.; El-Sayed, I.H.; Yom, S.S. Delineation of radiation therapy target volumes for cutaneous malignancies involving the ophthalmic nerve (cranial nerve V-1) pathway. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2016, 6, e277–e281.

- Mourad, W.; Hu, K.S.; Harrison, L.B. Cranial Nerves IX-XII Contouring Atlas for Head and Neck Cancer. Available online: https://www.rtog.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=B7fuSx-B1GU%3d&tabid=229 (accessed on 13 December 2017).

- Mourad, W.F.; Young, B.M.; Young, R.; Blakaj, D.M.; Ohri, N.; Shourbaji, R.A.; Manolidis, S.; Gamez, M.; Kumar, M.; Khorsandi, A.; et al. Clinical validation and applications for CT-based atlas for contouring the lower cranial nerves for head and neck cancer radiation therapy. Oral Oncol. 2013, 49, 956–963.

- Gluck, I.; Ibrahim, M.; Popovtzer, A.; Teknos, T.N.; Chepeha, D.B.; Prince, M.E.; Moyer, J.S.; Bradford, C.R.; Eisbruch, A. Skin cancer of the head and neck with perineural invasion: Defining the clinical target volumes based on the pattern of failure. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2009, 74, 38–46.

- Biau, J.; Dunet, V.; Lapeyre, M.; Simon, C.; Ozsahin, M.; Gregoire, V.; Bourhis, J. Practical clinical guidelines for contouring the trigeminal nerve (V) and its branches in head and neck cancers. Radiother. Oncol. 2018, 131, 192–201.

- Bakst, R.L.; Glastonbury, C.M.; Parvathaneni, U.; Katabi, N.; Hu, K.S.; Yom, S.S. Perineural Invasion and Perineural Tumor Spread in Head and Neck Cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2019, 103, 1109–1124.

- Leonetti, J.P.; Marzo, S.J.; Agarwal, N. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the parotid gland with temporal bone invasion. Otol. Neurotol. 2008, 29, 545–548.

- Huyett, P.; Duvvuri, U.; Ferris, R.L.; Johnson, J.T.; Schaitkin, B.M.; Kim, S. Perineural Invasion in Parotid Gland Malignancies. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 158, 1035–1041.

- Singh, F.M.; Mak, S.Y.; Bonington, S.C. Patterns of spread of head and neck adenoid cystic carcinoma. Clin. Radiol. 2015, 70, 644–653.

- Holliday, E.B.; Garden, A.S.; Rosenthal, D.I.; Fuller, C.D.; Morrison, W.H.; Gunn, G.B.; Phan, J.; Beadle, B.M.; Zhu, X.R.; Zhang, X.; et al. Proton Therapy Reduces Treatment-Related Toxicities for Patients with Nasopharyngeal Cancer: A Case-Match Control Study of Intensity-Modulated Proton Therapy and Intensity-Modulated Photon Therapy. Int. J. Part. Ther. 2015, 2, 19–28.

- Bhattasali, O.; Holliday, E.; Kies, M.S.; Hanna, E.Y.; Garden, A.S.; Rosenthal, D.I.; Morrison, W.H.; Gunn, G.B.; Fuller, C.D.; Zhu, X.R.; et al. Definitive proton radiation therapy and concurrent cisplatin for unresectable head and neck adenoid cystic carcinoma: A series of 9 cases and a critical review of the literature. Head Neck 2016, 38, E1472–E1480.

- Jensen, A.D.; Nikoghosyan, A.V.; Poulakis, M.; Höss, A.; Haberer, T.; Jäkel, O.; Münter, M.W.; Schulz-Ertner, D.; Huber, P.E.; Debus, J. Combined intensity-modulated radiotherapy plus raster-scanned carbon ion boost for advanced adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck results in superior locoregional control and overall survival. Cancer 2015, 121, 3001–3009.

- Jensen, A.D.; Poulakis, M.; Nikoghosyan, A.V.; Welzel, T.; Uhl, M.; Federspil, P.A.; Freier, K.; Krauss, J.; Höss, A.; Haberer, T.; et al. High-LET radiotherapy for adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck: 15 years’ experience with raster-scanned carbon ion therapy. Radiother. Oncol. 2016, 118, 272–280.

- Ikawa, H.; Koto, M.; Takagi, R.; Ebner, D.K.; Hasegawa, A.; Naganawa, K.; Takenouchi, T.; Nagao, T.; Nomura, T.; Shibahara, T.; et al. Prognostic factors of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck in carbon-ion radiotherapy: The impact of histological subtypes. Radiother. Oncol. 2017, 123, 387–393.

- Lang, K.; Adeberg, S.; Harrabi, S.; Held, T.; Kieser, M.; Debus, J.; Herfarth, K. Adenoid cystic Carcinoma and Carbon ion Only irradiation (ACCO): Study protocol for a prospective, open, randomized, two-armed, phase II study. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 812.

- Huber, P.E.; Debus, J.; Latz, D.; Zierhut, D.; Bischof, M.; Wannenmacher, M.; Engenhart-Cabillic, R. Radiotherapy for advanced adenoid cystic carcinoma: Neutrons, photons or mixed beam? Radiother. Oncol. 2001, 59, 161–167.

- Prott, F.J.; Micke, O.; Haverkamp, U.; Willich, N.; Schüller, P.; Pötter, R. Results of fast neutron therapy of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary glands. Anticancer Res. 2000, 20, 3743–3749.

- Xu, M.J.; Wu, T.J.; van Zante, A.; El-Sayed, I.H.; Algazi, A.P.; Ryan, W.R.; Ha, P.K.; Yom, S.S. Mortality risk after clinical management of recurrent and metastatic adenoid cystic carcinoma. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 47, 28.

- McDonald, M.W.; Zolali-Meybodi, O.; Lehnert, S.J.; Estabrook, N.C.; Liu, Y.; Cohen-Gadol, A.A.; Moore, M.G. Reirradiation of Recurrent and Second Primary Head and Neck Cancer With Proton Therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2016, 96, 808–819.

- Seidensaal, K.; Harrabi, S.B.; Uhl, M.; Debus, J. Re-irradiation with protons or heavy ions with focus on head and neck, skull base and brain malignancies. Br. J. Radiol. 2020, 93, 20190516.

- Jensen, A.D.; Poulakis, M.; Nikoghosyan, A.V.; Chaudhri, N.; Uhl, M.; Münter, M.W.; Herfarth, K.K.; Debus, J. Re-irradiation of adenoid cystic carcinoma: Analysis and evaluation of outcome in 52 consecutive patients treated with raster-scanned carbon ion therapy. Radiother. Oncol. 2015, 114, 182–188.

- Dautruche, A.; Bolle, S.; Feuvret, L.; Le Tourneau, C.; Jouffroy, T.; Goudjil, F.; Zefkili, S.; Nauraye, C.; Rodriguez, J.; Herman, P.; et al. Three-year results after radiotherapy for locally advanced sinonasal adenoid cystic carcinoma, using highly conformational radiotherapy techniques proton therapy and/or Tomotherapy. Cancer Radiother. 2018, 22, 411–416.

- Vischioni, B.; Dhanireddy, B.; Severo, C.; Bonora, M.; Ronchi, S.; Vitolo, V.; Fiore, M.R.; D’Ippolito, E.; Petrucci, R.; Barcellini, A.; et al. Reirradiation of salivary gland tumors with carbon ion radiotherapy at CNAO. Radiother. Oncol. 2020, 145, 172–177.

- Sayan, M.; Vempati, P.; Miles, B.; Teng, M.; Genden, E.; Demicco, E.G.; Misiukiewicz, K.; Posner, M.; Gupta, V.; Bakst, R.L. Adjuvant Therapy for Salivary Gland Carcinomas. Anticancer Res. 2016, 36, 4165–4170.

- Schoenfeld, J.D.; Sher, D.J.; Norris, C.M., Jr.; Haddad, R.I.; Posner, M.R.; Balboni, T.A.; Tishler, R.B. Salivary gland tumors treated with adjuvant intensity-modulated radiotherapy with or without concurrent chemotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2012, 82, 308–314.

- Ha, H.; Keam, B.; Ock, C.Y.; Kim, T.M.; Kim, J.H.; Chung, E.J.; Kwon, S.K.; Ahn, S.H.; Wu, H.G.; Sung, M.W.; et al. Role of concurrent chemoradiation on locally advanced unresectable adenoid cystic carcinoma. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 175–181.