A Body of Knowledge (BOK) is a concept used to represent concepts, terms, and activities that make up a professional domain. In addition, an Open BOK is necessary because it allows us to develop the abilities and talents of professionals in different Knowledge Areas (KAs).

- Body of Knowlege

- Education

- OpenBok

Note:All the information in this draft can be edited by authors. And the entry will be online only after authors edit and submit it.

1. Introduction

The goal of knowledge description is to reach a consensus on the core subsets of the knowledge characterizing engineering disciplines [3], and it is a well-known fact that developing an Open BOK is a complex task. This is done by considering the fact that knowledge can often be represented as interconnected BOK, KAs, Knowledge Units (KUs), and Knowledge Topics (KTs) [3].

The main guide that is used for the description of the necessary knowledge of technical academic disciplines is Software Engineering Body of Knowledge (SWEBOK V. 3.0) [3], which generally describes accepted knowledge about Software Engineering (SE). This guide is taken as a reference for the implementation of SE in industrial contexts [4–6], in educational contexts [7–10], and in Information Technology (IT), Governance, where the focus is on how the knowledge is being described [11].

In accordance with [12], from 2000 to 2010, knowledge was represented as knowledge, skills, and attitudes accepted and applied by investment professionals worldwide.

Furthermore, in [13] it is mentioned that knowledge was often written in a specific language with rules and algorithms that are not compatible with other Knowledge-Based Information Technology (KBE-IT) frameworks. In short, articulating an Open BOK is of paramount importance, because it is an essential step to develop an academic profession [14]. Nevertheless, a set of widely agreed guidelines on how to develop these BOKs and, more specifically, on the way to describe the knowledge, is not yet available.

2. Open BOK Context

First, Open BOK is used by those who are interested in expanding their skills and professional training in different areas of knowledge. For the scientific community, BOK allows for the widening of the spectrum of research fields based on consensus and highlights similarities between disciplines [65]. For example, BOK highlights techniques used in materials science that are common between chemistry and physics [66].

Regarding the knowledge levels of a BOK, the amount of knowledge that will be offered within an educational program is defined in [67]. BOK has a specific structure according to the area of engineering or science in which they are applied.

Second, according to [36,66], to establish the description of the BOK, it is necessary to consider the Core Book (CB), and Context Domain (CD) of the BOK study area. In the same way, BOK must establish their respective KAs. Each description of KAs should use the structure shown in [3].

Moreover, as part of this second finding, it can be said that KA divided into smaller divisions called KU [33,36,64,66], which represent individual thematic modules within a KA. Each KU is subdivided into a set of topics, which are the lowest level of the hierarchy. The themes depend on the evolution and context of the KAs and the discipline.

Third, in the Open BOK context, it is also necessary to standardize a knowledge updating process according to how advanced the discipline is and the existing needs of the communities. In general, BOK has different committees, organizations, and collaborative groups that develop and update their contexts considering the progress of science and its areas of knowledge.

Fourth, in order to build an Open BOK with a bottom-up approach (Knowledge Sweep), researchers must consider the ‘materials’ from which the knowledge is extracted by the discipline-directed. When analyzing these materials, it is assumed that a certain degree of knowledge could be obtained and used to formulate an Open BOK.

The reference materials will be the scientifically agreed information [2,3,9,10], and the matrix of topics is divided into details in order to establish its relationship with the respective materials.

Moreover, a list of readings should be considered to complement the information of the proposed KAs. In the same context, when an Open BOK knowledge is developed, it is necessary to establish the origin of the information.

Fifth, it was found that there exist structures, elements, descriptions, and learned lessons of the BOK evolution. In order to show the evolution of BOK, this entry provides the structure, versions, and learned lessons synthesized in Table 1.

Table 1. Structure and version of relevant bodies of knowledge.

|

Body of Knowledge Name |

Structure |

Versions |

|

|

B1: BOK for MPM [40]. |

The Structure of the BOK has been outlined to identify the various knowledge, and skills required by today’s medical practice executive [40]. |

Three versions [39]. |

|

|

B2: Usability Body of Knowledge [41]. |

The Body of Knowledge is organized in an architectural hierarchy [41]. |

Conditions, and circumstances that are relevant to an event, fact or knowledge, in the process of being organized. |

|

|

B3: The Personal Software Process (PSP) Body of Knowledge [42]. |

This BOK is organized in an architectural hierarchy in which the concepts and skills of the PSP are described and decomposed into three levels of abstraction [42]. |

Unique version [42]. |

|

|

B4: SLA BOK [43]. |

The SLA BOK is organized by competency clusters and knowledge areas. Individual competencies (CMP) include skills, related competencies, examples and high maturity skills [43]. |

Unique version [43]. |

|

|

B5: SWEBOK [3]. |

Hierarchical structure using different levels of topics. |

Three version [3]. |

|

|

B6: PMBOK [44]. |

Hierarchical structure using different levels of topics. |

Six versions [44]. |

|

|

B7: ITS BOK [45]. |

Structured by well-defined competencies, notional security roles, four primary functional perspectives, and an IT Security Role, Competency, and Functional Matrix. |

Unique version [45]. |

|

|

B8: WEBOK [46]. |

Hierarchical structure using different levels of topics [46]. |

Unique version [49]. |

|

|

B9: ITBOK. |

Hierarchical structure. 13 knowledge areas [46]. |

Unique version [46]. |

|

|

B10: SEBOK [47]. |

Sevent parts. |

SEBOK has versions 1.0 to 1.4 with very small changes in between. [47]. |

|

|

B11: BKCASE [48]. |

The BKCASE project is of courses structured similarly as the SEBOK itself [48]. |

Three versions [48]. |

|

|

B12: EABoK [68] |

Hierarchical structure. |

Unique version [68]. |

|

Sixth, another finding of this article is the establishment of a general structure of an Open BOK in engineering. This structure begins with the set of KAs, continues KUs, and ends with topics according to the research area.

Seventh, Open BOKs provide the foundation for curriculum development and maintenance [69].

Open BOK promotes integrations and connections with other related disciplines [70].

Eighth, at the level of professional education in engineering contexts BOK, should provide the following detail levels [70]:

- Know the basic concepts and the main areas of application.

- Know the basic technologies and their relationship with basic concepts.

- Know both authorized and unauthorized sources of information, and how to evaluate the quality of the information.

- Have the ability to work with standards.

3. Open BOK in an Educational Context

Furthermore, as part of this finding, educational programs in engineering and engineering technology have been developed to address many aspects associated with computer science [71]. For example, the BOK of Computer Science Technology, the SWEBOK, and the IT BOK are based on inputs provided from various perspectives, including industry demand, previous works in the creation of computer BOKs, and institutional factors.

Knowledge should reflect current best practices, which inevitably change over time. However, updates cannot be carried out in an uncontrolled manner, since associated conferences and other educational materials must be kept in line with the BOK [72].

Finally, other important factors to consider in BOK are the Stakeholders [9], which are people, groups, companies, and either organizational or governmental entities that have an interest in educational programs.

All interested parties must be identified as well as their responsibilities towards educational programs based on BOK (RaPSEEM) [71]. An Open BOK has an important role in the advancement of an area as a knowledgeable practice [72]. SE is a young field of human experience if compared with others. However, the knowledge in this field has evolved at a very high speed, which is a characteristic of Computer Science in general [73].

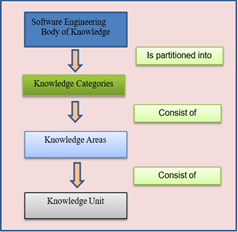

SWEBOK provides a consensually validated characterization of the bounds of the software engineering discipline and to provide access to the BOK supporting that discipline [74]. On the other hand, SWEBOK [3] is oriented toward the private and public sector for this reason, the aims of the SWEBOK guide in the process of training, education, and evaluation of professional of software engineering. The SWEBOK knowledge architecture in this report provides a hierarchical description and decomposition of a body of knowledge for software engineering [75].

For the purposes of this article, the term “knowledge” is used to describe the whole spectrum of content for the discipline: information, terminology, artifacts, data, roles, methods, models, procedures, techniques, practices, processes, and literature [76].

The GSWEBOK is a good first step in characterizing the contents of the software engineering discipline and in providing topical access to the SWEBOK.

Figure 1 shows the three levels of abstraction and the relationships that were used in modeling SWEBOK v 3.0.

Figure 1. Levels of abstraction of SWEBOK [3].

A hierarchical description of software engineering knowledge that organizes and structures the knowledge into three levels of hierarchy KC, KA, and KU [3]; in the same context, the highest level of the hierarchy is the education KA, representing a particular subdiscipline of SE that is generally recognized as a significant part of the SWEBOK that an undergraduate should know [48]. In particular, the curricular recommendations for an undergraduate degree program as put forward by the Working Group on SEET are considered [77].

4. Elements to Describe Knowledge on Open BOK

The Curriculum of SEE evolved in terms of a new design, revised, minor and major changes [78]. Software engineering curriculum (SEC) implementation and assessment in academia took place in different regions all over the world [79]. The process of building the Open BOK should assist in highlighting similarities across disciplines, for example, techniques used in materials science [80].

Elements needed to describe Open BOK is presented in Table 2. These elements permit an adequate description of Open BOK.

Table 2. BOK elements to describe knowledge on Open BOK.

|

Elements |

Association |

Description |

|

|

C1. Domain |

C1.1 Context |

Knowledge identified by name, context, and application. |

|

|

C1.1.1 BOK Application |

|||

|

C1.2 Stakeholders |

|||

|

C1.3 Education |

|||

|

C1.4 Industry |

|||

|

C2. Knowledge Organization |

C2.1 BOK Content |

The conditions, and circumstances that are relevant to an event, fact or knowledge, in the process of being organized. |

|

|

C2.1.1 Disciplines |

|||

|

C2.2 Structure |

|||

|

C2.2.1 Knowledge Categories |

|||

|

C2.2.2 Hierarchical Organization |

|||

|

C2.2.2.1 Knowledge Areas |

|||

|

C2.2.2.1.1 Organization of Knowledge Area |

|||

|

C2.2.2.1.2 Breakdown of Topics |

|||

|

C2.2.2.1.2.1 List of Future Readings |

|||

|

C2.2.2.1.2.2 List of Acronyms |

|||

|

C2.2.2.1.2.3 References |

|||

|

C2.2.2.1.2.3.1 Materials |

|||

|

C2.2.2.1.2.3.2 Matrix |

|||

|

C2.2.2.1.2.3.3 Related Disciplines |

|||

|

C2.2.2.1.2.4 Taxonomies |

|||

|

C2.2.2.1.2.4.1 Types of Taxonomies |

|||

|

C2.2.2.1.2.4.2 Levels of Taxonomies |

|||

|

C2.2.2.1.2.4.3Application of Taxonomies |

|||

|

C2.2.2.1.3 Knowledge Organization |

|||

|

C2.2.2.1.3.1 Knowledge Unit |

|||

|

C2.2.2.1.3.1.1 Knowledge Topic |

|||

|

C2.2.2.1.3.1.2 Knowledge Subtopic |

|||

|

C3. Knowledge Representation |

C3.1 Concepts |

Characteristics to represent knowledge in an educational context. |

|

|

C3.2 Supporting Tools |

|||

|

C3.3 Ontology |

|||

|

C3.3.1 Models |

|||

|

C3.3.2 Vocabulary |

|||

|

C3.4. Skills |

|||

|

C3.4.1.1Instructional Skills |

|||

|

C3.4.1.1.1 Types of Skills |

|||

|

C3.4.1.1.1.1 Technical |

|||

|

C3.4.1.1.1.2 Pedagogical |

|||

|

C3.4.1.2 Capacities |

|||

|

C3.4.1.3 Capabilities |

|||

|

C4. Domain Management |

C4.1. BOK Areas |

Structure of BOKs, where topics are thoroughly detailed. |

|

|

C4.2 BOK Details |

|||

|

C4.3 BOK Structure |

|||

|

C5. Knowledge Acquisition |

C5.1Types of Standards |

Ways to acquire Knowledge. |

|

|

C5.2 Application of Standards |

|||

|

C6. Evolution Boks |

C6.1 Consensus |

Any process of formation, growth or development in the BOK context. |

|

|

C6.2 BOK Objective |

|||

|

C6.2.1 Scope of BOK |

|||

|

C6.3 Type of BOK |

|||

|

C6.4 Knowledge Acquisition |

|||

|

C6.4.1 Lessons Learned |

|||

|

C6.4.2 Material |

|||

|

C7. Knowledge Resource |

C7.1 Guides |

Resources about the BOK. |

|

|

C7.2 Communities |

|||

|

C7.3 Standards |

|||

|

C8. Knowledge Education |

C8.1 Education |

A set of characteristics that identify a knowledge within the educational context |

|

|

C8.1.1 Profile |

|||

|

C8.1.2 Guidelines for Profiles |

|||

|

C8.1.3 Educational Institution |

|||

|

C8.1.4 Educational Training |

|||

|

C8.1.4.1University Curricula |

|||

|

C8.1.4.1.1 Curriculum |

|||

|

C8.1.4.1.1.1Curriculum Process |

|||

|

C8.1.4.1.1.2 Curriculum Develop |

|||

|

C8.1.4.1.1.3Curriculum Resource |

|||

|

C8.1.4.1.1.4 Curriculum Architecture |

|||

|

C8.1.4.1.1.5 Code of Ethics |

|||

|

C8.1.4.2 BOK Accreditation |

|||

|

C8.1.5 Professional Certification |

|||

|

C8.1.5.1 Evaluation Policies |

|||

|

C8.1.5.2 Licensing |

|||

|

C8.1.5.2.1 Competences |

|||

|

C8.1.5.2.2 Certification |

|||

|

C8.1.5.3 Professional Standard |

|||

|

C8.1.5.4 Professional Practice |

|||

|

C8.1.5.5 Professional Development |

|||

|

C8.1.6 Educational Objectives |

|||

|

C8.1.7 Committees |

|||

|

C8.1.8 Innovation |

|||

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su12176858