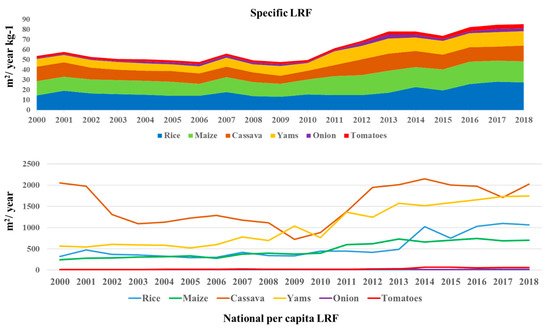

The food consumed and the household size determine the land requirement for food. Continued population growth without improved living standards and adequate food production output per hectare will further exacerbate food insecurity and land shortage in Nigeria.

- food quantity

- food expenditure

- household size

- population

- Geopolitical Zones in Nigeria

1. Introduction

Consumption of staple foods such as rice, maize and cassava is very high in low- to middle-income countries [1][2][3][4], while middle- to higher-income countries are consuming fewer staple foods and changing their consumption patterns towards more meat, processed foods and dairy products [1][5][6][7]. However, changes in dietary patterns are influenced by per capita income, lifestyle/preferences, urbanization and economic development [1][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15], resulting in a high demand for land resources [14] to cope with the diverse food consumptions. Such changes in dietary patterns are also known to increase greenhouse gas emissions, impact the climate, contribute to unbalanced dietary intake and health-related diseases, as well as further increasing pressure on ecosystem carrying capacity and land degradation [16][17][18][19][20][21][22]. Besides, the total land required for food is determined by the type of food, the quantities consumed and the size of the population [23]. Available studies state that the type of food determines the land requirement for food [23] more than the quantities of food consumed per capita [24], while others assume that the land requirement for food also depends on the yield per hectare [25]. An example of this is the fact that an average Indian diet requires less land than an average diet in the United States of America, despite the size of the population [24].

Land requirements for food have been analyzed at global, regional [26][27], country and rural levels [25][28][29][30][31] using models and thought experiments such as ALBIO (Agricultural Land use and BIOmass), the Human Appropriation of Land for Food (HALF) Index, questionnaires, household food consumption surveys, data on population, dietary habits and crop yields. Their studies concluded that our food choices affect the land used for agriculture, i.e. the land required for food depends on the type of food and the rate of change in food consumption patterns. However, this interaction is causing biodiversity to decline at an accelerating rate.

2. Food Consumption Patterns

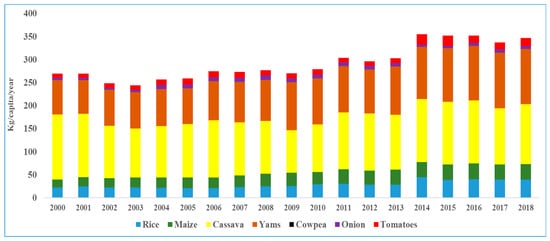

2.1. Food Consumption Patterns at the National Level

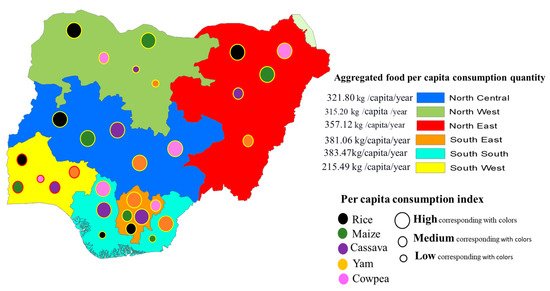

2.2. Food Consumption Patterns in the Six Geopolitical Zones

3. Findings

Food consumption patterns in the six geopolitical zones show that cereals and starchy roots contribute significantly (over 70%) to household calorie requirements. Available studies have shown that developing countries rely on starchy staple foods to meet their energy needs. For example, a similar observation was made in the city of Guyuan in Northwest China that the energy needs of the population are met by staple foods [28].

The quantity of household food consumption was estimated from household food expenditure and food prices. Therefore, the share of total household expenditure (as a proxy of income) spent on food is an indicator of household food security, and low-income households spend more of their income on providing food [32]. The Nigeria National Bureau of Statistics revealed that 59.19% was the total expenditure on food in 2019 by households in Nigeria [33].

The food consumption pattern results indicate that households are changing their dietary patterns due to their high food expenditures. This is observed in the North East and North West, indicating that the two zones are shifting their consumption patterns from rice to maize as a cheaper alternative, likewise in the South East and South South, consuming more dense calories from cassava and yam than rice and maize. Additionally, an interesting observation is that the South West consumes more cereals, especially rice, than its southern counterparts. A plausible reason for this is that the South West have more rice-producing states [34], which may have influenced the price of rice to be relatively cheaper than in other parts of the country. The North Central zones also consume more amount of cereals and starchy roots as they have the latitude to produce these crops [35].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/foods11020150

References

- Kearney, J. Food consumption trends and drivers. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 2793–2807.

- Muyanga, M.; Jayne, T.; Kodhek, G.; Ariga, J. Staple Food Consumption Patterns in Urban Kenya: Trends and Policy Implications; Tegemeo Institute of Agricultural Policy and Development, Egerton University: Nairobi, Kenya, 2005.

- Chauvin, N.D.; Mulangu, F.; Porto, G. Food Production and Consumption Trends in Sub-Saharan Africa: Prospects for the Transformation of the Agricultural Sector; UNDP Regional Bureau for Africa: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 2, p. 74.

- Ene-Obong, H.N.; Sanusi, R.A.; Udenta, E.A.; Williams, I.O.; Anigo, K.M.; Chibuzo, E.C.; Aliyu, H.M.; Ekpe, O.O.; Davidson, G.I. Data collection and assessment of commonly consumed foods and recipes in six geo-political zones in Nigeria: Important for the development of a National Food Composition Database and Dietary Assessment. Food Chem. 2013, 140, 539–546.

- Savige, G.S.; Crawford, D.; Worsley, A.; Ball, K. Food intake patterns among Australian adolescents. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 16, 738–747.

- Rivera, J.Á.; De Cossío, T.G.; Pedraza, L.S.; Aburto, T.C.; Sánchez, T.G.; Martorell, R. Childhood and adolescent overweight and obesity in Latin America: A systematic review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 321–332.

- Partearroyo, T.; Samaniego-Vaesken, M.D.L.; Ruiz, E.; Aranceta-Bartrina, J.; Gil, Á.; González-Gross, M.; Ortega, R.M.; Serra-Majem, L.; Varela-Moreiras, G. Current food consumption amongst the spanish anibes study population. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2663.

- Cao, L.J.; Tian, W.-M.; Wang, J.-M.; Malcolm, B.; Liu, H.-B.; Zhou, Z.-Y. Recent Food Consumption Trends in China and Trade. Australas. Agribus. Rev. 2013, 21, 15–44.

- Akram, W.; Henneberry, S. Consumption Patterns of Urban Punjab of Pakistan: Evidence from HIES 2013–2014. In Proceedings of the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association Annual Meeting, Boston, MA, USA, 31 July–2 August 2016.

- Galbete, C.; Nicolaou, M.; Meeks, K.A.; De Graft-Aikins, A.; Addo, J.; Amoah, S.K.; Smeeth, L.; Owusu-Dabo, E.; Klipstein-Grobusch, K.; Bahendeka, S.; et al. Food consumption, nutrient intake, and dietary patterns in Ghanaian migrants in Europe and their compatriots in Ghana. Food Nutr. Res. 2017, 61, 1341809.

- Streeter, J.L. Socioeconomic factors affecting food consumption and nutrition in China: Empirical evidence during the 1989–2009 period. Chin. Econ. 2017, 50, 168–192.

- Song, F.; Cho, M.S. Geography of food consumption patterns between South and North China. Foods 2017, 6, 34.

- Mottaleb, K.A.; Rahut, D.B.; Kruseman, G.; Erenstein, O. Changing food consumption of households in developing countries: A Bangladesh case. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2018, 30, 156–174.

- Sharma, R.; Nguyen, T.T.; Grote, U. Changing consumption patterns—Drivers and the environmental impact. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4190.

- Saleem, S.B.; Ali, Y. Effect of lifestyle changes and consumption patterns on environmental impact: A comparison study of Pakistan and China. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2019, 17, 113–122.

- Razack, N.; Ludin, A. Ecological footprint and food consumption in Minna, Nigeria. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2014.

- Akerele, D. Household food expenditure patterns, food nutrient consumption and nutritional vulnerability in Nigeria: Implications for policy. J. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2015, 54, 546–571.

- Ranganathan, J.; Vennard, D.; Waite, R.; Searchinger, T.; Dumas, P.; Lipinski, B. Shifting diets: Toward a sustainable food future. In Global Food Policy Report; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- Ray, S.; Bhattacharyya, B. A statistical investigation on analysis of food consumption pattern in India. J. Crop Weed 2016, 12, 47–54.

- Zhen, L.; Du, B. Ecological Footprint Analysis Based on Changing Food Consumption in a Poorly Developed Area of China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1323.

- Ecker, O. Agricultural transformation and food and nutrition security in Ghana: Does farm production diversity (still) matter for household dietary diversity? Food Policy 2018, 79, 271–282.

- Yin, J.; Yang, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, T.; Hao, Y.; Cui, S.; Chen, Y. Diet shift: Considering environment, health and food culture. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 719, 137484.

- Gerbens-Leenes, W.; Nonhebel, S. Food and land use. The influence of consumption patterns on the use of agricultural resources. Appetite 2005, 45, 24–31.

- Alexander, P.; Brown, C.; Arneth, A.; Finnigan, J.; Rounsevell, M.D.A. Human appropriation of land for food: The role of diet. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2016, 41, 88–98.

- Gerbens-Leenes, P.W.; Nonhebel, S.; Ivens, W.P.M.F. A method to determine land requirements relating to food consumption patterns. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2002, 90, 47–58.

- Wirsenius, S.; Azar, C.; Berndes, G. How much land is needed for global food production under scenarios of dietary changes and livestock productivity increases in 2030? Agric. Syst. 2010, 103, 621–638.

- Kastner, T.; Rivas, M.J.I.; Koch, W.; Nonhebel, S. Global changes in diets and the consequences for land requirements for food. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6868–6872.

- Zhen, L.; Cao, S.; Cheng, S.; Xie, G.; Wei, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, F. Arable land requirements based on food consumption patterns: Case study in rural Guyuan District, Western China. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1443–1453.

- Das, K.; Nonhebel, S. A comparative study of the land required for food and cooking fuel in rural India. Agric. Syst. 2019, 176, 102682.

- Kastner, T.; Nonhebel, S. Changes in land requirements for food in the Philippines: A historical analysis. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 853–863.

- Hoff, M.; De Boer, H.J. A Question-Based Method to Calculate the Human Appropriation of Land for Food (HALF) Index. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10597.

- INDDEX. International Dietary Data Expansion Project. In Data4Diets: Building Blocks for Diet-related Food Security Analysis; Tufts University: Boston, MA, USA, 2018.

- NBS, Nigeria Bureau of Statistics. 2019 Poverty and Inequality in Nigeria Report; NBS, Nigeria Bureau of Statistics: Lagos, Nigeria, 2019.

- Osabuohien, E.S.; Okorie, U.E.; Osabohien., R.A. Rice Production and Processing in Ogun State, Nigeria: Qualitative Insights from Farmers’ Association; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018.

- Agada, M.; Igbokwe, E. Influence of Food Culture and Practices on Household Food Security in North Central Nigeria. J. Food Secur. 2016, 4, 36–41.

- Ismaila, U.; Gana, A.S.; Tswanya, N.M.; Dogara, D. Cereals production in Nigeria: Problems, constraints and opportunities for betterment. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2010, 5, 1341–1350.

- Qian, L.; Li, F.; Liu, H.; Wang, L.; McCarthy, B.; Jin, S. Rice vs. Wheat: Does staple food consumption pattern affect food waste in Chinese university canteens? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 176, 105902.