Authors analyzed the mechanism and the process of fungal-induced agarwood formation in Aquilaria sinensis and studied the functional changes in the xylem structure after the process. The microscopic structure of the white zone, transition zone, agarwood zone, and decay zone xylem was studied. The distribution of nuclei, starch grains, soluble sugars, sesquiterpenes, fungal propagules, and mycelium in xylem tissues was investigated by histochemical analysis. The results show that the process of agarwood formation was accompanied by apoptosis of parenchyma cells such as interxylary phloem, xylem rays, and axial parenchyma. Regular changes in the conversion of starch grains to soluble sugars, the production of sesquiterpenoids, and other characteristic components of agarwood in various types of parenchyma cells were also observed. The material transformation was concentrated in the interxylary phloem, providing a structural and material basis for the formation of agarwood. It is the core part of the production of sesquiterpenoids and other characteristic products of agarwood.

1. Introduction

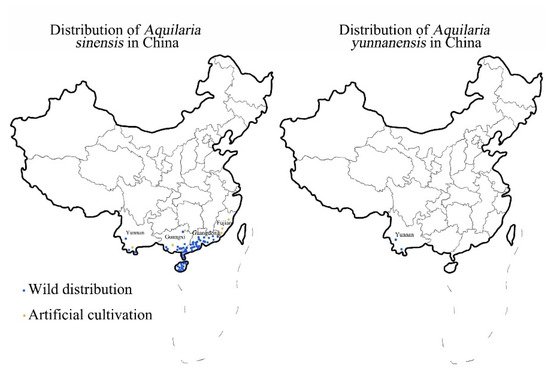

The native species of

Aquilaria trees in China are

Aquilaria sinensis and

Aquilaria yunnanensis [1], the distribution of which is shown in

Figure 1. Compared with

A. yunnanensis,

A. sinensis has a larger distribution area and stronger adaptability to the climate

[2], making it the most common tree in China for agarwood production. There is a great demand for agarwood because of its medicinal and aromatic properties which have led to the predatory logging of wild resources.

A. sinensis was included in the List of National Key Protected Wild Plants in 1999 and listed as a Class II endangered plant in China

[3]. All

Aquilaria species are listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora

[4]. There are only 130,000 wild

A. sinensis plants left, and the annual production of natural agarwood is 118 tons, accounting for only 23.6% of the market demand. Due to the scarcity of naturally occurring agarwood, artificial techniques have been effective for increasing the production of agarwood and meeting market demands

[5]. The differences between artificial agarwood and natural agarwood are mainly in the types and relative contents of sesquiterpenoids and 2-(2-phenylethyl) chromones. Short-term formation of artificial agarwood and natural agarwood formed over the years is still a certain gap but has been able to meet the national standards and enough to apply in production. Due to the rarity and high cost of natural agarwood, almost all of the agarwood currently for medicine, daily use, and spices is artificial agarwood. It can be seen that artificial agarwood has been able to replace natural agarwood to a certain extent.

Figure 1. Distribution of A. sinensis and A. yunnanensis in China.

Agarwood-inducing techniques can be divided into physical trauma, chemical induction, and biological induction methods depending on the treatment method. The physical trauma method refers to cutting and burning, which are more traditional, less efficient, and uncontrollable. Chemical induction methods include ordinary chemical methods, such as injecting inorganic salts and other chemicals that can promote the formation of agarwood, and whole-tree agarwood-inducing techniques (Agar-Wit)

[6][7]. There are drawbacks with both methods, such as complicated operation processes, chemical residues, and unstable quality

[8][9][10]. Biological induction methods usually refer to fungus induction technology, in which mycelium or fungal endophyte culture supernatants gathered from the agarwood-containing

A. sinensis that produces agarwood is inoculated into a healthy

A. sinensis trunk

[6][7][11][12]. The quality of agarwood produced by fungus induction is comparable to that of naturally occurring agarwood

[13]. At present, biological induction methods are widely used in production and have a greater prospect of development. However, the quality of agarwood obtained from different culture conditions and different strain treatments vary greatly

[14]. Moreover, characteristic agarwood components such as baimuxinal and α-copaen-11-ol were lower than those of the physical trauma method

[15], whereas the requirements for the operating environment and operating techniques were higher. The current

A. sinensis plantations usually use traditional agarwood techniques, such as physical and chemical agarwood methods, that generally require older trees (generally more than ten years) with labor-intensive operation and low yield, and some methods even produce chemical pollution and other problems. Therefore, artificial agarwood cannot form large-scale industrialization at present.

In recent years, many studies have been conducted on the structural and functional changes in the xylem of

A. sinensis during fungal infection-induced agarwood by histochemical analysis, scanning electron microscopy and transmission electron microscopy. It was found that all physiological metabolic activities of

A. sinensis, including agarwood formation, were mainly performed by parenchyma cells. The parenchyma cells in the xylem of

A. sinensis include interxylary phloem, xylem rays, and axial parenchyma. The various types of parenchyma cells form a network of living cells in the wood

[16]. Agarwood first appears in the parenchyma cells and then enters the surrounding vessels and wood fibers

[17]. Although the interxylary phloem, xylem rays, and axial parenchyma are all parenchyma cells that can store and transport and are capable of respiration and metabolism, they have different physiological functions

[18][19][20]. The interxylary phloem of

A. sinensis xylem differentiates into meristem tissue when subjected to external stimuli and cornifies the cells in the middle of the interxylary phloem, initiating the physical defense process

[21][22]. Axial parenchyma is important to the distribution of nutrients, thickens the cytoderm defensively under external stress, and produces agarwood

[23][24].

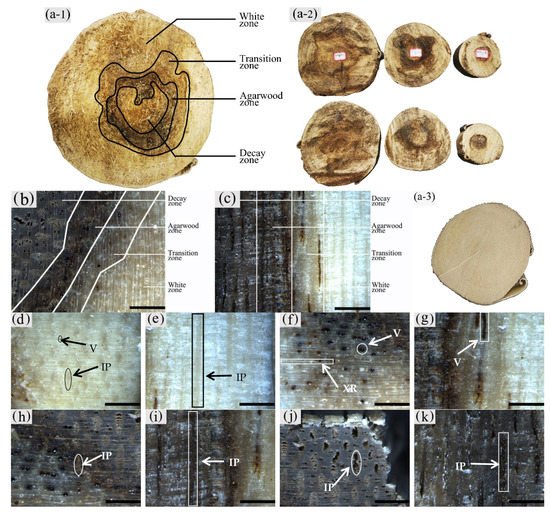

2. Macrostructural Differences at Different Zones of the Xylem

The sapwood of uninoculated A. sinensis was white and without an aromatic smell as shown in Figure 2(a-3). After agarwood formation, the black-brown pathological heartwood was produced, which had a greasy luster and a distinct agarwood odor. The central part of the xylem where agarwood production began could be divided radially into four different zones, from outside to inside: the white zone, transition zone, agarwood zone, and decay zone from outside to inside (Figure 2a–c). The wood slices collected at 20 cm above the roots, the diameter at breast height, and the branching point were as Figure 2(a-2). The main differences between zones were color, odor, and the distribution and morphology of parenchyma cells and vessels.

Figure 2. Macrostructure of the xylem of A. sinensis. (a-1,a-2) Different zones of air-dried timber in transverse surface. (a-3) blank control without being inoculated. (b) Different zones in transverse surface. (c) Different zones in radial surface. (d) Transverse surface of white zone. (e) Radial surface of white zone. (f) Transverse surface of transition zone. (g) Radial surface of transition zone. (h) The dark part is the transverse surface of agarwood zone. (i) The dark part is the radial surface of agarwood zone. (j) Transverse surface of decay zone. (k) Radial surface of decay zone. V: vessel; IP: interxylary phloem; XR: xylem ray. Scale bars = (a) 100 mm; (b–k) 400 μm.

It was observed that the macrostructural of the white zone was similar to that of the blank control. The white zone was the outside area of the xylem without agarwood formation, where the wood color was white, and it did not have an aroma (Figure 2d,e). The transition zone was the area near the white zone, usually 5–10 mm wide, where an aromatic fragrance was first detected. The interxylary phloem was light brown to dark brown, the xylem ray was white to light brown, and the color of all tissues tended to deepen from the outside to the inside. The vessels with a distinct greasy luster were visible on the transverse surface (Figure 2f). The axial parenchyma was not noticeable on the radial surface; however, vessels filled with grease-like inclusions were observed. The agarwood zone had the main accumulation of agarwood. It was located on the inner side of the transition zone, usually 10–25 mm wide. It had a distinct odor and was dark brown to black in color. On the transverse surface, the yellowish-brown interxylary phloem and its adjacent xylem rays could be observed with the naked eye (Figure 2h), whereas the dark striped vessels and interxylary phloem were seen on the radial surface (Figure 2i). The decay zone was the innermost region of the xylem, without a noticeable odor or greasy sheen. It was typically light to dark brown in color with loose and fragile wood. The cavity-like interxylary phloem was visible to the naked eye on the transverse surfaces, and the xylem rays remained intact (Figure 2j). On the transverse surface, there were banded interxylary phloem and disconnected vessels, both of which were cavity-shaped (Figure 2k).

As shown in Figure 2(a-2) that compares the agarwood formation and stratification of the wood slices at different heights, the wood slices at the branching point just started to form agarwood, while the agarwood zone was located in the middle of the wood slices, and this was a small area of decay zone. At the breast diameter and the ground diameter, the agarwood zone expands outward, and the area of the decay zone increases. It can be seen that the agarwood was first produced in the pith of the tree, combined with the wood of the xylem to form the agarwood zone, and spread outward as the agarwood form.

The macroscopic structure of the xylem of A. sinensis inoculated for 12 and 18 months differed. In terms of zoning characteristics, the decay zone of A. sinensis with 12 months of inoculation was lighter in color, usually light yellow-brown, and the agarwood zone had a similar width with a distinct transitional zone and a wider white zone.

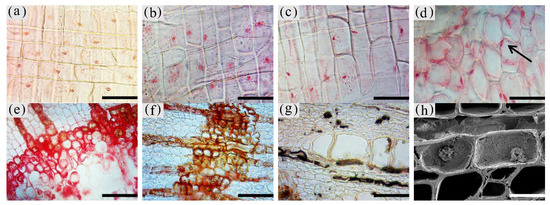

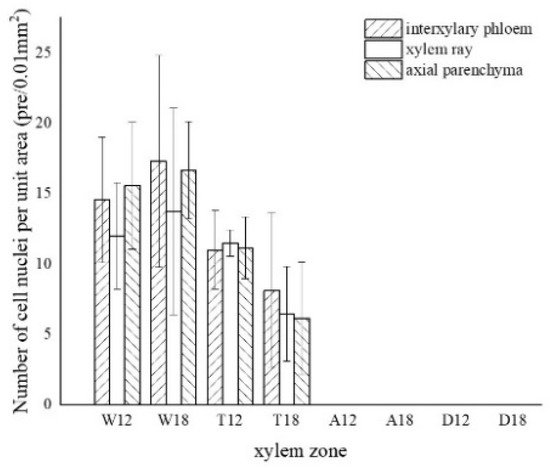

3. Observation on the Nucleus of Parenchyma Cells in the Xylem of A. sinensis

The morphology of the nuclei in different zones of the xylem is shown in Figure 3, and the statistics are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3. Color development of the nuclei of parenchyma cells in the xylem of A. sinensis. (a) Nuclei in the blank control. (b) Nuclei in the medialis xylem rays of the white zone. (c) Nuclei in the xylem rays of the transition zone. (d) Nuclei in the interxylary phloem of the transition zone. (e) Medialis of transitional zone transverse surface without the nucleus. (f) No nuclei were observed in the agarwood zone. (g) No nuclei were observed in the decay zone. (h) Highly crumpled nuclei in the transition zone. Scale bars = (a–d) 50 μm; (e–g) 80 μm; (h) 25 μm.

Figure 4. Variation in the number of nuclei in a different zone of cells. W—white zone; T—transition zone; A—agarwood zone; D—decay zone; 12—inoculated for 12 months; 18—inoculated for 18 months.

The nuclei in the white zone were full and rounded and were mainly distributed in the parenchyma cells which were similar to the nuclei of the blank control (as in Figure 3a). The average number of nuclei in the white zone was 14.98 nuclei/10−2 mm2. The highest number of nuclei was in the axial parenchyma, approximately 16.13 nuclei/10−2 mm2, followed by the interxylary phloem with approximately 15.95 nuclei/10−2 mm2. The lowest number of nuclei was in the xylem rays, approximately 12.87 nuclei/10−2 mm2. On the radial surface, there were more nuclei in the xylem rays near the cambium, but they gradually decreased closer to the pith. The micrograph of xylem rays on the outside of the white zone shows that nuclei were present in each cell and were more rounded, as shown in Figure 3b. The micrograph of the xylem rays on the inside of the white zone is shown in Figure 3c, with no nuclei in some cells and fewer nuclei overall than the outer white zone, and the nuclei started to crumple and became oval. Nuclei were observed in a few xylem rays and interxylary phloem in the transition zone. They were usually pyknotic and close to the cell wall (Figure 3d at the arrow). They were considerably crinkled, as observed by SEM (Figure 3h). No nuclei were observed in the inner part of the transition zone near the agarwood zone (Figure 3e). The number of nuclei in the transitional zone was less than that in the white zone, with an average of 9.06 nuclei/10−2 mm2. The highest number of nuclei in the interxylary phloem was approximately 9.57 nuclei/10−2 mm2, followed by the xylem rays at about 8.97 nuclei/10−2 mm2. The lowest number of nuclei was in the axial parenchyma, approximately 8.64 nuclei/10−2 mm2. Cells of interxylary phloem and xylem rays in the agarwood zone were stained as a whole, and no nuclei were observed (Figure 3f). There was no discoloration in any cells in the decay area (Figure 3g). Nuclei were found to be more abundant in 18 months than 12 months of inoculation, with the greatest number in the interxylary phloem, whereas 12 months of inoculation was mainly distributed in the axial parenchyma.

4. Distribution of Sugars in the Xylem of A. sinensis

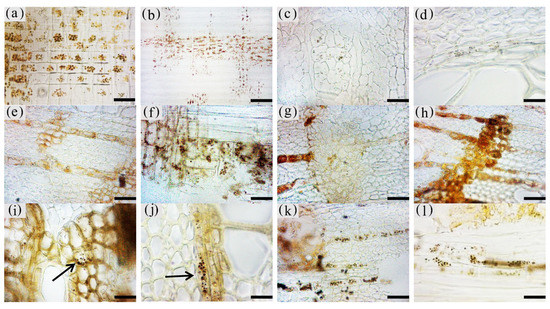

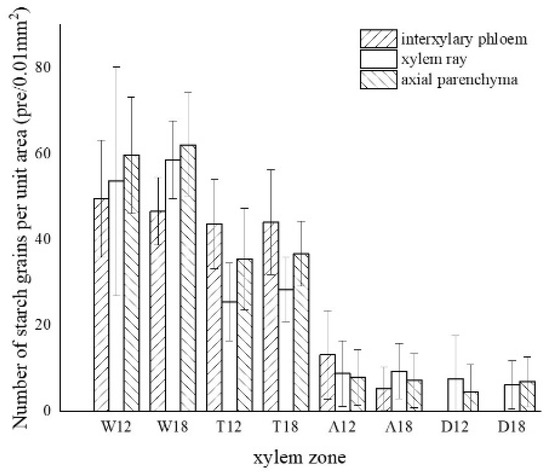

The morphology of starch grains in different zones of xylem is shown in Figure 5, and the statistics are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 5. Color development of starch grains in xylem parenchyma cells of A. sinensis. (a) Starch grains in the blank control. (b) Starch grains in axial parenchyma and xylem rays in radial surface of white zone. (c) Starch grains in the interxylary phloem in the transverse surface of the white zone. (d) Starch grains in the medical wood rays in the transverse surface of the white zone. (e) Starch grains in the interxylary phloem in the transverse surface of the transition zone. (f) Some of the xylem rays and axial parenchyma in the radial surface of the transition zone contain starch grains. (g) No starch grains in the medialis of the interxylary phloem in transition zone. (h) Most parenchyma cells without starch grains in the transverse surface of the agarwood zone. (i) Starch grains in some of the interxylary phloem in the transverse surface of the agarwood zone. (j) Starch grains in some of the interxylary phloem in the transverse surface of the agarwood zone. (k) Starch grains in some of the interxylary phloem in the transverse surface of the decay zone. (l) Starch grains in some of the interxylary phloem in the radial surface of the decay zone. Scale bars = (c,e–i,k,l) 50 μm; (b)200 μm; (a,d,j) 25 μm.

Figure 6. Statistics of color development of starch grains in parenchyma cells. W—white zone; T—transition zone; A—agarwood zone; D—decay zone; 12—inoculated for 12 months; 18—inoculated for 18 months.

The starch grains in the blank control were mainly distributed in the xylem rays, axial parenchyma, and interxylary phloem, which were rounded and more densely distributed (Figure 5a). In the white zone, starch grains were concentrated in the xylem rays and axial parenchyma, which were similar to the blank control, with an average of approximately 55.04 grains/10−2 mm2. The starch grains in the xylem rays were arranged more closely and a noticeable group-like arrangement was observed, with approximately 56.13 grains/10−2 mm2. The distribution of starch grains in the axial parenchyma and interxylary phloem were more scattered and arranged in a striped pattern (Figure 5b,c), with approximately 60.91 grains/10−2 mm2 and 48.08 grains/10−2 mm2, respectively. The number of starch grains in the xylem rays of the white zone gradually decreased from the outside to the inside, as shown in Figure 5d. The number of starch grains in the transition zone was significantly reduced, with an average number of 35.62 grains/10−2 mm2. The starch grains were mainly distributed in xylem rays, axial parenchyma, and interxylary phloem, where the majority were in the interxylary phloem, approximately 43.85 grains/10−2 mm2 (Figure 5e). The axial parenchyma contained approximately 36.09 grains/10−2 mm2, and the number of wood ray starch grains was the lowest with approximately 26.93 grains/10−2 mm2 (Figure 5f). In this region, the number of starch grains gradually decreased from the outside to the inside, with almost no starch grains observed in the area near the agarwood zone (Figure 5g). The agarwood zone contained an average of 8.62 grains/10−2 mm2; however, most of the parenchyma cells had no starch grains (Figure 5h). The interxylary phloem contained the largest amount of starch grains with approximately 9.21 grains/10−2 mm2, which were smaller in size but more densely distributed (Figure 5i). The xylem rays were more scattered and mainly distributed at the cell edges (Figure 5j), with approximately 9.09 grains/10−2 mm2. The axial parenchyma had the lowest grain concentration with approximately 7.56 grains/10−2 mm2. There were more starch grains in the 18 months of inoculation in the decay zone than in the 12 months of inoculation, and both had a similar distribution pattern in different zones. In the decay zone, very small amounts of starch grains could still be observed, almost entirely in the xylem rays (Figure 5k) and in the axial parenchyma (Figure 5l), with an average number of 6.80 grains/10−2 mm2 and 7.98 grains/10−2 mm2, respectively, and not found in the intrinsic siliques.

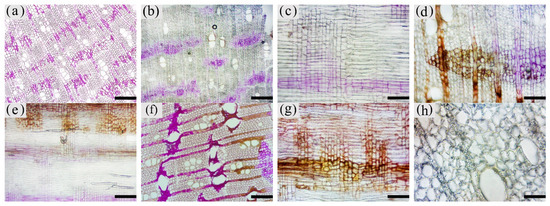

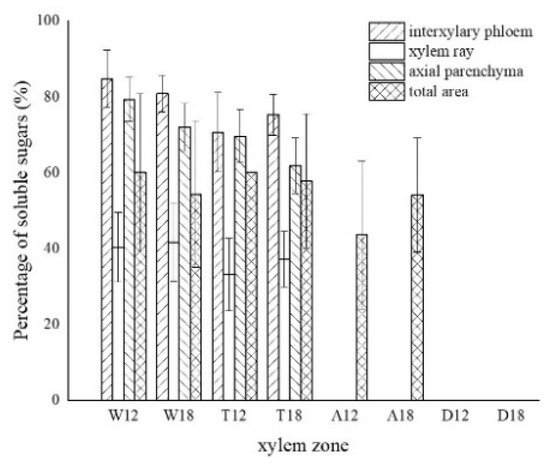

The soluble sugars staining in different compartments of the xylem is shown in Figure 7. The statistics are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 7. Color development of soluble reducing sugars in xylem parenchyma cells of A. sinensis. (a) Transverse surface of blank control. (b) Transverse surface of white zone. (c) Radial surface of white zone. (d) Transverse surface of transition zone. (e) Radial surface of transition zone. (f) Transverse surface of agarwood zone. (g) Radial surface of agarwood zone. (h) Transverse surface of decay zone. Scale bars= (a,b,e,f) 200 μm; (c,d,g) 100 μm; (h) 50 μm.

Figure 8. Statistics of color development of soluble sugar in xylem parenchyma cells. W—white zone; T—transition zone; A—agarwood zone; D—decay zone; 12—inoculated for 12 months; 18—inoculated for 18 months.

The distribution of soluble sugars in the blank control is shown in Figure 7a. The soluble sugars in the white zone were mainly distributed in the axial parenchyma and the interxylary phloem and less in the xylem rays. It was similar to the distribution in the blank control. Approximately 82.82% of the interxylary phloem was purplish-red in the transverse surface (Figure 7b), and approximately 75.68% of the axial parenchyma was stained purplish-red in the radial surface (Figure 7c). The xylem rays were only purplish-red near the interxylary phloem, with a color development rate of approximately 40.99%. In the transition zone, the colored area of the interxylary phloem and axial parenchyma was larger, whereas a small portion of the xylem rays was purplish-red and lighter in color. The purplish-red interxylary phloem was observed on the transverse surface (Figure 7d) with a colored area of approximately 72.98%. The purplish-red axial parenchyma could be observed in the radial surface (Figure 7e) with a colored area of approximately 65.75%. The colored area in the xylem rays was less than 35.16%. Some cells in the agarwood zone were purplish-red, as shown in Figure 7f,g. No noticeable pattern was observed in the distribution of soluble sugars in this zone. They were present in various cells and not restricted to parenchyma cells. The colored area was approximately 48.85% of the total area. No discoloration of parenchyma cells was observed in the decay areas (Figure 7h). The soluble sugar content of the 18 months of inoculation in A. sinensis was less than that of the 12 months of inoculation.

An insignificant amount of starch grains was observed in the decay zone, which is inconsistent with the results of previous studies

[16]. Starch grains were typically located in the outer xylem rays of the decay zone. A likely reason for this is that the companion cells with metabolic functions and the sieve tubes with transport functions in interxylary phloem were blocked by agarwood resin and subsequently died due to insufficient supply of nutrients

[21], while the parenchyma cells lost their ability to transport and break down sugar substances such as starch. This process accelerated when there were reduced amounts of unmetabolized starch grains in the parenchyma cells, which could not be metabolized to soluble sugars or transported and had to be temporarily retained in the resin-filled parenchyma cells. As the xylem decayed deeper, this area became the decay zone with the agarwood resin loss. These starch grains gradually decomposed into nutrients for fungi. Thus, the center of the decay zone contained no starch grains. The SEM results for the parenchyma cells of the decay zone supported this hypothesis. The cell walls of the parenchyma cells in the decay zone were covered with inclusions, which blocked the channels for intercellular material transport, such as the starch grain. A negligible amount of incompletely decomposed starch grains was observed in this zone.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/f13010043