Despite some successes of selective anti-BRAFV600E inhibitors, resistance remains a major challenge. The aim of our study is to determine the role of nuclear BRAFV600E and its newly identified partner, HMOX1, in melanoma aggressiveness and drug resistance.

- melanoma

- HMOX-1

- nuclear BRAFV600E

- aggressiveness

- vemurafenib resistance

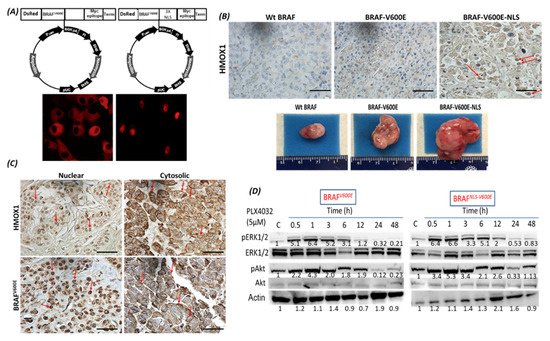

[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42]1. Translocation of BRAFV600E into the Nucleus Upregulates HMOX-1 Expression in Melanoma Cell Lines

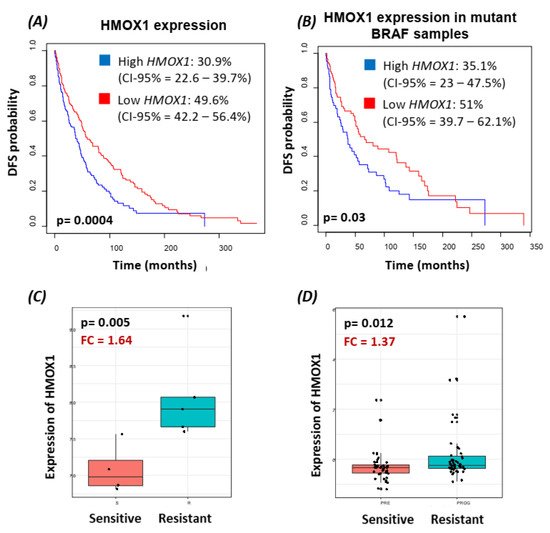

2. HMOX-1 Gene Expression Is Associated with an Aggressive Phenotype, a Worse Prognosis, and Resistance to BRAF Inhibitor

3. Translocation of BRAFV600E to the Nucleus Promotes HMOX-1 Upregulation in a Xenograft Mouse Model of Melanoma

4. The Localization of BRAFV600E and HMOX-1 in Human Melanoma Samples

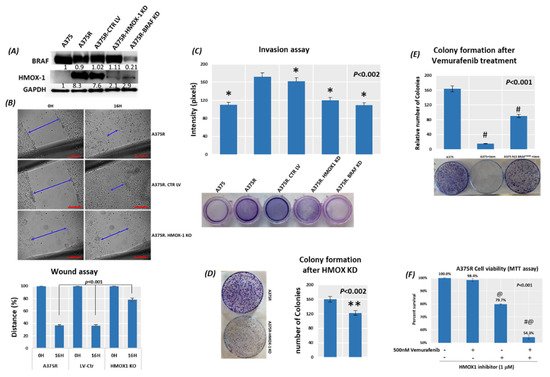

5. Suppression of HMOX-1 Has an Anti-Proliferative Effect in Resistant Melanoma Cells

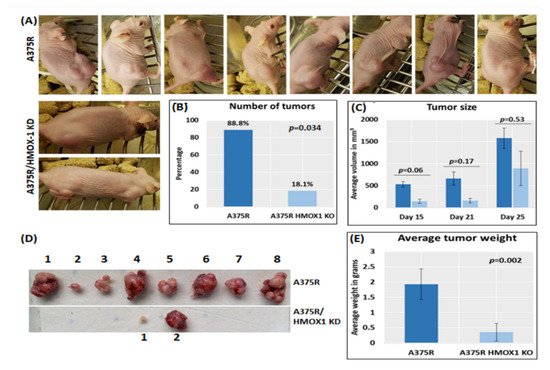

6. Suppression of HMOX-1 Reduces the Number and Size of Tumors in a Preclinical Melanoma Model

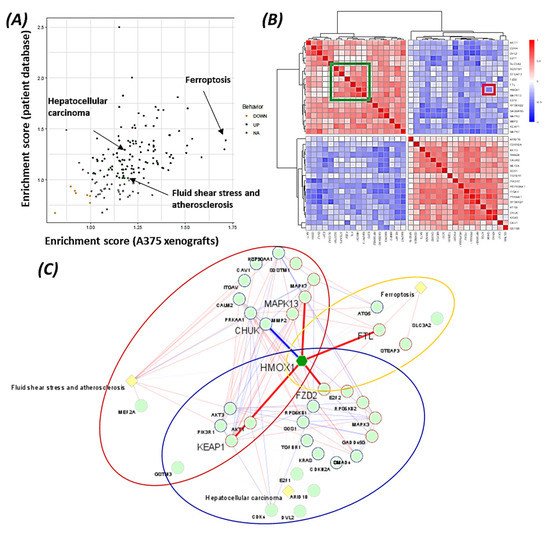

7. Pathways Analysis Revealed the Functional Role of HMOX1 in the BRAF Inhibitor Resistance Process

The data suggest that HMOX-1 actively participates in BRAF inhibitors’ resistance process, linking different signaling pathways that are known to be involved in therapy resistance (PI3K, MAPK, TGF-beta, and Wnt pathways).

-

Discussion

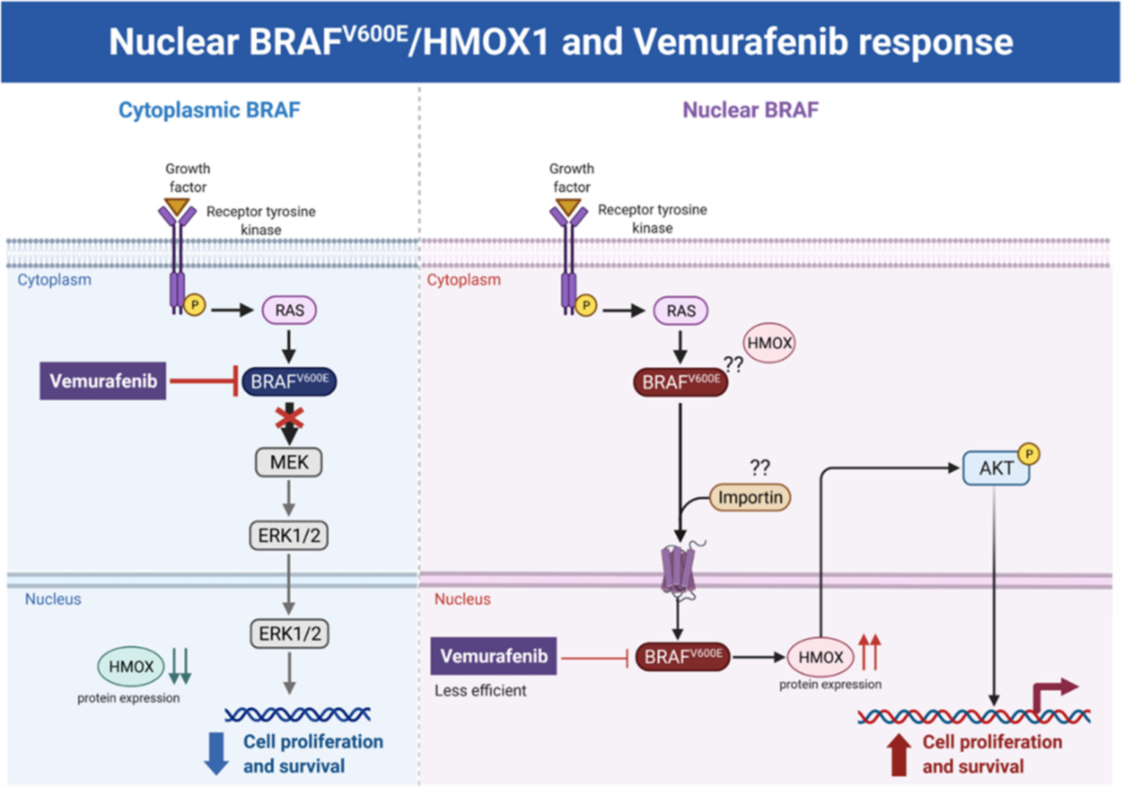

BRAF is a proto-oncogene (also known as v-raf murine sarcoma viral homolog B1) that belongs to the Raf kinase family [28]. BRAFV600E mutations are linked with several types of tumors, where they activate the MAPK signaling pathway constitutively, resulting in uncontrolled cell proliferation and survival [29]. Transport across cell compartments is required for functional regulation and for diversity in the cell, but aberrant nucleocytoplasmic trafficking has been implicated in cancers such as thyroid, melanoma, and others [30–33]. We reported for the first time in our previous study [24] a strong association between nuclear BRAFV600E expression and aggressive clinicopathologic features, including overall stage, tumor stage, lymph node metastasis, depth of invasion, Clark level, mitotic activity, and ulceration. In the same study, we reported that the SkMel-28 cell line (BRAFV600E) displays a dynamic nuclear localization of BRAFV600E, regulated by the removal or addition of FBS or epidermal growth factor (EGF) to the media. In contrast, and as we report in the current study (Figure S11), WT BRAF does not show any nuclear localization by immunofluorescence in the SKMel-202 melanoma cell line. In the literature, two studies mentioned a small fraction of WT BRAF in the nucleus. In the first study, an exogenous truncated BRAF transfected in NIH3T3 cells was used, and this artificial system cannot be generalized or applied to the endogenous BRAF. In the second study, Shin et al. used a non-cancer C2C12 myoblast cell line and found a very tiny fraction of WT BRAF in the nucleus compared to a strong nuclear presence of BRAFV600E [34,35]. Our hypothesis is that WT BRAF activation requires external growth factors, and its localization is totally cytoplasmic. The constitutively active BRAFV600E is independent of external stimulus, and the nuclear localization may provide the BRAFV600E with a sheltering mechanism against inhibitors, possibly through a novel and unexpected collaboration with overexpressed HMOX1. However, mechanistic studies are required for the validation and explanation of our previous findings. In this study, we report that A375R melanoma vemurafenib-resistant cells display a nuclear localization of BRAFV600E after synchronization and stimulation with the FBS. A 10-fold upregulation of HMOX-1 protein is observed in A375R cells with nuclear localization of BRAFV600E compared to A375 parental cells that have cytoplasmic BRAFV600E. Surprisingly, HMOX1 upregulation in A375R or WM983C cell lines is not the consequence of NRF2 protein overexpression (Figure S7). In another study, it was hypothesized that the existence of a possible HMOX-1 reserve in the form of mRNA to be transformed into protein when necessary [36]. Additionally, we show that HMOX-1 upregulation crucially limits the efficacy of the BRAF inhibitor PLX4032 and is important in promoting cell viability and aggressiveness. Our results provide the first evidence that nuclear BRAFV600E plays a critical role in the regulation of HMOX-1 protein overexpression in resistant melanoma cells. A recent study with a WT BRAF cell line (MeWO) showed neither basal expression nor induction of HMOX-1 after treatment with PLX4032 [37]. HMOX-1 is one of the most important mechanisms of cell adaptation to stress, and chemoand radiotherapy both fundamentally stimulate HMOX-1 expression [38]. However, the transcriptional or post-transcriptional mechanisms controlling HMOX-1 expression in response to cytotoxic stress remain elusive. This study extends our understanding by identifying nuclear BRAFV600E as a potential player in HMOX-1 expression. The nuclear translocation and the molecular mechanism of nuclear BRAFV600E in promoting tumor progression and resistance is still poorly understood. Thus, to the best of our knowledge, the present study provides the first evidence of a possible role of nuclear BRAFV600E/HMOX-1/ AKT in melanoma resistance. Figure 7 is a hypothetical model of how melanoma cells with nuclear BRAF and high HMOX-1 expression can activate the AKT pathway and resist vemurafenib treatment.

Using bioinformatics analysis, we determined a relationship between HMOX-1 upregulation and disease-free survival (DFS). Indeed, patients with high HMOX-1 have a 19% lower chance of survival after five years than patients with lower HMOX-1 expression. The resistance to BRAFV600E inhibitors is also correlated with the high expression of HMOX-1 in a melanoma mouse model and in a melanoma patient database.To further corroborate our bioinformatics results, cells expressing nuclear and cytoplasmic BRAFV600E were subcutaneously injected into nude mice. Nuclear BRAFV600E cells were able to induce more HMOX-1 protein expression and phosphorylated Akt than cells harboring cytoplasmic BRAFV600E. Following the same pattern, the human metastatic melanoma cores expressed more nuclear HMOX-1 when BRAFV600E was detected in the nucleus. This nuclear HMOX-1 expression in nuclear BRAFV600E cores was more prevalent in metastatic malignant melanoma specimens. Remarkably, the intranuclear localization of the kinase raised the resistance of melanoma cells to drug therapy, and this was supported by reactivation of the Akt pathway as an alternative pathway for cell survival. Thus, targeting mediators of Akt activation could be a possible option for intervening with drug resistance in metastatic melanoma [39]. To address whether HMOX-1 reduction could interfere with melanoma aggressiveness, compromised HMOX-1 cell lines have been established and are correlated with melanoma-decelerated cell proliferation and invasion rate along with slower colony formation. Furthermore, an in vivo study showed a significant decrease in the number, size, and weight of tumors after knocking down HMOX-1. Remarkably, the A375 sensitive cells developed resistance when expressing NLS-BRAFV600E. Interestingly, the pathway analysis showed that ferroptosis is highly associated with HMOX-1 expression. Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent cell death process characterized by the accumulation of lipid peroxides and is genetically and biochemically different from apoptosis. It is worth noting that nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (NRF2) activation and the subsequent deregulation of iron signaling in cancers have been implicated in cancer development. Constitutive NRF2 activation and NRF2-dependent upregulation of the iron storage protein ferritin (FTL) or HMOX-1 can lead to enhanced proliferation and therapy resistance [40–42].

Figure 7. Hypothetical model of the melanoma resistance to vemurafenib. Melanoma cells with cytoplasmic BRAFV600E and low HMOX-1 expression are more sensitive to vemurafenib treatment than cells with nuclear BRAFV600E, high HMOX-1 expression, and an activated AKT pathway.

-

Conclusions

In conclusion, there is increasing interest in a possible means of inhibiting HMOX-1 expression in order to improve the sensitivity of cancer cells to BRAFV600E inhibitors. In this context, the nuclear BRAFV600E/HMOX-1/AKT axis is associated with melanoma aggressiveness. The cytoplasmic BRAFV600E expression had a modest effect in promoting HMOX-1 overexpression and was not correlated with advanced disease. Therefore, the combination of specific HMOX-1 inhibitors with BRAFV600E inhibitors is anticipated to reduce melanoma aggressiveness and improve BRAFV600E inhibitor-based therapies.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers14020311

References

- Rozeman, E.A.; Dekker, T.; Haanen, J.B.A.G.; Blank, C.U. Advanced Melanoma: Current Treatment Options, Biomarkers, and Future Perspectives. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2017, 19, 303–317

- Davies, H.; Bignell, G.R.; Cox, C.; Stephens, P.; Edkins, S.; Clegg, S.; Teague, J.;Woffendin, H.; Garnett, M.J.; Bottomley,W.; et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 2002, 417, 949–954

- Maurer, G.; Tarkowski, B.; Baccarini, M. Raf kinases in cancer–roles and therapeutic opportunities. Oncogene 2011, 30, 3477–3488.

- Haugh, A.M.; Johnson, D.B. Management of V600E and V600K BRAF-Mutant Melanoma. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2019, 20, 81.

- Flaherty, K.T.; Smalley, K.S.M. Preclinical and clinical development of targeted therapy in melanoma: Attention to schedule. Pigment. Cell Melanoma Res. 2009, 22, 529–531

- Manzini, C.; Venè, R.; Cossu, I.; Gualco, M.; Zupo, S.; Dono, M.; Spagnolo, F.; Queirolo, P.; Moretta, L.; Mingari, M.C.; et al. Cytokines can counteract the inhibitory effect of MEK-i on NK-cell function. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 60858–60871

- Moriceau, G.; Hugo,W.; Hong, A.; Shi, H.; Kong, X.; Yu, C.C.; Koya, R.C.; Samatar, A.A.; Khanlou, N.; Braun, J.; et al. Tunable-Combinatorial Mechanisms of Acquired Resistance Limit the Efficacy of BRAF/MEK Cotargeting but Result in Melanoma Drug. Addiction. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 240–256

- Khamari, R.; Trinh, A.; Gabert, P.E.; Corazao-Rozas, P.; Riveros-Cruz, S.; Balayssac, S.; Malet-Martino, M.; Dekiouk, S.; Curt, M.J.C.; Maboudou, P.; et al. Glucose metabolism and NRF2 coordinate the antioxidant response in melanoma resistant to MAPK inhibitors. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 1–14

- Ndisang, J.F. Synergistic Interaction Between Heme Oxygenase (HO) and Nuclear-Factor E2- Related Factor-2 (Nrf2) against Oxidative Stress in Cardiovascular Related Diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23, 1465–1470

- Loboda, A.; Damulewicz, M.; Pyza, E.; Jozkowicz, A.; Dulak, J. Role of Nrf2/HO-1 system in development, oxidative stress response and diseases: An evolutionarily conserved mechanism. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 3221–3247

- Pachori, A.S.; Smith, A.; McDonald, P.; Zhang, L.; Dzau, V.J.; Melo, L.G. Heme-oxygenase-1-induced protection against hypoxia/reoxygenation is dependent on biliverdin reductase and its interaction with PI3K/Akt pathway. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2007, 43, 580–592.

- Jozkowicz, A.; Was, H.; Dulak, J. Heme oxygenase-1 in tumors: Is it a false friend? Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2007, 9, 2099–2117.

- Wu,W.; Ma, D.;Wang, P.; Cao, L.; Lu, T.; Fang, Q.; Zhao, J.;Wang, J. Potential crosstalk of the interleukin-6-heme oxygenase-1-dependent mechanism involved in resistance to lenalidomide in multiple myeloma cells. FEBS J. 2015, 283, 834–849

- Zhe, N.;Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Lin, X.; Chai, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Fang, Q. Heme oxygenase-1 plays a crucial role in chemoresistance in acute myeloid leukemia. Hematology 2014, 20, 384–391

- Furfaro, A.L.; Traverso, N.; Domenicotti, C.; Piras, S.; Moretta, L.; Marinari, U.M.; Pronzato, M.A.; Nitti, M. The Nrf2/HO-1 Axis in Cancer Cell Growth and Chemoresistance. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 1958174

- Furfaro, A.L.; Piras, S.; Passalacqua, M.; Domenicotti, C.; Parodi, A.; Fenoglio, D.; Pronzato, M.A.; Marinari, U.M.; Moretta, L.;raverso, N.; et al. HO-1 up-regulation: A key point in high-risk neuroblastoma resistance to bortezomib. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2014, 1842, 613–622

- Furfaro, A.L.; Piras, S.; Domenicotti, C.; Fenoglio, D.; De Luigi, A.; Salmona, M.; Moretta, L.; Marinari, U.M.; Pronzato, M.A.; Traverso, N.; et al. Role of Nrf2, HO-1 and GSH in Neuroblastoma Cell Resistance to Bortezomib. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152465.

- Wang, T.Y.; Liu, C.L.; Chen, M.J.; Lee, J.J.; Pun, P.C.; Cheng, S.P. Expression of haem oxygenase-1 correlates with tumour aggressiveness and BRAF V600E expression in thyroid cancer. Histopathology 2015, 66, 447–456

- Mukhopadhyay, S.; Goswami, D.; Adiseshaiah, P.P.; Burgan, W.; Yi, M.; Guerin, T.M.; Kozlov, S.V.; Nissley, D.V.; McCormick, F. Undermining Glutaminolysis Bolsters Chemotherapy While NRF2 Promotes Chemoresistance in KRAS-Driven Pancreatic Cancers. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 1630–1643.

- Day, F.; Muranyi, A.; Singh, S.; Shanmugam, K.; Williams, D.; Byrne, D.; Pham, K.; Palmieri, M.; Tie, J.; Grogan, T.; et al. A mutant BRAF V600E-specific immunohistochemical assay: Correlation with molecular mutation status and clinical outcome in colorectal cancer. Target. Oncol. 2014, 10, 99–109

- Hill, R.; Cautain, B.; De Pedro, N.; Link,W. Targeting nucleocytoplasmic transport in cancer therapy. Oncotarget 2013, 5, 11–28.

- Fragomeni, R.A.S.; Chung, H.W.; Landesman, Y.; Senapedis,W.; Saint-Martin, J.R.; Tsao, H.; Flaherty, K.T.; Shacham, S.; Kauffman, M.; Cusack, J.C. CRM1 and BRAF inhibition synergize and induce tumor regression in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 24. 2013, 12, 1171–1179

- Andreadi, C.; Noble, C.; Patel, B.; Jin, H.; Hernandez, M.M.A.; Balmanno, K.; Cook, S.J.; Pritchard, C. Regulation of MEK/ERK pathway output by subcellular localization of B-Raf. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2012, 40, 67–72

- Abd Elmageed, Z.Y.; Moore, R.F.; Tsumagari, K.; Lee, M.M.; Sholl, A.B.; Friedlander, P.; Al-Qurayshi, Z.; Hassan, M.; Wang, A.R.; Boulares, H.A.; et al. Prognostic Role of BRAF(V600E) Cellular Localization in Melanoma. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2018, 226, 526–537

- Abd Elmageed, Z.Y.; Sholl, A.B.; Tsumagari, K.; Al-Qurayshi, Z.; Basolo, F.; Moroz, K.; Boulares, A.H.; Friedlander, P.; Miccoli, P.; Kandil, E. Immunohistochemistry as an accurate tool for evaluating BRAF-V600E mutation in 130 samples of papillary thyroid cancer. Surgery 2017, 161, 1122–1128

- Wang, L.; Feng, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X. DEGseq: An R package for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics 2009, 26, 136–138

- Liu, L.;Wu, Y.; Bian, C.; Nisar, M.F.;Wang, M.; Hu, X.; Diao, Q.; Nian,W.;Wang, E.; Xu,W.; et al. Heme oxygenase 1 facilitates cell proliferation via the B-Raf-ERK signaling pathway in melanoma. Cell Commun. Signal. 2019, 17, 3

- Ikawa, S.; Fukui, M.; Ueyama, Y.; Tamaoki, N.; Yamamoto, T.; Toyoshima, K. B-raf, a new member of the raf family, is activated by DNA rearrangement. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1988, 8, 2651–2654

- Sclafani, F.; Gullo, G.; Sheahan, K.; Crown, J. BRAF mutations in melanoma and colorectal cancer: A single oncogenic mutation with different tumour phenotypes and clinical implications. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 2013, 87, 55–68

- Gorlich, D.; Mattaj, I.W. Nucleocytoplasmic transport. Science 1996, 271, 1513–1518. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, M.-C.; Link,W. Protein localization in disease and therapy. J. Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 3381–3392. [CrossRef]

- Margonis, G.A.; Buettner, S.; Andreatos, N.; Kim, Y.;Wagner, D.; Sasaki, K.; Beer, A.; Schwarz, C.; Løes, I.M.; Smolle, M.; et al. Association of BRAF MutationsWith Survival and Recurrence in Surgically Treated PatientsWith Metastatic Colorectal Liver Cancer. JAMA Surg. 2018, 153, e180996

- Mor, A.; White, M.A.; Fontoura, B.M. Nuclear Trafficking in Health and Disease. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2014, 28, 28–35. [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.;Watanabe, S.; Hoelper, S.; Krüger, M.; Kostin, S.; Pöling, J.; Kubin, T.; Braun, T. BRAF activates PAX3 to control muscle precursor cell migration during forelimb muscle development. eLife 2016, 5, e18351

- Hey, F.; Andreadi, C.; Noble, C.; Patel, B.; Jin, H.; Kamata, T.; Straatman, K.; Luo, J.; Balmanno, K.; Jones, D.T.; et al. Overexpressed, N-terminally truncated BRAF is detected in the nucleus of cells with nuclear phosphorylated MEK and ERK. Heliyon 36. 2018, 4, e01065.

- Scapagnini, G.; D’Agata, V.; Calabrese, V.; Pascale, A.; Colombrita, C.; Alkon, D.; Cavallaro, S. Gene expression profiles of heme oxygenase isoforms in the rat brain. Brain Res. 2002, 954, 51–59

- Furfaro, A.L.; Ottonello, S.; Loi, G.; Cossu, I.; Piras, S.; Spagnolo, F.; Queirolo, P.; Marinari, U.M.; Moretta, L.; Pronzato, M.A.; et al. HO-1 downregulation favors BRAF V600 melanoma cell death induced by Vemurafenib/PLX4032 and increases NK recognition. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 146, 1950–1962

- Luo, X.-H.; Liu, J.-Z.; Wang, B.; Men, Q.-L.; Ju, Y.-Q.; Yin, F.-Y.; Zheng, C.; Li, W. KLF14 potentiates oxidative adaptation via modulating HO-1 signaling in castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2019, 26, 181–195

- Niessner, H.; Forschner, A.; Klumpp, B.; Honegger, J.B.;Witte, M.; Bornemann, A.; Dummer, R.; Adam, A.; Bauer, J.; Tabatabai, G.; et al. Targeting hyperactivation of the AKT survival pathway to overcome therapy resistance of melanoma brain metastases. Cancer Med. 2012, 2, 76–85

- Kerins, M.J.; Ooi, A. The Roles of NRF2 in Modulating Cellular Iron Homeostasis. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 29, 1756–1773.

- Kweon, M.-H.; Adhami, V.M.; Lee, J.-S.; Mukhtar, H. Constitutive Overexpression of Nrf2-dependent Heme Oxygenase-1 in A549 Cells Contributes to Resistance to Apoptosis Induced by Epigallocatechin 3-Gallate. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 33761–33772

- Pham, C.G.; Bubici, C.; Zazzeroni, F.; Papa, S.; Jones, J.; Alvarez, K.; Jayawardena, S.; De Smaele, E.; Cong, R.; Beaumont, C.; et al. Ferritin heavy chain upregulation by NF-kappaB inhibits TNFalpha-induced apoptosis by suppressing reactive oxygen species. Cell 2004, 119, 529–542