Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Oncology

The cellular actin cytoskeleton is a permanent construction site. Its filaments constantly grow or shrink, form branches, or get disrupted, attach to membranes or to cargo vesicles.

- LIMK1

- kinase

1. Introduction

The balance between actin dynamics and stability is adjusted by accessory proteins such as actin-depolymerizing factors (ADFs). Binding of ADFs destabilizes the filaments and leads to severing and disassembly of the affected filament sections [1]. The ADF activity, however, is regulated by phosphorylation (Figure 1A). When phosphorylated by LIM domain kinases (LIMKs), the ADFs are inactive [2]. Dephosphorylation by Slingshot homolog 1 (SSH1) restores ADF activity [3]. Like this, the LIMKs and SSH1 control the dynamics of the actin cytoskeleton, with significant roles in physiology and disease [4]. There are two LIMKs expressed in humans, namely LIMK1 and LIMK2, both containing a kinase domain in their C terminus (Figure 1B). To add another layer of complexity, several LIMK splicing variants were identified on the mRNA and protein level [5]. This review explores structural aspects of LIMK catalytic activity and regulation and discusses how a better understanding of LIMK features enables pharmacological targeting of the actin cytoskeleton plasticity.

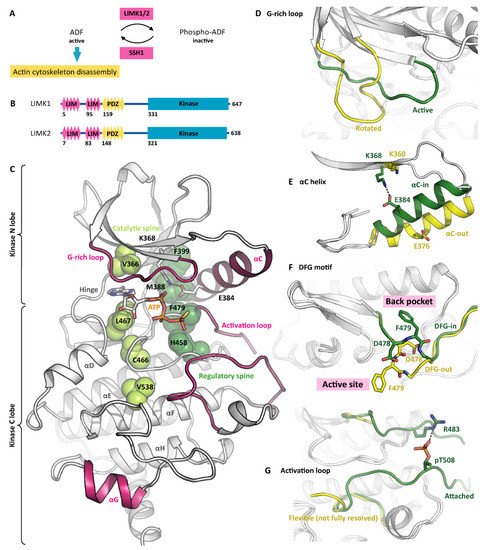

Figure 1. The LIMK conformational space. (A) LIMK1/2 and the phosphatase SSH1 control the dynamics of the actin cytoskeleton. ADF—actin depolymerizing factor. (B) Both LIMK1 and LIMK2 contain N-terminal protein interaction modules and a C-terminal kinase domain. (C) With ATP-γ-S bound, LIMK1 adopts the canonical active-kinase conformation. The catalytic and regulatory spines are fully formed (indicated in green). Please note the G-rich loop enclosing the co-substrate, the αC-in conformation, the attached activation loop, and the unusual orientation of the αG helix (all indicated in pink). PDB ID 5L6W. (D) Inhibitor binding can induce a rotated G-rich loop conformation. PDB IDs 5L6W and 5NXD. (E) The αC helix is capable of adopting both, the αC-in and the αC-out conformation. PDB IDs 5L6W and 5NXD. (F) The DFG motif in the base of the activation loop switches between the DFG-in and the DFG-out conformation. PDP IDs 5L6W and 5NXD. (G) Conformational plasticity is also observed in the activation loop, which can either be attached to the C lobe or flexible. Please note that the flexible loop is not fully resolved in the crystal structure. PDB IDs 5HVJ and 5NXC.

2. Pharmacological Targeting of LIMKs

2.1. LIMKs Are Involved in Human Disease

In line with its fundamental role in regulating actin dynamics [2], changes in LIMK signalling were frequently linked to human pathology. Recent examples include amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [6], fragile-X mental retardation syndrome [7], neurofibromatosis type 2 [8], colorectal cancer progression [9] and castration-resistant prostate cancer [10] (a critical target evaluation is not in the scope of this review). The suggested disease rationales differ in terms of cause and signalling pathway. Interestingly, however, they all involve hyperactive LIMKs, indicating that patients will potentially benefit from the inhibition of LIMK kinase activity. From the pharmacology perspective, this is good news since it is technically more feasible to develop kinase inhibitors than kinase activators. Indeed, several inhibitors have been developed to date. In the last sections of the review, general aspects of LIMK inhibitor development are discussed.

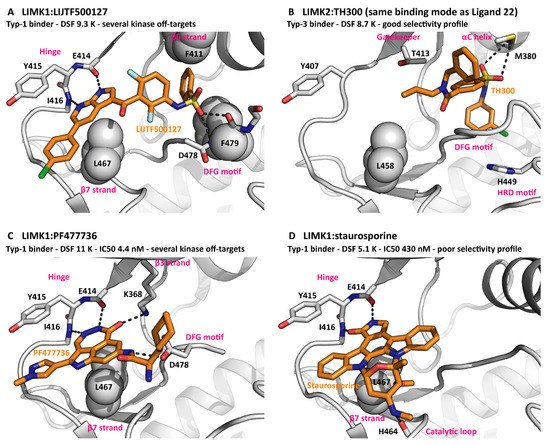

2.2. LIMK Inhibitors Binding to the Active Site

It is common practice to target kinases with small molecules that bind to the active site. To date, 71 of such molecules have been approved as drugs by the FDA, mainly for the treatment of cancer and inflammatory disorders [11]. According to their exact position in the cleft between the kinase N and C lobes, the ligands can be classified as type-1, type-2 or type-3 inhibitors (Table 1). Notably, extended naming schemes with more detailed differentiation of inhibitor binding modes have been suggested [12]. Interestingly, the LIMKs have been targeted by inhibitors of all three main binding types, reflecting the LIMK conformational plasticity discussed above [13][14][15]. In addition to the front pocket next to the hinge region and the hydrophobic back pocket, several elements from the LIMK active site can contribute to inhibitor binding, most prominently the G-rich loop backbone, the VAIK motif lysine, the gatekeeper threonine, the HRD motif histidine and the DFG motif aspartate. This is by no means unusual for a kinase. Nevertheless, good selectivity within the kinome was achieved for the LIMK inhibitors LIMKi3 [15] and Ligand 22 [13]. The binding modes of several inhibitors are compared in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Inhibitors bound to LIMKs. (A) The type-1 binder LIJTF500127 spans from the hinge to a pocket between the β5 strand and the DFG motif. PDB ID 7ATS. (B) The type-3 binder TH300 mainly exhibits hydrophobic interactions with kinase elements surrounding the back pocket. PDB ID 5NXD. (C) PF477736 occupies the front pocket only but interacts with charged residues from the β3 strand and the DFG motif. PDB ID 5NXC. (D) The pan-kinase inhibitor staurosporine binds due to its disc shape and its hinge interactions. PDB ID 3S95. The G-rich loops are omitted for clarity reasons.

Phosphorylation of the threonine residue T508 in the activation loop locks LIMK1 in the active DFG-in state [14]. This state is preferably bound by type-1 inhibitors, while type-2 and type-3 inhibitors exclusively bind to the inactive DFG-out state. As a consequence, the affinities of type-2 and type-3 inhibitors to phosphorylated LIMK1 are dramatically reduced in comparison to the non-phosphorylated protein. On top of this, type-3 inhibitor binding to non-phosphorylated LIMK1 has no effect on LIMK1 phosphorylation by upstream kinases such as PAK1 (unpublished observations). Depending on the biological setting, type-2 and type-3 inhibitors can be employed to target the non-phosphorylated LIMKs. In any case, the phosphorylation-state specificity needs to be considered when evaluating LIMK inhibitors in a cellular environment.

2.3. Inhibitors Interfering with Substrate Recognition

The rational targeting of kinase domains via binding pockets different from the active site is challenging and requires a profound understanding of the particular catalytic mechanism [11]. Examples of such inhibitors that bind the kinase domain and remodel its protein interaction network are the allosteric MEK1 inhibitors trametinib and cobimetinib [16]. In principle, the LIMKs are ideal targets for the development of allosteric inhibitors since their catalytic mechanism is understood in detail. The CFL1 anchor helix can serve as a template for the design of inhibitory peptides. As a proof-of-concept experiment, these peptides can be probed in a LIMK1 activity assay using CFL1 as a substrate. However, with potent and selective competitive inhibitors already in place, it needs to be carefully evaluated whether this is a worthwhile endeavour.

2.4. PROTACs to Induce LIMK Degradation

While active-site inhibitors solely decrease the catalytic activity of the target kinase, PROTACs lead to ubiquitination and degradation of the protein in a cellular environment. When applied to LIMKs, both strategies are expected to have different physiological impacts since the LIMKs with their modular architecture may also act as scaffolds. An assessment of several promiscuous PROTACs demonstrated that the PROTAC strategy is suitable for the LIMKs—they were even classified as ‘highly degradable targets’ [17]. Another less kinase-centred approach is to target the LIMK PDZ domain with PROTACs. However, developing selective PDZ warheads is expected to be challenging [18].

2.5. Outlook—Isoform-Specific LIMK Inhibitors

The LIMK1 and LIMK2 kinase domains share high sequence similarity (71% identical). In the active site and the substrate docking interface there are barely any differences. More variety is found in the back of the C lobe (β7 β8 loop, αE and αI helices), a functionally unexplored part of the LIMKs. Despite the conserved active site, LIMK1 and LIMK2 differ slightly in substrate specificity [19], and several ATP-competitive inhibitors were identified that bind to LIMK1, but not to LIMK2 [14], indicating that it is indeed possible to develop isoform-specific LIMK inhibitors. An alternative approach to achieve selectivity is to develop covalent inhibitors. LIMK1 contains a cysteine in the G-rich loop (sequence GKGCFG), while LIMK2 has not (sequence GKGFFG). It can be regarded as a proof-of-concept finding that a cysteine in exactly the same position was targeted successfully in the FGFRs and in SRC [20].

Due to their involvement in the same cellular pathway and their overlapping substrate specificity, differences in the physiological roles of both LIMKs are not entirely resolved. Clues come from their tissue expression profiles. While LIMK1 is mainly expressed in the human brain, LIMK2 is widely expressed in all tissues (taken from The Human Protein Atlas). Accordingly, potential adverse effects from LIMK1 inhibition include abnormal synaptic function [21][22][23], impaired platelet activation [24] and reduced osteoblast number [25]. LIMK2 inhibition, however, was reported to impair spermatogenesis [26] and platelet function [27]. This highlights the need for isoform-specific LIMK inhibitors to validate the individual LIMKs as therapeutic targets and, in the next phase, to develop therapeutics with the lowest possible risk of severe adverse effects.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cells11010142

References

- Kanellos, G.; Frame, M.C. Cellular functions of the ADF/cofilin family at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2016, 129, 3211–3218.

- Yang, N.; Higuchi, O.; Ohashi, K.; Nagata, K.; Wada, A.; Kangawa, K.; Nishida, E.; Mizuno, K. Cofilin phosphorylation by LIM-kinase 1 and its role in Rac-mediated actin reorganization. Nature 1998, 393, 809–812.

- Niwa, R.; Nagata-Ohashi, K.; Takeichi, M.; Mizuno, K.; Uemura, T. Control of actin reorganization by Slingshot, a family of phosphatases that dephosphorylate ADF/cofilin. Cell 2002, 108, 233–246.

- Ben Zablah, Y.; Zhang, H.; Gugustea, R.; Jia, Z. LIM-Kinases in Synaptic Plasticity, Memory, and Brain Diseases. Cells 2021, 10, 2079.

- Vallée, B.; Cuberos, H.; Doudeau, M.; Godin, F.; Gosset, D.; Vourc’h, P.; Andres, C.R.; Bénédetti, H. LIMK2-1, a new isoform of human LIMK2, regulates actin cytoskeleton remodeling via a different signaling pathway than that of its two homologs, LIMK2a and LIMK2b. Biochem. J. 2018, 475, 3745–3761.

- Sivadasan, R.; Hornburg, D.; Drepper, C.; Frank, N.; Jablonka, S.; Hansel, A.; Lojewski, X.; Sterneckert, J.; Hermann, A.; Shaw, P.J.; et al. C9ORF72 interaction with cofilin modulates actin dynamics in motor neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 1610–1618.

- Kashima, R.; Roy, S.; Ascano, M.; Martinez-Cerdeno, V.; Ariza-Torres, J.; Kim, S.; Louie, J.; Lu, Y.; Leyton, P.; Bloch, K.D.; et al. Augmented noncanonical BMP type II receptor signaling mediates the synaptic abnormality of fragile X syndrome. Sci. Signal. 2016, 9, ra58.

- Petrilli, A.; Copik, A.; Posadas, M.; Chang, L.-S.; Welling, D.B.; Giovannini, M.; Fernández-Valle, C. LIM domain kinases as potential therapeutic targets for neurofibromatosis type 2. Oncogene 2014, 33, 3571–3582.

- Sousa-Squiavinato, A.C.M.; Vasconcelos, R.I.; Gehren, A.S.; Fernandes, P.V.; de Oliveira, I.M.; Boroni, M.; Morgado-Díaz, J.A. Cofilin-1, LIMK1 and SSH1 are differentially expressed in locally advanced colorectal cancer and according to consensus molecular subtypes. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 69.

- Nikhil, K.; Chang, L.; Viccaro, K.; Jacobsen, M.; McGuire, C.; Satapathy, S.R.; Tandiary, M.; Broman, M.M.; Cresswell, G.; He, Y.J.; et al. Identification of LIMK2 as a therapeutic target in castration resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Lett. 2019, 448, 182–196.

- Attwood, M.M.; Fabbro, D.; Sokolov, A.V.; Knapp, S.; Schiöth, H.B. Trends in kinase drug discovery: Targets, indications and inhibitor design. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 839–861.

- Kanev, G.K.; de Graaf, C.; Westerman, B.A.; de Esch, I.J.P.; Kooistra, A.J. KLIFS: An overhaul after the first 5 years of supporting kinase research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D562–D569.

- Goodwin, N.C.; Cianchetta, G.; Burgoon, H.A.; Healy, J.; Mabon, R.; Strobel, E.D.; Allen, J.; Wang, S.; Hamman, B.D.; Rawlins, D.B. Discovery of a Type III Inhibitor of LIM Kinase 2 That Binds in a DFG-Out Conformation. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 53–57.

- Salah, E.; Chatterjee, D.; Beltrami, A.; Tumber, A.; Preuss, F.; Canning, P.; Chaikuad, A.; Knaus, P.; Knapp, S.; Bullock, A.N.; et al. Lessons from LIMK1 enzymology and their impact on inhibitor design. Biochem. J. 2019, 476, 3197–3209.

- Ross-Macdonald, P.; de Silva, H.; Guo, Q.; Xiao, H.; Hung, C.-Y.; Penhallow, B.; Markwalder, J.; He, L.; Attar, R.M.; Lin, T.; et al. Identification of a nonkinase target mediating cytotoxicity of novel kinase inhibitors. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008, 7, 3490–3498.

- Khan, Z.M.; Real, A.M.; Marsiglia, W.M.; Chow, A.; Duffy, M.E.; Yerabolu, J.R.; Scopton, A.P.; Dar, A.C. Structural basis for the action of the drug trametinib at KSR-bound MEK. Nature 2020, 588, 509–514.

- Donovan, K.A.; Ferguson, F.M.; Bushman, J.W.; Eleuteri, N.A.; Bhunia, D.; Ryu, S.; Tan, L.; Shi, K.; Yue, H.; Liu, X.; et al. Mapping the Degradable Kinome Provides a Resource for Expedited Degrader Development. Cell 2020, 183, 1714–1731.e10.

- Christensen, N.R.; Čalyševa, J.; Fernandes, E.F.A.; Lüchow, S.; Clemmensen, L.S.; Haugaard-Kedström, L.M.; Strømgaard, K. PDZ Domains as Drug Targets. Adv. Ther. 2019, 2, 1800143.

- Amano, T.; Tanabe, K.; Eto, T.; Narumiya, S.; Mizuno, K. LIM-kinase 2 induces formation of stress fibres, focal adhesions and membrane blebs, dependent on its activation by Rho-associated kinase-catalysed phosphorylation at threonine-505. Biochem. J. 2001, 354, 149–159.

- Chaikuad, A.; Koch, P.; Laufer, S.A.; Knapp, S. The Cysteinome of Protein Kinases as a Target in Drug Development. Angewandte Chemie (Int. Ed. Engl.) 2018, 57, 4372–4385.

- Meng, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Meng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, G.; Asrar, S.; Nakamura, T.; Jia, Z. Regulation of ADF/cofilin phosphorylation and synaptic function by LIM-kinase. Neuropharmacology 2004, 47, 746–754.

- Todorovski, Z.; Asrar, S.; Liu, J.; Saw, N.M.N.; Joshi, K.; Cortez, M.A.; Snead, O.C.; Xie, W.; Jia, Z. LIMK1 regulates long-term memory and synaptic plasticity via the transcriptional factor CREB. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2015, 35, 1316–1328.

- Meng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tregoubov, V.; Janus, C.; Cruz, L.; Jackson, M.; Lu, W.Y.; MacDonald, J.F.; Wang, J.Y.; Falls, D.L.; et al. Abnormal spine morphology and enhanced LTP in LIMK-1 knockout mice. Neuron 2002, 35, 121–133.

- Estevez, B.; Stojanovic-Terpo, A.; Delaney, M.K.; O’Brien, K.A.; Berndt, M.C.; Ruan, C.; Du, X. LIM kinase-1 selectively promotes glycoprotein Ib-IX-mediated TXA2 synthesis, platelet activation, and thrombosis. Blood 2013, 121, 4586–4594.

- Kawano, T.; Zhu, M.; Troiano, N.; Horowitz, M.; Bian, J.; Gundberg, C.; Kolodziejczak, K.; Insogna, K. LIM kinase 1 deficient mice have reduced bone mass. Bone 2013, 52, 70–82.

- Takahashi, H.; Koshimizu, U.; Miyazaki, J.; Nakamura, T. Impaired spermatogenic ability of testicular germ cells in mice deficient in the LIM-kinase 2 gene. Dev. Biol. 2002, 241, 259–272.

- Antonipillai, J.; Mittelstaedt, K.; Rigby, S.; Bassler, N.; Bernard, O. LIM kinase 2 (LIMK2) may play an essential role in platelet function. Exp. Cell Res. 2020, 388, 111822.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!