Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is an acute, severe lung injury that is characterized by inflammatory cascades, hypoxemia, and diffuse lung involvement. In 1967, ARDS was first described as an acute hypoxic lung injury with infectious and traumatic triggers, similar to neonatal congestive atelectasis and hyaline membrane disease. Since then, several definitions of ARDS have been established, but the Berlin definition is the latest and most widely accepted. The diagnostic criteria are summarized as an acute injurious lung event with diffuse bilateral lung opacities of non-cardiogenic origin on imaging.

1. Introduction

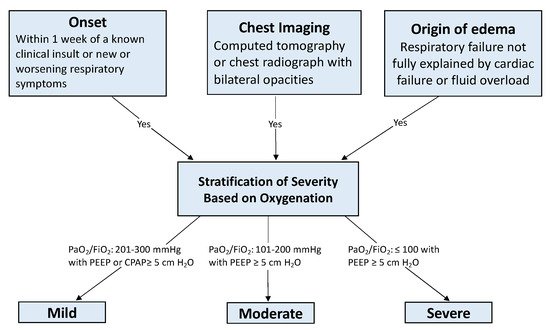

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is an acute, severe lung injury that is characterized by inflammatory cascades, hypoxemia, and diffuse lung involvement. In 1967, ARDS was first described as an acute hypoxic lung injury with infectious and traumatic triggers, similar to neonatal congestive atelectasis and hyaline membrane disease [

1]. Since then, several definitions of ARDS have been established, but the Berlin definition is the latest and most widely accepted [

2]. The diagnostic criteria are summarized as an acute injurious lung event with diffuse bilateral lung opacities of non-cardiogenic origin on imaging (See

Figure 1).

Figure 1. Berlin Diagnostic Criteria [

2]. Abbreviations: PaO

2 = arterial partial pressure of oxygen; FiO

2 = fraction of inspired oxygen; PEEP = positive end expiratory pressure; CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure.

ARDS, in regards to incidence, morbidity, and mortality, is a sinister clinical conundrum—a condition that is both common and devastating. The age-adjusted incidence of ARDS in individuals with PaO

2/FiO

2 (arterial partial pressure of oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen) ratio ≤ 300 mmHg is 86 per 100,000 person-years and 64 per 100,000 person-years for individuals with PaO

2/FiO

2 ratio ≤ 200 mmHg [

3]. This approximates to 10% of intensive care unit (ICU) patients and 23% of patients on mechanical ventilation [

4]. Patients between the ages of 15 and 19 have a 24% mortality, whereas older patients suffer to a greater degree with mortality rates approaching 60% [

3].

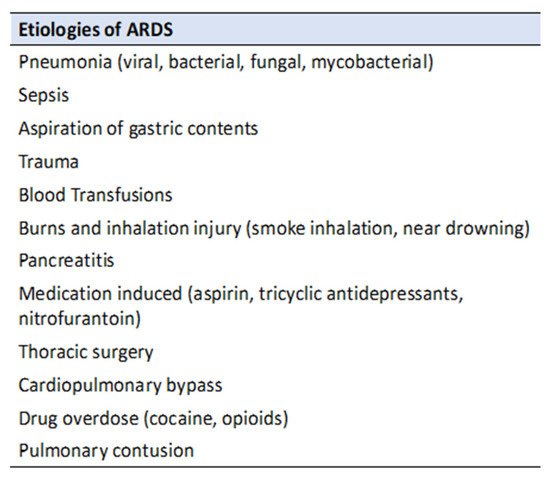

There are many well established and potential etiologies of ARDS (see

Figure 2), but around 85–90% are caused by pneumonia, sepsis, aspiration of gastric contents, trauma, or blood transfusion [

5,

6,

7]. The hallmark pathophysiological mechanisms of ARDS follow a predictable pattern that begins with an initial insult with a subsequent inflammatory response, which leads to endothelial damage and increased pulmonary capillary permeability. The subsequent proliferation and fibrosis stages attempt to repair the initial inflammatory insult and endothelial damage. More specifically, the fibrotic phase recruits fibroblasts and implements repair mechanisms that cause intra-alveolar fibrosis and capillary obliteration [

6,

7]. This intra-alveolar architectural change leads to prolonged mechanical ventilation and increased mortality [

6].

Figure 2. Common etiologies of ARDS.

2. Lung Protective Ventilation

Lung protective ventilation is the mainstay of ventilatory management of patients with ARDS and plays a critical role in improving clinical outcomes. Lung protective ventilation strives to prevent over-distention, or “stretch”, of the aerated lung, as this has been shown to disrupt both the pulmonary endothelium and epithelium, resulting in lung inflammation, atelectasis, hypoxemia, and the release of inflammatory mediators [

8]. It is recommended that patients be ventilated with low tidal volumes (4–8 mL/kg of predicted body weight) [

8]. Many of these parameters were derived from the ARMA trial conducted by ARDSNet investigators [

8]. This landmark study demonstrated significantly reduced hospital mortality and duration of mechanical ventilation when a lung protective ventilatory strategy was utilized [

8]. Prior to this study, traditional ventilation strategies focused on increasing arterial oxygen saturation with the use of higher tidal volumes at the expense of alveolar distension. This contributed to stretch induced disruption of the alveolar endothelium and a potentiation of the innate inflammatory response—further exacerbating the underlying mechanism of ARDS. The ARMA protocol derived from the ARDSNet trial provided evidence that reducing alveolar stretch injury with low tidal volumes (6 mL/kg of predicted body weight) improves survival and was subsequently adopted as the mainstay of ARDS ventilatory management [

8].

Lung protective ventilation includes the use of high PEEP but this has a less defined benefit in ARDS management. In the ARMA trial, PEEP was set according to the amount of FiO

2 a patient needed, using a titration table. Studies such as the ALVEOLI trial reveal that utilization of an even higher PEEP titration table does not result in improvement in patient outcomes [

9]. Thus, though the utilization of high PEEP is a part of lung protective ventilation, “how high” is not clearly defined.

In addition, lung protective ventilation includes targeting low plateau pressures [

10]. Plateau pressures can be referred to as a measure of pulmonary compliance. It is generally accepted that plateau pressures are tolerable up to 30–32 cm H

2O. The ARMA trial also found that coupled with low tidal volume, a lower plateau pressure helps to reduce mortality in patients with ARDS [

8]. Plateau pressures in turn can help risk stratify cut-off values during mechanical ventilation for potential barotrauma and lung parenchyma injury. A better understanding of mechanical ventilatory support and its related ventilator induced lung injury (VILI) is an essential component of managing patients with ARDS. Failure to comply with lung protective ventilation strategies might enhance the risk of VILI which involves excessive stress to the lungs (high transpulmonary pressure), and increased strain (alveolar-overdistention) which eventually leads to barotrauma, alveolar rupture, and development of pulmonary edema [

11,

12].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jcm11020319