Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Agronomy

In Europe, there is an increasing interest in pulses both for their beneficial effects in cropping systems and for human health. However, despite these advantages, the acreage dedicated to pulses has been declining and their diversity has reduced, particularly in European temperate regions, due to several social and economic factors. This decline has stimulated a political debate in the EU on the development of plant proteins. By contrast, in Southern countries, a large panel of minor pulses is still cropped in regional patterns of production and consumption.

- grain legumes

- crop diversification

- proteins

1. Introduction

There is an increasing debate about the importance of plant-based proteins and the diversification of protein sources for food or feed [1]. Plant-based proteins originate in several botanical families but are mainly concentrated in legumes. Despite the importance of grain legume, their production and consumption are declining worldwide [2][3], whereas the acreage dedicated to soybean is continuously increasing due to the intensification of livestock production [3]. Although grain legume diversity is very high from a worldwide perspective [4], these species often have local patterns of production and consumption in several developed and developing countries [5]. Worldwide grain legumes production increased by 15% between 2016 and 2017. This increase in production occurred in each continent, except America where production remained stable. Soybean production also increased during this period. This increase was mainly due to the largest producers, North and South America. Based on the most recent available FAOSTAT data [6], there are four main pulses cultivated worldwide. Beans (all Phaseolus species included) were the most produced in 2019 (Table 1), half of which were produced in Asia. Peas are produced in Europe and in North America; however, 83% of chickpeas production (including the species Cicer arietinum) was harvested in Asia. Beyond these four common grain legumes, cowpea production reached 8.9 million tons, but was concentrated in Africa (97%) and pigeon pea production, which attained 4.4 million tons, was concentrated in Africa (15%) and Asia (83%). Broad beans (including Vicia faba, horse bean, broad bean and field bean) were also largely cultivated in 2019 with more than 5.4 million tons harvested. Lupins were produced mainly in Oceania (47%) and Europe (37%). Vetches with a production of 0.9 million tons were produced in Europe (31%) and Africa (43%) and Bambara bean was only cultivated in Africa, with an annual production of 0.2 million tons. The other pulses, grouped together for statistical purposes, accounted for 4.5 million tons worldwide. The only six pulses that are exchanged internationally are, in decreasing order of importation quantity, peas, with 37.6% of all world imports, representing 6.5 million, beans with 21%, lentils with 17%, chickpeas with 11%, broad beans with 5% and Bambara beans with only 0.01% according to the FAO data on 2016 market exchanges.

Table 1. World production of pulses in tons (T) and contribution percentage (%) of each continent (Faostat 2019).

| World (T) | Africa (%) | America (%) | Asia (%) | Europe (%) | Oceania (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bambara beans | 228,920 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Beans, dry | 28,902,672 | 24.4 | 24.4 | 49.7 | 1.3 | 0.3 |

| Broad beans, horse beans, dry | 5,431,503 | 27.0 | 4.0 | 33.6 | 29.4 | 6.0 |

| Chick peas | 14,246,295 | 4.9 | 6.1 | 83.4 | 3.6 | 2.0 |

| Cow peas, dry | 8,903,329 | 96.8 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Lentils | 5,734,201 | 3.3 | 42.7 | 42.5 | 2.2 | 9.3 |

| Lupins | 1,006,842 | 7.5 | 6.3 | 0.0 | 39.0 | 47.1 |

| Peas, dry | 14,184,249 | 3.9 | 39.3 | 18.1 | 37.0 | 1.7 |

| Pigeon peas | 4,425,969 | 15.1 | 1.8 | 83.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Pulses, others | 4,553,029 | 31.5 | 0.9 | 45.3 | 22.0 | 0.3 |

| Vetches | 762,795 | 42.6 | 12.7 | 12.4 | 31.4 | 0.9 |

| Pulses, total | 88,379,804 | 24.1 | 18.7 | 44.3 | 10.8 | 2.2 |

Minor pulses are produced and consumed locally worldwide, and there is no exchange between countries unless they are already cultivating and consuming these minor pulses [7]. This is more a consequence of food habits than because of pedoclimatic or agronomic constraints.

In 2018 in Europe, only 1.3% of the cultivated acreage was dedicated to pulses (Eurostat) where peas covered 37% of the surface followed by broad beans, field beans (26%) and sweet lupins (6%). The rest (26.4%) came from other dry pulses such as lentils, chickpeas and beans (Eurostat).

However, the production of pulses has decreased during the last five decades [8]. Several factors have driven this decrease. First, the reduction of human consumption of vegetal proteins was negatively correlated to the increase in the standard of living of the population and the substitution by animal proteins [9]. Besides, less time is devoted to cooking, which is essential to reduce the impact of antinutritional factors of pulses, leading to reduced consumption [10]. Second, the increasing import of cheap soybean meal to feed livestock from North and South America (2017) has induced a reduction in the price of meat. The availability of inexpensive proteins has supported the intensification of livestock production, which, at the same time, has dissociated livestock breeding from crop production for feeding [11]. The separation of protein and livestock production led to an intensification and a reduction of the number of cultivated crops, chosen for their economical performances. Moreover, as Watson et al. [8] argued, the yield increase of cereals in Europe since the 1970s was not followed by a similar yield increase of protein crops, leading to an expansion of cereal acreage while protein crops remained less attractive for farmers. However, since 2015, this trend has ended in Europe, probably because of both the increase in organic farming and the different policy instruments supporting protein crops [12].

European farmers, particularly those in arable systems, look to diversify the crop rotations to more sustainable and resilient cropping systems [13]. One of the major groups of crops targeted for diversification is grain legumes [13][14]. Several scholars have been interested in grain legumes because of their potential uses for food, feed and bioenergy/biomaterials but also because of the agroecosystem services they provide [2][3]. However, there is a general lack of knowledge and references regarding these grain legumes in terms of production potential in Northern countries and also about the diversity of their possible usage. Moreover, some scholars argue that the low adoption by European farmers of grain legumes compared with other crops is caused by low productivity and low profit margins, technological lock-in, and low temporal yield stability [15][16][17]. Reckling et al. [18] have underlined that in Northern Europe, the grain legume yield is as stable as that of other major spring crops, e.g., spring cereals or rape seed. Yield stability is also enhanced in the other crops of the cropping system by grain legumes, as demonstrated by Petrova Chimonyo et al. [19] in maize-based cropping systems. Mawois et al. [20] have studied the trajectories of farms that increased the proportion of grain legumes in their crop rotations, highlighting three levels for their successful introduction: the stability of the supply (both as on-farm consumption and in the food supply chain), the benefits of grain legumes as the preceding crop and/or the involvement of farmers in peer groups.

2. Innovative Pulses for Western European Temperate Regions

2.1. Types of Pulses and Agronomical Needs

Pulses are found worldwide, and some of them are adapted to temperate climates (kidney bean, lupins) (Table 3) whilst a larger number can be found in tropical or subtropical areas (adzuki bean, cowpea) and a few can be found in both areas (soybean, broad beans). Crops such as the common bean that can grow under both temperate and tropical climate conditions are grown during the spring–summer period and in cold (winter) periods in temperate areas, or at high altitudes in tropical areas [21][22][23]. In soybean, on the other hand, several maturity groups adapted to different pedoclimatic conditions have been developed [24][25]. Most of them have a crop length between 2 and 6 months, but it is highly variable even within a species. However, those crop lengths have been observed in tropical conditions allowing a high GDD, and the exact GDD is not precisely defined in the literature. Some crops have longer cycles that can reach nearly a year (i.e., cowpea and sword bean [26]), and others can be cultivated as an annual plant (i.e., urad, tepary bean [27]) or as a perennial (i.e., pigeon pea [28], morama bean, Mucuna atropurpurea [26] and yam bean [29]). The perennial pulses could also be cultivated as annuals depending on the agronomical practices of the country. Despite the in-depth research conducted it was difficult to identify the intra species genetic diversity available that may be conducive to a larger potential for one species to spread to other climatic conditions or agronomical practices.

Table 3. Pulses’ agronomic requirements and potential yields.

| Pulses—Common Name | Temperature (°C) Min; Max; Optimal |

Crop Length | Water Requirements (mm) |

Yield (t/Ha) | Kg N Fixed (kg/ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adzuki bean | 5–10; 34; 15–30 | 60–190 d | 500–1700 | 0.5–3.5 | 100 |

| Butterfly pea | 5; 35; 20–28 | 120–194 d | 400–1750 | 0.7 | - |

| Cowpea | 15; 35; 25–35 | 60–340 d | 500–1500 | 0.2–7 | 12–50 |

| Fenugreek | −4; -; 18–27 | 90–100 d | 300–400 | - | - |

| Grass pea | 20; -; 10–25 | 90–180 d | 400–650 | 0.3–10.5 | 25–50 |

| Horse gram | -; 40; 20–32 | 120–150 d | 380–900 | 0.5 | - |

| Itching bean | -; -; 19–27 | - | 400–3000 | 0.2–2 | - |

| Kidney bean | −1; 30;15–20 | 65–105 d | 300–600 | 2.2 | 20–44 |

| Lablab | -; -; 18–30 | 54–220 d | 650–3000 | 1.4–4.5 | 20–140 |

| Lima bean | >0; >37; 16–27 | 115–180 d | 900–1500 | 0.4–5 | 40–60 |

| Moth bean | 25; 45; 24–32 | 70–90 d | 200–750 | 0.07–2.6 | - |

| Navy bean | 12; 35; 22–30 | 53–300 d | 400 | 0.5–5 | 125 |

| Pigeon pea | 0; 40; 18–29 | 3–5 y | 600–1400 | 0.6–5 | 69–134 |

| Pinto bean | -; 36; 21–25 | 90–100 d | - | 0.5–3.9 | - |

| Rice bean | 10; 40; 25–35 | 120–150 d | 700–1700 | 0.2–2.7 | - |

| Sword bean | -; -; 25–30 | 150–300 d | 900–1500 | 1.5–5.4 | 75–230 |

| Tarwi | <0; -; - | 150–330 d | - | 0.6–4.8 | 100 |

| Tepary bean | 8; >32; 17–25 | 60–120 d | 400–1700 | 0.4–1.7 | - |

| Urad | -; -; 25–35 no frost | 60–140 d | 600–1000 | 0.3–2.5 | 18 |

| Velvet bean | 5; -; 19–27 | - | 1200–1500 | 0.5–3.4 | 60–330 |

| Winged bean | -; -; 20–30 | 120–180 d | 1000 | 0.7–1.9 | - |

| Broad bean | −12; 30; 18–27 | 90–220 d | 700–1200 | 1.1–2.2 | 33–550 |

| Chickpea | −11; >32; 10–29 | 90–180 d | 500–1800 | 1–5.5 | 35–140 |

| Common bean | −9; 38; - | 70–110 d | 274–550 | 0.9–2.6 | 465 |

| Field pea | <0; -; 7–30 | 90–180 d | 400–1000 | 1–4 | 30–96 |

| Lentil | 2; 35; 6–27 | 80–130 d | 300–2400 | 0.8–7 | 50 |

| Lupin | <0; -; 18–24 | 115–330 d | 400–1000 | 0.5–5 | 90–400 |

d means days (annual crops) and y years (pluriannual crops), °C degrees Celsius. In grey, a comparison with the same search was repeated for major pulses.

In temperate climates, pulses are mainly cultivated as main crops or in association with cereals [30], whereas in tropical countries, we can find associations with corn [31], coffee [32], cassava [33] and other diverse crops [34][35]. In the latter crop, little or no fertilization or pest management is required. Two pulses are cultivated not for their grains but for their tuber production, making the grains a coproduct (yam bean and African yam bean [36][37]). Among the studied species, minimal temperature has been retrieved in 25 species over 57. Among them, a few minor pulses resist cold temperatures (Tarwi bean, pigeon pea, kidney bean and fenugreek). Among the major pulses, five over six tolerate negative temperatures. The other pulses require positive temperatures during their entire life cycle, and in most cases, above 10 °C. The optimal growing temperature is characterized in the literature only in 33 out of 47 species, but the temperature intervals are often wide. The maximal temperature is retrieved in 23 species over 47 but it will not be a constraint in temperate climates of Western Europe.

Legume plants can fix atmospheric nitrogen (up to 550 kgN/ha in exceptional examples [26]. Table 3 and Appendix A describe crop requirements and potential yield. Most pulses are grown without adding nitrogen to the crop, even though a small quantity at sowing time can aid in proper development of the plant before the symbiotic relationship with nitrogen-fixing bacteria becomes efficient. It is also recommended that poor soil be fertilized with phosphorus and potassium.

The requirements of common pulses are equivalent to those of minor pulses; the main difference is their adaptation to a temperate climate, as they are adapted to low temperatures during a part of their growth cycle. The water needs and fertilization requirements of both are similar. The data collected on the fixed nitrogen cannot be used to make a comparison between species because they were obtained in most of the cases in one single pedoclimatic condition or the methodology to assess it was not identical, which may lead to big differences not related to the real capacity of a species to take up nitrogen [38][39][40].

2.2. Nutritional Characteristics

Pulses have an interesting nutritional profile (Table 4), because they have high protein content with a mean value in our sample of 23% (rice bean has the lowest content with 19.7% [40] and tarwi [41] has the highest content, 51%), low fat content with a mean value of 3.8% and a small percentage of saturated fatty acids. Pulses also provide fiber, vitamins and minerals which are important for human health.

Table 4. Nutritional profile of pulses.

| Pulses—Common Name | Energy (kcal/100 g) | Protein (%) | Oil (Saturated FA) (%) | Carbohydrate (%) | Fiber (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adzuki bean | 329 | 19.9 | 0.5 (0.2) | 62.9 | 12.7 |

| Butterfly pea | - | 25.2 | 3.7 | 19.9 | 9.2 |

| Cowpea | 343 | 23.9 | 2.1 (0.5) | 59.6 | 10.7 |

| Fenugreek | 323 | 23.0 | 6.4 | 58.0 | 25.0 |

| Grass pea | - | 24.4 | 2.8 (0.8) | 55.94 | 11.4 |

| Horse gram | 280 | 22 | 0.6 | 37.5 | 5.7 |

| Itching bean | 382 | 27–37 | 6.6–8.8 | 46–53 | 6–10 |

| Kidney bean | 333 | 23.6 | 0.8 (0.1) | 30.0 | 24.0 |

| Lablab | 344 | 21–29 | 1.7 (0.3) | 60.74 | 25.6 |

| Lima bean | 338 | 21.5 | 0.7 (0.2) | 63.4 | 19.0 |

| Moth bean | 343 | 23–26 | 1.6 (0.4) | 61.5 | 5 |

| Navy bean | 337 | 22.3 | 1.5 (0.2) | 60.8 | 15.3 |

| Pigeon pea | 343 | 13–26 | 1.5 (0.3) | 62.8 | 15 |

| Pinto bean | 347 | 21.4 | 1.2 (0.2) | 62.6 | 15.5 |

| Rice bean | 338 | 18–19 | 0.5 (0.3) | 59.1 | 7.1 |

| Sword bean | 361 | 24–30 | 2.6–9.8 (-) | 41–59 | 7–13 |

| Tarwi | 440 | 41–51 | 14–24 (19) | 28.2 | 7.1 |

| Tepary bean | 353 | 19–24 | 1.2 (-) | 67.8 | 4.8 |

| Urad | 341 | 25.2 | 1.6 (0.1) | 59.0 | 18.3 |

| Velvet bean | 373 | 20–29 | 6–7 | 50–61 | 9–11 |

| Winged bean | 428 | 30–35 | 16.3 (2.3) | 41.7 | 11–26 |

| Broad bean | 341 | 26.1 | 1.53 (0.3) | 58.3 | 25 |

| Chickpea | 378 | 11–31 | 6.0 (0.6) | 63.0 | 12.2 |

| Common bean | 20–24 | 0.8 (0.6) | 75.5 | - | |

| Field pea | 352 | 23.8 | 1.2 (0.2) | 63.7 | 25 |

| Lentil | 352 | 24.6 | 1.1 (0.2) | 63.4 | 10.7 |

| Lupin | 371 | 36.2 | 9.7 (1.2) | 40.37 | 18.9 |

In grey, a comparison with the same search was repeated for major pulses.

2.3. Antinutritional Characteristics

All pulses contain one or more antinutritional compounds (Appendix D) and although the concentration is under the lethal dose, a regular or almost exclusive consumption may induce certain medical problems, such as the lathyrism caused by grass pea in European populations after the wars [42] that led to a law forbidding the consumption of grass pea grain or its derivatives in Spain [43]. Efforts have been made to breed new varieties with reduced content of the neurotoxin [44].

Appendix D reports data from research articles that analyzed one or several compounds. The other columns indicate the presence of other toxic molecules that are only present in some crops, even in a single crop, such as β-ODAP (beta-oxalyl-diamino-propionic acid) in grass pea or gossypol in cotton. Itching and velvet bean present the highest content of phytic acid, with some varieties reaching between 53 and 57 mg/g [45], whereas the other pulses varied from 0.5 to 41 mg/g. In the case of tannins, some varieties of African yam bean contained up to 18.1 mg/g [46], while other pulses contained from 0.01 [47] to 96 [48] mg/g. Saponins reached the highest values in some varieties of navy bean, but have lower values than some varieties of lentils or chickpea [49]. Trypsin inhibitors were found in high quantities in sesban seeds, reaching 140 mg/100 g [50]. Finally, lectins were less abundant in a few species of pulses; mung bean seeds contained the highest quantity, with 15.8 mg per 100 g [51].

2.4. Potential for Minor Pulse Cultivation in European Temperate Regions

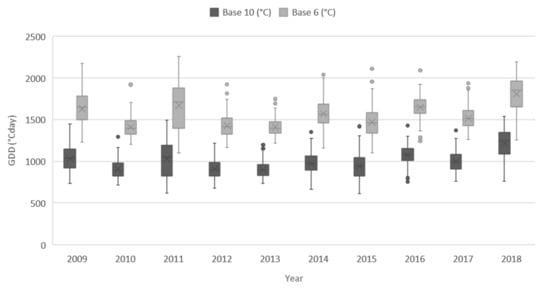

Analyses of the meteorological data showed that in the considered European temperate regions between 1998 and 2018, the total number of observed situations was 7456. The minimal duration of good cropping conditions was 121 days, and the average maximum was 140 days. The most frequent duration was 120–125 days (18.5%) followed by 125–130 (15.3%) and 130–135 days (10.5%). The daily temperature varied from 14.9 to 20.0 °C, with a mean of 17.1 °C. Sowing was possible in 12.6% of the situations in March, 54.1% in April, 34.0% in May and only 1.8% in June, whereas the possible harvest day was concentrated between September (64.7%) and October (33.6%). The GDD in base 6 °C varied from 1102 to 2430 °C day, the most frequent being 1500 to 1600 °C day (19%), 1600–1700 °C day (18.3%), 1400–1500 (16.2%) and 1700–1800 (13.2%). The GDD in base 10 °C varied from 615 to 1654 °C day with a mean of 994 °C day being the most frequent, 1000–1100 (25.5%), followed by 1100–1200 (20.6%) and 900–1000 (20.2%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Bow whispers of the growing degrees days (GDD, °C day) cumulative distributions in several locations in European temperate regions (see Section 2.4) within the last 10 studied years for a base temperature of 6 and 10 °C (source: own calculation from the Agri4cast database).

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/agronomy12010170

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!