Neuromodulators at the periphery, such as neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES), have been developed as add-on tools to regain upper extremity (UE) paresis after stroke, but this recovery has often been limited. To overcome these limits, novel strategies to enhance neural reorganization and functional recovery are needed. This review aims to discuss possible strategies for enhancing the benefits of NMES. To date, NMES studies have involved some therapeutic concerns that have been addressed under various conditions, such as the time of post-stroke and stroke severity and/or with heterogeneous stimulation parameters, such as target muscles, doses or durations of treatment and outcome measures.

- cortical reorganization

- functional near-infrared spectroscopy

- upper extremity paresis

- neuromuscular electrical stimulation

- neuronal plasticity

- neurorehabilitation

- repetitive peripheral neuromuscular magnetic stimulation

1. Introduction

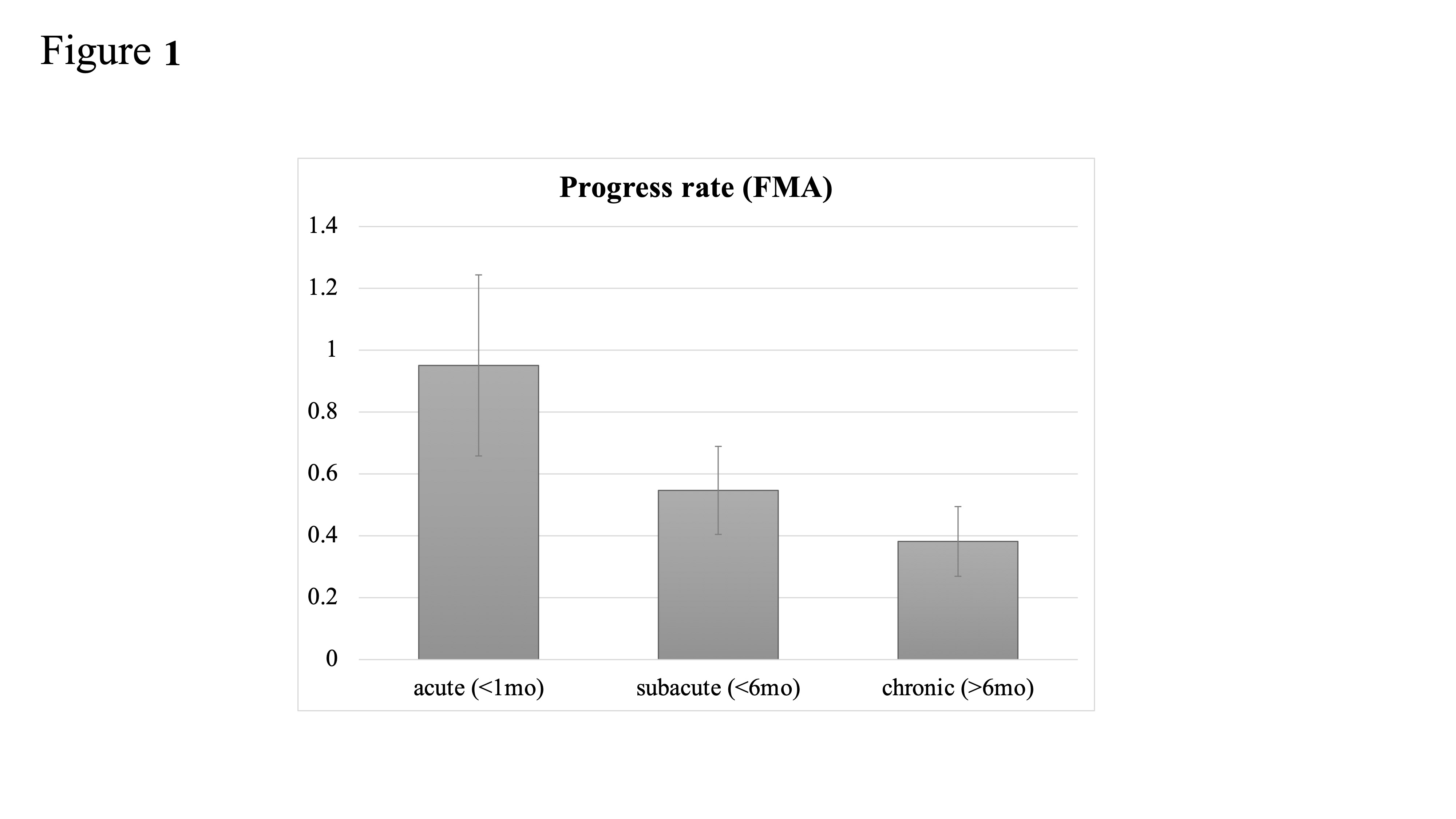

2. Time to NMES following Stroke: Is Earlier Intervention More Effective?

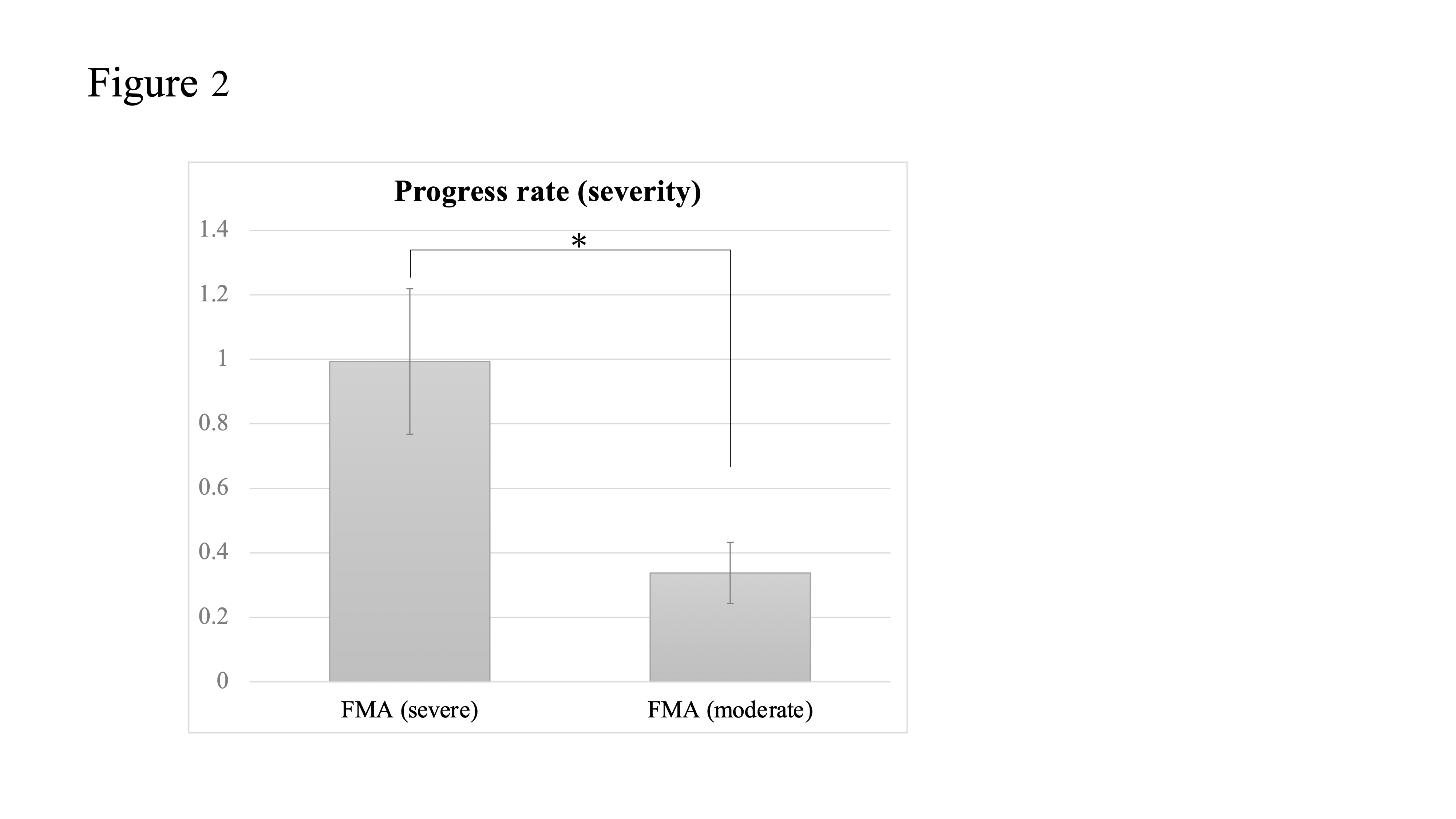

3. Stroke Severity

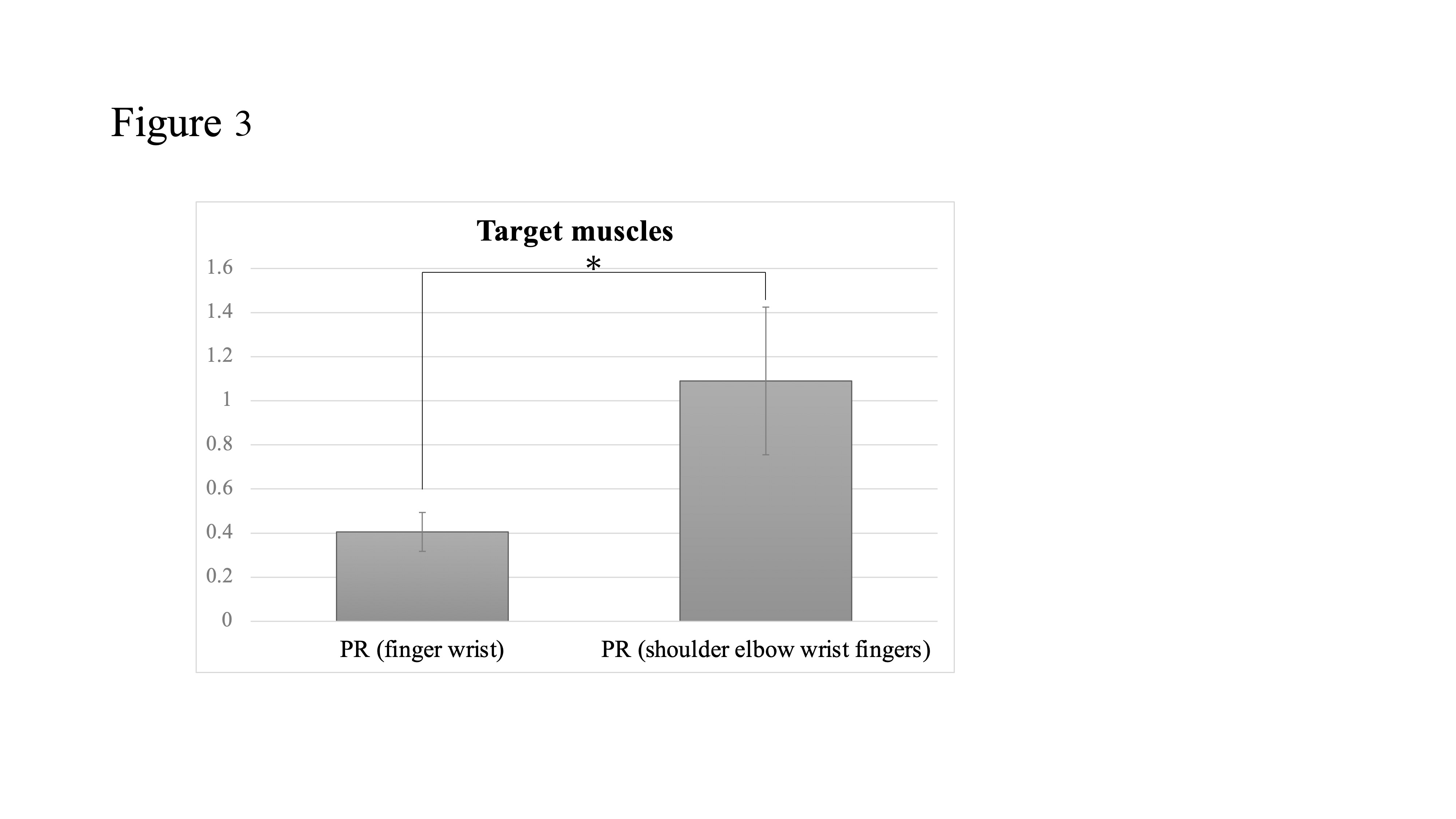

4. Target Muscles

5. Is a Higher Dose of NMES More Beneficial?

6. Which of the NMES Modes Is More Effective?

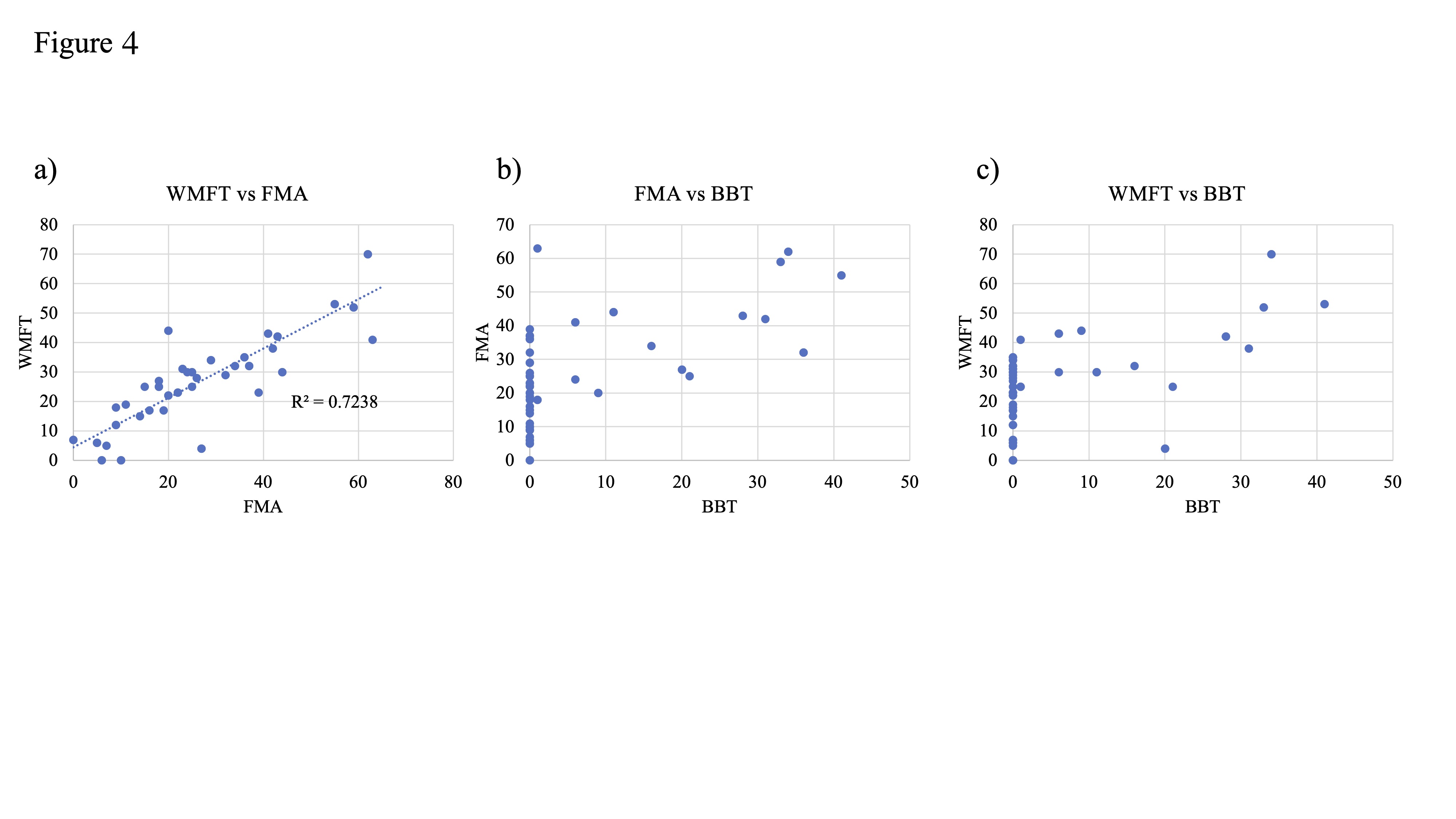

7. Sensitivity of Measure Outcomes to Motor Function

8. Possibility of rPMS for Recovery from UE Paresis

9. Effects of Neuromodulators: Long-Term and Long-Lasting?

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/app12020810

References

- Hsu, W.Y.; Cheng, C.H.; Liao, K.K.; Lee, I.H.; Lin, Y.Y. Effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on motor functions in patients with stroke: A meta-analysis. Stroke 2012, 43, 1849–1857.

- Le, Q.; Qu, Y.; Tao, Y.; Zhu, S. Effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on hand function recovery and excitability of the motor cortex after stroke: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 93, 422–430.

- Hummel, F.; Celnik, P.; Giraux, P.; Floel, A.; Wu, W.H.; Gerloff, C.; Cohen, L.G. Effects of non-invasive cortical stimulation on skilled motor function in chronic stroke. Brain 2005, 128, 490–499.

- Schlaug, G.; Renga, V.; Nair, D. Transcranial direct current stimulation in stroke recovery. Arch. Neurol. 2008, 65, 1571–1576.

- Daly, J.J.; Hogan, N.; Perepezko, E.M.; Krebs, H.I.; Rogers, J.M.; Goyal, K.S.; Dohring, M.E.; Fredrickson, E.; Nethery, J.; Ruff, R.L. Response to upper-limb robotics and functional neuromuscular stimulation following stroke. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2005, 42, 723–736.

- Popovic, D.B.; Popovic, M.B.; Sinkjaer, T. Neurorehabilitation of upper extremities in humans with sensory-motor impairment. Neuromodulation 2002, 5, 54–66.

- Eraifej, J.; Clark, W.; France, B.; Desando, S.; Moore, D. Effectiveness of upper limb functional electrical stimulation after stroke for the improvement of activities of daily living and motor function: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 40.

- Wattchow, K.A.; McDonnell, M.N.; Hillier, S.L. Rehabilitation Interventions for Upper Limb Function in the First Four Weeks Following Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Evidence. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 367–382.

- Howlett, O.A.; Lannin, N.A.; Ada, L.; McKinstry, C. Functional electrical stimulation improves activity after stroke: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 96, 934–943.

- Whitall, J. Stroke rehabilitation research: Time to answer more specific questions? NeuroRehabilit. Neural Repair 2004, 18, 3–8.

- Obayashi, S.; Takahashi, R. Repetitive peripheral magnetic stimulation improves severe upper limb paresis in early acute phase stroke survivors. NeuroRehabilitation 2020, 46, 569–575.

- Kwakkel, G.; Kollen, B.; Twisk, J. Impact of time on improvement of outcome after stroke. Stroke 2006, 37, 2348–2353.

- Wahl, A.S.; Omlor, W.; Rubio, J.C.; Chen, J.L.; Zheng, H.; Schroter, A.; Gullo, M.; Weinmann, O.; Kobayashi, K.; Helmchen, F.; et al. Neuronal repair. Asynchronous therapy restores motor control by rewiring of the rat corticospinal tract after stroke. Science 2014, 344, 1250–1255.

- Nishibe, M.; Urban, E.T., 3rd; Barbay, S.; Nudo, R.J. Rehabilitative training promotes rapid motor recovery but delayed motor map reorganization in a rat cortical ischemic infarct model. NeuroRehabilit. Neural Repair 2015, 29, 472–482.

- Zhang, L.; Xing, G.; Fan, Y.; Guo, Z.; Chen, H.; Mu, Q. Short- and Long-term Effects of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation on Upper Limb Motor Function after Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 1137–1153.

- Morizawa, Y.M.; Hirayama, Y.; Ohno, N.; Shibata, S.; Shigetomi, E.; Sui, Y.; Nabekura, J.; Sato, K.; Okajima, F.; Takebayashi, H.; et al. Reactive astrocytes function as phagocytes after brain ischemia via ABCA1-mediated pathway. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 28.

- Jorgensen, H.S.; Nakayama, H.; Raaschou, H.O.; Vive-Larsen, J.; Stoier, M.; Olsen, T.S. Outcome and time course of recovery in stroke. Part II: Time course of recovery. The Copenhagen Stroke Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1995, 76, 406–412.

- Duncan, P.W.; Lai, S.M.; Keighley, J. Defining post-stroke recovery: Implications for design and interpretation of drug trials. Neuropharmacology 2000, 39, 835–841.

- Obayashi, S.; Takahashi, R.; Onuki, M. Upper limb recovery in early acute phase stroke survivors by coupled EMG-triggered and cyclic neuromuscular electrical stimulation. NeuroRehabilitation 2020, 46, 417–422.

- Hsu, S.S.; Hu, M.H.; Wang, Y.H.; Yip, P.K.; Chiu, J.W.; Hsieh, C.L. Dose-response relation between neuromuscular electrical stimulation and upper-extremity function in patients with stroke. Stroke 2010, 41, 821–824.

- Page, S.J.; Levin, L.; Hermann, V.; Dunning, K.; Levine, P. Longer versus shorter daily durations of electrical stimulation during task-specific practice in moderately impaired stroke. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2012, 93, 200–206.

- Mann, G.E.; Burridge, J.H.; Malone, L.J.; Strike, P.W. A pilot study to investigate the effects of electrical stimulation on recovery of hand function and sensation in subacute stroke patients. Neuromodulation 2005, 8, 193–202.

- Barker, A.T. An introduction to the basic principles of magnetic nerve stimulation. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1991, 8, 26–37.

- Krewer, C.; Hartl, S.; Muller, F.; Koenig, E. Effects of repetitive peripheral magnetic stimulation on upper-limb spasticity and impairment in patients with spastic hemiparesis: A randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 95, 1039–1047.

- Beaulieu, L.D.; Schneider, C. Effects of repetitive peripheral magnetic stimulation on normal or impaired motor control. A review. Neurophysiol. Clin. 2013, 43, 251–260.

- Struppler, A.; Binkofski, F.; Angerer, B.; Bernhardt, M.; Spiegel, S.; Drzezga, A.; Bartenstein, P. A fronto-parietal network is mediating improvement of motor function related to repetitive peripheral magnetic stimulation: A PET-H2O15 study. Neuroimage 2007, 36 (Suppl. 2), T174–T186.

- Struppler, A.; Angerer, B.; Gundisch, C.; Havel, P. Modulatory effect of repetitive peripheral magnetic stimulation on skeletal muscle tone in healthy subjects: Stabilization of the elbow joint. Exp. Brain Res. 2004, 157, 59–66.

- Struppler, A.; Havel, P.; Muller-Barna, P. Facilitation of skilled finger movements by repetitive peripheral magnetic stimulation (RPMS)—A new approach in central paresis. NeuroRehabilitation 2003, 18, 69–82.

- Beaulieu, L.D.; Schneider, C. Repetitive peripheral magnetic stimulation to reduce pain or improve sensorimotor impairments: A literature review on parameters of application and afferents recruitment. Neurophysiol. Clin. 2015, 45, 223–237.

- Lindenberg, R.; Zhu, L.L.; Schlaug, G. Combined central and peripheral stimulation to facilitate motor recovery after stroke: The effect of number of sessions on outcome. NeuroRehabilit. Neural Repair 2012, 26, 479–483.