Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Evolutionary Biology

Microtubules (MTs) are major components of the eukaryotic cytoskeleton. Although MTs are involved in a variety of diverse processes ranging from intracellular transport to morphogenesis, their protein building blocks, called tubulins, are among the most well-conserved proteins. Tubulin is a subject of study in various fields of molecular science, from cell biology to evolution. Knowledge of the structure and function of tubulins has practical applications in the development of new drugs for medicine and agriculture.

- microtubules

- α-tubulins

- β-tubulins

- γ-tubulins

- phylogeny

- morphology and evolution of diatoms

1. Introduction

The tubulin superfamily includes α-, β-, γ-, δ-, ε-, ζ-, and η-tubulins [1]; the evolution of this superfamily has been shaped by intense recent duplications [2]. The high degree of similarity between the bacterial filamentous temperature-sensitive protein Z (FtsZ) and the eukaryotic family of tubulins [3][4] has led to the inclusion of FtsZ (along with other prokaryotic tubulin-like proteins [5]) in the tubulin superfamily [6][7], and FtsZ is thought to be a tubulin ancestor [8]. The α-, β- and γ-tubulins are present in all eukaryotic phyla, whereas δ-, ε-, ζ- and η-tubulins are restricted to animals, fungi and protists [9][10][11] and have been lost in some phyla [2]. Phylogenetic analysis has shown that plant α- and β-tubulins can be separated into distinct subclasses [12][13]. In animals, the α- and β-tubulin genes have undergone duplication, encoding separate isoforms [14][15]. The various isoforms of α-, β- and γ-tubulins differ by their variable sites [16][17] mostly at the C-terminal ends, and the different isoform structures affect MT dynamics [18][19]. In addition to these duplications, the diversity of tubulin isoforms can be further increased by the application of post-translational modifications [5][17].

α- and β-tubulin monomers form a dimeric protein that serves as a basic building block for microtubules [7][9], and γ-tubulin is necessary to initiate their assembly [9][20][21]. Although the three-dimensional structure of the tubulin dimer has been studied [22][23][24][25][26][27], the roles played by some amino acid residues in both the α- and β-tubulin chains in model organisms are known [24].

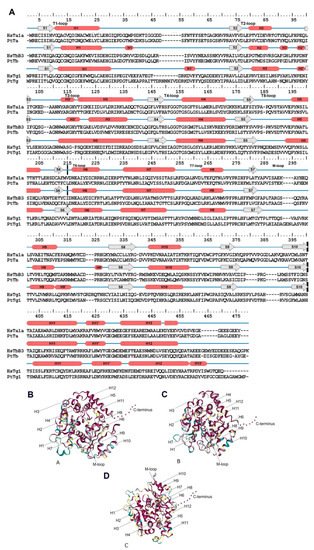

For example, it is known that α- and β-tubulins consist of 10 β-chains (S1–S10) and 12 α-helices (H1–H12) connected by loops. These structures formed by three major domains: an N-terminal nucleotide-binding domain (1–205 amino acids [a.a.]), an intermediate domain (206–381 a.a.) and a C-terminal ligand-binding domain (from 382 a.a.; Figure 1) [19][28][29][30]. γ-tubulins have similar structure according to [31][32]. The C-terminal domain is also known as the C-terminal tail (CTT) [13], and its modifications affect protein diffusion along MTs [33] and alter dynein binding [12]. Amino acid substitutions in CTT may result in changes in protein function since this domain is responsible for interactions between microtubules and various intracellular components [12][34]. Tubulin heterodimers assemble longitudinally to form protofilaments. The H3-helice and M-loop (ML-surface) are involved in lateral interactions between heterodimers of neighboring protofilaments [35][36].

Figure 1. Tubulin structure. (A): Secondary structure for α- and b-tubulin for example H. sapiens (HsTa1A—α-tubulins, HsTb3—β-tubulins and HsTg1—γ-tubulin) and P. tricornutum (PtTa—α-tubulins, PtTb—β-tubulins and PtTg1—γ-tubulin). β-chains are marked S1–S10 and 12 α-helices—H1–H12. Cross black lines delimit major domains. (B–D): Structural conservation mapping performing on the ConSurf 2016 webserver; this conservation was assayed for all diatom tubulins. (B): α-tubulins; (C): β-tubulins; (D): γ-tubulins. Conserved amino acid residues are shown in shades of red, and the variable amino acids are showed in shades of blue. Residues with insufficient data are showed in shades of yellow.

Diatoms are a unicellular eukaryotic group within the kingdom Chromista [37] that display a high diversity of morphologically distinct species [38]. The phylum Bacillariophyta consists of classes Coscinodiscophyceae (centric species with radial symmetry), Mediophyceae (centric species with radial and bipolar symmetry), and the bilaterally symmetric class Bacillariophyceae. Class Bacillariophyceae, in turn, consists of the subclass Bacillariophycidae (raphid pennates) and the araphid subclasses Fragilariophycidae and Urneidophycidae. Phylogenetic analysis of 4 markers expressed by araphid diatoms can be used to separate them into two major clades: (1) a small basal araphid clade, which includes families from Urneidophycidae and the genera Neofragilaria and Asteroplanus; and (2) a larger Fragilariophycidae clade, which includes other araphid pennates. This latter clade is thought to be a sister of the raphid pennates [39][40]. According to the timescale for diatom evolution based on four molecular markers [39][41], class Coscinodiscophyceae diverged from the remaining diatoms belonging to the subdivision Bacillariophytina 230 Ma (max). Within the Bacillariophytina the bi(multi)- polar centric class Mediophyceae diverged from the class Bacillariophyceae 218 Ma. The Bacillariophyceae radiated 190 Ma.

Numerous studies have attempted to determine the genetic and cellular mechanisms that underlie the differences in symmetry and the fine structures of diatom cell walls. Earlier studies have shown that this group of organisms expresses α-, β-, and γ-tubulins [2][42][43][44]. Exposure to microtubule inhibitors causes a variety of structural anomalies in diatom valves [45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54]. In other studies, tubulin has been shown to be involved during morphogenesis, and microtubules appear to form underlying layers during the formation of valves [55][56] and other specialized structures [51][52]. The role of microtubules is likely not limited to defining formations of structure; they are also likely to be involved in intracellular vesicular transport [45][57][58]. A hypothesis was put forward about the specific localization of aquaporins in silicalemma by MTs during the morphogenesis of silica structures [59].

2. Features of Diatom Tubulin a.a. Sequences

Tubulins are highly conserved, and the substitution of a single amino acid in these protein sequences can cause microtubule dysfunction and phenotypic changes [15][60]. Various tubulin isoforms are known to exist in nature [5][61], some of which have undergone subfunctionalization [12][62]. However, mutagenesis represents an essential tool in the search for novel approaches to the treatment of microtubule-related diseases [18][63].

Diatom genomes and transcriptomes have been found to encode α-, β- and γ-tubulins (Supplemental Table S1), as described by previous studies [2][42][43][44]. Only a few species appear to express γ-tubulin, although it is present in all genomes studied, which is likely due to the relatively low expression level of γ-tubulin compared with the α- and β-tubulins. γ-tubulin is a vital part of the acentriolar microtubule organization centre (MTOC) present in diatoms [42]. As this structure is only duplicated at certain stages of the cell cycle, γ-tubulin may not be expressed at other times, and thus not present in transcriptomic datasets. To collect more diatom γ-tubulin sequences, it is necessary to produce either genomic sequences or transcriptomes from synchronized cultures during MTOC duplication. It is likely that such datasets for all diatom species will include γ-tubulins. Long insertions in the T1-T2 nucleotide binding domain and the beginning of the second domain may be characteristic of diatom γ-tubulins (S5_Alignment3_Gamma_diatoms.fas). It is possible, however, that these insertions are removed during protein maturation.

Most amino acid substitutions identified within the diatom α- and β-tubulin sequences were found in the N-terminal domain and the CTT. The CTT is known to be positioned outside of the microtubule core and serves as a binding site for some microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) [64][65]. The CTT has also been shown to undergo various modifications [34]. In addition, the CTT domain affects microtubule polymerization and depolymerization kinetics [28]. It was suppose that the substitutions identified within this domain may affect some of these properties and the overall function of the microtubule apparatus. Insertions in this region have previously been shown to cause the repositioning of essential amino acids involved in GTP binding [66].

Tubulins are subject to numerous posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation [67], acetylation [6][68], methylation [69], palmitoylation [70][71], ubiquitylation [72] polyamination [73], and detyrosination/tyrosination [74]. It was considered it crucial to study whether the sites of these modifications are preserved in diatom tubulin sequences. It was noted above that K40 in H. sapiens α-tubulin was an important modification site. Acetylation in this position protects microtubules from aging [75]. According to our results, this site is only preserved in the diatom group α1, and replaced with incompatible amino acids in other groups. Moreover, our findings revealed that in 93% of sequences, this site is preserved in the diatom group α1 and is absent in the group α4, which may affect the stability of the microtubules. It is likely that acetylation at this position is most significant for the α1 group. This suggests that, at least outside α1, microtubule longevity is either much lower than in humans, or regulated via a different mechanism.

Unlike K40, the C-terminal tyrosine and detyrosination site [74] and the glutamination and polyglutamination sites [76] are essential for microtubule flexibility and various microtubule-regulating signals. These sites are conserved for all diatoms (assuming that E-to-D substitutions are synonymous), pointing to an important role to microtubule functioning. Nevertheless, despite the synonymy of these amino acids, their substitution in some cases is still significant for the regulation of the properties of microtubules through glutamination [77]. It is possible that tyrosine phosphorylation site (Y432) [65] and lysine ubiquitination site (K304) [72] also retain their role. The site palmitoylation [70], a target of growth factor in human cells, is retained in all diatom α-tubulin groups. Low identity of this position in other groups suggests that growth factor is not an important microtubule regulator in diatoms. On the other hand, rigidity regulation mechanism involving K60 and H283 [75] is possible in diatoms, since these amino acids are conserved.

Most of β-tubulin modification sites are conserved (Supplemental Table S7b), suggesting that diatom β-tubulin regulation is similar with other organisms [68][73][78]. The only exception is provided by polyglycylation sites (E435 [79] and E438 [80]) which are more variable (Supplemental Table S7b).

Only two phosphorylation sites are in diatom γ-tubulins, namely S131 and T288, but four phosphorylation sites (S80, S131, T288, and S361 [81]) are known among other organisms. Positions to be homologous to S80 and S361 contain entirely different amino acids (aminomonocarbonic alanine and glycine instead of oxymonoaminocarbonic serine). As the radicals of these amino acids are chemically different, they could not serve as phosphorylation sites. However, these positions are conserved between diatom γ-tubulin groups, hinting to their importance for some other function.

3. Diatom Tubulin Structure and Evolution

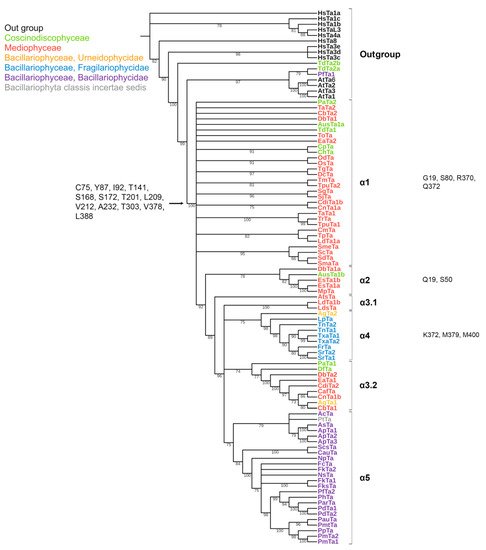

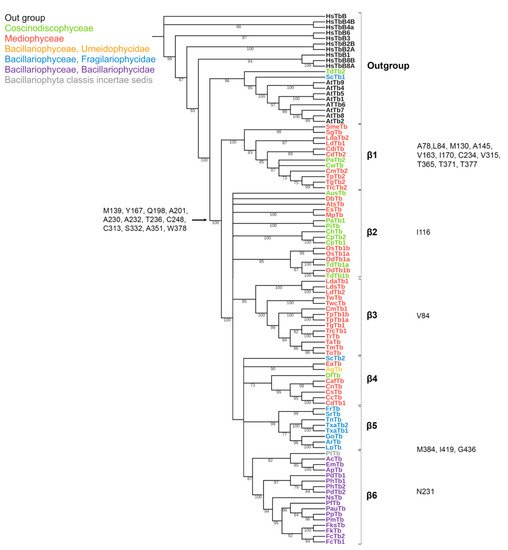

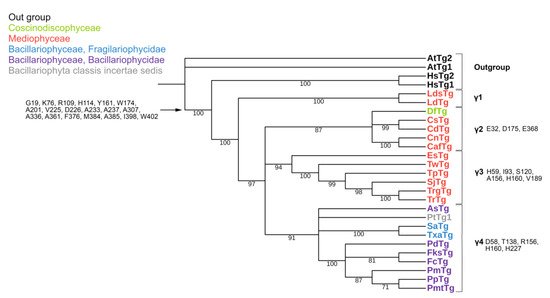

The conserved a.a. identified in the predicted sequences showed that there was common a.a. for all groups, while almost every group contained a.a. characteristic only for their group (Supplemental Table S6A–C). A comparison of phylogenetic reconstructions (Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4) and these conserved a.a. positions in diatoms showed that changes occurred in the primary structure of proteins from one phylogenetic group of tubulins to another. However, there were distinctive amino acids that were not conserved. This finding clearly confirms that each of the tubulin classes had an ancestral form in which some of the positions were formed and supported by selection. Thus, for α-tubulins, these are C75, Y87, I92, T141, S168, S172, T201, L209, V212, A232, T303, V378, L388, and A400 (Supplemental File S3, Supplemental Table S6A; Figure 2). β-tubulins have 12 such positions: M139, Y167, Q198, A201, A230, A232, T236, C248, C313, S323 A351, W378 (Supplemental File S4; Supplemental Table S6B; Figure 3), while such positions have γ-tubulins nineteen, but there are too few data on this tubulin class and changes may occur with an increase in the sample (Supplemental File S5, Supplemental Table S6C; Figure 4). In all tubulin classes, the groups of pennate species, which are the youngest in the evolution of diatoms (α5, β5, β6, and γ4), have the maximum difference. In β-tubulins, of the 31 positions that was identified in this work for the β1 group, 12 positions in β6 are retained in the evolutionarily subsequent groups. A.a. that were most supported by selection during the diatom evolution were indicated in phylogenetic reconstructions (Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4). Since some of these a.a. occurred in evolutionarily older α1 and β1, and some, upon the emergence of subsequent groups and are supported in younger ones, it was assumed that they may be of functional importance and, possibly, are one of the factors influencing the species-specificity of tubulins and their role in the morphogenesis of diatoms. This conclusion is also confirmed by a division of tubulins between centric (classes Coscinodiscophyceae and Mediophyceae) and pennate (class Bacillariophyceae) diatoms.

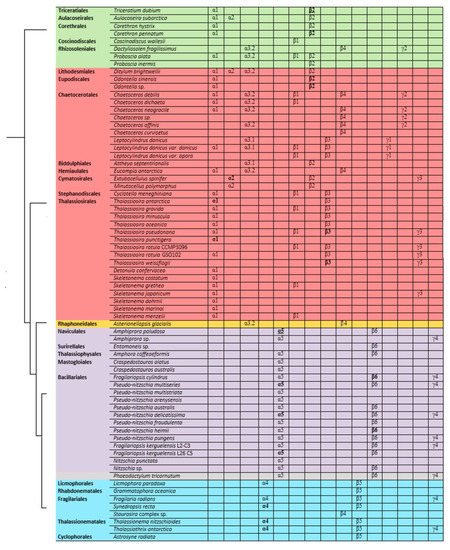

Figure 2. Phylogenetic tree of diatom α-tubulins. A total of 101 sequences were used to build a Maximum Likelihood tree using the LG + F + R7 substitution model. The amino acids conserved in diatoms are on the left , characteristic amino acids of certain α-tubulin groups are on the right. Large taxa are highlighted in color: green, Coscinodiscophyceae; red, Mediophyceae; blue, Bacillariophyceae, Fragilariophycidae; orange, Bacillariophyceae, Urneidophycidae; purple, Bacillariophyceae, Bacillariophycidae.

Figure 3. Phylogenetic tree of diatom β-tubulins. A total of 106 sequences were used to build a Maximum Likelihood tree using the LG + F + R7 substitution model. The amino acids conserved in diatoms are on the left, characteristic amino acids of certain β-tubulin groups are on the right. Large taxa are highlighted in color: green, Coscinodiscophyceae; red, Mediophyceae; blue, Bacillariophyceae, Fragilariophycidae; orange, Bacillariophyceae, Urneidophycidae; purple, Bacillariophyceae, Bacillariophycidae.

Figure 4. Phylogenetic tree of diatom γ-tubulins. A total of 40 sequences were used to build aMaximum Likelihood tree using the LG + F + I + G4 substitution model. The amino acids conserved in diatoms are on the left, characteristic amino acids of certain γ-tubulin groups are on the right. Large taxa are highlighted in color: green, Coscinodiscophyceae; red, Mediophyceae; blue, Bacillariophyceae, Fragilariophycidae; purple, Bacillariophyceae, Bacillariophycidae.

In γ-tubulins, due to the small sample of sequences, it is difficult to reliably identify conserved a.a. positions. However, even in this case, there is a noticeable difference in the composition of conserved a.a. more evolutionarily earlier and later groups. Thus, it can suppose that during the evolution of diatom tubulins, some amino acid residues were formed that are characteristic of individual groups of a certain systematic position. In the absence of experimental data, it cannot presume the function of each of them; however, it believe that maintaining conservatism in these positions may indirectly indicate their functional significance.

Based on the identified diversity of tubulin groups and the analysis of the a.a. sequences, it was assumed that tubulins of diatoms evolved independently (Figure 5). Diatoms with radial symmetry from class Coscinodiscophyceae, the earliest class, contain three α-tubulin groups (α1, α2, and α3), three β-tubulin groups (β1, β2, and β4), and a single γ2-tubulin group. The class Mediophyceae appears later, inheriting the same three Coscinodiscophyceaeα-tubulin groups (α1–α3), four β-tubulin groups (β1–β4), and three γ-tubulin groups (γ1–γ3). Our dataset includes only one species from the subclass Urneiophycidae (basal araphids), Asterionellopsis glacialis. This species has inherited the α3 and α4 groups of α-tubulin and the β4 group of β-tubulin and acquired the α4 group of α-tubulin during its evolution. The divergence of Urneiophycidae was followed by the formation of the class Bacillariophyceae, subclass Bacillariophycidae, in which all previously presented tubulin groups disappeared and new α5, β6, and γ4 tubulin groups surfaced. The youngest diatoms core araphids from the subclass Fragilariophycidae inherited the α4 group of α-tubulin, β4 and β5 groups of β-tubulin, and γ4 group of γ-tubulin.

Figure 5. General scheme of evolution of α-, β-, and γ-tubulin in diatoms. Species names are placed according to [39]. Groups that have two copies within a given organism are highlighted in bold, and groups that have three copies are in bold and underlined.

The analysis performed allows us to trace changes in the structure of tubulin in diatoms. The presence in the same genomes of some species of different groups of α- and β-tubulins (Leptocylindrus danicus, T. pseudonana) confirms their independent evolution in diatoms of the class Mediophyceae. It is possible that some tubulins of certain groups as a result of duplication could acquire different properties, which subsequently led to the formation of a new tubulin group. The most surprising results regard the diatom species of the class Bacillariophyceae (Figure 5). For this class, the evolution of α-tubulins becomes dependent and excludes the presence of two groups of tubulins. It is noted that the diatom species of the class Bacillariophyceae (Figure 5) are characterized by the presence of only one group of α-, β-, or γ-tubulins. Most likely, the absence of any variations in tubulins in the Bacillariophyceae diatom genomes indicates the need for compatibility of the α- and β-tubulins. Thus, diatom tubulins could evolve both concurrently between α- and β-tubulins (Bacillariophyceae), as suggested for insect tubulins [82], and independently (Mediophyceae), which was previously shown [2].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms23020618

References

- Dutcher, S.K. The tubulin fraternity: Alpha to eta. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2001, 13, 49–54.

- Findeisen, P.; Mühlhausen, S.; Dempewolf, S.; Hertzog, J.; Zietlow, A.; Carlomagno, T.; Kollmar, M. Six subgroups and extensive recent duplications characterize the evolution of the eukaryotic tubulin protein family. Genome Biol. Evol. 2014, 6, 2274–2288.

- Dyer, N. Tubulin and its prokaryotic homologue FtsZ: A structural and functional comparison. Sci. Prog. 2009, 92, 113–137.

- Löwe, J.; Amos, L.A. Crystal structure of the bacterial cell-division protein FtsZ. Nature 1998, 391, 203–206.

- Ludueña, R.F.; Shooter, E.M.; Wilson, L. Structure of the tubulin dimer. J. Biol. Chem. 1977, 252, 7006–7014.

- L’Hernault, S.W.; Rosenbaum, J.L. Chlamydomonas alpha-tubulin is posttranslationally modified by acetylation on the epsilon-amino group of a lysine. Biochemistry 1985, 24, 473–478.

- Ludueña, R.F. Are tubulin isotypes functionally significant. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1993, 4, 445–457.

- Michie, K.A.; Monahan, L.G.; Beech, P.L.; Harry, E.J. Trapping of a spiral-like intermediate of the bacterial cytokinetic protein FtsZ. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 1680–1690.

- McKean, P.G.; Vaughan, S.; Gull, K. The extended tubulin superfamily. J. Cell Sci. 2001, 114, 2723–2733.

- Oakley, B.R. An abundance of tubulins. Trends Cell Biol. 2000, 10, 537–542.

- Zhao, Z.; Liu, H.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, S.; An, L.; Wang, C.; Jin, Q.; Zhou, M.; Xu, J.-R. Molecular evolution and functional divergence of tubulin superfamily in the fungal tree of life. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6746.

- Hashimoto, T. Dissecting the cellular functions of plant microtubules using mutant tubulins. Cytoskeleton 2013, 70, 191–200.

- Breviario, D.; Gianì, S.; Morello, L. Multiple tubulins: Evolutionary aspects and biological implications. Plant J. 2013, 75, 202–218.

- Elliott, E.M.; Henderson, G.; Sarangi, F.; Ling, V. Complete sequence of three alpha-tubulin cDNAs in Chinese hamster ovary cells: Each encodes a distinct alpha-tubulin isoprotein. Mol. Cell Biol. 1986, 6, 906–913.

- Good, P.J.; Richter, K.; Dawid, I.B. The sequence of a nervous system-specific, class II beta-tubulin gene from Xenopus laevis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989, 17, 8000.

- Ludueña, R.F. Multiple forms of tubulin: Different gene products and covalent modifications. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1997, 178, 207–275.

- Ludueña, R.F. A hypothesis on the origin and evolution of tubulin. Int. Rev. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2013, 302, 41–185.

- Prassanawar, S.S.; Panda, D. Tubulin heterogeneity regulates functions and dynamics of microtubules and plays a role in the development of drug resistance in cancer. Biochem. J. 2019, 476, 1359–1376.

- Vemu, A.; Atherton, J.; Spector, J.O.; Moores, C.A.; Roll-Mecak, A. Tubulin isoform composition tunes microtubule dynamics. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2017, 28, 3564–3572.

- Dutcher, S.K. Long-lost relatives reappear: Identification of new members of the tubulin superfamily. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2003, 6, 634–640.

- Horio, T.; Uzawa, S.; Jung, M.K.; Oakley, B.R.; Tanaka, K.; Yanagida, M. The fission yeast gamma-tubulin is essential for mitosis and is localized at microtubule organizing centers. J. Cell Sci. 1991, 99, 693–700.

- Gigant, B.; Curmi, P.A.; Martin-Barbey, C.; Charbaut, E.; Lachkar, S.; Lebeau, L.; Siavoshian, S.; Sobel, A.; Knossow, M. The 4 Å X-ray structure of a tubulin: Stathmin-like domain complex. Cell 2000, 102, 809–816.

- Li, H.; DeRosier, D.J.; Nicholson, W.V.; Nogales, E.; Downing, K.H. Microtubule structure at 8 Å resolution. Structure 2002, 10, 1317–1328.

- Löwe, J.; Li, H.; Downing, K.H.; Nogales, E. Refined structure of αβ-tubulin at 3.5 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 313, 1045–1057.

- Sept, D.; Baker, N.A.; McCammon, J.A. The physical basis of microtubule structure and stability. Protein Sci. 2003, 12, 2257–2261.

- Howes, S.C.; Geyer, E.A.; LaFrance, B.; Zhang, R.; Kellogg, E.H.; Westermann, S.; Rice, L.M.; Nogales, E. Structural and functional differences between porcine brain and budding yeast microtubules. Cell Cycle 2018, 17, 278–287.

- Mghlethaler, T.; Gioia, D.; Prota, A.E.; Sharpe, M.E.; Cavalli, A.; Steinmetz, M.O. Comprehensive analysis of binding sites in tubulin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 13331–13342.

- Freedman, H.; Luchko, T.; Luduena, R.F.; Tuszynski, J.A. Molecular dynamics modeling of tubulin C-terminal tail interactions with the microtubule surface. Proteins 2011, 79, 2968–2982.

- Keskin, O.; Durell, S.R.; Bahar, I.; Jernigan, R.L.; Covell, D.G. Relating molecular flexibility to function: A case study of tubulin. Biophys J. 2002, 83, 663–680.

- Nogales, E.; Wolf, S.G.; Downing, K.H. Structure of the αβ-tubulin dimer by electron crystallography (Correction). Nature 1998, 393, 191.

- de Pereda, J.M.; Leynadier, D.; Evangelio, J.A.; Chacon, P.; Andreu, J.M. Tubulin secondary structure analysis, limited proteolysis sites, and homology to FtsZ. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 14203–14215.

- Chumová, J.; Kourová, H.; Trögelová, L.; Daniel, G.; Binarov, P. γ-tubulin complexes and fibrillar arrays: Two conserved high molecular forms with many cellular functions. Cells 2021, 10, 776.

- Bigman, L.S.; Levy, Y. Tubulin tails and their modifications regulate protein diffusion on microtubules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 8876–8883.

- Parrotta, L.; Cresti, M.; Cai, G. Accumulation and post-translational modifications of plant tubulins. Plant Biol. 2014, 16, 521–527.

- Borys, F.; Joachimiak, E.; Krawczyk, H.; Fabczak, H. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors affecting microtubule dynamics in normal and cancer cells. Molecules 2020, 25, 3705.

- Nogales, E.; Whittaker, M.; Milligan, R.A.; Downing, K.H. High-resolution model of the microtubule. Cell 1999, 96, 79–88.

- Cavalier-Smith, T. Kingdom Chromista and its eight phyla: A new synthesis emphasizing periplastid protein targeting, cytoskeletal and periplastid evolution, and ancient divergences. Protoplasma 2018, 255, 297–357.

- Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. AlgaeBase World-Wide Electronic Publication; National University of Ireland: Galway, Ireland, 2021.

- Medlin, L.K.; Desvidevises, Y. Phylogeny of ‘araphid’ diatoms inferred from SSU and LSU rDNA, rbcl and psbA sequences. Vie Milieu. 2016, 66, 129–154.

- Sato, S. Phylogeny of Araphid Diatoms Inferred from Morphological and Molecular Data. Ph.D. Thesis, Univiversity Bremen, Bremen, Germany, 2008.

- Medlin, L.K. A timescale for diatom evolution based on four molecular markers: Reassessment of ghost lineages and major steps defining diatom evolution. Vie Milieu 2015, 65, 219–238.

- Armbrust, E.V. Structural features of nuclear genes in the centric diatom Thalassiosira weissflogii (Bacillariophyceae). J. Phycol. 2000, 36, 942–946.

- Aumeier, C. The Cytoskeleton of Diatoms Structural and Genomic Analysis. Doctoral Thesis, Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, Bonn, Germany, 2012.

- De Martino, A.; Amato, A.; Bowler, C. Mitosis in diatoms: Rediscovering an old model for cell division. Bioassays 2009, 31, 874–884.

- Bedoshvili, Y.; Gneusheva, K.; Popova, M.; Morozov, A.; Likhoshway, Y. Anomalies in the valve morphogenesis of the centric diatom alga Aulacoseira islandica caused by microtubule inhibitors. Biol. Open 2018, 7, bio035519.

- Blank, G.; Sullivan, C. Diatom mineralization of silicon acid. VI. The effects of microtubule inhibitors on silicic acid metabolism in Navicula saprophila. J. Phycol. 1983, 19, 39–44.

- Blank, G.; Sullivan, C. Diatom mineralization of silicon acid. VII. Influence of microtubule drugs on symmetry and pattern formation in valves of Navicula saprophila during morphogenesis. J. Phycol. 1983, 19, 294–301.

- Cohn, S.; Nash, J.; Pickett-Heaps, J. The effects of drugs on diatom valve morphogenesis. Protoplasma 1989, 149, 130–143.

- Kharitonenko, K.V.; Bedoshvili, Y.D.; Likhoshway, Y.V. Changes in the micro-and nanostructure of siliceous valves in the diatom Synedra acus under the effect of colchicine treatment at different stages of the cell cycle. J. Struct. Biol. 2015, 190, 73–80.

- Oey, J.L.; Schnepf, E. Uber die Auslösung der Valvenbildungbei der Diatomee Cyclotella cryptica. Arch. Mikrobiol. 1970, 71, 199–213.

- Van de Meene, A.; Pickett-Heaps, J. Valve morphogenesis in the centric diatom Proboscia alata Sundström. J. Phycol. 2002, 38, 351–363.

- Van de Meene, A.; Pickett-Heaps, J. Valve morphogenesis in the centric diatom Rhizosolenia setigera (Bacillariophyceae, Centrales) and its taxonomic implications. Eur. J. Phycol. 2004, 39, 93–104.

- Tesson, B.; Hildebrand, M. Extensive and intimate association of the cytoskeleton with forming silica in diatoms: Control over patterning on the meso- and micro-scale. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e14300.

- Tesson, B.; Hildebrand, M. Dynamics of silica cell wall morphogenesis in the diatom Cyclotella cryptica: Substructure formation and the role of microfilaments. J. Struct. Biol. 2010, 169, 62–74.

- Murphy, S.M.; Urbani, L.; Stearns, T. The mammalian gamma-tubulin complex contains homologues of the yeast spindle pole body components spc97p and spc98p. J. Cell Biol. 1998, 141, 663–674.

- Murphy, S.M.; Preble, A.M.; Patel, U.K.; O’Connell, K.L.; Dias, D.P.; Moritz, M.; Agard, D.; Stults, J.T.; Stearns, T. GCP5 and GCP6: Two new members of the human gamma-tubulin complex. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001, 12, 3340–3352.

- Bedoshvili, Y.D.; Gneusheva, K.V.; Popova, M.S.; Avezova, T.N.; Arsentyev, K.Y.; Likhoshway, Y.V. Frustule morphogenesis of raphid pennate diatom Encyonema ventricosum (Agardh) Grunow. Protoplasma 2018, 255, 911–921.

- Parkinson, J.; Brechet, Y.; Gordon, R. Centric diatom morphogenesis: A model based on a DLA algorithm investigating the potential role of microtubules. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1452, 89–102.

- Grachev, M.A.; Annenkov, V.V.; Likhoshway, Y.V. Silicon nanotechnologies of pigmented heterokonts. BioEssays 2008, 30, 328–337.

- Heale, K.A.; Alisaraie, L. C-terminal tail of β-tubulin and its role in the alterations of dynein binding mode. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2020, 78, 331–345.

- Stearns, T.; Evans, L.; Kirschner, M. γ-tubulin is a highly conserved component of the centrosome. Cell 1991, 65, 825–836.

- Nguyen, L.T.; Schmidt, H.A.; Von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274.

- Giannakakou, P.; Gussio, R.; Nogales, E.; Downing, K.H.; Zaharevitz, D.; Bollbuck, B.; Poy, G.; Sackett, D.; Nicolaou, K.C.; Fojo, T. A common pharmacophore for epothilone and taxanes: Molecular basis for drug resistance conferred by tubulin mutations in human cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 2904–2909.

- Maccioni, R.B.; Rivas, C.I.; Vera., J.C. Differential interaction of synthetic peptides from the carboxyl-terminal regulatory domain of tubulin with microtubule-associated proteins. EMBO J. 1988, 7, 1957–1963.

- Paschal, B.M.; Obar, R.A.; Vallee, R.B. Interaction of brain cytoplasmic dynein and MAP2 with a common sequence at the C terminus of tubulin. Nature 1989, 342, 569–572.

- Ma, C.; Li, C.; Ganesan, L.; Oak, J.; Tsai, S.; Sept, D.; Morrissette, N.S. Mutations in α-tubulin confer dinitroaniline resistance at a cost to microtubule function. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007, 18, 4711–4720.

- Hargreaves, J.; Wandosell, F.; Avila, J. Phosphorylation of tubulin enhances its interaction with membranes. Nature 1986, 323, 827–828.

- Chu, C.W.; Hou, F.; Zhang, J.; Phu, L.; Loktev, A.V.; Kirkpatrick, D.S.; Jackson, P.K.; Zhao, Y.; Zou, H. A novel acetylation of beta-tubulin by San modulates microtubule polymerization via down-regulating tubulin incorporation. Mol. Biol. Cell 2011, 22, 448–456.

- Park, I.Y.; Powell, R.T.; Tripathi, D.N.; Dere, R.; Ho, T.H.; Blasius, T.L.; Chiang, Y.C.; Davis, I.J.; Fahey, C.C.; Hacker, K.E.; et al. Dual chromatin and cytoskeletal remodeling by SETD2. Cell 2016, 166, 950–962.

- Ozols, J.; Caron, J.M. Posttranslational modification of tubulin by palmitoylation: II. Identification of sites of palmitoylation. Mol. Biol. Cell 1997, 8, 637–645.

- Zambito, M.; Wolff, J. Palmitoylation of tubulin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 239, 650–654.

- Wang, Q.; Peng, Z.; Long, H.; Deng, X.; Huang, K. Polyubiquitylation of alpha- tubulin at K304 is required for flagellar disassembly in Chlamydomonas. J. Cell Sci. 2019, 132, jcs229047.

- Song, Y.; Kirkpatrick, L.L.; Schilling, A.B.; Helseth, D.L.; Chabot, N.; Keillor, J.W.; Johnson, G.V.; Brady, S.T. Transglutaminase and polyamination of tubulin: Posttranslational modification for stabilizing axonal microtubules. Neuron 2013, 78, 109–123.

- Eshun-Wilson, L.; Zhang, R.; Portran, D.; Nachury, M.V.; Toso, D.B.; Löhr, T.; Vendruscolo, M.; Bonomi, M.; Fraser, J.S.; Nogales, E. Effects of alpha-tubulin acetylation on microtubule structure and stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 10366–10371.

- Nieuwenhuis, J.; Adamopoulos, J.A.; Bleijerveld, O.B.; Mazouzi, A.; Stickel, E.; Celie, P.; Altelaar, M.; Knipscheer, P.; Perrakis, A.; Blomen, V.A.; et al. Vasohibins encode tubulin detyrosinating activity. Science 2017, 358, 1453–1456.

- Eddé, B.; Rossier, J.; Le Caer, J.P.; Desbruyères, E.; Gros, F.; Denoulet, P. Posttranslational glutamylation of alpha-tubulin. Science 1990, 247, 83–85.

- Wloga, D.; Rogowski, K.; Sharma, N.; Van Dijk, J.; Janke, C.; Eddé, B.; Bré, M.H.; Levilliers, N.; Redeker, V.; Duan, J.; et al. Glutamylation on alpha-tubulin is not essential but affects the assembly and functions of a subset of microtubules in Tetrahymena thermophila. Eukaryot Cell. 2008, 7, 1362–1372.

- Ori-McKenney, K.M.; McKenney, R.J.; Huang, H.H.; Li, T.; Meltzer, S.; Jan, L.Y. Phosphorylation of β tubulin by the Down syndrome kinase, Minibrain/DYRK1a, regulates microtubule dynamics and dendrite morphogenesis. Neuron 2016, 90, 551–563.

- Rüdiger, M.; Plessman, U.; Kloppel, K.D.; Wehland, J.; Weber, K. Class II tubulin, the major brain beta tubulin isotype is polyglutamylated on glutamic acid residue 435. FEBS Lett. 1992, 308, 101–105.

- Alexander, J.E.; Hunt, D.F.; Lee, M.K.; Shabanowitz, J.; Michel, H.; Berlin, S.C.; MacDonald, T.L.; Sundberg, R.J.; Rebhun, L.I.; Frankfurter, A. Characterization of posttranslational modifications in neuron- specific class III beta- tubulin by mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 4685–4689.

- Teixidó-Travesa, N.; Roig, J.; Lüders, J. The where, when and how of microtubule nucleation—one ring to rule them all. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125 Pt 19, 4445–4456.

- Nielsen, M.G.; Gadagkar, S.R.; Gutzwiller, L. Tubulin evolution in insects: Gene duplication and subfunctionalization provide specialized isoforms in a functionally constrained gene family. BMC Evol. Biol. 2010, 10, 113.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!