Gamification allows for the implementation of experiences that simulate the design of (video) games, giving individuals the opportunity to be the protagonists in them. Its inclusion in the educational environment responds to the need to adapt teaching–learning processes to the characteristics of homo videoludens, placing value once again on the role of playful action in the personal development of individuals.

- gamification

- teacher training

- gamification design frameworks

1. Introduction

2. Models of Instructional Design in Gamification

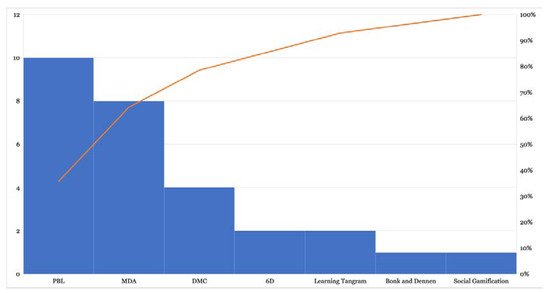

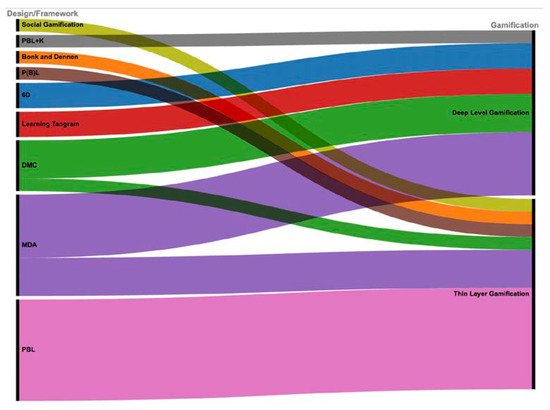

The instructional design model with the greatest relevance is the PBL or points, badges, and leaderboards strategy with 35.71%, including variants such as PBL+K and PL. In second place, we see the MDA or mechanics, dynamics & aesthetics architecture, with 28.57% presence. This is followed by Pyramid DMC or dynamics, mechanics and components with 14.28%. With the same percentages (7.14%) are the 6D approach and Learning Tangram. Finally, the Bonk and Dennen model, as well as the social gamification approach, also with the same proportion (3.57%). It should also be noted that the PBL and MDA instructional design models are present in more than 50% of the sample (Figure 5).

3. Effects of Gamified Practices in the Teaching–learning Process

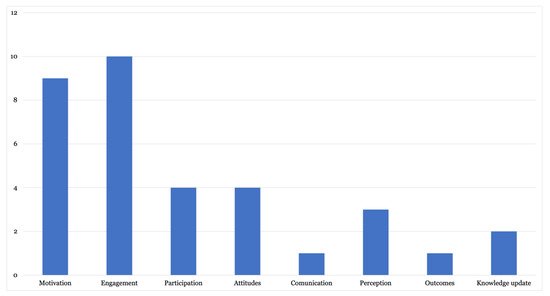

As can be seen in Figure 7, engagement or educational commitment is one of the main implications of gamification in educational practice identified in the sample, with 29.41%. Next, the impact of gamification processes on student motivation is evident (26.47%) through an increase in motivation. Based on the practice of Pérez-López et al. [40], gamification, as a methodological strategy, creates an improvement in student motivation and an increase in their involvement. With the same percentage (11.77%), there are results related to student participation and attitudes, as a consequence of the previous elements. Likewise, an improvement in the students’ perception of the knowledge acquired has been identified (8.82%) [41], followed by aspects related to the updating of pedagogical, technological, and conceptual knowledge, as a consequence of ongoing teacher training (5.88%) [42]. Finally, with the same percentage (2.94%), results related to the improvement of communication and academic results of participating students were observed.

3. Conclusions

Study has made it possible to identify the main instructional design models for gamification systems. For this purpose, it has been necessary to establish a relationship with elements implemented in the practices proposed, since in many cases the model involved in the design of the gamified practice has not been explicitly established. In this sense, coinciding with the study by Navarro-Mateos et al. [17], there is a general lack of knowledge of the process of gamification systems or specific models of instructional design by teachers, causing the introduction of gamification elements without a specific criterion or without a configuration that has a specific purpose.

The prevalence of PBL, i.e., gamification practices that introduce, in isolation, three components: points, badges and leaderboards. Although other studies [17] dismissed those gamification proposals based on PBL, considering that gamification “is a more abstract, complex and strategic process that aims to go beyond the use of points, badges and rankings” (p. 512), the reality is that it represents one of the most widely used gamification models in the field of instructional design [1,10,12,43,44]. However, other more complex models have been identified that require a more reflective and elaborate design process, resulting in deep gamification systems, such as the MDA architecture, coinciding with the study conducted by Bozkurt and Durak [3], the Elements Pyramid and the 6D approach.

In relation to the educational implications of gamification in the teaching–learning processes, through the proposals analyzed in the articles that make up the sample, a direct relationship between this methodology and increase in motivation, commitment, participation, and attitudes of the participating students has been evidenced. Conclusions that can also be observed in other studies [5,10,12,17,44], which identify a series of implications of gamification at all educational levels, are those such as improved academic performance and increased student engagement and motivation. Pegalajar Palomino [15] states that, “at the cognitive level, it is worth noting how the practice of gamified learning experiences allows an improvement in the academic performance of students, helping them to maximize learning” (p. 178).

There is an adequate educational approach to gamification requires a deep knowledge of the implications derived from the implementation of this methodology. To this end, it is necessary to assess the importance of instructional design models that allow an adequate development of gamified practices. The interconnection of elements that make up a system of these characteristics requires a process of reflection, planning, and arrangement of its components, avoiding improvisation and arbitrariness.

Educational implications, which aim to go beyond the improvement of students’ academic performance, pursue an increase in motivation, commitment, and positive attitude towards the teaching–learning process itself, through the entertainment and uniqueness provided by gamified practices. It also becomes necessary to implement experiences in the field of teacher training, both in its initial and permanent stage, providing experiential learning that allows teachers to introduce, in their professional development, this methodology in a relevant way, based on their own experience.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/educsci12010044