Preterm infants have long-term healthcare needs. Oral feeding competency in preterm infants is deemed an essential requirement for hospital discharge. Despite achieving discharge readiness, feeding problems persist into childhood and can have a residual impact into adulthood. The early diagnosis and management of feeding problems are essential requisites to mitigate any potential long-term challenges in preterm-born adults.

- prematurity

- dysphagia

- oral feeding

- deglutition

1. Introduction

Oral feeding readiness in preterm infants is a concern often towards the tail-end of hospitalization. This only comes into the spotlight after other major medical concerns have been resolved or are manageable. While the evidence for the adult outcomes of preterm infants is increasing, the long-term impact of the altered development of oral neuromotor skills and abnormal oral feeding remains unclear, primarily due to a paucity of studies on adults born preterm. Given the diversity of underlying etiologies and clinical presentations of feeding problems, the lack of standardized definitions and assessments by which to identify and document oral feeding problems adequately is frustrating [1]. There is an urgent need for a two-pronged approach to feeding problems in infants born preterm in order to standardize diagnostic criteria and to develop individualized therapeutic strategies using a comprehensive multidisciplinary approach.

2. Oral Feeding and Feeding Problems in Preterm Infants

2.1. Development of Normal Swallowing in the Fetus

2.2. Feeding Problems in Preterm Infants in the Neonatal Period

3. Feeding Problems in Preterm Infants beyond the NICU

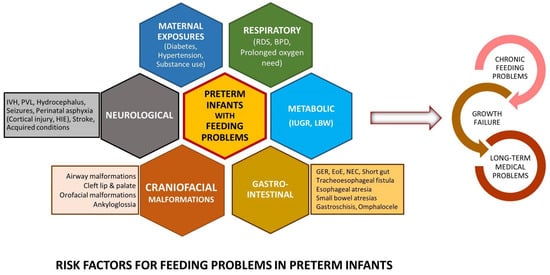

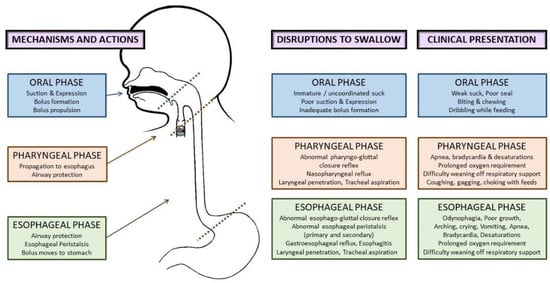

Feeding problems in childhood and adults among preterm born infants have been described inconsistently. While previous studies have suggested that up to 1% of the pediatric population can present with feeding problems, the prevalence is likely to be significantly higher in preterm infants, proportional to the degree of prematurity [7]. Residual feeding problems in growing preterm infants span a broad spectrum of phenotypes, including feeding tube dependency [12], non-specific feeding difficulties, oral aversion [1][13][14], feeding aversion, poor progression to solid foods, challenges with eating specific food types (e.g., solids), and subtle swallowing difficulties.

Outcomes in Preterm Infants with Potential Link to Feeding Problems

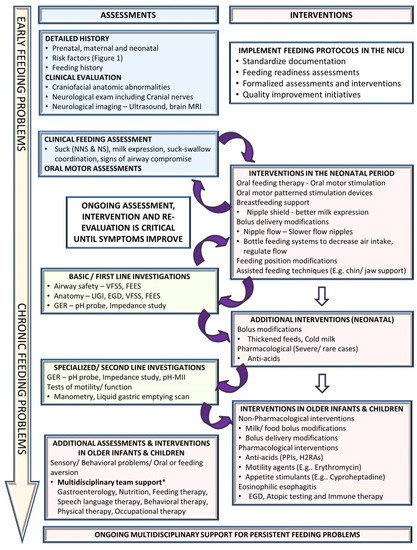

4. Addressing Oral Feeding Issues Early

4.1. Clinical Assessment

4.2. Non-Pharmacological Interventions

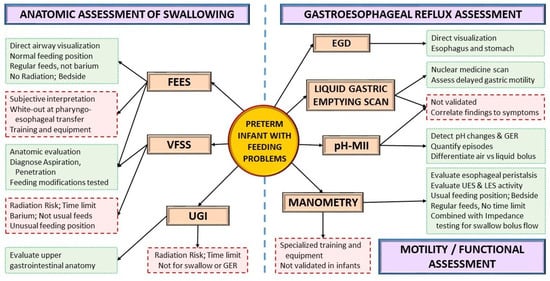

4.3. Instrumental Assessment

4.4. Pharmacological Interventions

5. Future Directions

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/children8121158

References

- Pados, B.F.; Hill, R.R.; Yamasaki, J.T.; Litt, J.S.; Lee, C.S. Prevalence of problematic feeding in young children born prematurely: A meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2021, 21, 110.

- Viswanathan, S.; Jadcherla, S. Feeding and Swallowing Difficulties in Neonates: Developmental Physiology and Patho-physiology. Clin. Perinatol. 2020, 47, 223–241.

- Lau, C.; Schanler, R.J. Oral Motor Function in the Neonate. Clin. Perinatol. 1996, 23, 161–178.

- Wolff, P.H. The serial organization of sucking in the young infant. Pediatrics 1968, 42, 943–956.

- Barlow, S.M.; Poore, M.A.; Zimmerman, E.A.; Finan, D.S. Feeding Skills in the Preterm Infant. ASHA Lead. 2010, 15, 22–23.

- Gewolb, I.H.; Vice, F.L.; Schweitzer-Kenney, E.L.; Taciak, V.L.; Bosma, J.F. Developmental patterns of rhythmic suck and swallow in preterm infants. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2001, 43, 22–27.

- Dodrill, P.; Gosa, M.M. Pediatric Dysphagia: Physiology, Assessment, and Management. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 66, 24–31.

- Jadcherla, S. Dysphagia in the high-risk infant: Potential factors and mechanisms1–3. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 622S–628S.

- Barlow, S.M.; Finan, D.S.; Lee, J.; Chu, S. Synthetic orocutaneous stimulation entrains preterm infants with feeding difficulties to suck. J. Perinatol. 2008, 28, 541–548.

- Barlow, S.M. Central pattern generation involved in oral and respiratory control for feeding in the term infant. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2009, 17, 187–193.

- Azuma, D.; Maron, J.L. Individualizing Oral Feeding Assessment and Therapies in the Newborn. Res. Rep. Neonatol. 2020, 10, 23–30.

- Jadcherla, S.R.; Khot, T.; Moore, R.; Malkar, M.; Gulati, I.K.; Slaughter, J. Feeding Methods at Discharge Predict Long-Term Feeding and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Preterm Infants Referred for Gastrostomy Evaluation. J. Pediatr. 2017, 181, 125–130.e1.

- Pagliaro, C.L.; Bühler, K.E.B.; Ibidi, S.M.; Limongi, S.C.O. Dietary transition difficulties in preterm infants: Critical literature review. J. Pediatr. 2016, 92, 7–14.

- Johnson, S.; Matthews, R.; Draper, E.S.; Field, D.J.; Manktelow, B.N.; Marlow, N.; Smith, L.K.; Boyle, E.M. Eating difficulties in children born late and moderately preterm at 2 y of age: A prospective population-based cohort study1–3. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 406–414.

- Cosmi, E.; Fanelli, T.; Visentin, S.; Trevisanuto, D.; Zanardo, V. Consequences in Infants That Were Intrauterine Growth Restricted. J. Pregnancy 2011, 2011, 364381.

- Eryigit-Madzwamuse, S.; Wolke, D. Attention problems in relation to gestational age at birth and smallness for gestational age. Early Hum. Dev. 2015, 91, 131–138.

- Lewandowski, A.J.; Bradlow, W.M.; Augustine, D.; Davis, E.F.; Francis, J.; Singhal, A.; Lucas, A.; Neubauer, S.; McCormick, K.; Leeson, P. Right Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction in Young Adults Born Preterm. Circulation 2013, 128, 713–720.

- Medoff-Cooper, B.; Irving, S.Y.; Hanlon, A.L.; Golfenshtein, N.; Radcliffe, J.; Stallings, V.A.; Marino, B.S.; Ravishankar, C. The Association among Feeding Mode, Growth, and Developmental Outcomes in Infants with Complex Congenital Heart Disease at 6 and 12 Months of Age. J. Pediatr. 2016, 169, 154–159.e1.

- Park, J.; Pados, B.; Thoyre, S.M. Systematic Review: What Is the Evidence for the Side-Lying Position for Feeding Preterm Infants? Adv. Neonatal Care 2018, 18, 285–294.

- Pados, B.F. Milk Flow Rates from Bottle Nipples: What We Know and Why It Matters. Nurs. Women’s Health 2021, 25, 229–235.

- Arvedson, J.C. Assessment of pediatric dysphagia and feeding disorders: Clinical and instrumental approaches. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2008, 14, 118–127.

- Arvedson, J.C.; Lefton-Greif, M.A. Instrumental Assessment of Pediatric Dysphagia. Semin. Speech Lang. 2017, 38, 135–146.

- Schatz, K.; Langmore, S.; Olson, N. Endoscopic and Videofluoroscopic Evaluations of Swallowing and Aspiration. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1991, 100, 678–681.

- Suterwala, M.S.; Reynolds, J.; Carroll, S.; Sturdivant, C.; Armstrong, E.S. Using fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing to detect laryngeal penetration and aspiration in infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. J. Perinatol. 2017, 37, 404–408.

- Reynolds, J.; Carroll, S.; Sturdivant, C. Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing: A Multidisciplinary Alternative for Assessment of Infants with Dysphagia in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Adv. Neonatal Care 2016, 16, 37–43.

- Armstrong, E.S.; Reynolds, J.; Carroll, S.; Sturdivant, C.; Suterwala, M.S. Comparing videofluoroscopy and endoscopy to assess swallowing in bottle-fed young infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. J. Perinatol. 2019, 39, 1249–1256.

- Kamity, R.; Ferrara, L.; Dumpa, V.; Reynolds, J.; Islam, S.; Hanna, N. Simultaneous Videofluoroscopy and Endoscopy for Dysphagia Evaluation in Preterm Infants—A Pilot Study. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 573.

- Miller, C.K.; Willging, J.P. Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing in Infants and Children: Protocol, Safety, and Clinical Efficacy: 25 Years of Experience. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2020, 129, 469–481.

- Vetter-Laracy, S.; Osona, B.; Roca, A.; Peña-Zarza, J.A.; Gil, J.A.; Figuerola, J. Neonatal swallowing assessment using fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES). Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2018, 53, 437–442.

- Eichenwald, E.C. Committee on Fetus and Newborn Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux in Preterm Infants. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20181061.

- Jadcherla, S.R.; Berseth, C.L. Effect of Erythromycin on Gastroduodenal Contractile Activity in Developing Neonates. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2002, 34, 16–22.

- Ng, E.; Shah, V.S. Erythromycin for the prevention and treatment of feeding intolerance in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, 3, CD001815.

- Basu, S.; Smith, S. Macrolides for the prevention and treatment of feeding intolerance in preterm low birth weight infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 180, 353–378.

- Cooper, W.O.; Griffin, M.R.; Arbogast, P.; Hickson, G.B.; Gautam, S.; Ray, W.A. Very Early Exposure to Erythromycin and Infantile Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2002, 156, 647–650.

- Lavenstein, A.F.; Dacaney, E.P.; Lasagna, L.; Vanmetre, T.E. Effect of Cyproheptadine on Asthmatic Children. JAMA 1962, 180, 912–916.

- Harrison, M.; Norris, M.L.; Robinson, A.; Spettigue, W.; Morrissey, M.; Isserlin, L. Use of cyproheptadine to stimulate appetite and body weight gain: A systematic review. Appetite 2019, 137, 62–72.

- Bapat, R.; Gulati, I.K.; Jadcherla, S. Impact of SIMPLE Feeding Quality Improvement Strategies on Aerodigestive Milestones and Feeding Outcomes in BPD Infants. Hosp. Pediatr. 2019, 9, 859–866.

- Behrman, R.E.; Butler, A.S. (Eds.) Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2007. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes. 12, Societal Costs of Preterm Birth. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11358/ (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Martin, J.A.; Osterman, M.J.K. Describing the Increase in Preterm Births in the United States, 2014–2016; NCHS Data Brief, No 312; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2018.