Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Allergy

Central nervous system (CNS) metastases can occur in a high percentage of systemic cancer patients and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in these patients. Almost any histology can find its way to the brain, but lung, breast, and melanoma are the most common pathologies seen in the CNS from metastatic disease.

- intraparenchymal metastases

- CNS disease

- metastatic disease

- targeted therapy

1. Introduction

Metastatic cancer can often find its way to the brain, where deposits may form either in the brain parenchyma itself resulting in intracranial or intraparenchymal metastases (IPM) or colonize the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) surrounding the brain and spinal cord, resulting in leptomeningeal disease (LMD). Central nervous system (CNS) spread of systemic cancer as IPM or LMD is estimated to occur in 5–40% of patients with metastatic cancer; however, the actual prevalence may be even higher given CNS spread is not always identified before death and not routinely reported to state cancer registries [1][2]. Lung, breast, and melanoma are the most common sources of CNS metastases, though any cancer may metastasize to the parenchyma or CSF. IPM result in significant morbidity and negatively impact median overall survival (OS); indeed, patients with IPM are considered to have late or advanced stage cancer with a survival typically estimated to be less than six months [3]. Radiation therapy (RT), either via stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) or whole brain radiation therapy (WBRT), remain the primary modalities of treatment. However, there has been a notable increase in systemic therapy options for patients with IPM over the last decade, which has dramatically improved the landscape in terms of both progression-free survival (PFS) and OS for patients with several of these cancers.

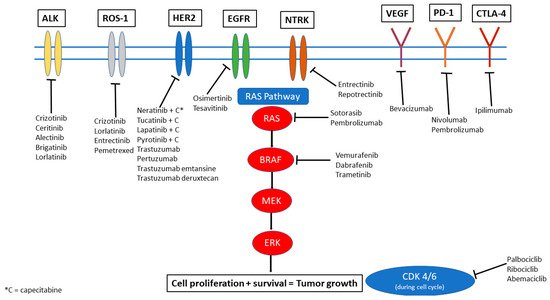

Systemic options that have been more successful in controlling intracranial and extracranial disease are those that specifically target genomic alterations in the tumor. Several actionable genetic alterations have been identified in a range of primary cancers. In this review, we aim to discuss the most common and significant mutations and their respective targeted therapies. Figure 1 provides a visual overview of these targets and highlights the key drugs currently available that can target these mutations to inhibit downstream signaling pathways and also have been noted to have some degree of penetration and efficacy in the CNS. It is important to note, however, that IPM may not always share the same alterations as the extracranial disease. Genetic makeup of the primary cancer is not necessarily always a surrogate for the alterations that may be seen within CNS disease through a phenomenon called “branched evolution,” suggesting the need for sampling directly from the CNS when feasible [4][5].

Figure 1. Therapeutic options illustrated by molecular target.

2. ALK-Targeted Therapies

The anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene translocation is noted in 4–7% of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cases and results in a fusion between ALK and a second gene (most commonly EML4). ALK is a key regulator of tumor cell growth and survival, and this translocation results in increased activation of the signaling pathway, promoting oncogenic cell proliferation and survival. The tyrosine kinase domain of ALK can be targeted by a number of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (Figure 1). Crizotinib was the first of this class of drugs but demonstrated only marginally improved intracranial activity compared to chemotherapy. The newer generations of ALK inhibitors including ceritinib, alectinib, brigatinib, lorlatinib all demonstrated greater blood–brain barrier (BBB) penetration and CNS activity. Phase III trials in NSCLC with ceritinib have demonstrated an improved PFS when compared to chemotherapy (5.4 ms vs. 1.6 ms) [6]. In a phase II trial with pre-treated NSCLC patients, median PFS was 16.6 months and median overall survival (OS) was 51.3 months [7]. Intracranial disease control rate (DCR) was as high as 80% with a median duration of response (DOR) of 24 months [7]. A trial with leptomeningeal disease (LMD) from NSCLC also demonstrated an overall response rate (ORR) of 16.7% with OS of 7.2 months in the LMD group [8].

Alectinib similarly demonstrates CNS activity and PFS benefit in patients regardless of IPM status. When compared to crizotinib, alectinib demonstrates a significantly high PFS (not reached vs. 10.2 months) [9]. In addition, alectinib has been shown to be protective against CNS disease progression based on results from a Phase III study in which only 12% in the alectinib arm had intracranial disease progression versus 45% in the crizotinib arm [10]. Alectinib generally was well tolerated, with primary side effects being anemia, myalgias, weight gain, and photosensitivity. Crizotinib, on the other hand, has a higher rate of nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting [10].

Brigatinib similarly demonstrates a better profile when compared to crizotinib and appears to be well tolerated. In a trial involving patients with NSCLC, median PFS was 29 months with brigatinib versus 9.2 months with crizotinib, with a confirmed rate of intracranial response rate of 78% vs. 29%, respectively [11]. Diarrhea is more common with brigatinib than alectinib, and other side effects included elevated creatine phosphokinase, cough, hypertension, and increased liver function tests [11].

Lorlatinib is a third generation TKI that has been designed to cross the BBB. In a phase III trial comparing lorlatinib to crizotinib that enrolled untreated patients with ALK rearrangements, intracranial response was 66% vs. 20%. As many as 71% of patients were noted to have complete response (CR) intracranially and at 12 months 72% still maintained response suggesting impressive durability to treatment. Similar to alectinib, lorlatinib tends to delay time to CNS progression, with the risk of CNS progression as low as 3% with lorlatinib versus 33% with crizotinib [12]. Lorlatinib is noted to have an added risk of memory impairment and cognitive issues.

Given the robust response data seen even in untreated patients with these later generation TKIs, the question arises if radiation therapy (RT) should be deferred or included for IPM from ALK rearranged NSCLC. No prospective data is available, and retrospective studies still suggest that there is benefit of added RT [13]. In specific clinical scenarios, including patients with small or asymptomatic IPM, IT may be reasonable to defer upfront RT for systemic therapy first.

ALK rearrangements are generally mutually exclusive to the other mutations discussed here with the exception of ROS1, which may co-exist with the ALK translocation and is discussed separately in this review. It is rare now in most countries where these drugs are available to use standard chemotherapy as first-line therapy and for patients with known IPM or relapsed/progressive disease with IPM, we recommend the use of lorlatinib or brigatinib to achieve disease control given the increased CNS penetration and excellent demonstrated efficacy as discussed above. Careful consideration of individual patient tolerance and risk of side effects should also be part of the decision-making process.

3. EGFR Targeted Therapies

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is a member of the ErbB family of receptors. This transmembrane protein has important activity that can encourage growth factor signaling—over-expression or activation of the EGFR pathway results in increased cell proliferation and cell survival, via downstream activation of the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K/AKT) and Janus kinase (JAK/STAT) pathways. This mutation has been noted to occur in up to 35% of primary NSCLC patients, with a higher rate in those with an Asian ethnicity. The third-generation drug osimertinib is especially effective as a TKI for EGFR especially given it can also target the T790M mutation, an escape mutation on exon 20 that has been seen to confer resistance to TKI therapy. Osimertinib has demonstrated efficacy in treating EGFR-mutant NSCLC with CNS extension when compared to chemotherapy (platinum/pemetrexed) and to previous generation TKIs (gefitinib or erlotinib), a situation which prior to this would have had few therapeutic options. In the AURA 3 trial, osimertinib was compared to the previous standard chemotherapy (a combination of platinum/pemetrexed), and the CNS overall response rate was 70% vs. 31%. Median CNS response duration was noted to be 8.9 months [14]. When osimertinib was compared to gefitinib or erlotinib in the FLAURA trial, osimertinib demonstrated a CNS objective response rate of 91% and a median PFS that was not reached vs. 13.9 months in the control arm [15]. New CNS lesions only occurred in 12% of the osimertinib arm vs. 30% of the control arm, also suggesting a protective effect, with an overall median OS of 39 months vs. 32 months [15][16]. For LMD, a phase II prospective study found an impressive intracranial response rate of 55% and a median OS of 16.9 months for NSCLC with LMD. Osimertinib is generally well tolerated, with the most common side effects being diarrhea, dry skin, rash, and mucositis.

Osimertinib monotherapy is therefore becoming the standard first line therapy for EGFR mutated lung cancer. Inclusion of RT, specifically SRS, is also being questioned. While SRS may help with drug penetration or sensitize existing IPM, there is no clear randomized data to support this currently. Previous retrospective studies looked at this question with previous generation TKIs and found that addition of SRS did appear to improve survival [17]. Osimertinib is notably superior to these previous generations, however, in terms of IC response rate, and retrospective data demonstrates that RT may not add much benefit [18]. An ongoing prospective trial evaluating osimertinib versus osimertinib with SRS aims to better answer this question (NCT03769103, Table 1).

Table 1. Ongoing trials targeting IPM with targetable mutations.

| Targeted Mutations | Trial | Phase | Population | Investigational Drug(s) | Total n | Primary Outcome | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALK, ROS1 | NCT02927340 | II | NSCLC | Loratinib | 30 | Intracranial disease control rate | |

| ALK, ROS1 | NCT01970865 | I/II | NSCLC | PF-06463922 vs. Crizotinib monotherapy | 334 | Participants with DLT, percentage of participants with overall and intracranial ORR | PF-0643922—ALK/ROS1 inhibitor |

| ALK, ROS1, or NTRK1-3 | NCT03093116 | I/II | Any IPM | Repotrectinib | 450 | DLT, recommended Phase II dose, ORR | Multiple arms comparing prior TKI and/or chemotherapy and treatment naïve |

| ALK, ROS1, NTRK1-3 | NCT05004116 | I/II | Any IPM | Repotrectinib + Irinotecan + Temozolomide | 50 | Incidence of DLT, MTD | |

| EGFR | NCT03769103 | II | NSCLC | SRS + Osimertinib vs. Osimertinib monotherapy | 76 | Intracranial PFS | Treatment naïve brain mets included |

| ROS1 | NCT04621188 | II | NSCLC | Loratinib | 84 | ORR | Recurrence after failure of first-line TKI |

| ROS1 | NCT03612154 | II | NSCLC | Loratinib | 35 | ORR | |

| ROS1 | NCT04919811 | II | NSCLC or other IPM | Taletrectinib (DS-6051b) | 119 | ORR | |

| ROS1, NTRK | NCT02675491 | I | Any IPM | DS-6051b | 15 | Number and severity of adverse events | |

| CDK, PI3K, NTRK/ROS1 | NCT03994796 | II | Any IPM | Abemaciclib or Paxalisib or Entrectinib | 150 | ORR | CDK population—Ademaciclib, PI3K—Paxalisib, NTRK/ROS1—Entrectinib |

| KRAS, EGFR | NCT01859026 | I/IB | NSCLC | Erlotinib + MEK162 | 43 | MTD | |

| KRAS | NCT03299088 | I | NSCLC | Pembrolizumab + Trametinib | 15 | Incidence of DLT | |

| KRAS | NCT03170206 | I/II | NSCLC | Palbociclib or Binimetinib monotherapy vs. combination therapy | 72 | MTD, safety and tolerability, PFS | CDK4/6 inhibitor + MEK inhibitor |

| KRAS | NCT03808558 | II | NSCLC | TVB-2640 | 12 | Disease control rate and response rate | |

| KRAS | NCT04111458 | I | Any IPM | BI-1701963 monotherapy vs. co-administration with Trametinib | 80 | MTD based on DLT, number of patients with DLT, ORR | |

| KRASG12C | NCT03785249 | I/II | Any IPM | MRTX849 (Adagrasib) monotherapy vs. combination therapy with Pembrolizumab, Cetuximab, or Afatinib | 565 | Safety, pharmacokinetics, and clinical activity/efficacy of MRTX849 | |

| CDK | NCT02896335 | II | Any IPM | Palbociclib | 30 | Clinical benefit rate (intracranial) | |

| HER-2 negative | NCT04647916 | II | Breast cancer | Sacituzumab Govitecan | 44 | ORR | |

| BRAFV600 | NCT03911869 | II | Melanoma | Encorafebib + Binimetinib vs. high dose | 13 | Incidence of DLT, incidence and severity of AE, incidence of dose modifications and discontinuations due to AE, brain metastasis response rate | |

| Checkpoint inhibition | NCT03340129 | II | Melanoma | Ipilimumab + nivolumab w/ RT vs. Ipilimumab + Nivolumab alone | 218 | Neurological specific cause of death |

AE: adverse effects, DLT: dose-limiting toxicity, IPM: intraparenchymal metastases, MTD: maximum tolerated dose, NSLC: non-small cell lung cancer, ORR: overall response rate, PFS: progression free survival, TKI: tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

On the horizon is tesevatinib, a novel TKI with selectivity towards both EGFR and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) that has demonstrated promising CNS penetration [19]. A phase II clinical trial in NSCLC brain metastases is evaluating this drug (NCT02616393, Table 1).

EGFR mutations are noted in other solid cancers such as colon cancer, esophageal cancer, glioblastoma, etc. However, at this time, studies utilizing EGFR TKIs in these other pathologies have not demonstrated the same level of efficacy or success in arresting tumor growth (especially when it comes to the CNS) as what has been seen in NSCLC. In authors practice, the development of osimertinib has truly changed the landscape for patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC, allowing for a prolonged period of disease remission even with CNS IPM, with relatively tolerable side effects. Osimertinib may also be used in the setting of small and asymptomatic brain metastases where RT is being deferred.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers14010017

References

- Kromer, C.; Xu, J.; Ostrom, Q.; Gittleman, H.; Kruchko, C.; Sawaya, R.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. Estimating the annual frequency of synchronous brain metastasis in the United States 2010–2013: A population-based study. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2017, 134, 55–64.

- Schouten, L.J.; Rutten, J.; Huveneers, H.A.M.; Twijnstra, A. Incidence of brain metastases in a cohort of patients with carcinoma of the breast, colon, kidney, and lung and melanoma. Cancer 2002, 94, 2698–2705.

- Villano, J.L.; Durbin, E.B.; Normandeau, C.; Thakkar, J.P.; Moirangthem, V.; Davis, F.G. Incidence of brain metastasis at initial presentation of lung cancer. Neuro Oncol. 2014, 17, 122–128.

- Brastianos, P.K.; Carter, S.L.; Santagata, S.; Cahill, D.; Taylor-Weiner, A.; Jones, R.T.; Van Allen, E.M.; Lawrence, M.S.; Horowitz, P.; Cibulskis, K.; et al. Genomic Characterization of Brain Metastases Reveals Branched Evolution and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Cancer Discov. 2015, 5, 1164–1177.

- Wang, H.; Ou, Q.; Li, D.; Qin, T.; Bao, H.; Hou, X.; Wang, K.; Wang, F.; Deng, Q.; Liang, J.; et al. Genes associated with increased brain metastasis risk in non–small cell lung cancer: Comprehensive genomic profiling of 61 resected brain metastases versus primary non–small cell lung cancer (Guangdong Association Study of Thoracic Oncology 1036). Cancer 2019, 125, 3535–3544.

- Shaw, A.T.; Kim, T.M.; Crinò, L.; Gridelli, C.; Kiura, K.; Liu, G.; Novello, S.; Bearz, A.; Gautschi, O.; Mok, T.; et al. Ceritinib versus chemotherapy in patients with ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer previously given chemotherapy and crizotinib (ASCEND-5): A randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 874–886.

- Nishio, M.; Felip, E.; Orlov, S.; Park, K.; Yu, C.-J.; Tsai, C.-M.; Cobo, M.; McKeage, M.; Su, W.-C.; Mok, T.; et al. Final Overall Survival and Other Efficacy and Safety Results From ASCEND-3: Phase II Study of Ceritinib in ALKi-Naive Patients With ALK-Rearranged NSCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2019, 15, 609–617.

- Chow, L.; Barlesi, F.; Bertino, E.; Bent, M.V.D.; Wakelee, H.; Wen, P.; Chiu, C.-H.; Orlov, S.; Majem, M.; Chiari, R.; et al. Results of the ASCEND-7 phase II study evaluating ALK inhibitor (ALKi) ceritinib in patients (pts) with ALK+ non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) metastatic to the brain. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, v602–v603.

- Hida, T.; Nokihara, H.; Kondo, M.; Kim, Y.H.; Azuma, K.; Seto, T.; Takiguchi, Y.; Nishio, M.; Yoshioka, H.; Imamura, F.; et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in patients with ALK -positive non-small-cell lung cancer (J-ALEX): An open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 29–39.

- Peters, S.; Camidge, D.R.; Shaw, A.T.; Gadgeel, S.; Ahn, J.S.; Kim, D.W.; Ou, S.-H.I.; Pérol, M.; Dziadziuszko, R.; Rosell, R.; et al. Alectinib versus Crizotinib in Untreated ALK-Positive Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 829–838.

- Camidge, D.R.; Kim, H.R.; Ahn, M.-J.; Yang, J.C.H.; Han, J.-Y.; Hochmair, M.J.; Lee, K.H.; Delmonte, A.; Campelo, M.R.G.; Kim, D.-W.; et al. Brigatinib Versus Crizotinib in Advanced ALK Inhibitor–Naive ALK-Positive Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer: Second Interim Analysis of the Phase III ALTA-1L Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38.

- Shaw, A.T.; Bauer, T.M.; De Marinis, F.; Felip, E.; Goto, Y.; Liu, G.; Mazieres, J.; Kim, D.-W.; Mok, T.; Polli, A.; et al. First-Line Lorlatinib or Crizotinib in Advanced ALK-Positive Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2018–2029.

- Johung, K.L.; Yeh, N.; Desai, N.B.; Williams, T.M.; Lautenschlaeger, T.; Arvold, N.D.; Ning, M.S.; Attia, A.; Lovly, C.; Goldberg, S.; et al. Extended Survival and Prognostic Factors for Patients With ALK-Rearranged Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer and Brain Metastasis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 123–129.

- Wu, Y.-L.; Ahn, M.-J.; Garassino, M.C.; Han, J.-Y.; Katakami, N.; Kim, H.R.; Hodge, R.; Kaur, P.; Brown, A.P.; Ghiorghiu, D.; et al. CNS Efficacy of Osimertinib in Patients With T790M-Positive Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Data From a Randomized Phase III Trial (AURA3). J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2702–2709.

- Reungwetwattana, T.; Nakagawa, K.; Cho, B.C.; Cobo, M.; Cho, E.K.; Bertolini, A.; Bohnet, S.; Zhou, C.; Lee, K.H.; Nogami, N.; et al. CNS Response to Osimertinib Versus Standard Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Patients With Untreated EGFR-Mutated Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 3290–3297.

- Ramalingam, S.S.; Vansteenkiste, J.; Planchard, D.; Cho, B.C.; Gray, J.E.; Ohe, Y.; Zhou, C.; Reungwetwattana, T.; Cheng, Y.; Chewaskulyong, B.; et al. Overall Survival with Osimertinib in Untreated, EGFR-Mutated Advanced NSCLC. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 41–50.

- Magnuson, W.J.; Lester-Coll, N.; Wu, A.J.; Yang, T.J.; Lockney, N.; Gerber, N.K.; Beal, K.; Amini, A.; Patil, T.; Kavanagh, B.D.; et al. Management of Brain Metastases in Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor–Naïve Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor–Mutant Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Retrospective Multi-Institutional Analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 1070–1077.

- Xie, L.; Nagpal, S.; Wakelee, H.A.; Li, G.; Soltys, S.G.; Neal, J.W. Osimertinib for EGFR -Mutant Lung Cancer with Brain Metastases: Results from a Single-Center Retrospective Study. Oncologist 2018, 24, 836–843.

- Lin, N.U.; Freedman, R.A.; Miller, K.; Jhaveri, K.L.; Eiznhamer, D.A.; Berger, M.S.; Hamilton, E.P. Determination of the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of the CNS penetrant tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) tesevatinib administered in combination with trastuzumab in HER2+ patients with metastatic breast cancer (BC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 514.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!