Treatment strategies targeting programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) or its ligand, PD-L1, have been developed as immunotherapy against tumor progression for various cancer types including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The recent pivotal clinical trials of immune-checkpoint inhibiters (ICIs) combined with cytotoxic chemotherapy have reshaped therapeutic strategies and established various first-line standard treatments. The therapeutic effects of ICIs in these clinical trials were analyzed according to PD-L1 tumor proportion scores or tumor mutational burden; however, these indicators are insufficient to predict the clinical outcome. Consequently, molecular biological approaches including multiomics analyses have addressed other mechanisms of cancer immune escape and have revealed an association of NSCLC containing specific driver mutations with distinct immune phenotypes. NSCLC has been characterized by driver mutation-defined molecular subsets and the effect of driver mutations on the regulatory mechanism of PD-L1 expression on the tumor itself.

- immune-checkpoint blockade

- PD-1

- PD-L1

- NSCLC

- driver mutation

1. Introduction

2. Current ICI Therapeutic Strategies in NSCLC

2.1. Mono Therapy with PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors

| Clinical Study | Patient | Experimental Arm | Control Arm | PFS | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KEYNOTE-024 | NSCLC, PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50% |

Pembrolizumab | Platinum-based chemotherapy | HR 0.50 (95% CI, 0.37–0.68) |

HR 0.60 (95% CI, 0.41–0.89) |

| KEYNOTE-042 | NSCLC, PD-L1 TPS ≥ 1% |

Pembrolizumab | Platinum-based chemotherapy | HR 1.07 (95% CI, 0.94–1.21) |

HR 0.81 (95% CI, 0.71–0.93) |

| IMpower110 | NSCLC, PD-L1 TC3 or IC3 |

Atezolizumab | Platinum-based chemotherapy | HR 0.63 (95% CI, 0.45–0.88) |

HR 0.59 (95% CI, 0.40–0.89) |

| KEYNOTE-189 | Non-Sq NSCLC | Pembrolizumab + CDDP/CBDCA + PEM | CDDP/CBDCA+PEM | HR 0.52 (95% CI, 0.43–0.64) |

HR 0.49 (95% CI, 0.38–0.64) |

| KEYNOTE-407 | Sq NSCLC | Pembrolizumab + CBDCA + nabPTX/PTX | CBDCA+nabPTX/PTX | HR 0.56 (95% CI, 0.45–0.70) |

HR 0.64 (95% CI, 0.49–0.85) |

| IMpower130 | Non-Sq NSCLC | Atezolizumab + CBDCA + nabPTX | CBDCA+nabPTX | HR 0.64 (95% CI, 0.54–0.77) |

HR 0.79 (95% CI, 0.64–0.98) |

| IMpower132 | Non-Sq NSCLC | Atezolizumab + CDDP/CBDCA + PEM | CDDP/CBDCA+PEM | HR 0.60 (95% CI, 0.49–0.72) |

HR 0.86 (95% CI, 0.71–1.06) |

| IMpower150 | Non-Sq NSCLC | Atezolizumab + CBDCA + PTX + BEV | CBDCA+PTX+BEV | HR 0.62 (95% CI, 0.52–0.74) |

HR 0.78 (95% CI, 0.64–0.96) |

| ONO-4538–52/TASUKI-52 | Non-Sq NSCLC | Nivolumab + CBDCA+PTX + BEV | CBDCA+PTX+BEV | HR 0.56 (95% CI, 0.43–0.71) |

HR 0.85 (95% CI, 0.63–1.14) |

| POSEIDON | NSCLC | Durvalumab + Platinum-based chemotherapy | Platinum-based chemotherapy | HR 0.74 (95% CI, 0.62–0.89) |

HR 0.86 (95% CI, 0.72–1.02) |

| CheckMate 227 | NSCLC PD-L1 level ≥ 1% |

Nivolumab + Ipilimumab | Platinum-based chemotherapy | HR 0.82 (95%CI, 0.69–0.97) |

HR 0.79 (97.72% CI, 0.65–0.96) |

| CheckMate 9LA | NSCLC | Nivolumab + Ipilimumab + Platinum based chemotherapy | Platinum-based chemotherapy | HR 0.70 (97.48%CI, 0.57–0.86) |

HR 0.69 (96.71% CI, 0.55–0.87) |

| POSEIDON | NSCLC | Durvalumab + Tremelimumab + Platinum-based chemotherapy | Platinum-based chemotherapy | HR 0.72 (95% CI, 0.60–0.86) |

HR 0.77 (95% CI, 0.65–0.92) |

2.2. PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors in Combination with Platinum-Based Chemotherapy

2.3. PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors in Combination with Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte-Associated Protein 4 (CTLA-4) Inhibitors

2.4. PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors Plus CTLA-4 Inhibitors in Combination with Platinum-Based Chemotherapy

3. PD-L1 Upregulation Mechanisms in NSCLC with KRAS Mutation

3.1. Heterogeneity of PD-L1 expression and ICIs efficacy in NSCLC with KRAS mutation

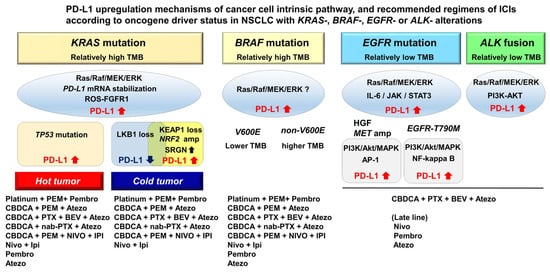

Positive PD-L1 staining was more frequent in patients with KRAS mutation compared with wild-type KRAS patients in the KEYNOTE-001 study [56]. Consistently, monotherapy with anti-PD-1 antibodies, such as nivolumab or pembrolizumab, initially showed a greater clinical benefit in patients with KRAS mutation compared with KRAS wild-type patients [56]. However, a multiomics analysis uncovered the heterogeneity of KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinomas based on cooccurring genetic alterations including inactivation of TP53 or LKB1 and low expression of the thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) [23, 24]. The integrative analysis with clinical data indicated that these distinct subsets affect PD-L1 expression and the response to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (Figure 1). Among them, KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinomas with TP53 inactivation is characterized as high PD-L1 expression together with high TMB and marked T-cell infiltration, and showing favorable responses to monotherapy with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies [23, 24].

In contrast to TP53 inactivation, lung adenocarcinomas with LKB1 inactivation, which is encoded by serine/threonine kinase 11, is associated with downregulation of PD-L1 expression and reduced T-cell infiltration. Somatic mutation of LKB1 occurs in approximately 20% of lung adenocarcinomas and 30% of KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinomas, whereas LKB1 inactivation is present as a germline mutation of the autosomal dominant disorder, Peutz–Jeghers syndrome [23, 24, 57]. The loss of LKB1 function affects tumor initiation though the dysregulation of cell polarity and the reprograming of energy metabolism, including glucose uptake and pyrimidine/purine balance [58-61]. These drastic intracellular transformations can affect the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 7 (CXCL7), resulting in the accumulation of immunosuppressive neutrophils and exhausted or suppressed infiltrated T cells [62]. Consistent with these basic molecular analyses, a pan-cancer T-cell–inflamed gene expression profile (GEP) consisting of 18 genes, which represent the T-cell–activated tumor microenvironment (TME), revealed that somatic mutation of LKB1 was one of the most prevalent driver alterations in immunosuppressed phenotypes in NSCLC known as “cold tumor” [19]. In fact, anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy is ineffective in NSCLC with LKB1 inactivation, which exhibits primary resistance to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade with PD-L1 negativity and intermediate or high TMB [63].

The KEAP1 inactivating mutation is associated with the immunosuppressive phenotype and is frequently involved in TTF-1-negative lung adenocarcinoma, which was reported as deficient T-cell infiltration from the analysis of a pan-cancer T-cell–inflamed GEP [64]. KEAP1 is a redox-regulated substrate for the cullin-3 dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, which facilitates the ubiquitination and subsequent proteolysis of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2), a master regulator of detoxification, antioxidant response, and antiinflammatory activity [65]. KEAP1 inactivation results in persistent NRF2 activation; therefore, the tumors are highly resistant to radiotherapy and cytotoxic chemotherapy [65-67]. KEAP1 inactivation is also involved in reprogramming to an immunosuppressive TME through Srglycin (SRGN) secretion, which is a chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan that plays an intricate role in inflammation by regulating several inflammatory mediators [68-70]. SRGN expression is transcriptionally upregulated by NRF2 activation and epigenetically induced through nicotinamide N-methyltransferase-induced perturbation of methionine metabolism in TTF-1–negative lung adenocarcinoma [70]. Cancer cell-derived SRGN upregulates PD-L1 expression on the cancer cell itself and increases the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines including IL-6, interleukin-8 (IL-8), and chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 (CXCL1), indicating that it contributes to reprogramming into an aggressive and immunosuppressed phenotype [70, 71]. Similar to NSCLC with LKB1 inactivation, NSCLC with disruption of the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway is widely known respond poorly to monotherapy with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies. Arbour et al. analyzed cooccurring genetic alterations of 330 patients with KRAS-mutant NSCLC by NGS and found that KEAP1-NRF2 alterations occurred in 27% of the patients which had shorter OS from the initiation of immunotherapy [23]. Furthermore, a subset of NSCLC harbors inactivating mutations of both LKB1 and KEAP1/NRF2 and demonstrate a further aggressive clinical course with strong resistance to ICIs treatment [72]. Papillon-Cavanagh et al. analyzed the clinical efficacy of PD1/PD-L1 inhibitors or platinum-based chemotherapy against NSCLC with the double-mutational status in a real world-setting. Patient outcome for both treatments was worse progression-free survival (PFS) and OS compared with patients harboring only an LKB1 alteration, only KEAP1/NRF2 alterations, or a negative status for both [73]. These results indicate that cooccurring genetic alterations of LKB1 and KEAP1/NRF2 have an additive effect for tumor aggressiveness even with combined ICI regimens containing cytotoxic chemotherapy. To improve the outcome of NSCLC with these aggressive phenotypes, new therapeutic developments are needed.

3.2. Association of PD-L1 expression with EGFR mutation and ALK fusion in NSCLC

As with KRAS-mutant-NSCLC, oncogenic Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK signaling upregulates PD-L1 expression in NSCLC with EGFR mutation and ALK fusion [74, 75]. Chen et al. reported that EGFR activation, such as EGF stimulation, exon19 deletion, and exon21 L858R-mutation, upregulates PD-L1 expression through ERK/Jun phosphorylation, but not phosphorylation of the AKT/S6 pathway [76]. In addition, IL-6/Janus Kinase (JAK)/STAT3 signaling also induces PD-L1 expression in EGFR-mutant NSCLC [77], whereas the PI3K-AKT pathway is involved in PD-L1 upregulation in NSCLC with ALK fusion [75] (Figure 1). Furthermore, several molecular mechanisms of resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs), such as hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), c-MET amplification, and EGFR-T790M mutation, were associated with upregulation of PD-L1 expression in EGFR-mutant NSCLC. HGF and c-MET amplification increase PD-L1 expression by activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt, mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 (MAPK), and activator protein 1 (AP-1), whereas EGFR-T790M mutation increases PD-L1 expression through NF-kappa B signaling pathways in addition to signaling through PI3K/Akt/MAPK [78]. These results indicate the types of resistance mechanisms to EGFR-TKIs that promote the immune escape of tumor cells through different molecular mechanisms (Figure 1). Based on these findings, several studies showed that PD-L1 expression levels as measured by immunohistochemistry (IHC) are relatively higher in advanced NSCLC with EGFR mutation or ALK fusion compared with that of NSCLC with wild-type EGFR and ALK, though the results of some studies were inconsistent [79-81].

The previous studies indicate that NSCLC with EGFR mutation or ALK fusion does not respond well to PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy compared with EGFR- and ALK-wild-type NSCLC [25, 27, 28, 82]. These results are consistent with the findings of a lack of T-cell infiltration and low TMB in NSCLC with EGFR mutation or ALK fusion [82, 83]. A pool analysis of 4 randomized control trials including ChckMate-057, KEYNOTE-010, OAK and POPLAR showed that the PFS of the patients with EGFR mutation treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors was shorter compared with those of the patients treated with docetaxel (HR, 1.44, 95% CI [1.05–1.98]; P = 0.02) [83]. ATLANTIC, an open-label phase 2 study, demonstrated the potential efficacy of an anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody, durvalumab, for third-line or later-line treatment of advanced NSCLC with EGFR mutation or ALK fusion [84]. In the present study, PD-L1 expression in the tumor was associated with PFS and objective response, indicating that ICIs should not be thoroughly excluded from candidate therapeutic strategies for NSCLC patients with EGFR mutation or ALK fusion, especially in cases with high PD-L1 expression.

3.3. PD-L1 expression in NSCLC with other oncogenic driver mutations

The clinical efficacy of ICI treatment in NSCLC with B-Raf Proto-Oncogene (BRAF) mutation appears similar to that in unselected NSCLC, indicating that patients with BRAF-mutant NSCLC benefit more from ICI therapy than patients with NSCLC harboring an EGFR mutation or ALK fusion [85]. Zhang et al. reported that there were no significant differences in PD-L1 expression between NSCLC with BRAF mutation and wild-type, whereas BRAF mutation was associated with higher TMB compared with BRAF wild-type [86]. Similarly, PFS in patients with BRAF-mutant NSCLC treated with ICIs was approximately 10 months, which was significantly longer compared with patients harboring an EGFR mutation or ALK fusion [87]. Furthermore, there was no significant correlation between PD-L1 expression and clinical response to ICIs in BRAF-mutant NSCLC [85, 88]. Between NSCLC with BRAF V600E mutation and non-V600E alterations, PFS and overall response rate were not significantly different, although NSCLC with BRAF V600E mutation exhibited lower TMB compared with those harboring non-V600E alterations [85] (Figure 1).

In addition to EGFR mutation, a multiomics analysis has identified that activating mutations in receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) genes, such as c-MET mutation or amplification, FGFR1 amplification, human EGFR 2 (HER2) point mutation, and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) amplification, are associated with primary resistance to ICIs regardless of PD-L1 expression and TMB [21, 89]. The activation of Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK signaling also upregulates PD-L1 expression in NSCLC with activated alterations of RTK genes, although IHC of PD-L1 for these genes alterations was not well studied because of the low frequency. Consistent with the results of the multiomics analysis, V Negrao et al. reported the efficacy of ICIs in NSCLC with these low frequency driver alterations and PFS in patients with NSCLC with RTK genes alterations were relatively shorter at approximately 1.8–3.7 months [87]. In contrast, other driver gene mutations, such as JAK1/2 and AT-rich interactive domain-containing protein 1A (ARID1A) mutations, were reported to be associated with T-cell infiltration and favorable response to ICI treatment with high expression of tumor antigens as well as cooccurring KRAS mutations and TP53 inactivation [21, 90]. These driver mutations may be useful predictive markers for PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor response and may useful for stratifying patients for ICI regimens.

4. Current clinical questions and future perspectives

The clinical development of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor-containing regimens has provided advanced NSCLC patients with treatment options, especially with respect to the expected toxicity profile of each regimen. However, several clinical questions regarding the efficacy of these regimens remain, additional clinical studies are ongoing.

4.1. Is monotherapy with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors the best choice in patients with PD-L1 positive expression?

Currently, monotherapy with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors or immune check point inhibitors in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy may be selected. It is unclear whether the addition of platinum-based chemotherapy to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors is beneficial in patients with strong PD-L1 expression. NSCLC with an ARID1A alteration or with combined KRAS mutation and TP53 inactivation showed good responses to ICIs, even to monotherapy with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors [21, 23, 24, 90]. To address this question, a phase III study comparing CBDCA/PEM/pembrolizumab to pembrolizumab in patients with a PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50% is ongoing [91].

4.2. Are PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors or PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors plus CTLA-4 inhibitors a better combination with platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with NSCLC?

As mentioned earlier, quadruple regimens containing PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors plus CTLA-4 inhibitors have become a standard treatment option, which leads us to another clinical question: Are quadruple regimens better than triplet regimen with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors combined with platinum-based chemotherapy? POSEIDON was a three-arm study consisting of durvalumab plus tremelimumab combined with platinum-based chemotherapy versus durvalumab combined with platinum-based chemotherapy, and platinum-based chemotherapy as the control arm. The median OS of the three regimens was 14.0 months, 13.0 months, and 11.7 months, respectively. However, the study was statistically designed to compare durvalumab plus tremelimumab in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy with the control arm (HR of OS: 0.77) and to compare durvalumab combined with platinum-based chemotherapy with the control arm (HR of OS: 0.86). Thus, direct comparison data between PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor combinations with platinum-based chemotherapy and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors plus CTLA-4 inhibitors in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy are needed.

4.3. Are PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors plus platinum-based chemotherapy or PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors plus CTLA4 inhibitors beneficial in NSCLC patients harboring sensitizing EGFR mutations?

IMpower150 demonstrated the potential benefits of adding PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors to platinum-based chemotherapy in NSCLC patients with a sensitizing EGFR mutation. However, it remains unclear whether such patients benefited from a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor-containing regimen. A phase III study comparing nivolumab plus pemetrexed/platinum or nivolumab/ipilimumab to pemetrexed plus platinum in NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations following failure with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy is ongoing (NCT02864251). Furthermore, an ongoing phase III study comparing atezolizumab plus CBDCA/PEM/BEV to CBDCA/PEM/BEV is designed to include patients with an EGFR mutation or ALK fusion who showed treatment failure with an approved tyrosine kinase inhibitor (JapicCTI-194565) [92]. These studies would resolve the questions of the role of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in NSCLC patients with a sensitizing EGFR mutation.

4.4. Is reiteration of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors effective to a subset of the NSCLC population?

The PACIFIC trial demonstrated clinical efficacy of durvalumab monotherapy for patients with locally advanced and unresectable NSCLC after concurrent platinum-based chemoradiotherapy [93]. However, the clinical benefits of the reiteration of PD-1/PD-L1 regimens for patients with recurrent disease after durvalumab are unknown. Regarding the reiteration of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in advanced NSCLC, there are a few case studies to address the efficacy [94-96]; however, most of these cases included other therapies before, after, and between PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor treatment, thus additional effects of cytotoxic chemotherapy or abscopal effects of radiotherapy may impact the analysis. Furthermore, there is the possibility of severe adverse events caused by reiteration of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor therapy. Therefore, further clinical trials that include patients with recurrent NSCLC after durvalumab are needed.

5. Conclusion

In summary, there are now multiple treatment options that contain PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor regimens for chemotherapy naïve advanced NSCLC patients. The optimal use of these treatment options is one of the most important issues in the area of immunotherapy. Several head-to-head trials to investigate which options are more effective for patients with NSCLC. PD-L1 expression status may be used to stratify patients for these trials, although it is known as a week indicator to predict clinical outcome. In parallel to the development of therapeutic strategies using ICIs, recent molecular approaches have begun to elucidate the relationship between key driver mutations and distinct immune phenotypes in NSCLC. A better understanding of these relationships will help in the selection of responders for ICI therapy and to design future clinical trials for precision medicine. In particular, new therapeutic developments for immune resistant phenotypes, such as NSCLC with LKB1 and/or KEAP1 inactivation, are urgently needed to improve the extremely poor prognosis. Combining clinical trial results with molecular biological findings will drive the selection of suitable ICI therapies for patients based on PD-L1 expression status and key driver mutations.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms23010245

References

- Dong, H.; Zhu, G.; Tamada, K.; Chen, L. B7-H1, a third member of the B7 family, co-stimulates T-cell proliferation and interleukin-10 secretion. Nat. Med. 1999, 5, 1365–1369.

- Freeman, G.J.; Long, A.J.; Iwai, Y.; Bourque, K.; Chernova, T.; Nishimura, H.; Fitz, L.J.; Malenkovich, N.; Okazaki, T.; Byrne, M.C.; et al. Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 192, 1027–1034.

- Havel, J.J.; Chowell, D.; Chan, T.A. The evolving landscape of biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 133–150.

- Baggstrom, M.Q.; Stinchcombe, T.E.; Fried, D.B.; Poole, C.; Hensing, T.A.; Socinski, M.A. Third-generation chemotherapy agents in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2007, 2, 845–853.

- Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Collaborative Group. Chemotherapy and supportive care versus supportive care alone for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, 5, CD007309.

- Gandhi, L.; Rodriguez-Abreu, D.; Gadgeel, S.; Esteban, E.; Felip, E.; De Angelis, F.; Domine, M.; Clingan, P.; Hochmair, M.J.; Powell, S.F.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2078–2092.

- Nishio, M.; Barlesi, F.; West, H.; Ball, S.; Bordoni, R.; Cobo, M.; Longeras, P.D.; Goldschmidt, J., Jr.; Novello, S.; Orlandi, F.; et al. Atezolizumab Plus Chemotherapy for First-Line Treatment of Nonsquamous NSCLC: Results From the Randomized Phase 3 IMpower132 Trial. J. Thorac. Oncol. Off. Publ. Int. Assoc. Study Lung Cancer 2021, 16, 653–664.

- West, H.; McCleod, M.; Hussein, M.; Morabito, A.; Rittmeyer, A.; Conter, H.J.; Kopp, H.G.; Daniel, D.; McCune, S.; Mekhail, T.; et al. Atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone as first-line treatment for metastatic non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower130): A multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 924–937.

- Socinski, M.A.; Jotte, R.M.; Cappuzzo, F.; Orlandi, F.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Nogami, N.; Rodriguez-Abreu, D.; Moro-Sibilot, D.; Thomas, C.A.; Barlesi, F.; et al. Atezolizumab for First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Nonsquamous NSCLC. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2288–2301.

- Sugawara, S.; Lee, J.S.; Kang, J.H.; Kim, H.R.; Inui, N.; Hida, T.; Lee, K.H.; Yoshida, T.; Tanaka, H.; Yang, C.T.; et al. Nivolumab with carboplatin, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab for first-line treatment of advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2021, 32, 1137–1147.

- Reck, M.; Mok, T.S.K.; Nishio, M.; Jotte, R.M.; Cappuzzo, F.; Orlandi, F.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Nogami, N.; Rodriguez-Abreu, D.; Moro-Sibilot, D.; et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and chemotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower150): Key subgroup analyses of patients with EGFR mutations or baseline liver metastases in a randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019, 7, 387–401.

- Boyer, M.; Sendur, M.A.N.; Rodriguez-Abreu, D.; Park, K.; Lee, D.H.; Cicin, I.; Yumuk, P.F.; Orlandi, F.J.; Leal, T.A.; Molinier, O.; et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Ipilimumab or Placebo for Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer with PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score >/= 50%: Randomized, Double-Blind Phase III KEYNOTE-598 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2327–2338.

- Paz-Ares, L.; Ciuleanu, T.E.; Cobo, M.; Schenker, M.; Zurawski, B.; Menezes, J.; Richardet, E.; Bennouna, J.; Felip, E.; Juan-Vidal, O.; et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab combined with two cycles of chemotherapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 9LA): An international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 198–211.

- Yarchoan, M.; Hopkins, A.; Jaffee, E.M. Tumor Mutational Burden and Response Rate to PD-1 Inhibition. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 2500–2501.

- Gavrielatou, N.; Shafi, S.; Gaule, P.; Rimm, D.L. PD-L1 Expression Scoring: Non-Interchangeable, Non-Interpretable, Neither, or Both. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2021, 113, 1613–1614.

- Wang, X.; Ricciuti, B.; Alessi, J.V.; Nguyen, T.; Awad, M.M.; Lin, X.; Johnson, B.E.; Christiani, D.C. Smoking History as a Potential Predictor of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Efficacy in Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2021, 113, 1761–1769.

- Galuppini, F.; Dal Pozzo, C.A.; Deckert, J.; Loupakis, F.; Fassan, M.; Baffa, R. Tumor mutation burden: From comprehensive mutational screening to the clinic. Cancer Cell Int. 2019, 19, 209.

- Bravaccini, S.; Bronte, G.; Ulivi, P. TMB in NSCLC: A Broken Dream? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6536.

- Cristescu, R.; Mogg, R.; Ayers, M.; Albright, A.; Murphy, E.; Yearley, J.; Sher, X.; Liu, X.Q.; Lu, H.; Nebozhyn, M.; et al. Pan-tumor genomic biomarkers for PD-1 checkpoint blockade-based immunotherapy. Science 2018, 362, 6411.

- Gillette, M.A.; Satpathy, S.; Cao, S.; Dhanasekaran, S.M.; Vasaikar, S.V.; Krug, K.; Petralia, F.; Li, Y.; Liang, W.W.; Reva, B.; et al. Proteogenomic Characterization Reveals Therapeutic Vulnerabilities in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cell 2020, 182, 200–225.e35.

- Anagnostou, V.; Niknafs, N.; Marrone, K.; Bruhm, D.C.; White, J.R.; Naidoo, J.; Hummelink, K.; Monkhorst, K.; Lalezari, F.; Lanis, M.; et al. Multimodal genomic features predict outcome of immune checkpoint blockade in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Cancer 2020, 1, 99–111.

- Tanaka, I.; Furukawa, T.; Morise, M. The current issues and future perspective of artificial intelligence for developing new treatment strategy in non-small cell lung cancer: Harmonization of molecular cancer biology and artificial intelligence. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 454.

- Arbour, K.C.; Jordan, E.; Kim, H.R.; Dienstag, J.; Yu, H.A.; Sanchez-Vega, F.; Lito, P.; Berger, M.; Solit, D.B.; Hellmann, M.; et al. Effects of Co-occurring Genomic Alterations on Outcomes in Patients with KRAS-Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 334–340.

- Skoulidis, F.; Heymach, J.V. Co-occurring genomic alterations in non-small-cell lung cancer biology and therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 495–509.

- Borghaei, H.; Paz-Ares, L.; Horn, L.; Spigel, D.R.; Steins, M.; Ready, N.E.; Chow, L.Q.; Vokes, E.E.; Felip, E.; Holgado, E.; et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1627–1639.

- Brahmer, J.; Reckamp, K.L.; Baas, P.; Crino, L.; Eberhardt, W.E.; Poddubskaya, E.; Antonia, S.; Pluzanski, A.; Vokes, E.E.; Holgado, E.; et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Squamous-Cell Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 123–135.

- Rittmeyer, A.; Barlesi, F.; Waterkamp, D.; Park, K.; Ciardiello, F.; von Pawel, J.; Gadgeel, S.M.; Hida, T.; Kowalski, D.M.; Dols, M.C.; et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): A phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 255–265.

- Herbst, R.S.; Baas, P.; Kim, D.W.; Felip, E.; Perez-Gracia, J.L.; Han, J.Y.; Molina, J.; Kim, J.H.; Arvis, C.D.; Ahn, M.J.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 1540–1550.

- Carbone, D.P.; Reck, M.; Paz-Ares, L.; Creelan, B.; Horn, L.; Steins, M.; Felip, E.; van den Heuvel, M.M.; Ciuleanu, T.E.; Badin, F.; et al. First-Line Nivolumab in Stage IV or Recurrent Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2415–2426.

- Reck, M.; Rodriguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; Hui, R.; Csoszi, T.; Fulop, A.; Gottfried, M.; Peled, N.; Tafreshi, A.; Cuffe, S.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1823–1833.

- Mok, T.S.K.; Wu, Y.L.; Kudaba, I.; Kowalski, D.M.; Cho, B.C.; Turna, H.Z.; Castro, G., Jr.; Srimuninnimit, V.; Laktionov, K.K.; Bondarenko, I.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): A randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 1819–1830.

- Herbst, R.S.; Giaccone, G.; de Marinis, F.; Reinmuth, N.; Vergnenegre, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Morise, M.; Felip, E.; Andric, Z.; Geater, S.; et al. Atezolizumab for First-Line Treatment of PD-L1-Selected Patients with NSCLC. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1328–1339.

- Paz-Ares, L.; Luft, A.; Vicente, D.; Tafreshi, A.; Gumus, M.; Mazieres, J.; Hermes, B.; Cay Senler, F.; Csoszi, T.; Fulop, A.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy for Squamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2040–2051.

- Tanaka, I.; Morise, M.; Miyazawa, A.; Kodama, Y.; Tamiya, Y.; Gen, S.; Matsui, A.; Hase, T.; Hashimoto, N.; Sato, M.; et al. Potential Benefits of Bevacizumab Combined with Platinum-Based Chemotherapy in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients with EGFR Mutation. Clin. Lung Cancer 2020, 21, 273–280.e4.

- Brunet, J.F.; Denizot, F.; Luciani, M.F.; Roux-Dosseto, M.; Suzan, M.; Mattei, M.G.; Golstein, P. A new member of the immunoglobulin superfamily--CTLA-4. Nature 1987, 328, 267–270.

- Dariavach, P.; Mattei, M.G.; Golstein, P.; Lefranc, M.P. Human Ig superfamily CTLA-4 gene: Chromosomal localization and identity of protein sequence between murine and human CTLA-4 cytoplasmic domains. Eur. J. Immunol. 1988, 18, 1901–1905.

- Linsley, P.S.; Brady, W.; Urnes, M.; Grosmaire, L.S.; Damle, N.K.; Ledbetter, J.A. CTLA-4 is a second receptor for the B cell activation antigen B7. J. Exp. Med. 1991, 174, 561–569.

- Linsley, P.S.; Greene, J.L.; Brady, W.; Bajorath, J.; Ledbetter, J.A.; Peach, R. Human B7-1 (CD80) and B7-2 (CD86) bind with similar avidities but distinct kinetics to CD28 and CTLA-4 receptors. Immunity 1994, 1, 793–801.

- Pentcheva-Hoang, T.; Egen, J.G.; Wojnoonski, K.; Allison, J.P. B7-1 and B7-2 selectively recruit CTLA-4 and CD28 to the immunological synapse. Immunity 2004, 21, 401–413.

- Hodi, F.S.; Mihm, M.C.; Soiffer, R.J.; Haluska, F.G.; Butler, M.; Seiden, M.V.; Davis, T.; Henry-Spires, R.; MacRae, S.; Willman, A.; et al. Biologic activity of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 antibody blockade in previously vaccinated metastatic melanoma and ovarian carcinoma patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 4712–4717.

- Hodi, F.S.; O’Day, S.J.; McDermott, D.F.; Weber, R.W.; Sosman, J.A.; Haanen, J.B.; Gonzalez, R.; Robert, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Hassel, J.C.; et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 711–723.

- Schadendorf, D.; Hodi, F.S.; Robert, C.; Weber, J.S.; Margolin, K.; Hamid, O.; Patt, D.; Chen, T.T.; Berman, D.M.; Wolchok, J.D. Pooled Analysis of Long-Term Survival Data From Phase II and Phase III Trials of Ipilimumab in Unresectable or Metastatic Melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1889–1894.

- Hui, E.; Cheung, J.; Zhu, J.; Su, X.; Taylor, M.J.; Wallweber, H.A.; Sasmal, D.K.; Huang, J.; Kim, J.M.; Mellman, I.; et al. T cell costimulatory receptor CD28 is a primary target for PD-1-mediated inhibition. Science 2017, 355, 1428–1433.

- Wei, S.C.; Levine, J.H.; Cogdill, A.P.; Zhao, Y.; Anang, N.A.S.; Andrews, M.C.; Sharma, P.; Wang, J.; Wargo, J.A.; Pe’er, D.; et al. Distinct Cellular Mechanisms Underlie Anti-CTLA-4 and Anti-PD-1 Checkpoint Blockade. Cell 2017, 170, 1120–1133.e17.

- Hellmann, M.D.; Ciuleanu, T.E.; Pluzanski, A.; Lee, J.S.; Otterson, G.A.; Audigier-Valette, C.; Minenza, E.; Linardou, H.; Burgers, S.; Salman, P.; et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Lung Cancer with a High Tumor Mutational Burden. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2093–2104.

- Hellmann, M.D.; Paz-Ares, L.; Bernabe Caro, R.; Zurawski, B.; Kim, S.W.; Carcereny Costa, E.; Park, K.; Alexandru, A.; Lupinacci, L.; de la Mora Jimenez, E.; et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2020–2031.

- Hiam-Galvez, K.J.; Allen, B.M.; Spitzer, M.H. Systemic immunity in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2021, 21, 345–359.

- Lee, S.J.; Jang, B.C.; Lee, S.W.; Yang, Y.I.; Suh, S.I.; Park, Y.M.; Oh, S.; Shin, J.G.; Yao, S.; Chen, L.; et al. Interferon regulatory factor-1 is prerequisite to the constitutive expression and IFN-gamma-induced upregulation of B7-H1 (CD274). FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 755–762.

- Miyazawa, A.; Ito, S.; Asano, S.; Tanaka, I.; Sato, M.; Kondo, M.; Hasegawa, Y. Regulation of PD-L1 expression by matrix stiffness in lung cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 495, 2344–2349.

- Lu, C.; Redd, P.S.; Lee, J.R.; Savage, N.; Liu, K. The expression profiles and regulation of PD-L1 in tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1247135.

- Altorki, N.K.; Markowitz, G.J.; Gao, D.; Port, J.L.; Saxena, A.; Stiles, B.; McGraw, T.; Mittal, V. The lung microenvironment: An important regulator of tumour growth and metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2019, 19, 9–31.

- Chen, N.; Fang, W.; Lin, Z.; Peng, P.; Wang, J.; Zhan, J.; Hong, S.; Huang, J.; Liu, L.; Sheng, J.; et al. KRAS mutation-induced upregulation of PD-L1 mediates immune escape in human lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2017, 66, 1175–1187.

- Coelho, M.A.; de Carne Trecesson, S.; Rana, S.; Zecchin, D.; Moore, C.; Molina-Arcas, M.; East, P.; Spencer-Dene, B.; Nye, E.; Barnouin, K.; et al. Oncogenic RAS Signaling Promotes Tumor Immunoresistance by Stabilizing PD-L1 mRNA. Immunity 2017, 47, 1083–1099.e6.

- Kataoka, K.; Shiraishi, Y.; Takeda, Y.; Sakata, S.; Matsumoto, M.; Nagano, S.; Maeda, T.; Nagata, Y.; Kitanaka, A.; Mizuno, S.; et al. Aberrant PD-L1 expression through 3′-UTR disruption in multiple cancers. Nature 2016, 534, 402–406.

- Glorieux, C.; Xia, X.; He, Y.Q.; Hu, Y.; Cremer, K.; Robert, A.; Liu, J.; Wang, F.; Ling, J.; Chiao, P.J.; et al. Regulation of PD-L1 expression in K-ras-driven cancers through ROS-mediated FGFR1 signaling. Redox Biol. 2021, 38, 101780.