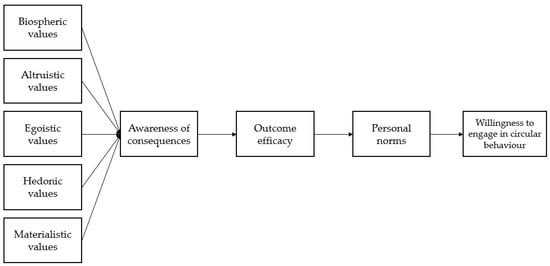

The apparel industry causes environmental problems, particularly due to the shortening life cycle of garments and fast-fashion’s throw-away culture. The circular economy provides solutions to minimise and prevent these problems through innovative circular business models, which require changes in consumer behaviours. With the lens of environmental psychology, we analyse consumers’ willingness to acquire circular apparel considering four approaches on clothing life-cycle extension. We conducted an online questionnaire among Brazilian and Dutch consumers and tested if the Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) theory can explain the willingness of consumers to purchase circular apparel. Our results indicate that, overall, the variables from the VBN theory explain circular behaviour in the apparel industry and that the paths suggested by the model are supported by our analyses. Additionally, we tested and found that when all of the variables from the VBN theory were controlled for, materialistic values did not explain circular behaviours in the apparel industry among Brazilian respondents. However, they had a positive influence on some circular apparel behaviours among Dutch consumers. Overall, materialistic values did not play an important role in predicting willingness to consume circular clothing. Furthermore, the results suggest that the VBN theory predicts willingness to consume circular apparel better in the Netherlands compared to Brazil, suggesting that this behaviour may be perceived as more effortful for the Brazilian population. However, we highlight the need for future research.

- circular economy

- environmental psychology

- consumer behaviour

- life-cycle extension

1. Introduction

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su14020618

References

- Keane, J.; te Velde, D.W.. The Role of Textile and Clothing Industries in Growth and Development Strategies; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2008; pp. 72.

- Fujita, R.M.L.; Jorente, M.J.; A Indústria Têxtil no Brasil: Uma perspectiva histórica e cultural.. ModaPalavra e-Periódico 2016, 8, 153-174, .

- A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future. . Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Retrieved 2022-1-10

- Claudio, L.; Waste Couture: Environmental Impact of the Clothing Industry. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 449-454, https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.115-a449.

- Saito, Y.; Consumer Aesthetics and Environmental Ethics: Problems and Possibilities.. J. Aesthet. Art Crit. 2018, 76, 429-439, https://doi.org/10.1111/jaac.12594.

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; Perry, P.; Rissanen, T.; Gwilt, A.; The environmental price of fast fashion.. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 189-200, htt10.1038/s43017-020-0039-9.

- Armstrong, C.M.J.; Kang, J.; Lang, C.; Clothing style confidence: The development and validation of a multidimensional scale to explore product longevity.. J. Consum. Behav. 2018, 17, 553-568, https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1739.

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S.; A review on circular economy: the expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11-32, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.09.007.

- Ritzén, S.; Sandström, G.Ö. Barriers to the Circular Economy–Integration of Perspectives and Domains. In Proceedings of the 9th CIRP IPSS Conference: Circular Perspectives on Product/Service-Systems, Copenhagen, Denmark, 19–21 June 2017.

- Boulding, K. The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth. In Environmental Quality in a Growing Economy, Resources for the Future; Jarrett, H., Ed.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1966; pp. 3–14.

- Stahel, W.R. The product life factor. In An Inquiry into the Nature of Sustainable Societies: The Role of the Private Sector; Houston Area Research Center: The Woodlands, TX, USA, 1982.

- Pearce, D.W.; Turner, R.K. Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment; Harvester Wheatsheaf: Hemel Hempstead, UK, 1989.

- Blomsma, F.; Brennan, G. The Emergence of Circular Economy: A New Framing around Prolonging Resource Productivity. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 603–614.

- Haas, W.; Krausmann, F.; Wiedenhofer, D.; Heinz, M. How Circular is the Global Economy? An Assessment of Material Flows, Waste Production, and Recycling in the European Union and the World in 2005. J. Ind. Ecol. 2015, 19, 765–777.

- Murray, A.; Skene, K.; Haynes, K. The Circular Economy: An Interdisciplinary Exploration of the Concept and Application in a Global Context. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 369–380.

- Kirchher, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232.

- Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Jaca, C.; Ormazabal, M. Towards a consensus on the circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 179, 605–615.

- BSI–British Standards Institution. BS 8001:2017. Framework for Implementing the Principles of the Circular Economy in Organizations–Guide; The British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2017.

- Chamberlin, L.; Boks, C. Marketing Approaches for a Circular Economy: Using Design Frameworks to Interpret Online Communication. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2070.

- Linder, M.; Williander, M. Circular Business Model Innovation: Inherent Uncertainties. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 182–196.

- Mentink, B. Circular Business Model Innovation: A Process Framework and a Tool for Business Model Innovation in a Circular Economy. Master’s Thesis, TU Delft, Delft, The Netherlands, 2014.

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model. Generation; John Wiley & Sons: Hobroken, NJ, USA, 2010.

- Technology and Trust: How the Sharing Economy is Changing Consumer Behavior. . Quinones, A.; Augustine, A.. Retrieved 2022-1-10

- Botelho, A.; Dias, M.F.; Ferreira, C.; Pinto, L.M.C. The market of electrical and electronic equipment waste in Portugal: Analysis of take-back consumers’ decisions. Waste Manag. Res. 2016, 34, 1074–1080.

- Daae, J.; Chamberlin, L.; Boks, C. Dimensions of Behaviour Change in the context of Designing for a Circular Economy. Des. J. 2018, 21, 521–541.

- Stern, P.C. Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behaviour. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424.

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 10, 221–279.

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.D.; Guagnano, G.; Kalof, L. A Value-Belief-Norm theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism. Res. Hum. Ecol. 1999, 6, 81–97.

- Jansson, J.; Marell, A.; Nordlund, A. Exploring consumer adoption of a high involvement eco-innovation using Value-Belief-Norm theory. J. Consum. Behav. 2011, 10, 51–60.

- van der Werff, E.; Steg, L. The psychology of participation and interest in smart energy systems: Comparing the Value-Belief-Norm theory and the value-identity-personal norm model. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 22, 107–114.

- Johansson, M.; Rahm, J.; Gyllin, M. Landowners’ Participation in Biodiversity Conservation Examined through the Value-Belief-Norm theory. Landsc. Res. 2013, 38, 295–311.

- Yıldırım, B.Ç.; Semiz, G.K. Future Teachers’ Sustainable Water Consumption Behavior: A Test of the Value-Belief-Norm theory. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1558.

- Rossi, E.; Bertassini, A.C.; Ferreira, C.S.; Amaral, W.A.N.; Ometto, A.R. Circular economy indicators for organizations considering sustainability and business models: Plastic, textile and electro-electronic cases. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119137.

- Gomes, G.M.; Moreira, N.; Iritani, D.R.; Amaral, W.A.; Ometo, A.R. Systemic circular innovation: Barriers, windows of opportunity and an analysis of Brazil’s apparel scenario. Fash. Pract. 2021, 1–30.

- Fischer, A.; Pascucci, S. Institutional incentives in circular economy transition: The case of material use in the Dutch textile industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 155, 17–32.