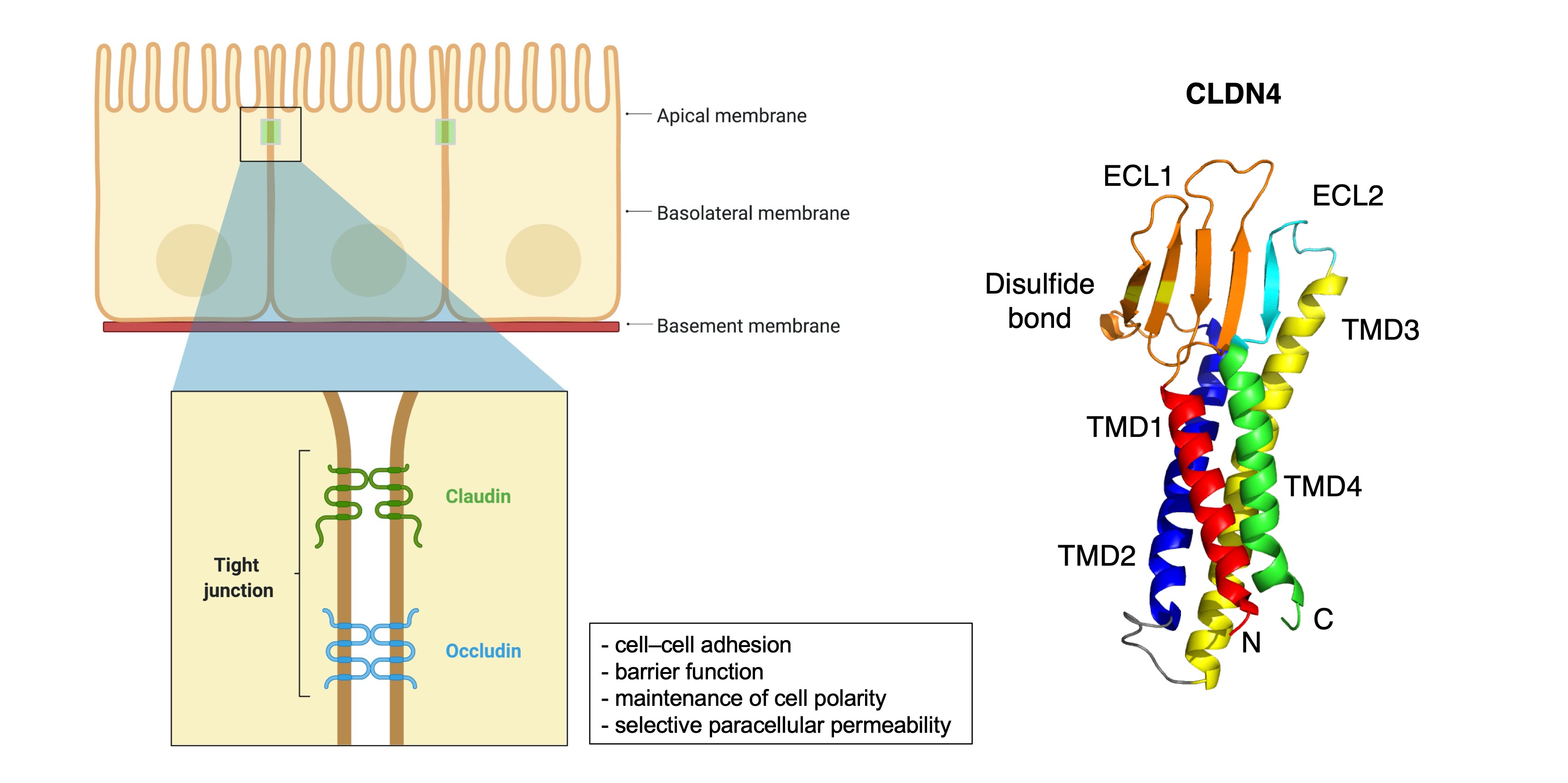

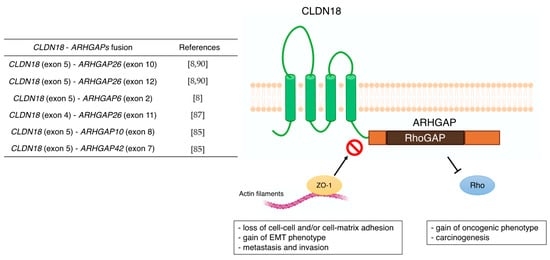

Despite recent improvements in diagnostic ability and treatment strategies, advanced gastric cancer (GC) has a high frequency of recurrence and metastasis, with poor prognosis. To improve the treatment results of GC, the search for new treatment targets from proteins related to epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and cell–cell adhesion is currently being conducted. EMT plays an important role in cancer metastasis and is initiated by the loss of cell–cell adhesion, such as tight junctions (TJs), adherens junctions, desmosomes, and gap junctions. Among these, claudins (CLDNs) are highly expressed in some cancers, including GC. Abnormal expression of CLDN1, CLDN2, CLDN3, CLDN4, CLDN6, CLDN7, CLDN10, CLDN11, CLDN14, CLDN17, CLDN18, and CLDN23 have been reported. Among these, CLDN18 is of particular interest. In The Cancer Genome Atlas, GC was classified into four new molecular subtypes, and CLDN18–ARHGAP fusion was observed in the genomically stable type. An anti-CLDN18.2 antibody drug was recently developed as a therapeutic drug for GC, and the results of clinical trials are highly predictable. Thus, CLDNs are highly expressed in GC as TJs and are expected targets for new antibody drugs.

- gastric cancer

- metastasis

- claudin

- CLDN18

1. Introduction

2. General Information of CLDNs

3. CLDN Expression in GC

3.1. CLDN18

| Type of CLDN | Main Functions, Signaling Molecules Involved, and Clinical Significances in GC | References |

|---|---|---|

| CLDN1 | - correlation with tumor infiltration and metastasis - Akt, Src, and NF-κB signaling pathway - poor prognostic factor |

[39][40] [41][42] [40][43] |

| CLDN2 | - CDX2-dependent targeting relationship with CagA produced from H. pylori | [44] |

| CLDN3 | - correlation with lymph node metastasis - important immunosuppressive regulator |

[45] [46] |

| CLDN4 | - correlation with lymph node metastasis - promoting EMT and infiltration of MMP-2 and MMP-9 |

[47] [48][49][50] |

| CLDN6 | - cell proliferation and migration/infiltration with YAP1 - high expression was positively correlated with decreased OS |

[51] [51][52] |

| CLDN7 | - proliferation in a CagA-and β-catenin-dependent manner - poor prognostic factor |

[53] [54] |

| CLDN10 | - association with metastasis and proliferation | [55][56] |

| CLDN11 | - correlation with H. pylori infection and Borrmann classification, not with lymph node metastasis and TNM stage | [57] |

| CLDN14 | - correlation with lymph node metastasis | [58] |

| CLDN17 | - correlation with lymph node metastasis | [58] |

| CLDN18 | - correlation with metastasis (lymph node, peritoneal, bone, and liver metastasis) - poor prognostic factor - Wnt, β-catenin, CD44, EFNB/ EPHB receptor signals, and HIPPO signals - CLDN18-ARHGAP fusion in genomically stable type - therapeutic target of Claudiximab (IMAB362, Zolbetuximab) |

[59][60] [61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68] [54][69][70] [8] [10][71][72][73] |

| CLDN23 | - poor prognostic factor | [57] |

| Study Name | NCT Number | Phase | Number of Participants | Design | Response Rate | OS | PFS | Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | NCT00909025 | I | 15 | Single-dose escalation study evaluating safety and tolerability | - | - | - | Vomiting |

| PILOT | NCT01671774 | I | 32 | Multiple dose study of IMAB362 with immunomodulation (Zoledronic acid and IL-2) | 11 patients had disease control | 40 weeks | 12.7 weeks | Nausea and vomiting |

| MONO | NCT01197885 | IIa | 54 | Multiple dose study of IMAB362 as monotherapy | Clinical benefit rate: 23% | - | - | Nausea, vomiting, and fatigue |

| FAST | NCT01630083 | IIb | 246 | Randomized EOX vs. IMAB362 + EOX, extended with high-dose IMAB362 + EOX | Objective response rate: 25 vs. 39% | 8.3 vs. 13.0 months | 5.3 vs. 7.5 months | Neutropenia, anemia, weight loss, and vomiting |

| GLOW | NCT03653507 | III | 500 (estimated) | Double-blinded, Randomized, IMAB362 plus CAPOX compared with placebo plus CAPOX as first-line treatment of subjects with CLDN 18.2-positive, HER2-negative locally advanced unresectable or metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma | - | - | - | - |

3.2. CLDN1

3.3. CLDN2

3.4. CLDN3

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers14020290

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249.

- Riihimäki, M.; Hemminki, A.; Sundquist, K.; Sundquist, J.; Hemminki, K. Metastatic Spread in Patients with Gastric Cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 52307–52316.

- Li, W.; Ng, J.M.-K.; Wong, C.C.; Ng, E.K.W.; Yu, J. Molecular Alterations of Cancer Cell and Tumour Microenvironment in Metastatic Gastric Cancer. Oncogene 2018, 37, 4903–4920.

- Lamouille, S.; Xu, J.; Derynck, R. Molecular Mechanisms of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 178–196.

- Acloque, H.; Adams, M.S.; Fishwick, K.; Bronner-Fraser, M.; Nieto, M.A. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transitions: The Importance of Changing Cell State in Development and Disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 1438–1449.

- Milatz, S.; Piontek, J.; Hempel, C.; Meoli, L.; Grohe, C.; Fromm, A.; Lee, I.-F.M.; El-Athman, R.; Günzel, D. Tight Junction Strand Formation by Claudin-10 Isoforms and Claudin-10a/-10b Chimeras. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2017, 1405, 102–115.

- Tabariès, S.; Siegel, P.M. The Role of Claudins in Cancer Metastasis. Oncogene 2017, 36, 1176–1190.

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Gastric Adenocarcinoma. Nature 2014, 513, 202–209.

- Türeci, O.; Sahin, U.; Schulze-Bergkamen, H.; Zvirbule, Z.; Lordick, F.; Koeberle, D.; Thuss-Patience, P.; Ettrich, T.; Arnold, D.; Bassermann, F.; et al. A Multicentre, Phase II a Study of Zolbetuximab as a Single Agent in Patients with Recurrent or Refractory Advanced Adenocarcinoma of the Stomach or Lower Oesophagus: The MONO Study. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1487–1495.

- Sahin, U.; Türeci, Ö.; Manikhas, G.; Lordick, F.; Rusyn, A.; Vynnychenko, I.; Dudov, A.; Bazin, I.; Bondarenko, I.; Melichar, B.; et al. FAST: A Randomised Phase II Study of Zolbetuximab (IMAB362) plus EOX versus EOX Alone for First-Line Treatment of Advanced CLDN18.2-Positive Gastric and Gastro-Oesophageal Adenocarcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 609–619.

- Krause, G.; Winkler, L.; Mueller, S.L.; Haseloff, R.F.; Piontek, J.; Blasig, I.E. Structure and Function of Claudins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1778, 631–645.

- Bhat, A.A.; Syed, N.; Therachiyil, L.; Nisar, S.; Hashem, S.; Macha, M.A.; Yadav, S.K.; Krishnankutty, R.; Muralitharan, S.; Al-Naemi, H.; et al. Claudin-1, A Double-Edged Sword in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 569.

- Tsukita, S.; Furuse, M. The Structure and Function of Claudins, Cell Adhesion Molecules at Tight Junctions. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 915, 129–135.

- Lal-Nag, M.; Morin, P.J. The Claudins. Genome Biol. 2009, 10, 235.

- Colegio, O.R.; Van Itallie, C.M.; McCrea, H.J.; Rahner, C.; Anderson, J.M. Claudins Create Charge-Selective Channels in the Paracellular Pathway between Epithelial Cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2002, 283, C142–C147.

- Angelow, S.; Ahlstrom, R.; Yu, A.S.L. Biology of Claudins. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2008, 295, F867–F876.

- Piontek, J.; Winkler, L.; Wolburg, H.; Müller, S.L.; Zuleger, N.; Piehl, C.; Wiesner, B.; Krause, G.; Blasig, I.E. Formation of Tight Junction: Determinants of Homophilic Interaction between Classic Claudins. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 146–158.

- Huo, L.; Wen, W.; Wang, R.; Kam, C.; Xia, J.; Feng, W.; Zhang, M. Cdc42-Dependent Formation of the ZO-1/MRCKβ Complex at the Leading Edge Controls Cell Migration. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 665–678.

- Kremerskothen, J.; Stölting, M.; Wiesner, C.; Korb-Pap, A.; van Vliet, V.; Linder, S.; Huber, T.B.; Rottiers, P.; Reuzeau, E.; Genot, E.; et al. Zona Occludens Proteins Modulate Podosome Formation and Function. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 505–514.

- Capaldo, C.T.; Koch, S.; Kwon, M.; Laur, O.; Parkos, C.A.; Nusrat, A. Tight Function Zonula Occludens-3 Regulates Cyclin D1-Dependent Cell Proliferation. Mol. Biol. Cell 2011, 22, 1677–1685.

- González-Mariscal, L.; Tapia, R.; Chamorro, D. Crosstalk of Tight Junction Components with Signaling Pathways. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1778, 729–756.

- Tsukita, S.; Furuse, M.; Itoh, M. Multifunctional Strands in Tight Junctions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 2, 285–293.

- Van Itallie, C.M.; Gambling, T.M.; Carson, J.L.; Anderson, J.M. Palmitoylation of Claudins Is Required for Efficient Tight-Junction Localization. J. Cell Sci. 2005, 118, 1427–1436.

- Van Itallie, C.M.; Mitic, L.L.; Anderson, J.M. SUMOylation of Claudin-2. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1258, 60–64.

- Van Itallie, C.M.; Tietgens, A.J.; LoGrande, K.; Aponte, A.; Gucek, M.; Anderson, J.M. Phosphorylation of Claudin-2 on Serine 208 Promotes Membrane Retention and Reduces Trafficking to Lysosomes. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 4902–4912.

- D’Souza, T.; Agarwal, R.; Morin, P.J. Phosphorylation of Claudin-3 at Threonine 192 by CAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase Regulates Tight Junction Barrier Function in Ovarian Cancer Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 26233–26240.

- Stamatovic, S.M.; Dimitrijevic, O.B.; Keep, R.F.; Andjelkovic, A.V. Protein Kinase Calpha-RhoA Cross-Talk in CCL2-Induced Alterations in Brain Endothelial Permeability. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 8379–8388.

- Yamauchi, K.; Rai, T.; Kobayashi, K.; Sohara, E.; Suzuki, T.; Itoh, T.; Suda, S.; Hayama, A.; Sasaki, S.; Uchida, S. Disease-Causing Mutant WNK4 Increases Paracellular Chloride Permeability and Phosphorylates Claudins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 4690–4694.

- Tanaka, M.; Kamata, R.; Sakai, R. EphA2 Phosphorylates the Cytoplasmic Tail of Claudin-4 and Mediates Paracellular Permeability. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 42375–42382.

- Soma, T.; Chiba, H.; Kato-Mori, Y.; Wada, T.; Yamashita, T.; Kojima, T.; Sawada, N. Thr(207) of Claudin-5 Is Involved in Size-Selective Loosening of the Endothelial Barrier by Cyclic AMP. Exp. Cell Res. 2004, 300, 202–212.

- Gyõrffy, H.; Holczbauer, A.; Nagy, P.; Szabó, Z.; Kupcsulik, P.; Páska, C.; Papp, J.; Schaff, Z.; Kiss, A. Claudin Expression in Barrett’s Esophagus and Adenocarcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2005, 447, 961–968.

- Singh, P.; Toom, S.; Huang, Y. Anti-Claudin 18.2 Antibody as New Targeted Therapy for Advanced Gastric Cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 10, 105.

- Ding, L.; Lu, Z.; Lu, Q.; Chen, Y.-H. The Claudin Family of Proteins in Human Malignancy: A Clinical Perspective. Cancer Manag. Res. 2013, 5, 367–375.

- Hu, Y.-J.; Wang, Y.-D.; Tan, F.-Q.; Yang, W.-X. Regulation of Paracellular Permeability: Factors and Mechanisms. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013, 40, 6123–6142.

- Turner, J.R.; Buschmann, M.M.; Romero-Calvo, I.; Sailer, A.; Shen, L. The Role of Molecular Remodeling in Differential Regulation of Tight Junction Permeability. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 36, 204–212.

- Niimi, T.; Nagashima, K.; Ward, J.M.; Minoo, P.; Zimonjic, D.B.; Popescu, N.C.; Kimura, S. Claudin-18, a Novel Downstream Target Gene for the T/EBP/NKX2.1 Homeodomain Transcription Factor, Encodes Lung- and Stomach-Specific Isoforms through Alternative Splicing. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 21, 7380–7390.

- Sahin, U.; Koslowski, M.; Dhaene, K.; Usener, D.; Brandenburg, G.; Seitz, G.; Huber, C.; Türeci, O. Claudin-18 Splice Variant 2 Is a Pan-Cancer Target Suitable for Therapeutic Antibody Development. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 7624–7634.

- Shinozaki, A.; Ushiku, T.; Morikawa, T.; Hino, R.; Sakatani, T.; Uozaki, H.; Fukayama, M. Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated Gastric Carcinoma: A Distinct Carcinoma of Gastric Phenotype by Claudin Expression Profiling. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2009, 57, 775–785.

- Wu, Y.-L.; Zhang, S.; Wang, G.-R.; Chen, Y.-P. Expression Transformation of Claudin-1 in the Process of Gastric Adenocarcinoma Invasion. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 4943–4948.

- Huang, J.; Li, J.; Qu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Liu, B.; Zhu, Z. The Expression of Claudin 1 Correlates with β-Catenin and Is a Prognostic Factor of Poor Outcome in Gastric Cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 44, 1293–1301.

- Huang, J.; Zhang, L.; He, C.; Qu, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Du, T.; Chen, X.; Yu, Y.; Liu, B.; et al. Claudin-1 Enhances Tumor Proliferation and Metastasis by Regulating Cell Anoikis in Gastric Cancer. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 1652–1665.

- Shiozaki, A.; Shimizu, H.; Ichikawa, D.; Konishi, H.; Komatsu, S.; Kubota, T.; Fujiwara, H.; Okamoto, K.; Iitaka, D.; Nakashima, S.; et al. Claudin 1 Mediates Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha-Induced Cell Migration in Human Gastric Cancer Cells. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 17863–17876.

- Eftang, L.L.; Esbensen, Y.; Tannæs, T.M.; Blom, G.P.; Bukholm, I.R.K.; Bukholm, G. Up-Regulation of CLDN1 in Gastric Cancer Is Correlated with Reduced Survival. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 586.

- Song, X.; Chen, H.-X.; Wang, X.-Y.; Deng, X.-Y.; Xi, Y.-X.; He, Q.; Peng, T.-L.; Chen, J.; Chen, W.; Wong, B.C.-Y.; et al. H. Pylori-Encoded CagA Disrupts Tight Junctions and Induces Invasiveness of AGS Gastric Carcinoma Cells via Cdx2-Dependent Targeting of Claudin-2. Cell Immunol. 2013, 286, 22–30.

- Wang, H.; Yang, X. The Expression Patterns of Tight Junction Protein Claudin-1, -3, and -4 in Human Gastric Neoplasms and Adjacent Non-Neoplastic Tissues. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 881–887.

- Ren, F.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, M.; Zhu, S.; Liu, B.; Bukhari, I.; Zhang, K.; Wu, W.; Fu, Y.; Yu, Y.; et al. Immune Infiltration Profiling in Gastric Cancer and Their Clinical Implications. Cancer Sci. 2021, 112, 3569–3584.

- Chen, X.; Zhao, J.; Li, A.; Gao, P.; Sun, J.; Song, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, P.; Wang, Z. Clinicopathological Significance of Claudin 4 Expression in Gastric Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. OncoTargets Ther. 2016, 9, 3205–3212.

- Agarwal, R.; D’Souza, T.; Morin, P.J. Claudin-3 and Claudin-4 Expression in Ovarian Epithelial Cells Enhances Invasion and Is Associated with Increased Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 Activity. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 7378–7385.

- Lin, X.; Shang, X.; Manorek, G.; Howell, S.B. Regulation of the Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition by Claudin-3 and Claudin-4. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67496.

- Hwang, T.-L.; Lee, L.-Y.; Wang, C.-C.; Liang, Y.; Huang, S.-F.; Wu, C.-M. Claudin-4 Expression Is Associated with Tumor Invasion, MMP-2 and MMP-9 Expression in Gastric Cancer. Exp. Ther. Med. 2010, 1, 789–797.

- Kohmoto, T.; Masuda, K.; Shoda, K.; Takahashi, R.; Ujiro, S.; Tange, S.; Ichikawa, D.; Otsuji, E.; Imoto, I. Claudin-6 Is a Single Prognostic Marker and Functions as a Tumor-Promoting Gene in a Subgroup of Intestinal Type Gastric Cancer. Gastric Cancer 2020, 23, 403–417.

- Yu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, G.; Xu, J. CLDN6 Promotes Tumor Progression through the YAP1-Snail1 Axis in Gastric Cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 949.

- Wroblewski, L.E.; Piazuelo, M.B.; Chaturvedi, R.; Schumacher, M.; Aihara, E.; Feng, R.; Noto, J.M.; Delgado, A.; Israel, D.A.; Zavros, Y.; et al. Helicobacter Pylori Targets Cancer-Associated Apical-Junctional Constituents in Gastroids and Gastric Epithelial Cells. Gut 2015, 64, 720–730.

- Jun, K.-H.; Kim, J.-H.; Jung, J.-H.; Choi, H.-J.; Chin, H.-M. Expression of Claudin-7 and Loss of Claudin-18 Correlate with Poor Prognosis in Gastric Cancer. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 156–162.

- Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, A.; Li, Q.; Zhou, M.; Li, T. CLDN10 Promotes a Malignant Phenotype of Osteosarcoma Cells via JAK1/Stat1 Signaling. J. Cell Commun. Signal 2019, 13, 395–405.

- Sun, H.; Cui, C.; Xiao, F.; Wang, H.; Xu, J.; Shi, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, X.; Yang, X.; et al. MiR-486 Regulates Metastasis and Chemosensitivity in Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Targeting CLDN10 and CITRON. Hepatol. Res. 2015, 45, 1312–1322.

- Lu, Y.; Jing, J.; Sun, L.; Gong, Y.; Chen, M.; Wang, Z.; Sun, M.; Yuan, Y. Expression of Claudin-11, -23 in Different Gastric Tissues and Its Relationship with the Risk and Prognosis of Gastric Cancer. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174476.

- Gao, M.; Li, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, G. The Distinct Expression Patterns of Claudin-10, -14, -17 and E-Cadherin between Adjacent Non-Neoplastic Tissues and Gastric Cancer Tissues. Diagn. Pathol. 2013, 8, 205.

- Kim, S.R.; Shin, K.; Park, J.M.; Lee, H.H.; Song, K.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, B.; Kim, S.-Y.; Seo, J.; Kim, J.-O.; et al. Clinical Significance of CLDN18.2 Expression in Metastatic Diffuse-Type Gastric Cancer. J. Gastric. Cancer 2020, 20, 408–420.

- Pellino, A.; Brignola, S.; Riello, E.; Niero, M.; Murgioni, S.; Guido, M.; Nappo, F.; Businello, G.; Sbaraglia, M.; Bergamo, F.; et al. Association of CLDN18 Protein Expression with Clinicopathological Features and Prognosis in Advanced Gastric and Gastroesophageal Junction Adenocarcinomas. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 1095.

- Franco, A.T.; Israel, D.A.; Washington, M.K.; Krishna, U.; Fox, J.G.; Rogers, A.B.; Neish, A.S.; Collier-Hyams, L.; Perez-Perez, G.I.; Hatakeyama, M.; et al. Activation of Beta-Catenin by Carcinogenic Helicobacter Pylori. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 10646–10651.

- Nagy, T.A.; Wroblewski, L.E.; Wang, D.; Piazuelo, M.B.; Delgado, A.; Romero-Gallo, J.; Noto, J.; Israel, D.A.; Ogden, S.R.; Correa, P.; et al. β-Catenin and P120 Mediate PPARδ-Dependent Proliferation Induced by Helicobacter Pylori in Human and Rodent Epithelia. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 553–564.

- Khurana, S.S.; Riehl, T.E.; Moore, B.D.; Fassan, M.; Rugge, M.; Romero-Gallo, J.; Noto, J.; Peek, R.M.; Stenson, W.F.; Mills, J.C. The Hyaluronic Acid Receptor CD44 Coordinates Normal and Metaplastic Gastric Epithelial Progenitor Cell Proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 16085–16097.

- Uchiyama, S.; Saeki, N.; Ogawa, K. Aberrant EphB/Ephrin-B Expression in Experimental Gastric Lesions and Tumor Cells. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 453–464.

- Wong, S.S.; Kim, K.-M.; Ting, J.C.; Yu, K.; Fu, J.; Liu, S.; Cristescu, R.; Nebozhyn, M.; Gong, L.; Yue, Y.G.; et al. Genomic Landscape and Genetic Heterogeneity in Gastric Adenocarcinoma Revealed by Whole-Genome Sequencing. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5477.

- Ma, L.-G.; Bian, S.-B.; Cui, J.-X.; Xi, H.-Q.; Zhang, K.-C.; Qin, H.-Z.; Zhu, X.-M.; Chen, L. LKB1 Inhibits the Proliferation of Gastric Cancer Cells by Suppressing the Nuclear Translocation of Yap and β-Catenin. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2016, 37, 1039–1048.

- Jiao, S.; Wang, H.; Shi, Z.; Dong, A.; Zhang, W.; Song, X.; He, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, W.; et al. A Peptide Mimicking VGLL4 Function Acts as a YAP Antagonist Therapy against Gastric Cancer. Cancer Cell 2014, 25, 166–180.

- Suzuki, K.; Sentani, K.; Tanaka, H.; Yano, T.; Suzuki, K.; Oshima, M.; Yasui, W.; Tamura, A.; Tsukita, S. Deficiency of Stomach-Type Claudin-18 in Mice Induces Gastric Tumor Formation Independent of H Pylori Infection. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 8, 119–142.

- Sanada, Y.; Oue, N.; Mitani, Y.; Yoshida, K.; Nakayama, H.; Yasui, W. Down-Regulation of the Claudin-18 Gene, Identified through Serial Analysis of Gene Expression Data Analysis, in Gastric Cancer with an Intestinal Phenotype. J. Pathol. 2006, 208, 633–642.

- Matsuda, Y.; Semba, S.; Ueda, J.; Fuku, T.; Hasuo, T.; Chiba, H.; Sawada, N.; Kuroda, Y.; Yokozaki, H. Gastric and Intestinal Claudin Expression at the Invasive Front of Gastric Carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2007, 98, 1014–1019.

- Sahin, U.; Schuler, M.; Richly, H.; Bauer, S.; Krilova, A.; Dechow, T.; Jerling, M.; Utsch, M.; Rohde, C.; Dhaene, K.; et al. A Phase I Dose-Escalation Study of IMAB362 (Zolbetuximab) in Patients with Advanced Gastric and Gastro-Oesophageal Junction Cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2018, 100, 17–26.

- Sahin, U.; Al-Batran, S.-E.; Hozaeel, W.; Zvirbule, Z.; Freiberg-Richter, J.; Lordick, F.; Just, M.; Bitzer, M.; Thuss-Patience, P.C.; Krilova, A.; et al. IMAB362 plus Zoledronic Acid (ZA) and Interleukin-2 (IL-2) in Patients (Pts) with Advanced Gastroesophageal Cancer (GEC): Clinical Activity and Safety Data from the PILOT Phase I Trial. JCO 2015, 33, e15079.

- Astellas Pharma Global Development, Inc. A Phase 3, Global, Multi-Center, Double-Blind, Randomized, Efficacy Study of Zolbetuximab (IMAB362) Plus CAPOX Compared With Placebo Plus CAPOX as First-Line Treatment of Subjects with Claudin (CLDN) 18.2-Positive, HER2-Negative, Locally Advanced Unresectable or Metastatic Gastric or Gastroesophageal Junction (GEJ) Adenocarcinoma. 2021. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Correa, P. Human Gastric Carcinogenesis: A Multistep and Multifactorial Process--First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Cancer Res. 1992, 52, 6735–6740.

- Correa, P.; Houghton, J. Carcinogenesis of Helicobacter Pylori. Gastroenterology 2007, 133, 659–672.

- Oshima, T.; Shan, J.; Okugawa, T.; Chen, X.; Hori, K.; Tomita, T.; Fukui, H.; Watari, J.; Miwa, H. Down-Regulation of Claudin-18 Is Associated with the Proliferative and Invasive Potential of Gastric Cancer at the Invasive Front. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74757.

- Hagen, S.J.; Ang, L.-H.; Zheng, Y.; Karahan, S.N.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.E.; Caron, T.J.; Gad, A.P.; Muthupalani, S.; Fox, J.G. Loss of Tight Junction Protein Claudin 18 Promotes Progressive Neoplasia Development in Mouse Stomach. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 1852–1867.

- Petersen, C.P.; Mills, J.C.; Goldenring, J.R. Murine Models of Gastric Corpus Preneoplasia. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 3, 11–26.

- Hayashi, D.; Tamura, A.; Tanaka, H.; Yamazaki, Y.; Watanabe, S.; Suzuki, K.; Suzuki, K.; Sentani, K.; Yasui, W.; Rakugi, H.; et al. Deficiency of Claudin-18 Causes Paracellular H+ Leakage, up-Regulation of Interleukin-1β, and Atrophic Gastritis in Mice. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 292–304.

- Dottermusch, M.; Krüger, S.; Behrens, H.-M.; Halske, C.; Röcken, C. Expression of the Potential Therapeutic Target Claudin-18.2 Is Frequently Decreased in Gastric Cancer: Results from a Large Caucasian Cohort Study. Virchows Arch. 2019, 475, 563–571.

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, D.; Gong, T.; Xu, R.; Gao, J. Analysis of the Expression and Genetic Alteration of CLDN18 in Gastric Cancer. Aging 2020, 12, 14271–14284.

- Coati, I.; Lotz, G.; Fanelli, G.N.; Brignola, S.; Lanza, C.; Cappellesso, R.; Pellino, A.; Pucciarelli, S.; Spolverato, G.; Guzzardo, V.; et al. Claudin-18 Expression in Oesophagogastric Adenocarcinomas: A Tissue Microarray Study of 523 Molecularly Profiled Cases. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 121, 257–263.

- Li, W.-T.; Jeng, Y.-M.; Yang, C.-Y. Claudin-18 as a Marker for Identifying the Stomach and Pancreatobiliary Tract as the Primary Sites of Metastatic Adenocarcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2020, 44, 1643–1648.

- Kakiuchi, M.; Nishizawa, T.; Ueda, H.; Gotoh, K.; Tanaka, A.; Hayashi, A.; Yamamoto, S.; Tatsuno, K.; Katoh, H.; Watanabe, Y.; et al. Recurrent Gain-of-Function Mutations of RHOA in Diffuse-Type Gastric Carcinoma. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 583–587.

- Yao, F.; Kausalya, J.P.; Sia, Y.Y.; Teo, A.S.M.; Lee, W.H.; Ong, A.G.M.; Zhang, Z.; Tan, J.H.J.; Li, G.; Bertrand, D.; et al. Recurrent Fusion Genes in Gastric Cancer: CLDN18-ARHGAP26 Induces Loss of Epithelial Integrity. Cell Rep. 2015, 12, 272–285.

- Tanaka, A.; Ishikawa, S.; Ushiku, T.; Yamazawa, S.; Katoh, H.; Hayashi, A.; Kunita, A.; Fukayama, M. Frequent CLDN18-ARHGAP Fusion in Highly Metastatic Diffuse-Type Gastric Cancer with Relatively Early Onset. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 29336–29350.

- Nakayama, I.; Shinozaki, E.; Sakata, S.; Yamamoto, N.; Fujisaki, J.; Muramatsu, Y.; Hirota, T.; Takeuchi, K.; Takahashi, S.; Yamaguchi, K.; et al. Enrichment of CLDN18-ARHGAP Fusion Gene in Gastric Cancers in Young Adults. Cancer Sci. 2019, 110, 1352–1363.

- Lauren, P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: Diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 1965, 64, 31–49.

- Shu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Hou, Q.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, J.; Song, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, D.; Chen, X.; et al. Prognostic Significance of Frequent CLDN18-ARHGAP26/6 Fusion in Gastric Signet-Ring Cell Cancer. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2447.

- Ushiku, T.; Arnason, T.; Ban, S.; Hishima, T.; Shimizu, M.; Fukayama, M.; Lauwers, G.Y. Very Well-Differentiated Gastric Carcinoma of Intestinal Type: Analysis of Diagnostic Criteria. Mod. Pathol. 2013, 26, 1620–1631.

- Okamoto, N.; Kawachi, H.; Yoshida, T.; Kitagaki, K.; Sekine, M.; Kojima, K.; Kawano, T.; Eishi, Y. “Crawling-Type” Adenocarcinoma of the Stomach: A Distinct Entity Preceding Poorly Differentiated Adenocarcinoma. Gastric. Cancer 2013, 16, 220–232.

- Hashimoto, T.; Ogawa, R.; Tang, T.-Y.; Yoshida, H.; Taniguchi, H.; Katai, H.; Oda, I.; Sekine, S. RHOA Mutations and CLDN18-ARHGAP Fusions in Intestinal-Type Adenocarcinoma with Anastomosing Glands of the Stomach. Mod. Pathol. 2019, 32, 568–575.

- Fukata, M.; Kaibuchi, K. Rho-Family GTPases in Cadherin-Mediated Cell-Cell Adhesion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 2, 887–897.

- Wang, K.; Yuen, S.T.; Xu, J.; Lee, S.P.; Yan, H.H.N.; Shi, S.T.; Siu, H.C.; Deng, S.; Chu, K.M.; Law, S.; et al. Whole-Genome Sequencing and Comprehensive Molecular Profiling Identify New Driver Mutations in Gastric Cancer. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 573–582.

- Kataoka, K.; Ogawa, S. Variegated RHOA Mutations in Human Cancers. Exp. Hematol. 2016, 44, 1123–1129.

- Zhang, H.; Schaefer, A.; Wang, Y.; Hodge, R.G.; Blake, D.R.; Diehl, J.N.; Papageorge, A.G.; Stachler, M.D.; Liao, J.; Zhou, J.; et al. Gain-of-Function RHOA Mutations Promote Focal Adhesion Kinase Activation and Dependency in Diffuse Gastric Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 288–305.

- Klamp, T.; Schumacher, J.; Huber, G.; Kühne, C.; Meissner, U.; Selmi, A.; Hiller, T.; Kreiter, S.; Markl, J.; Türeci, Ö.; et al. Highly Specific Auto-Antibodies against Claudin-18 Isoform 2 Induced by a Chimeric HBcAg Virus-like Particle Vaccine Kill Tumor Cells and Inhibit the Growth of Lung Metastases. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 516–527.

- Micke, P.; Mattsson, J.S.M.; Edlund, K.; Lohr, M.; Jirström, K.; Berglund, A.; Botling, J.; Rahnenfuehrer, J.; Marincevic, M.; Pontén, F.; et al. Aberrantly Activated Claudin 6 and 18.2 as Potential Therapy Targets in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 135, 2206–2214.

- Wöll, S.; Schlitter, A.M.; Dhaene, K.; Roller, M.; Esposito, I.; Sahin, U.; Türeci, Ö. Claudin 18.2 Is a Target for IMAB362 Antibody in Pancreatic Neoplasms. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 134, 731–739.

- Türeci, O.; Koslowski, M.; Helftenbein, G.; Castle, J.; Rohde, C.; Dhaene, K.; Seitz, G.; Sahin, U. Claudin-18 Gene Structure, Regulation, and Expression Is Evolutionary Conserved in Mammals. Gene 2011, 481, 83–92.

- Sentani, K.; Oue, N.; Tashiro, T.; Sakamoto, N.; Nishisaka, T.; Fukuhara, T.; Taniyama, K.; Matsuura, H.; Arihiro, K.; Ochiai, A.; et al. Immunohistochemical Staining of Reg IV and Claudin-18 Is Useful in the Diagnosis of Gastrointestinal Signet Ring Cell Carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2008, 32, 1182–1189.

- Jiang, H.; Shi, Z.; Wang, P.; Wang, C.; Yang, L.; Du, G.; Zhang, H.; Shi, B.; Jia, J.; Li, Q.; et al. Claudin18.2-Specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor Engineered T Cells for the Treatment of Gastric Cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 409–418.

- Zhu, G.; Foletti, D.; Liu, X.; Ding, S.; Melton Witt, J.; Hasa-Moreno, A.; Rickert, M.; Holz, C.; Aschenbrenner, L.; Yang, A.H.; et al. Targeting CLDN18.2 by CD3 Bispecific and ADC Modalities for the Treatments of Gastric and Pancreatic Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8420.

- Fan, L.; Chong, X.; Zhao, M.; Jia, F.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, X.; Huang, Q.; Li, P.; Yang, Y.; et al. Ultrasensitive Gastric Cancer Circulating Tumor Cellular CLDN18.2 RNA Detection Based on a Molecular Beacon. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 665–670.

- The Human Protein Atlas. Available online: https://www.proteinatlas.org/ (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Resnick, M.B.; Gavilanez, M.; Newton, E.; Konkin, T.; Bhattacharya, B.; Britt, D.E.; Sabo, E.; Moss, S.F. Claudin Expression in Gastric Adenocarcinomas: A Tissue Microarray Study with Prognostic Correlation. Hum. Pathol. 2005, 36, 886–892.

- Soini, Y.; Tommola, S.; Helin, H.; Martikainen, P. Claudins 1, 3, 4 and 5 in Gastric Carcinoma, Loss of Claudin Expression Associates with the Diffuse Subtype. Virchows Arch. 2006, 448, 52–58.

- Kinugasa, T.; Huo, Q.; Higashi, D.; Shibaguchi, H.; Kuroki, M.; Tanaka, T.; Futami, K.; Yamashita, Y.; Hachimine, K.; Maekawa, S.; et al. Selective Up-Regulation of Claudin-1 and Claudin-2 in Colorectal Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2007, 27, 3729–3734.

- Kim, T.H.; Huh, J.H.; Lee, S.; Kang, H.; Kim, G.I.; An, H.J. Down-Regulation of Claudin-2 in Breast Carcinomas Is Associated with Advanced Disease. Histopathology 2008, 53, 48–55.

- Song, X.; Li, X.; Tang, Y.; Chen, H.; Wong, B.; Wang, J.; Chen, M. Expression of Claudin-2 in the Multistage Process of Gastric Carcinogenesis. Histol. Histopathol. 2008, 23, 673–682.

- Xin, S.; Huixin, C.; Benchang, S.; Aiping, B.; Jinhui, W.; Xiaoyan, L.; Yu, W.B.C.; Minhu, C. Expression of Cdx2 and Claudin-2 in the Multistage Tissue of Gastric Carcinogenesis. Oncology 2007, 73, 357–365.

- Aung, P.P.; Mitani, Y.; Sanada, Y.; Nakayama, H.; Matsusaki, K.; Yasui, W. Differential Expression of Claudin-2 in Normal Human Tissues and Gastrointestinal Carcinomas. Virchows Arch. 2006, 448, 428–434.

- Lin, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wang, L.; Lu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Yang, M.; Jin, X.; et al. The Distinct Expression Patterns of Claudin-2, -6, and -11 between Human Gastric Neoplasms and Adjacent Non-Neoplastic Tissues. Diagn. Pathol. 2013, 8, 133.

- Okugawa, T.; Oshima, T.; Chen, X.; Hori, K.; Tomita, T.; Fukui, H.; Watari, J.; Matsumoto, T.; Miwa, H. Down-Regulation of Claudin-3 Is Associated with Proliferative Potential in Early Gastric Cancers. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2012, 57, 1562–1567.

- Jung, H.; Jun, K.H.; Jung, J.H.; Chin, H.M.; Park, W.B. The Expression of Claudin-1, Claudin-2, Claudin-3, and Claudin-4 in Gastric Cancer Tissue. J. Surg. Res. 2011, 167, e185–e191.

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, W.; Chen, S.; Chen, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, S. Methylation of the Claudin-3 Promoter Predicts the Prognosis of Advanced Gastric Adenocarcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 40, 49–60.