Metabolic Obesity in People with Normal Body Weight (MONW) has been observed for the first time in 1981 Neil Ruderman, describing a case of patients with symptoms indicative of the metabolic syndromes — reduced insulin sensitivity, hypertension, T2DM, and hypertriglyceridemia — despite normal body mass index (BMI). The primary diagnostic criteria were complex and required the use of tests not routinely used in healthy subjects. In later years, the diagnosis was based on the criteria of classic metabolic syndrome (MetS). Currently, new criteria are being searched for that will allow for a quick and accurate diagnosis of the MONW.

- MONW

- obesity

- diagnostic criteria

1. Introduction

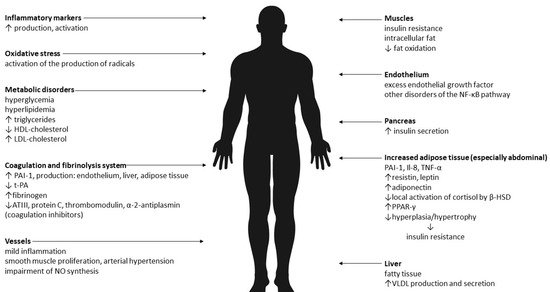

2. Biological Mechanisms of MONW

3. Primary criteria for MONW

| Points | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| 1 | triglycerides level > 100–150 mg/dL blood presure 125–140/85–90 mmHg weight gain: >4 after 18 years for women and 21 years for men BMI: 23–25 kg/m2 waist: 71.1–76.2 for women and 86.3–91.4 for men ethnicity: black women, Japanese-Americans, Latinos, Melanesians, Polynesians, New Zealand Maoris |

| 2 | impaired fasting glucose (110–125 mg/dL) triglycerides level > 150 mg/dL blood presure > 140/90 mmHg essential hypertension (under age 60 years) premature coronary heart disease (under age 60 years) low birth weight (<2.5 kg) inactivity (<90 min aerobic exercise/week) weight gain: >8 after 18 years for women and 21 years for men BMI: 25–27 kg/m2 waist: >76.2 for women and >91.4 for men uric acid (>8 mg/dL) ethnicity: Indians, Australian aborigines, Micronesians, Naruans |

| 3 | gestational diabetes triglycerides level > 150 mg/dL and HDL cholesterol < 35 mg/dL type 2 diabetes mellitus or impaired glucose tolerance hypertriglyceridemia weight gain: >12 after 18 years for women and 21 years for men premature coronary heart disease (under age 60 years) ethnicity: some American Indian tribes |

| 4 | type 2 diabetes mellitus impaired glucose tolerance polycystic ovaries |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijerph19020624

References

- Kawalec, A.; Kawalec, A. Analysis of the body composition of young adults and the frequency of occurrence of so-called normal weight obesity: A pilot study. Nurs. Public Health 2019, 9, 167–171.

- WHO. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Jones, A.; Tovee, M.; Cutler, L.; Parkinson, K.; Ells, L.; Araujo-Soares, V.; Pearce, M.; Mann, K.; Scott, D.; Harris, J.; et al. Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years. Yearb. Paediatr. Endocrinol. 2018, 15.

- Ward, Z.J.; Bleich, S.N.; Cradock, A.L.; Barrett, J.L.; Giles, C.M.; Flax, C.; Long, M.W.; Gortmaker, S.L. Projected U.S. State-Level Prevalence of Adult Obesity and Severe Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2440–2450.

- Ahmed, B.; Sultana, R.; Greene, M.W. Adipose tissue and insulin resistance in obese. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 137, 111315.

- Dżygadło, B.; Łepecka-Klusek, C.; Pilewski, B. Use of bioelectrical impedance analysis in prevention and treatment of overweight and obesity. Probl. Hig. Epidemiol. 2012, 93, 274–280.

- Bosello, O.; Donataccio, M.P.; Cuzzolaro, M. Obesity or obesities? Controversies on the association between body mass index and premature mortality. Eat. Weight Disord. 2016, 21, 165–174.

- Ibrahim, M.M. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: Structural and functional differences. Obes. Rev. 2010, 11, 11–18.

- Cnop, M.; Landchild, M.J.; Vidal, J.; Havel, P.J.; Knowles, N.G.; Carr, D.R.; Wang, F.; Hull, R.L.; Boyko, E.J.; Retzlaff, B.M.; et al. The concurrent accumulation of intra-abdominal and subcutaneous fat explains the association between insulin resistance and plasma leptin concentrations: Distinct metabolic effects of two fat compartments. Diabetes 2002, 51, 1005–1015.

- Kokot, I.M.; Pawlik-Sobecka, L.; Płaczkowska, S.; Żółcińska-Wilczyńska, M.; Piwowar, A. The relationship between total body fat and distribution of body fat mass and markers of insulin resistance in young women with normal weight—A pilot study. Clin. Diabetol. 2016, 5, 41–48.

- Wedell-Neergaard, A.-S.; Lang Lehrskov, L.; Christensen, R.H.; Legaard, G.E.; Dorph, E.; Larsen, M.K.; Launbo, N.; Fagerlind, S.R.; Seide, S.K.; Nymand, S.; et al. Exercise-Induced Changes in Visceral Adipose Tissue Mass Are Regulated by IL-6 Signaling: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 844–855.

- Mongraw-Chaffin, M.; Allison, M.A.; Burke, G.L.; Criqui, M.H.; Matsushita, K.; Ouyang, P.; Shah, R.V.; Shay, C.M.; Anderson, C.A.M. CT-derived body fat distribution and incident cardiovascular disease: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 4173–4183.

- Ruderman, N.B.; Schneider, S.H.; Berchtold, P. The “metabolically-obese,” normal-weight individual. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1981, 34, 1617–1621.

- Katsuki, A.; Sumida, Y.; Urakawa, H.; Gabazza, E.C.; Murashima, S.; Maruyama, N.; Morioka, K.; Nakatani, K.; Yano, Y.; Adachi, Y. Increased Visceral Fat and Serum Levels of Triglyceride Are Associated With Insulin Resistance in Japanese Metabolically Obese, Normal Weight Subjects With Normal Glucose Tolerance. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 2341–2344.

- Miazgowski, T.; Safranow, K.; Krzyżanowska-Świniarska, B.; Iskierska, K.; Widecka, K. Adiponectin, visfatin and regional fat depots in normal weight obese premenopausal women. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 43, 783–790.

- De Lorenzo, A.; Del Gobbo, V.; Premrov, M.G.; Bigioni, M.; Galvano, F.; Di Renzo, L. Normal-weight obese syndrome: Early inflammation? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 40–45.

- Katsuki, A.; Sumida, Y.; Urakawa, H.; Gabazza, E.C.; Murashima, S.; Nakatani, K.; Yano, Y.; Adachi, Y. Increased Oxidative Stress Is Associated With Serum Levels of Triglyceride, Insulin Resistance, and Hyperinsulinemia in Japanese Metabolically Obese, Normal-Weight Men. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 631–632.

- Dvorak, R.V.; DeNino, W.F.; Ades, P.A.; Poehlman, E.T. Phenotypic characteristics associated with insulin resistance in metabolically obese but normal-weight young women. Diabetes 1999, 48, 2210–2214.

- Conus, F.; Allison, D.B.; Rabasa-Lhoret, R.; St-Onge, M.; St-Pierre, D.H.; Tremblay-Lebeau, A.; Poehlman, E.T. Metabolic and behavioral characteristics of metabolically obese but normal-weight women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 5013–5020.

- Stefan, N.; Schick, F.; Häring, H.U. Causes, Characteristics, and Consequences of Metabolically Unhealthy Normal Weight in Humans. Cell Metab. 2017, 26, 292–300.

- Zaid, H.; Antonescu, C.N.; Randhawa, V.K.; Klip, A. Insulin action on glucose transporters through molecular switches, tracks and tethers. Biochem. J. 2008, 413, 201–215.

- Davis, R.J. Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases. Cell 2000, 103, 239–252.

- Kershaw, E.E.; Flier, J.S. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 2548–2556.

- Poirier, P.; Lemieux, I.; Mauriège, P.; Dewailly, E.; Blanchet, C.; Bergeron, J.; Després, J.P. Impact of waist circumference on the relationship between blood pressure and insulin: The Quebec health survey. Hypertension 2005, 45, 363–367.

- Poirier, P.; Giles, T.D.; Bray, G.A.; Hong, Y.; Stern, J.S.; Pi-Sunyer, F.X.; Eckel, R.H. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: Pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: An update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on obesity and heart disease from the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical. Circulation 2006, 113, 898–918.

- Ceriello, A.; Motz, E. Is Oxidative Stress the Pathogenic Mechanism Underlying Insulin Resistance, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease? The Common Soil Hypothesis Revisited. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004, 24, 816–823.

- Hyun, Y.J.; Koh, S.J.; Chae, J.S.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, O.Y.; Lim, H.H.; Jang, Y.; Park, S.; Ordovas, J.M.; Lee, J.H. Atherogenecity of LDL and unfavorable adipokine profile in metabolically obese, normal-weight woman. Obesity 2008, 16, 784–789.

- Hajian-Tilaki, K.; Heidari, B. Metabolically healthy obese and unhealthy normal weight in Iranian adult population: Prevalence and the associated factors. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2017, 12, 129–134.

- Lee, K. Metabolically obese but normal weight (MONW) and metabolically healthy but obese (MHO) phenotypes in Koreans: Characteristics and health behaviors. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr 2009, 18, 280–284.

- Wang, B.; Zhuang, R.; Luo, X.; Yin, L.; Pang, C.; Feng, T.; You, H.; Zhai, Y.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, L.; et al. Prevalence of Metabolically Healthy Obese and Metabolically Obese but Normal Weight in Adults Worldwide: A Meta-Analysis. Horm. Metab. Res. 2015, 47, 839–845.

- Li, G.; Li, Y.; Han, L.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Q.; Xiao, X.; Qi, L.; Willi, S.M.; Li, M.; Mi, J.; et al. Interaction between early environment and genetic predisposition instigates the metabolically obese, normal weight phenotype in children: Findings from the BCAMS study. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 182, 393–403.

- Park, J.M.; Park, D.H.; Song, Y.; Kim, J.O.; Choi, J.E.; Kwon, Y.J.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, J.W.; Hong, K.W. Understanding the genetic architecture of the metabolically unhealthy normal weight and metabolically healthy obese phenotypes in a Korean population. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2279.

- Ruderman, N.; Chisholm, D.; Pi-Sunyer, X.; Schneider, S. The metabolically obese, normal-weight individual revisited. Diabetes 1998, 47, 699–713.