Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Communication

Energy tourism, which is quite recent despite the fact that the practice of tourists visiting power plants, very often for educational purposes, has a long tradition in Slovenia due to power plants on the Drava River. Particularly, the oldest Fala power plant is an area where the technical field of electric power production and transmission overlaps with tourism. Power facilities strongly influence the landscape, and that is why their inclusion into the tourist offer is worth considering.

- tourism

- storytelling

- Kobarid substation

- cooperation

- sustainability

- new media

1. Energy Tourism in Slovenia

In Slovenia, protected areas and natural heritage conservation concerns pose particular challenges for locating electric power facilities in the physical environment. The process must be pursued cautiously, responsibly and in consensus, following cultural heritage charters and documents [14], with thoughts focused on the environment and future development, which can also be linked to sustainable tourism. Numerous cases around the world indicate that electricity facilities, especially power stations, which signify a very pronounced encroachment on the environment, may also serve as an extraordinary opportunity to develop tourism, since the power stations may in themselves represent a tourist attraction and over the decades become part of the precious industrial heritage of a certain area. We may include in energy tourism numerous activities, for instance, touring wind farms and climbing the chimney stacks of thermal power stations, which is closely tied to adventure and sports tourism [15] and also tours of coal mines [16] and tours of farms and horticulture operations where food production is tied to energy [3,17]. There are also plenty of tourists who visit Slovenia and are interested in the hydropower stations along the River Drava—at Fala, the oldest hydropower station on the Drava, a museum has been set up. It is visited by more than 80 groups a year (more than 3000 visitors) that are led by a museum guide [18]. Tourists are also interested in the powerplants on the Sava or Soča, in the prospect of climbing the 360 m chimney stack at the Trbovlje thermal power station and, of course, the nuclear power plant in Krško. Up until the pandemic, the nuclear plant offered visits daily, in which it gave presentations of its operation. This involves strategic communication by nuclear power plants, whereby they seek to influence public opinion [19]. Each year, the nuclear plant has welcomed more than 5000 visitors, with more than half of them being students and secondary and primary school pupils, who visit the plant as part of their educational courses, while various companies, associations and professional groups have chosen the nuclear plant for technically themed excursions [10]. Some energy companies focus not just on experts and enthusiasts but also in particular on families with children and seniors [3]. Precisely because of the interest shown, the establishing of energy facilities as tourism products and the development of museums focused on electric power deserve even greater attention in relation to tourism. An example of a Slovenian electric energy museum is the Fala–Laško Museum of Electric Power Transmission [20], which is one of the rare museums in Europe to showcase such technical heritage. Since its opening in 2004, visitor numbers have consistently grown, despite the absence of intensive promotion, and since 2012, it has recorded more than 2000 visitors annually [21]. Electric energy facilities and objects that are entirely uninteresting for some tourists do in fact represent exceptional attractions for a certain segment of tourists. This is a type of niche tourism that Frantál and Urbánková [3] termed “energy tourism”, and it has the potential to draw tourists to what would be less attractive locations, thereby generating additional possibilities for employment, earnings and promotion [22]. In the Spanish Pyrenees, hydropower plants provided new impetus to the development of mountain tourism [23], and in Finland (the case of the Imatrankoski power plant, [24]) and Iceland, electric power facilities, especially hydropower plants and wind farms, which leave a distinct mark on the landscape, are of interest to tourists [25,26]. In Iceland, for instance, even in designing wind farms, they think about the wind turbines as tourist attractions and about including them as features of tourism [26], which is extremely important in terms of sustainability. The value and potential of electric power facilities for tourism has also been recognised in Austria and Germany [27], and partly in Italy and Croatia—looking at Slovenia’s neighbours. In Britain, the Drax power station in North Yorkshire was conducting up to six guided tours of the facility a day for tourists before the pandemic [28,29]. Such facilities have great potential, not just for visitor tours, but also for education, something noted by Mažeikienė [30] in the case of nuclear power plants, and which is of course an established practice in Slovenia, too, where by prior arrangement you can tour numerous power stations and learn about their operation and importance. Raising awareness about responsible electricity consumption is also a salient issue in terms of climate change and the target of the ‘below 2 degrees Celsius’ scenario, which is aligned with the strategic aims of the Paris Agreement and the sustainability goals of the UN (the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs 7, 8, 11, 13)) [31]. Of course, in the case of energy tourism, it involves for the most part visitors and tourists with special interests and naturally school children and pensioners. Equally, it should be noted with this type of tourism that some sections of the public and tourists will always oppose the construction of electricity infrastructure and the consequent encroachments on the physical environment, but in this regard, there is an interesting case precisely in Germany, where a study has shown that following initial opposition to environmental encroachments with electricity infrastructure, as much as 45% of German tourists affirmed that they realise there is electricity infrastructure at their destination, but only 4% said that this infrastructure bothered them [27].

Alongside power stations, transformer substations are also of interest to tourists. A positive case in Slovenia is the previously mentioned Fala–Laško Museum of Electric Power Transmission, where the first water-powered installation for generating electricity in Slovenia was constructed in 1885 (according to oral tradition, it was even earlier in 1881). The first electric light bulb in the Laško area and in Lower Styria was therefore lit up six years after Edison’s first creation of the light bulb. Electrification was possible through the construction of large generation facilities and the transmission of electric power over great distances, which came about in 1924, when the company Fala d. d. constructed a 77 km long, 80 kV transmission line from the Fala power station to the 80/35 kV transformer substation in Laško and then a 35 kV line from Laško substation to the Trbovlje thermal power station. In Slovenia and what was then Yugoslavia, this was the first long-distance transmission line. The first large-scale parallel operation was established, and the first maintenance shop was set up at the Laško substation. This marked the start of electricity transmission development in Slovenia [32].

Although this involves an entirely different type of electric power facility, the substations can also be included among museums and, for instance, among thematic tourist trails, and these can be furnished with informative digital content and information panels so that, through attractive content and stories, visitors and tourists can learn about their role and importance. The development of various thematic trails, which are offered to visitors and tourists with in-person guides or, more frequently, as independent tours using special applications, digital maps and brochures, is a popular tourist trend [33], which is in part because it requires no additional infrastructure and can be tied to all manner of content and existing products and services. In this way, such facilities are no longer just installations serving their original purpose, and for many people, an aesthetic blight on the landscape, but are their own kind of tourist attraction, helping to educate people about the importance of electricity infrastructure, technical heritage, the importance of engineering know-how for everyday life and progress. They also serve to raise awareness about sustainable development, environmental responsibility and linking the past with the future. All this can be achieved through collaboration with interested stakeholders in tourism and by designing (digital) content based primarily on stories, especially in case of Kobarid that has very rich natural and cultural heritage.

2. Storytelling in Energy Tourism

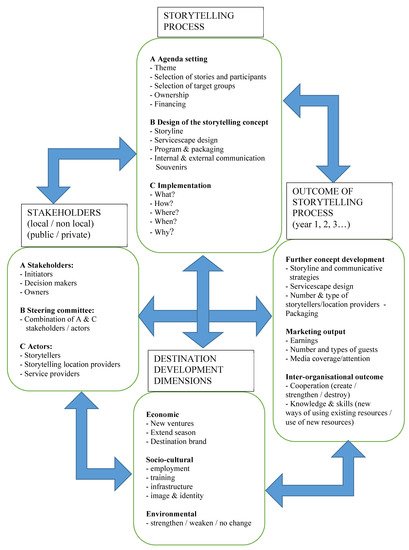

Stories have many roles, one of them being to explain and make some things or phenomena, such as research conclusions, climate change, technical issues, etc., possible to understand [34]. Since it was established that storytelling creates emotional connections between a destination and its target groups [33,35], products and destinations are branded through stories. Moreover, stories have the potential to solve complex challenges and facilitate collaboration [36]. By employing new technology and new media, stories—which are often characterized by high informational density [37]—may contribute successfully to the distinctiveness of a tourism product or a tourism destination. Digital technologies offer many possibilities for innovation in storytelling, including developing online museums of stories by employing various narrative techniques and travel writing [38]. This is significant because businesses and employees reliant on selling on the ground product or on receiving income from visitors depend on tourists’ engagement with the stories behind the products [39], and when it comes to applying storytelling in Tourism, it needs to be emphasised that “the storytelling concept requires communication between different stakeholders: Tourism policy makers, destination organisations and service providers. It includes tourism organisations, public administration at local and regional levels, private partners, different types of service providers (hotels, restaurants, museums, shops etc.) and storytellers (individuals)” [12] (p. 93). Successful storytelling, which can be a valuable tool for policymakers [36], includes experts from many fields. The storytelling model proposed by Mossberger et al. [12,40] represents the multi-way communication process of storytelling at a destination (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Mossberg’s storytelling model.

Yet, although science is aware of the necessary cooperation between the humanities, social sciences and natural sciences if changes such as energy efficiency and climate change are to be addressed successfully [41,42], in practice, there is still very little advice on how to complement narratives collected through qualitative research with technical knowledge from engineering [43]. One of the goals of this article is to show—with the case of the Kobarid substation—how technical knowledge may be used through storytelling in tourism and how interdisciplinary knowledge is employed for tourism purposes. As suggested by Gordon et al. [43], video storytelling could also be employed. In the videos and short video clips available online or via apps, experts involved in the project, in our case the project of the Kobarid substation, would explain the role of such infrastructure and the process of designing and building the facility, emphasizing the protection of nature and the protection of the autochthonous fish, marble trout (Salmo trutta marmoratus) [44]. This process of project design is explained later on in the article. Some authors [45] point out negative aspects of putting technology into unique tourism areas because of the possible negative effects on the landscape and wildlife, but environmental studies and the needs of the local community were in favour of the substation in Kobarid [46]. Another aspect that needs to be considered in the case of Kobarid is smart tourism destinations, where essential elements of smartness are infrastructure, human capital and information [47]. Thus, further developing tourist experiences should include creating intelligent platforms, applications [48] and ethnopôles—digital platforms presenting ethno-knowledge [49]. Of course, developing a smart storytelling model that involves all necessary stakeholders and data requires a careful study and planning but improves the tourist experience [48,50].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su14020659

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!