2. Mechanizmy biologiczne MONW

Based on the research carried out so far in the MONW group (women and men, in different age groups and different ethnic groups), it can be concluded that the excessive accumulation of fat, mainly visceral, adversely affects the lipid profile [

13,

14,

15], blood pressure [

13,

14], intensifies inflammatory and thrombotic processes [

16], as well as oxidative stress [

17]. On the other hand, in other studies in non-obese patients with an excessive accumulation of fat, no atherogenic lipid profile, differences in blood pressure values [

18,

19] or in the concentration of adipocytokines [

14,

15] were observed.

The central parts of the complex and still insufficiently recognized pathogenesis of MONW are the increased amount of visceral and subcutaneous fat in the abdominal area, insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, which are recognized as key disorders in MONW [

14,

19]. The increase in the mass of visceral adipose tissue causes increased lipolytic activity and the excess release of free fatty acids, which are accumulated in the liver and skeletal muscles. In the liver, increased very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) biosynthesis and reduced degradation, thereof, translate into an increase in the concentration of triglycerides in the blood plasma, and as a result of the action of lipoprotein lipase (LPL), cholesterol ester transfer protein (CEPT) and hepatic lipase (HL), LDL particles of high atherogenic potential are formed from VLDL particles. In addition, CETP-mediated multiplied lipid transport generates HDL particles of larger sizes. Hepatic insulin resistance is also manifested by increased glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, which increases endogenous glucose production and is associated with the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [

20]. On the other hand, in skeletal muscles, the accumulation of biologically active lipids (long-chain acyl-CoA, diacylglycerols, ceramides) negatively affects the operation of the insulin pathway, inducing muscle insulin resistance, which is associated with impaired translocation of GLUT4 to the cell membrane and reduced transport of glucose to the interior myocytes, thus preventing glucose uptake [

21]. This partially explains the complex relationships between obesity, insulin resistance, hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia.

Hypertrophic adipocytes are also a source of pro-inflammatory cytokines that enhance insulin resistance both in the fat cells themselves and in other tissues. Activated by inflammatory mediators (TNF-α, interleukin 1), nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathways are the link between chronic inflammation and insulin resistance [

22]. Obesity is accompanied by a subclinical chronic inflammation in which, in addition to activating pro-inflammatory signal transduction pathways, there is also an overexpression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in adipose tissue. Among the adipokines, whose activity may contribute to the development of metabolic disorders observed in MONW, the most frequently mentioned are resistin, leptin, adiponectin, TNF-α and IL-6 [

17,

23]. The pro-inflammatory and prothrombotic states are important components of the metabolic disorders associated with the excessive accumulation of adipose tissue, especially of the visceral type. The pro-inflammatory state is characterized by an increased concentration of cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6, as well as an increased concentration of acute phase proteins—fibrinogen and CRP protein. The prothrombotic state is diagnosed on the basis of elevated levels of fibrinogen, PAI-1 and other coagulation factors. Increased biosynthesis of the above-mentioned cytokines by lipid-laden adipocytes causes not only tissue resistance to insulin but also pro-inflammatory state, endothelial dysfunction and disorders of coagulation and fibrinolysis.

There is evidence from experimental and clinical studies for a causal relationship between the amount of body fat and insulin resistance and the development and maintenance of elevated blood pressure. The increase in the prevalence of arterial hypertension especially concerns visceral obesity [

24]. The etiological factors of arterial hypertension include: hemodynamic disorders accompanying obesity and an increase in peripheral vascular resistance associated with endothelial dysfunction, insulin resistance and the influence of adipokines released from adipose tissue [

25].

The excess of energy substrates flowing into the cell in the form of free fatty acids and glucose causes the formation of an increased amount of acetyl-CoA and, thus, NADP in the mitochondria and, as a result, an increase in the biosynthesis of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the development of oxidative stress [

26].

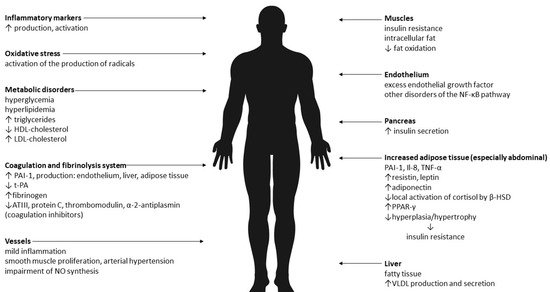

Therefore, it seems that the results of research on the pathogenesis of MONW to date are not unequivocal. The dominant causes are insulin resistance and abdominal obesity. It is believed that the cause of the changes is the increased mass of adipose tissue and its pro-inflammatory activity. Adipose tissue is an active endocrine and paracrine endocrine organ, and the secreted pro-inflammatory substances (adipokines) are an important link between excess body weight, insulin resistance, atherosclerosis and type 2 diabetes. In addition, there is oxidative stress. The effects of abdominal obesity and insulin resistance are summarized in Figure 1.

Rycina 1. Skutki otyłości brzusznej i insulinooporności [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26]. Legenda: VLDL—lipoproteina o bardzo małej gęstości, NO—tlenek azotu, PAI-1—inhibitor aktywatora plazminogenu-1, t-PA—tkankowy aktywator plazminogenu, ATIII—antytrombina III, NF-κB—Il-8—interleukina-8 , TNF-α – czynnik martwicy nowotworu α, β-HSD – dehydrogenaza beta-hydroksysteroidowa, PPAR-γ – receptor gamma aktywowany przez proliferatory peroksysomów, HDL – lipoproteina o dużej gęstości, LDL – lipoproteina o niskiej gęstości.

Wiadomo, że na występowanie MONW mają wpływ zarówno czynniki środowiskowe – brak aktywności fizycznej, niezdrowa dieta, palenie tytoniu, spożywanie alkoholu – jak i czynniki genetyczne. Podczas porównywania nawyków żywieniowych, kontrolowane badania wykazały, że kobiety z MONW spożywały więcej tłuszczów nasyconych i mniej błonnika niż kobiety zdrowe metabolicznie [ 27 ]. Efekt palenia potwierdzili Tilaki i Heidari [ 28 ]. Palenie było statystycznie istotnie ( p = 0,005) związane z fenotypem MONW u 170 mężczyzn i kobiet pochodzenia irańskiego. Badania w populacji koreańskiej wykazały, że istnieje związek między występowaniem MONW i umiarkowanym spożyciem alkoholu oraz niewielką ilością czasu na aktywność fizyczną o umiarkowanej intensywności [ 29].]. Palenie i spożywanie alkoholu jako czynniki ryzyka zostały potwierdzone w metaanalizie przeprowadzonej przez Wanga i in. [ 30 ]. Pewne jest, że na występowanie MONW mają również wpływ czynniki genetyczne. Jednak dane dotyczące konkretnych genów są dość ograniczone. Li i in. [ 31 ] wykazali, że CDKAL1 rs2206734 jest związany z ochroną przed fenotypem MONW. CDKAL1, należący do rodziny metylotiotransferaz, zwiększa wydajność translacji i jest szeroko eksprymowany w tkankach metabolicznych, w tym w tkance tłuszczowej i komórkach β trzustki. Z kolei Park i in. [ 32 ] znaleźli powiązania między genami GCKR, ABCB11, CDKAL1, CDKN2B, NT5C2 i APOC1 a zaburzeniami metabolicznymi u osób z prawidłową masą ciała.

3. Kryteria podstawowe dla MONW

Autorem pierwszych kryteriów diagnostycznych MONW jest Ruderman i in. [ 34 ], którzy w 1989 roku zaproponowali system punktacji oceniający 22 cechy ( tabela 1 ), którym przypisano określoną liczbę punktów. Uzyskanie co najmniej 7 punktów było równoznaczne z rozpoznaniem MONW.

Tabela 1. Skala punktowa do identyfikacji osób z MONW [ 34 ].

| Zwrotnica |

Objawy |

| 1 |

stężenie triglicerydów > 100–150 mg/dl

ciśnienie krwi 125–140/85–90 mmHg

przyrost masy ciała: >4 po 18 latach dla kobiet i 21 lat dla mężczyzn

BMI: 23–25 kg/m 2

talia: 71,1–76,2 dla kobiet i 86,3-91,4 dla mężczyzn

pochodzenie etniczne: czarne kobiety, Amerykanie pochodzenia japońskiego, Latynosi,

Melanezyjczycy, Polinezyjczycy, Maorysi z Nowej Zelandii |

| 2 |

nieprawidłowa glikemia na czczo (110–125 mg/dl)

stężenie triglicerydów > 150 mg/dl

ciśnienie krwi > 140/90 mmHg

samoistne nadciśnienie tętnicze (poniżej 60 lat)

przedwczesna choroba wieńcowa (poniżej 60 lat)

niska masa urodzeniowa (<2,5 kg) )

brak aktywności (<90 min ćwiczeń aerobowych/tydzień)

przyrost masy ciała: >8 po 18 latach dla kobiet i 21 lat dla mężczyzn

BMI: 25–27 kg/m 2

talia: >76,2 dla kobiet i >91,4 dla mężczyzn

kwas moczowy (> 8 mg/dl)

pochodzenie etniczne: Indianie, australijscy Aborygeni, Mikronezyjczycy, Naruanie |

| 3 |

cukrzyca ciążowa

stężenie triglicerydów > 150 mg/dl i HDL cholesterol < 35 mg/dl

cukrzyca typu 2 lub upośledzona tolerancja glukozy

hipertriglicerydemia

przyrost masy ciała: >12 po 18 latach u kobiet i 21 lat u mężczyzn

przedwczesna choroba wieńcowa serca (poniżej 60 lat )

pochodzenie etniczne: niektóre plemiona Indian amerykańskich |

| 4 |

cukrzyca typu 2

upośledzona tolerancja glukozy

policystyczne jajniki |

System ten miał swoje wady, wymagał wykonywania testów biochemicznych, które nie są rutynowo wykonywane u zdrowych ludzi (w tym badania stężenia kwasu moczowego). Z tego powodu rozpoczęto poszukiwania znacznie prostszych i bardziej dostępnych kryteriów diagnostycznych.