Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Oncology

This entry describes that the roles of alterations in 3D chromatin interactions.

- 3D genome

- breast cancer

- CTCF

1. The Interplay of Cis-Regulatory Elements Is Framed into a 3D Chromatin Structure

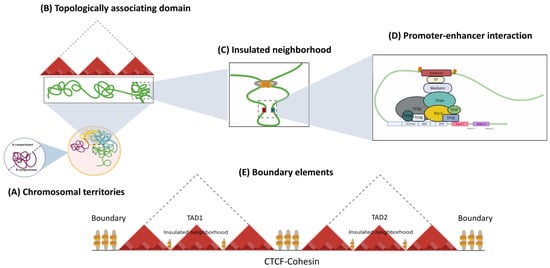

Genome function is a dynamic and flexible concept by nature, as each cell type requires the coordinated expression of genes that contribute to its fate and physiological properties. The three-dimensional organization of the genome is critical for cell identity, as it constantly evolves during adaptation to the environment [14,28,29]. Interphase nuclei show a complex and dynamic architecture of chromosomes and nuclear features. Chromosomes are structured inside the nuclear volume and occupy different regions, called chromosomal territories [30], which correspond to the highest level of hierarchical organization. Within Chromosome Territories (TCs), chromosomes are considered to be separated into two compartments. The A compartments comprise the internal regions of the nucleus, with genes that are usually actively transcribed, whereas the heterochromatic B compartments occupy the periphery of the nuclei and contain inactive genes [31]. Within a chromosomal territory, DNA loops are formed, which fold to build higher-order 3D structures known as topology-associated domains (TADs; see Figure 1) that are enriched and defined by insulator borders associated with CTCF [32]. Finally, inside each TAD, chromatin connections are fostered between a promoter region and enhancer, contributing to the shape transcription by limiting physical contact between regulatory elements [33,34].

Figure 1. Hierarchical organization of genome. The nucleus in mammalian cells is structured into chromosomes, which have a non-random distribution. (A) In interphase, each chromosome is located into discrete sub-nuclear domains called chromosomal territories (CT). Within interphase chromosomes, chromatin folds into (B) TADs, which are areas where frequent interactions occur between specific CREs and genes at the local level. (C) Insulated neighborhoods are loops constructed by CTCF/cohesin-bound anchors harboring genes and CREs that control gene expression. (D) The interaction between CTCF and cohesin facilitates the formation of chromatin loops, where Transcription factors (TF), such as pioneering TFs, bind to enhancers, allowing for the recruitment of the Mediator complex, which further assembles basic transcription machineries at the gene promoter and activates transcription. (E) The regions bordering TADs or TAD boundaries regulate gene expression by restricting interactions between adjacent CREs from distinct TADs, avoiding incorrect interactions.

Regarding the insulating elements, a study has identified that CTCF and the cohesin complex of structural proteins are the main players in the formation of chromatin loops. These proteins also contribute to the insulator function constraining the heterochromatin-associated position-effect variegation (PEV) phenomenon and mediate a large part of intra-chromosomal interactions [33,35,36]. CTCF-binding sites are enriched in the boundaries between TADs, as well as within intra-TAD chromatin loops (Figure 1) [34,37]. Cohesin, on the other hand, is a ring-shaped protein complex composed of SMC1A, SMC3, RAD21, and either SA1 or SA2 [38,39,40]. Evidence has suggested that the Mediator helps to initiate enhancer—promoter contact, followed by the recruitment of cohesin-loading proteins: the NIPBL/MAU2 complex [41,42]. CTCF and cohesin are thought to mediate TAD and loop formation by an extrusion model; in which, once cohesin is loaded into chromatin, its translocation forms a nascent loop until convergently oriented CTCF proteins are found [41,43]. The cohesin protein component SMC plays a key role in loop extrusion. SMC complexes form enormous rings that are believed to wrap DNA strands. The movement of the SMC ring through the DNA is due to motor activity controlled by one or both ATPase domains of the SMC protein sub-unit, which permits unfettered sliding throughout the DNA [41,44]. This results in a dynamic picture of loops that is constantly developing [45].

Mechanistically, CREs regulate their target genes by physically associating with their promoters through chromatin looping to form these long-range physical interactions. Although CTCF and cohesin have doubtlessly been shown to be essential for chromatin looping, other structural proteins are also involved (Figure 1). For example, the Mediator complex and Yin Yang 1 (YY1), which interact with cohesin and CTCF, respectively, have been proposed to mediate intrachromosomal contacts in interphase cells [14,46,47]. Nevertheless, evidence has suggested that the mechanism by which CREs find the appropriate gene target depends heavily on the TADs structure and CTCF boundaries.

2. A Disrupted Landscape of Topologically Associating Domains in Breast and Gynecological Malignancies

Transcriptional dysregulation of cancer-related genes and oncogenic non-coding RNA produces alterations in cell identity, indicating that the 3D chromatin architecture has a central function in governing gene transcription, cancer development, and cellular heterogeneity. In cancer cells, disruption of TAD structure or inter-TAD changes may cause chromatin rewiring, leading to the overexpression of oncogenes or down-regulation of tumor suppressors [48,49].

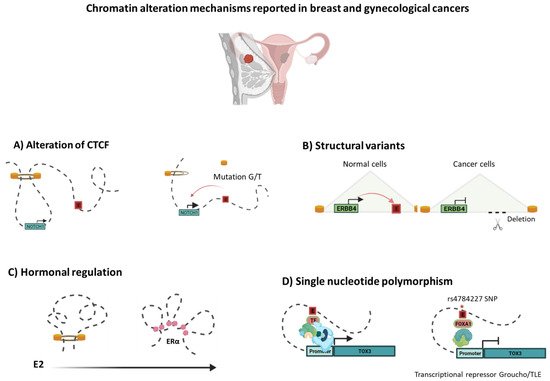

Structural TAD alterations or inter-TAD modifications occur in the cancer genome by different mechanisms, including alteration to CTCF (mutations, aberrant DNA methylation, or post-transcriptional modification) [43,50,51,52], cancer-risk single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), viral integration, hormonal response, and structural variants (SVs), such as deletions, insertions, inversions, duplications, or translocations [53,54].

3. CTCF Alterations Disrupt the 3D Structure of Chromatin

Breast and gynecological cancers, such as ovarian cancer, share common genetic and non-genetic risk factors including mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2, the most significant risk factors for both cancers, suggesting that similar biological mechanisms drive breast and ovarian cancer development. Mutations in the CTCF gene have been reported in breast cancer, endometrial cancer, and ovarian cancer [55,56]. These mutations are predominantly mis-sense or nonsense and, thus, have been predicted to impair CTCF function [55]. Some tumor cell mutations occur within the zinc fingers of CTCF and may selectively perturb certain loops, as they affect CTCF binding at only a subset of sites [57]. For example, in ovarian cancer, mutations in the CTCF motif anchors (G/T) at the boundary of the TAD motifs lead to NOTCH1 overexpression, most likely through inappropriate enhancer action caused by TAD disruption (Figure 2). Deregulation of the NOTCH signaling cascade has been linked to embryonic development, cell proliferation, and growth in many types of cancer [58].

Figure 2. Chromatin alteration mechanisms reported in breast and gynecological cancers. As proper chromatin structure folding is essential for gene regulation, disruption of the TAD structure or inter-TAD modifications may lead to rewiring of chromatin connections to activate certain oncogenes or down-regulation of tumor suppressors. Breast and gynecological cancer genomes have been reported as having diverse alterations, including: (A) Mutations in the CTCF motifs anchors (G/T) at the boundary of the TAD motifs, leading to NOTCH1 overexpression. (B) Alternatively, structural variants, such as deletions, in cancer genomes can frequently delete enhancers, contributing to oncogenesis by decreasing tumor suppressor gene expression (e.g., ERBB4) [53,54]. (C) Another mechanism that has been linked to dynamic changes in chromatin structure is hormonal response. Constant E2 stimulation promotes 3D genome re-compartmentalization by ERa binding, generating chromatin interactions of invasion-related oncogenes [59]. (D) Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) often exist in CREs, which may cause changes in interactions. The rs4784227 SNP alters the sequence of recognition of an enhancer that controls TOX3 gene transcription, favoring the binding of the FOXA1 transcription factor and Groucho/TLE, resulting in decreased expression of the TOX3 tumor suppressor gene [60].

Interestingly, viral integration can drive oncogenesis by chromatin reorganization. Mehran et al. have shown that the viral integration of human papillomavirus (HPV) introduces new CTCF binding sites in the cervical cancer genome.

This promotes local changes in the expression of genes related to tumor viability, such as FOXA, KLF12, SOX2, CUL2, CD274, and PBX1, and the viral oncogenes E6 and E7 that mediate mitogenic and anti-apoptotic stimuli, by interacting with numerous regulatory proteins of the host cell that control the cell cycle in some HPV+ tumors [61].

In cancer cells, CTCF can also undergo a number of post-translational modifications which change its properties and functions. One such modification which has been linked to cancer is poly (ADP)-ribosylation (PARylation) at the n-terminal domains of CTCF, which promote the insulator and transcription factor functions of CTCF, while phosphorylation impairs its DNA binding activity [62]. CTCF phosphorylation at threonine (T) 374 and serine (S) 402 has been observed in breast cancer [63]. The Hippo-LATS signaling pathway is a key regulator of cell proliferation, apoptosis, tissue homeostasis, and tumorigenesis. LATS1/2 kinases are the key players in this cascade, which phosphorylate the YAP protein and cause its sequestration in the cytoplasm, resulting in cell apoptosis and growth arrest. In breast cancer, YAP is overexpressed and functions as a transcriptional coactivator for a group of genes that facilitate cell growth and survival. In MCF7 cells, it has recently been discovered that LATS kinases phosphorylate CTCF at one of its zinc fingers, impairing its DNA binding and canceling the chromatin looping of YAP target genes (AMOTL2, AXL, CRY1, GLI2), suggesting that CTCF-mediated insulated neighborhoods could be necessary for YAP target gene activation [63].

Finally, the aberrant transcriptional silencing of tumor suppressor genes is accompanied by dynamic changes in chromatin structure mediated by CTCF. For instance, CTCF plays a role in establishing and maintaining the tumor suppressor p16 in higher-order chromosomal domains through appropriate boundary formation. p16 is a key regulator of cell cycle arrest in G1 and senescence, primarily through inhibition of the cyclin-dependent kinases CDK4 and CDK6. In fact, inactivation of the p16 gene by promoter methylation is one of the earliest losses of tumor suppressor function in numerous types of human cancers, including breast cancer. In p16-expressing MDA-MB-435 breast-cancer cells, CTCF binds downstream of the region enriched for heterochromatin marks located within −2 kb and +1 kb of the active promoter of the p16 gene; however, in T47D breast cancer cells that contain aberrantly silenced p16, the boundary domain at −2 kb disappears and prevents CTCF binding, hereby promoting the spread of heterochromatin marks throughout the entire p16 promoter region. These data raise the possibility that the dissociation of CTCF from p16 during early tumorigenesis is not due to DNA methylation alone but may result from loss of function of CTCF to organize a boundary or insulator element. This, in turn, would result in secondary changes in chromatin structure that are incompatible with CTCF binding to DNA [64].

4. Hormones Drive Dynamic Transitions in Chromatin Architecture Which Influence Gene Expression

Hormones, which are known to have strong effects on gene function, may induce dynamic changes in chromatin organization. In the 3D genome, estrogen therapy has been shown to induce enhancer-promoter interactions through chromatin looping structures around target genes, including the keratin gene cluster, NR2F2, and SIAH2, as well as organizing the suppression of genes down-regulated in breast cancer basal-like sub-types, such as TAOK2 [65,66]. Surprisingly, TADs function as units of steroid hormone response. Some TADs contain binding sequences for the estrogen receptor (ESR1) and progesterone receptor (PGR), which are referred to as hormone-control areas (HCRs). In T47D cells, Dily et al. discovered over 200 HCRs with ESR1 and PGR binding sites that form a looping pattern, allowing intra-TAD interactions and enhancing the transcriptional activity of genes located in TADs with HCRs.

One of these TADs, for example, includes the ESR1 gene as well as five other protein-coding genes, including ZBTB2, RMND1, ARMT1, CCDC170, and SYNE1, all of which are coordinately controlled by estradiol (E2) and progestins (Pg). In the absence of hormones, ESR1-TAD maintains a basal expression of resident genes. In comparison, when exposed to Pg and E2, ESR1-TAD is restructured to create intra-TAD interactions and appears to increase transcriptional activity [67]. Similarly, E2 and the synthetic progestin R5020 have been shown to promote the binding of PR and the transcriptional factor Paired box gene 2 (PAX2) in Ishikawa endometrial cancer cells, resulting in enhancer-promoter interacting loops within a TAD with HCRs, which contains several tumor development genes such as HMGA2, ETV4, ETV7, and GZMB [68].

Additionally, Zhou et al. have demonstrated a complex 3D chromatin structure over a time course of E2 stimulation in breast cancer cells MCF7 and T47D. Constitutive estrogen stimulation increased ERa binding but decreased CTCF binding. ERa promoted the re-compartmentalization of interactions in TADs enriched with genes related to invasion, aggressiveness, or metabolism signaling pathways; ECM receptor interaction; focal adhesion; and the cell cycle (Figure 3) [59].

5. Cancer-Risk Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms Promote Pathogenic Promoter-Enhancer Interactions

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) often exist in CREs, which may result in pathogenic promoter—enhancer interactions and, therefore, aberrant gene expression, according to genome-wide association studies (GWAS). SNPs in CREs may alter the DNA recognition motifs of TFs. These alterations cause them to interact with other elements differently, influencing changes in intra-TAD interactions and gene expression [49]. Indeed, the variant risk allele of the rs4784227 SNP alters the sequence of a Forkhead DNA recognition motif inside an enhancer that controls TOX3 gene expression, favoring the binding of the FOXA1 (Figure 2). The increased binding of FOXA1 represses the enhancer’s transactivation capacity through recruitment of the transcriptional repressor Groucho/TLE, resulting in decreased expression of the TOX3 tumor suppressor gene, providing additional proof of genetic alterations targeting enhancers in cancer [60].

In endometrial cancer, Painter et al. have described a putative regulatory element that interacts with AKT1—a member of the PI3K/AKT/MTOR intracellular signaling pathway—and negatively affects AKT1 expression. Association and functional analyses have demonstrated that the SNP rs2494737 maps to this silencer element, affecting its regulatory capability over the AKT1 promoter, hence resulting in increased AKT1 expression in both Ishikawa and EN-1078D endometrial cancer cells [86]. Cyclin D1 is one of the most significant cell cycle regulators. It is a member of the D-type cyclin family, which regulates cell cycle progression from G1 to S phase by modulating the function of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs). In addition, CCND1 is also a well-known oncogene that plays a key role in cell cycle progression and whose overexpression in breast cancer has been linked to poor prognosis. The CCND1 promoter is located 125 kb downstream of a putative regulatory element 1 (PRE1 enhancer), and regularly interacts in ER+ MCF7 and T47D cells. Surprisingly, breast cancer SNPs (rs78540526 and rs554219) in PRE1 almost completely abolished enhancer function and decreased the amount of cyclin D1 protein in MCF7 cells [87]. This evidence demonstrates that disease-linked regulatory SNPs can impact chromatin 3D interactions between genes and regulatory elements to modulate target gene expression.

A recent GWAS study revealed that the SNPs rs1011970 and rs615552 increase the risk of breast and gynecological malignancies in a region on chromosome 9p21 [88,89].

9p21 comprises three genes: CDKN2B (encoding p15ink4b), CDKN2A (encoding p16INK4a and p14ARF), and the 3′ end of CDKN2BAS (an anti-sense non-coding RNA in the INK4 locus; ANRIL) [90]. Farooq et al. have previously found an enhancer cluster adjacent to the INK4a gene with 24 core enhancers (E1–E24) in HPV-positive cervical tumors. This enhancer cluster is closely linked to the transcriptional activation of CDKN2A, which physically interacts with five enhancers, according to a chromosomal conformation capture approach (4C): E5, E8, E12, E17, and E19. Individual deletion of the three interacting enhancers (E8, E12, and E17) suppressed INK4a, ARF, and INK4b promoter transcription, and HPV-positive cell proliferation and migration were hampered when a single enhancer is deleted [91].

6. Chromatin 3D Alterations: miRNAs and lncRNAs Landscapes

CREs also play a direct role in non-coding RNA (ncRNA) expression regulation, through long-range chromatin interactions. Genes encoding microRNAs (miRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are transcriptionally regulated in a way similar to protein-coding genes. The first confirmation of this emerged from early biological experiments, which showed many cases of miRNAs and lncRNAs being transcribed by RNAPII [92,93]. Additionally, there is evidence that a set of RNAPII-associated transcription factors, such as c-Myc, cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB), SP1, p53, and MyoD [94,95,96], regulate miRNA and lncRNA expression. Notably, for some ncRNAs associated with cancer, 3D chromatin interactions could be rewritten, leading to enhancer—miRNAs- or enhancer—lncRNAs-altered interactions promoting changes in ncRNA expression [97].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cells11010075

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!