Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Developmental Biology

|

Neurosciences

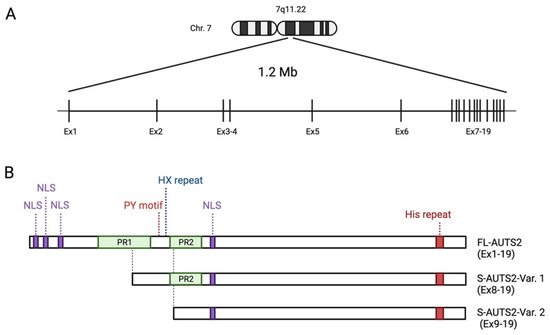

AUTS2 is a large gene spanning 1.2 M bases on human chromosome 7q11.22 (A). It consists of 19 exons, the first 6 of which are separated by long introns at the 5′ end, whilst the remaining 13 are compact with clustered smaller introns at the 3′ end. The full-lengthAUTS2transcript encodes a protein with 1259 amino acids (aa) in humans (NM_015570) and 1261 aa in mice (NM_177047), although various isoforms are generated by alternative splicing and multiple transcription start sites (TSS).

- autism susceptibility candidate 2 (AUTS2)

- autism spectrum disorders (ASD)

- epigenetic modulation

- cytoskeleton

- neurogenesis

- neuronal migration

- neuritogenesis

- synapse

- cerebellum

1. Structure and Expression of the AUTS2 Gene

AUTS2 is a large gene spanning 1.2 M bases on human chromosome 7q11.22 (Figure 1A) [12,23]. It consists of 19 exons, the first 6 of which are separated by long introns at the 5′ end, whilst the remaining 13 are compact with clustered smaller introns at the 3′ end. The full-length AUTS2 transcript encodes a protein with 1259 amino acids (aa) in humans (NM_015570) and 1261 aa in mice (NM_177047), although various isoforms are generated by alternative splicing and multiple transcription start sites (TSS). In the human brain, a short 3′ AUTS2 transcript generated from TSS within exon 9 has been identified by 5′ RACE (5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends) [14]. In the developing mouse brain, two short C-terminal AUTS2 isoforms translated from exon 8 (S-AUTS2-Var1; ~88 kDa) and exon 9 (S-AUTS2-Var2; ~78 kDa), as well as the full-length AUTS2 (FL-AUTS2; ~170 kDa) were detected by 5′ RACE and immunoblot experiments [24,25]. Additional alternative splicing AUTS2 variants skipping exons 10 and 12 in humans (corresponding to exons 11 and 13 in mice) were also found in the fetal brain [26].

Figure 1. Schematic showing the human AUTS2 gene genomic region and the structure of AUTS2 protein isoforms: (A) Genomic structure of human AUTS2 locus on chromosome 7q11.2 (Chr. 7), consisting of 19 exons (Ex). (B) Schematic representation of the protein structure of full-length and C-terminal short AUTS2 isoforms. The location of predicted domains, motifs, and other characteristic sequences are shown. NLS: nuclear localization signal sequence; PR: proline-rich domains. Illustration created with BioRender.com.

In the mouse cerebral cortex, FL-AUTS2 and S-AUTS2-Var1 appear from the early embryonic stages [24,27]. The long isoform shows the highest expression level at later embryonic stages around embryonic days 16–18, and is also present postnatally; although, it gradually decreases thereafter. In contrast, the short isoform is transiently expressed in embryonic brains and disappear postnatally. Interestingly, in mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs), an isoform switch from the long to short AUTS2 isoform occurs during the transition from undifferentiated to differentiated cortical neuronal states [26].

In the normal mouse brain, S-AUTS2-Var2 is barely detectable compared to other AUTS2 isoforms. In contrast, the expression of this shortest isoform was abnormally increased in mutant mice lacking exon 8 of Auts2 [24,25]. These findings suggest that there are internal enhancer/promoter regions for the alternative transcription of S-AUTS2, tightly regulating the temporal expression pattern of AUTS2 isoforms in the brain. Several potential enhancer regions have been identified within the introns of this gene in zebrafish and mice [12]. Furthermore, Kondrychyn et al. demonstrated that the AUTS2 ortholog in zebrafish, auts2, potentially has 13 unique TSSs, and more than 20 alternative transcripts were found to be produced from this gene locus [28]. Therefore, the complexity of this gene may be substantially higher in mammals as compared to other species than previously identified. In humans, some of the genomic variants were identified within intronic regions of the AUTS2 locus in patients with NDDs, implying that disorganized expression of AUTS2 may be associated with the onset of these disorders [21]. Auts2 expression is reportedly regulated by T-box brain protein 1 (Tbr1), a transcription involved in the development of cortical deep-layer projection neurons and also implicated in ASD [29,30]. In addition, methyl CpG binding protein 2 (MECP2), whose gene mutations are associated with Rett syndrome and ASD, suppresses AUTS2 expression [31,32].

Auts2 is widely expressed in multiple regions of the developing mouse brain, but particularly strong levels are observed within areas related to higher cognitive functions, such as the cerebral cortex, the Ammon’s horn and dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, and the cerebellum [33]. In postnatal and fully developed mouse brains, Auts2 expression is restricted to a few types of neurons, but is strong in glutamatergic projection neurons in the prefrontal cortex, pyramidal CA neurons in the hippocampus, granule neurons of the dentate gyrus, and cerebellar Purkinje and Golgi cells [33,34].

2. Genotype–Phenotype Correlations of AUTS2 Syndrome

As noted, a wide range of neurodevelopmental phenotypes in the patients with AUTS2 syndrome have been reported in individual studies; however, few studies have systematically reviewed the relationship between genotype and phenotype using a relatively large cohort of patients with AUTS2 mutations. In 2013, Beunders et al. collected the clinical data of patients (17 individuals and 4 family members) carrying exonic AUTS2 deletions from a large cohort (49,684 samples) with ID and/or multiple congenital anomalies, and examined the genotype–phenotype correlations in AUTS2 syndrome [14]. In that study, they originally established an AUTS2 syndrome severity score (ASSS) system, which was based on the sum of 32 clinical features observed with a frequency of over 10% in the first cohort of individuals with AUTS2 mutations. The ASSS system includes physical (growth, feeding, dysmorphic features, and skeletal disorders) and neuropsychiatric (neurological and neurodevelopmental disorders) phenotypes and congenital anomalies. Their paradigm revealed that the patients with deletions of the conserved C-terminal regions of AUTS2 (exons at the 3′ of the AUTS2 gene) showed severe AUTS2 syndrome phenotypes including neurodevelopmental disorders and dysmorphic features. In contrast, the individuals with small in-frame deletions of the different combinations of exons 2–5 at a non-conserved 5′ region (N-terminus of AUTS2) displayed lower ASSS values and milder pathological features [14].

After the initial description by Beunders et al., a meta-analysis using the data of 31 patients with AUTS2 syndrome obtained from seven studies, in addition to five newly identified clinical cases, supported that the patients with ADHD and/or ASDs, who carry mutations at 3′ end of the AUTS2 locus showed higher ASSS values compared with individuals with AUTS2 aberrations at the 5′ end of the locus [35]. These findings imply that the ablation of C-terminal region of AUTS2 may contribute to the onset of AUTS2 syndrome. Meanwhile, the individuals carrying a frame shift microdeletion within exon 6 or 7, which would only disrupt full-length AUTS2 transcript but were unlikely to affect the C-terminal AUTS2 short transcripts [36], have reportedly exhibited severe AUTS2 syndrome phenotypes. Taken together, this evidence implies that the deletion of the C-terminal region of full-length AUTS2 transcript and/or the loss of expression of C-terminal AUTS2 short transcripts may contribute to the onset of AUTS2 syndrome.

3. Protein Structure of AUTS2

Protein primary structure analysis predicts that AUTS2 possesses several putative nuclear localization signal sequences and two proline-rich domains (PR1 and PR2) (Figure 1B) [11,21]. Other predicted protein motifs include a PY (Pro-Tyr) motif (PPPY), eight CAG (His) repeats, several protein kinase phosphorylation sites, and putative SH2- and SH3-binding domains; however, the exact role of these motifs has not been well analyzed. The PY motif could act as a binding motif to a WW domain that is present in the activation domain of several transcription factors [37]. The His repeat is found in some nuclear proteins, which have been reported to function in the targeting of proteins to subnuclear compartments, such as nuclear speckles [38]. AUTS2 is also predicted to contain several conserved domains that may be involved in RNA metabolism. Castanza et al. found that AUTS2 binds to RNA transcripts related to various biological processes [39]. Proteomic analyses identified several RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) as the AUTS2-binding molecules in the mouse neonatal cerebral cortex, such as RNA splicing factors (splicing factor proline-glutamine rich (SFPQ), serine-rich splicing factor 3 (SRSF3)), the RNA helicases (DDX5 and 17), and the RBP, NONO [39]. Although the physiological significance of the interaction of AUTS2 with RNAs or RBPs remains to be clarified, it is conceivable that AUTS2 may control protein expression through RNA metabolism in addition to transcriptional regulation, as described below.

AUTS2 has an additional characteristic histidine-rich sequence (HX repeats) between the PR domains. Individuals carrying de novo in-frame microdeletion within the region corresponding to HX repeats in the AUTS2 locus display NDDs, including cognitive delay, microcephaly, and craniofacial dysmorphisms [40,41]. Liu et al. recently found that AUTS2 interacts with a histone acetyltransferase P300/CBP via its HX repeats motif, which is required for the differentiation of neural progenitor cells into neurons [41].

4. Cytoplasmic AUTS2 Functions in Cytoskeletal Organization

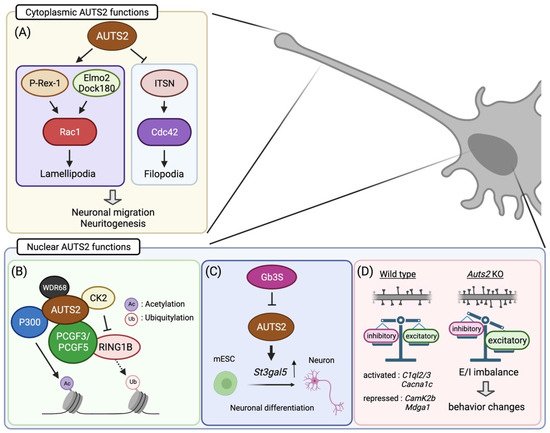

AUTS2 is found in the cell nuclei of glutamatergic neurons in the mouse cerebral cortex during early developmental stages [24]. As neural development proceeds, it also appears in the cytoplasm of differentiated neurons, including dendrites, axons, and cell bodies. Subcellular localization analyses showed that FL-AUTS2 was localized in both the nucleus and cytoplasm, whereas the S-AUTS2 isoforms were exclusively nuclear [24]. Cytoplasmic AUTS2 is involved in cell motility and morphogenesis by regulating reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton (Figure 2A) [24]. AUTS2 activates the Rho-family small GTPase Rac1 via guanine exchange factors (GEFs), such as P-Rex1 or the Elmo2/Dock180 complex, leading to lamellipodia formation in neuroblastoma cell lines. In contrast, AUTS2 inhibits filopodia formation by suppressing the activities of another Rho-family G protein, Cdc42, through interaction with its GEF, intersectin 1 and 2.

Figure 2. Summary of the molecular and cellular functions of AUTS2 in neurodevelopment: (A) Cytoplasmic AUTS2 activates the Rac1 signaling pathway via P-Rex1 and Elmo2/Dock180 complex, promoting neuronal migration and neurite extension. In contrast, AUTS2 inhibits Cdc42 activities to suppress filopodia formation. (B–D) In cell nuclei, AUTS2 activates gene transcription through histone modification by interacting with the PRC1 complex (B). AUTS2 represses the monoubiquitylation activity of RING1B by recruiting CK2 while promoting histone acetylation via P300. (C) AUTS2 controls neuronal differentiation from mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) through transcriptional activation of the sphingolipid-producing enzyme gene, St3gal5. In mESC, AUTS2 expression is repressed by globo-series glycosphingolipids generated from Gb3 synthase, Gb3S. (D) AUTS2 modulates the E/I balance by limiting the number of excitatory synapses. Loss of Auts2 leads to increased dendritic spine formation, disturbing the E/I balance within neural circuits. AUTS2 regulates the expression of the gene related to synapse development and functions. Moreover, Auts2 mutant mice display behavioral abnormalities in social interaction, vocal communication, cognition, and motor skills. Illustration created with BioRender.com.

5. Transcriptional Regulation by Nuclear AUTS2

Nuclear AUTS2 functions as a regulator of gene transcription during neurodevelopment. Genomic profiling of AUTS2 by chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing, in combination with transcriptome analysis (RNA sequencing), revealed that it interacts with the promoter and enhancer regions of the genes related to brain development as well as those associated with NDDs, many of which are actively expressed in the developing mouse forebrain [42]. In addition, AUTS2 shares DNA-binding motifs with some transcription factors that are involved in neural development, including TCF3, Pitx3, and FOXO3, implying that AUTS2 functions in transcriptional activation [42]. Gao et al. found that AUTS2 interacts with an epigenetic regulator type I Polycomb repressive complex (PRC) 1 (Figure 2B) [27]. PRC1 canonically functions as a transcriptional repressor to maintain gene silencing through the compaction of local chromatin by depositing monoubiquitylation of histone H2A at lysine-119 (H2AK119ub1) via its core component RING1A/B [43]. Incorporation of AUTS2 into the PRC1 complex converts this complex to a transcriptional activator by recruiting two other components, casein kinase 2 (CK2), and histone acetyltransferase P300/CBP [27]. CK2 inhibits the monoubiquitylation activity of RING1 proteins, while P300 promotes transcription by acetylating histone H3 at lysine-27 (H3K27ac). In mESCs, the WD40-repeats-containing protein WDR68 mediates transcriptional activation by induction of the AUTS2-PRC1 complex [44]. On the other hand, Monderer-Rothkoff et al. demonstrated that in the luciferase reporter assay, while both FL-AUTS2 and S-AUTS2 activated gene transcription in non-neuronal HEK293 cells, FL-AUTS2 or N-terminal AUTS2 fragment (encoded by exons 1–9) can function as transcriptional repressors in neuroblastoma Neuro2A cells [26]. Whether AUTS2 acts as a transcriptional activator or repressor may therefore depend on the intracellular context, that is, which AUTS2-binding co-factor(s) are expressed.

6. The Role of AUTS2 in Neurogenesis

Since the first report by Sultana et al. in 2002, a number of clinical genomic analyses have demonstrated the association of AUTS2 mutations with NDDs, albeit the molecular and biological functions of this gene have long remained unknown. In 2013, two different groups attempted to determine the function of AUTS2 by means of knockdown experiments using morpholino in a zebrafish model [12,14]. The auts2 morphants displayed developmental abnormalities, including microcephaly and craniofacial dysmorphisms (smaller jaw size). In the morphant brains, neuronal cells were markedly decreased in various regions, such as the cerebellum, optic tectum, and retina, which was likely based on an increase in apoptosis and/or a decrease in neuronal differentiation [12,14]. Co-introduction of full-length human AUTS2 mRNA together with the auts2 morpholino restored morphant phenotypes back to normal. Moreover, the 3′-end short transcript corresponding to a human AUTS2 short isoform could also rescue the phenotype, suggesting that the C-terminal region of AUTS2 contains the domains crucially involved in neural development. This is likely correlated with the observation that the severity of the symptoms of AUTS2 syndrome is prominent in individuals with disruption at the 3′ end of the AUTS2 locus [14]. Mice lacking Auts2 exhibit hypoplasia in the dentate gyrus as well as in the cerebellum [34,39,45]. These findings suggest that AUTS2 plays a key role in neural development in the brain.

In addition, the in vitro analyses using mESCs demonstrated that AUTS2 is involved in neuronal differentiation through histone modifications together with the aforementioned PRC1 complex, including P300, CK2, and WDR68 [41,44,46]. Similar to the findings in the zebrafish model, disrupting the Auts2 gene in mESC led to increased cell death during differentiation into neurons, which was rescued by expressing the C-terminal AUTS2 shot isoform as well as FL-AUTS2 [26]. Meanwhile, forced expression of FL-AUTS2 in mESCs leads to the delay of neuronal differentiation [34]. Furthermore, Russo et al. found that AUTS2 promotes neuronal differentiation through transcriptional activation of the sphingolipid-modifying enzyme GM3S (Figure 2C) [46]. Taken together, these findings suggest that AUT2 controls neuronal differentiation by transcriptional regulation via histone modification, an epigenetic mechanism.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cells11010011

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!