Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Nutrition & Dietetics

A new type of foods with function claims, called Foods with Function Claims (FFC) in Japan, was introduced in April 2015. The FFC allows manufactures to submit labeling to the Secretary-General of the Consumer Affairs Agency in Japan that indicates the food is expected to have a specific effect on health.

- clinical trial registration

- protocol

- compliance

1. Introduction

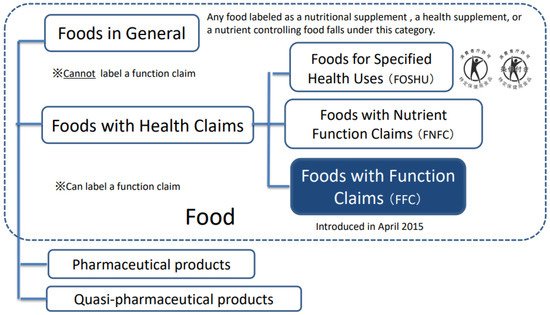

The Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC) is an intergovernmental organization that was founded in 1962 by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) [1]. The basic principles of CAC are that health claims should be substantiated by currently sound and sufficient scientific evidence, provide truthful and non-misleading information that consumers can use to choose healthy diets, and be supported by specific consumer education [2]. In accordance with CAC guidelines, only government-permitted Foods for Specified Health Uses (FOSHU) and foods with nutrient function claims (FNFC) can make function claims on food labels in Japan, and these must comply with specifications and standards designated by the government [3]. The FNFC can be used to supplement or complement the daily requirement of nutrients (vitamins, minerals, etc.) that tend to be insufficient in an everyday diet. The FOSHU are scientifically accepted for their usefulness in maintaining and promoting health and are therefore permitted to contain food effects and safety claims that have been evaluated by the government.

In addition to these categories, a new type of foods with health claims, called Foods with Function Claims (FFC), was introduced in April 2015 (Figure 1). The FFC allows manufacturers to submit labeling to the Secretary-General of the Consumer Affairs Agency (CAA) in Japan that indicates the food is expected to have a specific effect on health. Unlike the strict evaluation criteria applied through the FOSHU and FNFC processes, the FFC is only a notification system in which food manufacturers must meet five specific criteria. Although the government does not evaluate the safety and effectiveness of the submitted product, i.e., it does not utilize a notification system, the industry (applicant) must fulfill several procedures to submit a notification. All the FFC criteria submitted by the manufacturers are disclosed on the CCA website, which gives approval for the labeling of food products. For a food product to claim effectiveness on its label, evidence for its proposed function claims must be substantiated by one of two standard scientific methods: clinical trials (CTs) such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or systematic reviews (SRs). Detailed guidelines about the use of these two methods for the FFC have been published on the CAA website [4].

Figure 1. Food labeled with certain nutritional or health functions in Japan (modified partially for this study based on the Consumer Affairs Agency website in Japan). The new system (FFC) allows labeling, which indicates that the food is expected to have a specific effect on health, except for reducing the risk of diseases, through the process of submission to the Secretary-General of the Consumer Affairs Agency in Japan.

The problem with the FFC notification system, which is the adequacy of research reports, has been highlighted by the CAA and by research groups. The CAA examined 50 reported CTs and determined that many had inappropriate protocols and methods for evaluating the risk of bias and also had conflicts of interest [5]. Tanemura et al. identified problems with the reporting quality and associated issues for RCTs of the FFC [6]. There was insufficient information on items associated with sample size, allocation and blinding, results of outcomes and estimation, generalizability of the results, and study registration numbers. To protect consumers, these reports suggested that researchers should monitor and confirm that referenced RCTs are above a certain level of quality.

Helsinki Declaration (2013) declared that “Every research study involving human subjects must be registered in a publicly accessible database before recruitment of the first subject” [7]. Clinical trial registration (CTR) of CTs is extremely important for promoting transparency and integrity in medical research and helps to ensure a complete and non-biased record of all CTs [8,9,10,11]. Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) require CTR of CTs in all medical journals [12].

2. Discussion

2.1. Registration of Protocol

Despite the widespread endorsement of CTR globally, CTR in FFC remains suboptimal, with no registration or, in many cases, unknown existence of the protocol itself (24%). Our findings are consistent with previous studies that reported protocols were not fully registered [16,17,18,19,20,21]. Gopal et al. [18] concluded that unregistered trials were more likely to report favorable findings than were registered trials (89% vs. 64%, relative risk = 1.38, 95% confidence interval = 1.20–1.58; p = 0.004). No registration or absence of the protocol immediately creates doubt about the internal validity of results in a CT. Therefore, the validity of target articles in this study is unknown, especially if there were protocol violations [22], which could lead to flawed conclusions based on systematic errors and/or protocol deviations [23].

There are also few registrations in the fields of surgery [19] and addiction [20] or for trials in a single country’s health research [21], which could be because the journal’s regulation did not require registration as a prerequisite for submitting papers. The same might be inferred in the field of nutrition, so journals other than ICMJE member journals are also considered to have an urgent need to register protocols. The CTR was specified in the CONSORT 2010 statement [24,25] and the CONSORT 2010 statement: crossover extension [26], which describe the method for RCT reporting, and in SPIRIT 2013 [27], which summarizes the reports of CT protocols. In spite of the existence of these early guidelines, the oldest of the target articles in our study was published in 2015, and there were many relatively newer reports, which suggests that the importance of registration is not yet well understood by journals and researchers.

The FFC guideline stated that “research started within one year after the enforcement of the FFC system may be reported in a format that does not comply with international guidelines”. This special measure may have led to a disregard for the importance of the protocol [4]. In the case of industry funding, there is evidence that favorable results are more likely to be reported and that unfavorable results are difficult to report [28]. Almost all FFC notifications were from industries, and 80% of the authors of the target papers were affiliated with those industries, so this problem is worrisome.

2.2. Inconsistency with Protocol

There were discrepancies between registered and published primary outcomes (about 30%), which indicated there might be selective outcome reporting that has been previously described [8,10,13,14,15]. Neither compliance items T nor I contained detailed information on the test food in a quarter of the protocols. We could not even identify what the study was. This concealment must have been to prevent other competitors from stealing the intended food development content. In the author category, academia is not directly related to business, and this may be supported by the fact that academia had a significantly higher quality score than non-profit. In corporations, there are usually “trade secrets”, especially for new products. When researchers employed by the company conduct a CT, they may conceal the registration of contents because they recognize that the functional component of the product is confidential. In such cases, it is meaningless that CTR exists because it is unclear what kind of research was conducted. To remedy this situation, researchers need to re-familiarize themselves with the four dimensions of the purpose of the ICMJE registration policy [12].

2.3. Impact on SRs

For a food product to claim effectiveness on the FFC’s label, evidence for its proposed function claims must be substantiated by another standard scientific method, specifically SRs. In fact, under the FFC system, about 90% of notifications are from SRs [4]. Previous studies [29,30] that evaluated the quality of methodologies and reporting in SRs based on the FFC reported that there were very poor descriptions and/or implementation of study selection, data extraction, search strategy, evaluation methodology for risk of bias, assessment of publication bias, and formulating conclusions based on methodological rigor and scientific quality of the included studies.

Furthermore, when SRs contain RCTs with inappropriate and biased protocols, such as those included in this study, the reliability of the FFC’s claim may be questionable. While SRs exceeding the number of RCTs have been published globally [31], high-quality CTs are required, and registration of the protocol is most essential.

2.4. Future Research Challenges to Improve the Compliance of Protocols on the FFC

Table 3 summarizes the future challenges for CTs on the health enhancement effects of the FFC and related healthy foods. Regarding the food industry and for-profit researchers, they should reconfirm Helsinki Declaration and ICMJE policy and study the current standard guidelines for RCTs (i.e., CONSORT 2010 statement [24,25], CONSORT 2010 statement-crossover extension [26], and SPIRIT 2013 [27]) before research is conducted. In fact, in Japan, all of these guidelines have been translated into Japanese [32,33,34] and published for use by researchers who are unfamiliar with English. Academia researchers at Japanese universities and national research institutes regularly take research ethics education programs to prevent research misconduct. Such education, while not essential for industry, transcends economic objectives and may be necessary to improve protocol compliance.

Table 3. Future challenges to improve protocol compliance in the food-related clinical trials.

| For food industry and researcher | |

| #1 | Researchers should be based on Helsinki Declaration and ICMJE policy. |

| #2 | Researchers should be based on some reporting guidelines: CONSORT 2010 and its extension, and SPIRIT 2013. |

| #3 | They should receive regular research ethics education, as do academia researchers at universities and national research institutes. |

| For regulator (e.g., Consumer Affairs Agency in Japan) | |

| #4 | Even if notification system is based on submitter’s own responsibility, it is necessary to confirm consistency with the protocol and obtain responses to any findings about differences or deficiencies. |

| For journal’s editor and peer-reviewer | |

| #5 | They should scrutinize the information based on registration and make a decision on publication. |

For regulators, even if they have notification systems, they should evaluate not only the formal confirmation in the article but also any differences from or deficiencies with the protocol. If they identify any problems, they should seek clarification from the submitter.

In regard to the journal’s editors and peer-reviewers, they should assess the consistency between registration and article contents before making decisions about publication. Prior studies indicate that these editors and reviewers often do not take advantage of the possibilities provided by registration [16,35,36,37]. For example, van Lent et al. reported that differences between trial information specified in registries and that reported in submitted manuscripts were not a decisive factor for manuscript rejection after initial editorial screening or after peer review [37]. As mentioned above, in food research, in addition to selective reporting, it is essential to check the content of interventions described in the protocol.

As a new tool for promoting registration and its effective operation, a blockchain solution using smart contracts has been proposed for managing data and process workflow in CTs [38]. This would be a working proof-of-concept solution to address the data management, protocol compliance, transparency, and data integrity challenges in a CT. In the future, CTR may move to such a comprehensive method.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nu14010081

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!