Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Health Care Sciences & Services

This case study illustrates how research can be effectively, although not maliciously, obstructed by the strict protection of employee medical data. Clearly communicated company policies should be developed for the sharing of workers’ records in the mining industry to improve HCPs.

- electronic data

- occupational exposures

- personal data

- audiometry

- healthcare providers

- machine learning systems

- ethical principles

1. Insightful Analysis

Worldwide, occupational hearing health research is impeded by data access restrictions, due to both legislation and guidelines that are designed to ensure the privacy and confidentiality of workers’ information and/or company-specific information. This case study illustrates how research can be effectively, although not maliciously, obstructed due to the over-zealous protection of employee medical data by a company. Specifically, access to (and therefore analysis of) the data of several thousand miners for research aimed at predicting occupational hearing loss was hindered by tensions between the application of ethical principles that govern workers’ medical data, such as ethical guidelines for good practice, confidentiality and the protection of personal information, and access to data for research purposes.

The use of machine learning systems to improve data quality and protect personal information has been legislated in South Africa [17,24], but data automation intended to guide medical decision still presents challenges. The participating mine used MS Excel and QMed to record miners’ data. According to Luy [35], MS Excel is inappropriate for the processing and analysis of large datasets as it lacks programming functions and falls short of the requirements for machine learning. On the other hand, the QMed system allows for big data risk assessment analysis and medical research [36]. Thus, using different MLSs with different capabilities impeded data access and restricted hearing health data analysis required in research. While this was a case study of a single large mine in South Africa, the findings are likely to apply to other mines and, perhaps, industries in this and other countries.

1.1. Justice

All miners undergo medical surveillance as a mandatory procedure to identify early signs of occupational diseases. The mines follow risk management protocols that are designed to efficiently monitor all miners and prevent occupational diseases [7,37]. Indeed, the mine in this case study conducted annual audiometry surveillance to identify miners at risk of developing ONIHL, and therefore to prevent ONIHL.

The South African mines are guided by acts (Mine Health and Safety Act No. 29 of 1996; PoPI Act of 2013) to ensure the aspect of justice, where miners have frequent and regular annual medical examinations to reduce occupation-related health risks and, in turn, benefit from best practice medical surveillance [34]. However, the use of different MLSs (rather than a single MLS), viz. Excel and QMed, in this case study, to capture annual audiometry medical surveillance records may hinder the accurate tracking of the miners’ hearing function, subsequent medical decisions, and research efforts related to hearing loss prevention.

Ethical challenge: Big data regarding hearing health medical conditions and treatment for tuberculosis and HIV from the QMed system could not be accessed, which prevented comprehensive data analysis for this case study and possibly restricted the mine’s implementation of actions for the early prediction and prevention of occupational hearing loss.

We recommend that this, and other mines store data in a single database, using one health management system to track the health of individual miners.

1.2. Beneficence

The mine HCP reports refer to audiometry surveillance big data records. The HCP reporting is based on occupational noise exposure levels, and hearing deterioration is calculated using a PLH score [38]. Other risk factors, such as tuberculosis and HIV treatments, and ear diseases such as otitis media, otitis externa, and impacted cerumen, were included in the QMed dataset (to which access was refused), but not in the records that were accessed for this study. Miners’ PLH scores can be influenced by these ear- and hearing-related risk factors (tuberculosis, HIV, otitis media, otitis externa, impacted cerumen, and their treatments) [22,23], which may not have been taken into consideration when assessing hearing deterioration and planning ONIHL prevention strategies. While the exclusion of miners’ medical information from the audiometry surveillance records may be based on maintaining the confidentiality of medical records and adhering to the mine’s privacy policies, it hinders efforts to prevent ONIHL [16,19,23].

The Mine Health and Safety Act (MHSA) has legislated the reporting of HCP data to the DMRE to ensure the accurate tracking of miners at risk of ONIHL, and the reporting of cases of ONIHL [34]. However, evidence-based research has shown that the South African mines use different HCP databases, which presents challenges such as missing records and the inconsistent recording of noise measurements and PLH scores [15,17]. The individual mines and the government departments that publish the annual occupational and medical reports should undertake quality assurance of the HCP reports submitted to the DMRE.

Ethical challenges: Incomplete records and inaccurately entered records lead to poor quality surveillance data, which in this case may lead to inequitable hearing healthcare for individual miners. This also has the potential to negatively affect the accurate prediction and prevention of occupational hearing loss.

It is recommended that companies develop and communicate transparent policies regarding big data access and sharing processes with all hearing conservation practitioners and miners, to empower miners to take ownership of their hearing health and to ensure equitable hearing health care and accurate monitoring of hearing health trends.

1.3. Confidentiality

The mine adhered to the rules that govern patient confidentially and protection of personal information with regard to occupational medical record keeping [24]. The National Health Act [26], Booklet 5 of the HPCSA [24], the MHSA [34], and the POPI Act [16] clearly state that healthcare professionals are mandated to record health data for all users (patients and/or employees) and to design electronic information systems to ensure the security of health records. By using MLSs for big data storage, the mine complied with these requirements.

The OMP is responsible for ensuring that the mine’s medical surveillance programs and MLSs are designed to monitor miners’ occupational hazards associated with health conditions, to evaluate intervention strategies used to mitigate risk, and to prevent occupational diseases [26]. Furthermore, the MHSA [34], the PoPI Act, and HPCSA [26] all require the application of privacy control measures for the protection of workers’ health records. For example, the mines are mandated to report occupational hazards and medical conditions affecting miners to the DMRE’s medical inspectors, and to ensure that miners’ identifiable information is anonymized [34]. In our assessment of the mine’s HCP records, there was a lack of clarity (in the mines’ annual health and safety reports) about which database(s) was used to report audiometry medical surveillance results to the DMRE, although confidentiality and protection of miners’ records were maintained [15,16]. The PoPI Act had not been effected when our study was conducted, but the mine’s medical officers applied the PoPI Act restrictions when denying our request to access the miners’ medical records for research purposes.

Ethical challenge: Criteria used in the decision to share miners’ confidential personal and medical records for medical research are provided in Booklet 5 of the HPCSA [26]. The application of the confidentiality rule is at the discretion of the mine’s medical officer (Section 3.2), but this was not clear to the OMP in this case study. Restricted access to records for miners’ medical conditions and treatments thereof may have been due to a misinterpretation /misunderstanding of Section 3.2 of Booklet 5 [26].

We recommend a transparent application of the privacy and confidentiality rules to all hearing conservation practitioners and employees who handle miners’ data, to encourage big data sharing. Moreover, we recommend that health care practitioners are knowledgeable about the legislation pertaining to confidentiality and their understanding thereof.

1.4. General Observations

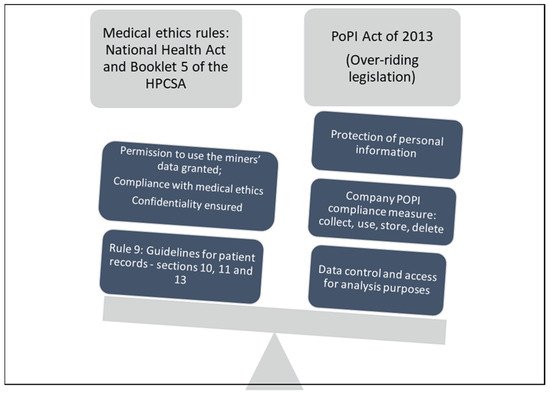

There are multiple ethical principles (Figure 3) for the protection of personal and medical information used by the mine’s hearing conservation practitioners for record keeping, reporting of ONIHL cases, and accessing data for research regarding ONIHL prediction and prevention. The PoPI Act [17] ‘carries more weight’ than the National Health Act and the HPCSA ethical guidelines [25,26,29]. Thus, the application of these ethical principles and data protection regulations shows respect for individual worker’s rights with regard to the protection of their medical information, which was ensured by the healthcare professionals (OMP and audiologist).

Figure 3. Illustration of medical ethics and personal protection regulations for access to personal data in MLSs (Protection of personal information (POPI).

Miners’ audiometry hearing results are reported in such a way that they are easy to understand. For example, results are relayed as ‘pass’ (hearing within normal limits) or ‘refer’ (hearing problem, which may require further intervention, e.g., refer to OMP or refer for a repeat hearing screening). However, research has indicated that miners have limited understanding and knowledge regarding their hearing function [39]. Thus, although the hearing screening results may be easily understood by the miners, the use of four separate datasets by hearing conservation practitioners may hinder the understanding of the negative effects of other diseases and ear-related conditions (and their treatments) on hearing function, by both the miners and the health practitioners. Miners should be encouraged to understand their hearing health status from the audiometry medical surveillance programs. To facilitate this, audiometry results should be integrated with medical records and presented to miners in an easy-to-understand manner.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijerph19010001

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!